Can Russian-US Scientific Cooperation Be Restored as Arctic Warming and the Ukraine War Intensify?

US and Russia have a long history of polar science cooperation.

The Arctic faces a climate emergency. The United States and Russia should be working together to understand the deepening crisis—a global security threat. Instead, essential cooperation is fractured.

Warming at a rate four times faster than the rest of the world, the Arctic is disproportionately affected by global warming: sea ice is diminishing, coastlines are eroding, ecosystems are collapsing, and there are existential risks to local communities and Indigenous livelihoods. The Arctic climate crisis is the “canary in the coal mine” for what awaits other regions. The transforming Arctic has direct consequences on warming and rising sea levels around the world.

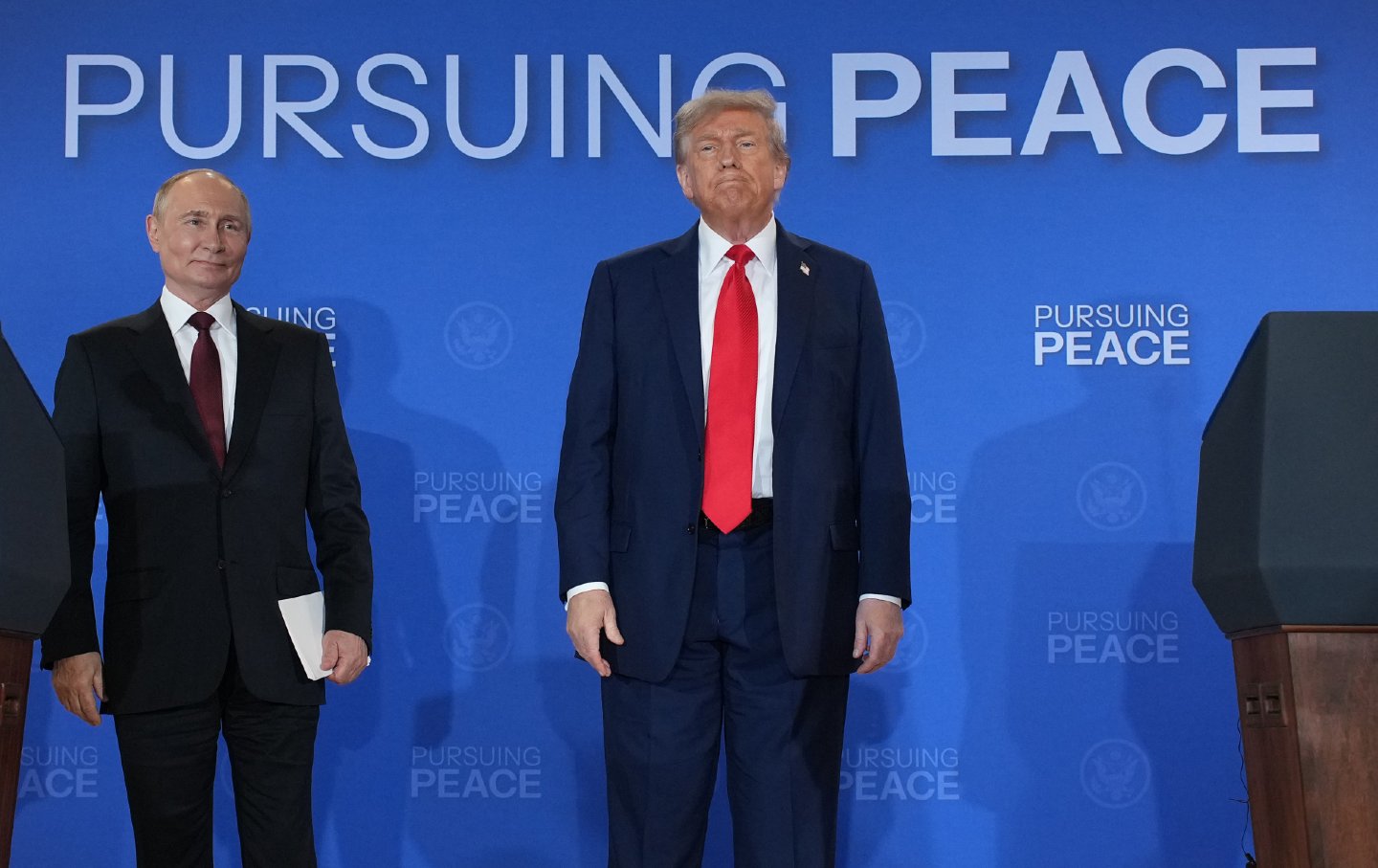

Meanwhile, scientific cooperation to understand these processes has been blunted since Vladimir Putin’s decision to send troops into Ukraine in 2022. Following the escalation of violence, joint projects, information sharing and expert working groups between Russian and Western researchers and institutes were severed.

Arctic cooperation has a nearly century-long history of successful initiatives based on mutual interest despite political differences between states. The sharing of data, international polar expeditions, and collaborative research are critical for constructing climate models and prognoses as well as informing effective adaptation and mitigation policies.

Arctic Council Pause

Now, this crucial research is jeopardized as international collaboration with Russia has been abandoned or terminated. In 2022, the Western Arctic states condemned Russia’s military actions in Ukraine and paused the work of the Arctic Council. The White House also announced a termination of scientific cooperation with Russia.

Russia had been the chair of the Council (2021–23) when the pause was announced. Russian Arctic officials called the pause “regrettable” and stressed the legacy of depoliticized dialogue.

Since its founding in 1996, the Arctic Council has been an exemplar of constructive post–Cold War diplomacy. Nominated for the Nobel Prize countless times, the Arctic Council is an intergovernmental forum for the eight Arctic states (Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden, and the US), Indigenous peoples’ representatives, non- governmental and international organizations, non-Arctic states, and experts to cooperate in understanding Arctic climate change, sustainable development, and environmental protection.

Since 2022, international scientists have lamented the dismal state of Arctic scientific cooperation. Russia comprises 53 percent of the Arctic coastline and over half of the Arctic human and wildlife population; excluding the Russian Arctic limits our collective knowledge on thawing permafrost, wildfires, polar bears and transforming ecosystems.

One geophysicist from the University of Alaska said that studying permafrost without Russian data is “like removing a couple of wheels from a car and trying to drive it home.” A 2024 research article found that the current exclusion of Russia from coordinated Arctic research has significantly deteriorated scientists’ ability to track and further predict the risks exposed by climate change.

The Indigenous peoples of the North, who have lived in the Arctic for millennia, likewise bemoan the gaps in scientific data and the welfare of their circumpolar families. Indigenous peoples were not consulted by the Arctic states prior to the pause. Previously, the Arctic Council was regarded as the only platform where Indigenous peoples have inclusion in decision-making at the global level.

Restoring Cooperation

Two years into the war in Ukraine, there are some headways in Russia-West Arctic cooperation. Norway took over the chair of the Arctic Council in 2023 and is gradually resuming work with Russia.

In February 2024, the council announced that official meetings of project and expert working groups will resume in a digital format. A month before, Norway’s chief Arctic official, Morten Høglund, met in person with the six Indigenous peoples’ organizations, including two representatives from Russia.

Norway’s relationship with Russia can serve as an example for dealing with Russia under the current political circumstances. In recent years, Norway has imposed sanctions against Russia, signed a bilateral defense agreement with the United States, and hosted NATO troops in the largest military exercise since the Cold War. At the same time, Norway continues collaboration with Russia to comanage fisheries in the Barents Sea, the Norwegian-Russian border, and Coast Guard rescue operations.

Similarly, the United States maintains some channels of cooperation with Russia in the Arctic, especially in the Bering Strait. The US and Russian Coast Guards maintain lines of communication to protect people and marine resources on both sides of the strait. While joint exercises have been on hold, the US and Russian Coast Guards still commit to the enduring agreements on search-and-rescue and emergency operations. Cooperation continues even against the background of provocative Russian naval exercises off the coast of Alaska.

Moreover, there is collaboration at the individual and informal levels. Some academic conferences in the US and Russia, where scientists share research on Arctic natural and social sciences, still involve Russian and American researchers. Such developments demonstrate that while relations may have been mostly severed, there are still narrow openings for cooperation around issues that are seen as essential.

Lessons from History

Despite the stark challenges of reigniting full-fledged cooperation today, the United States and Russia have a long history of polar science cooperation and diplomacy over common interests during times of geopolitical confrontation.

During the Cold War, American and Russian researchers engaged in numerous scientific exchanges and joined dozens of countries to study sea ice, aurora borealis and polar meteorology as part of the 1957–58 International Geophysical Year. In the 1970s, the US and USSR signed landmark agreements on environmental protection and polar bear conservation.

At the end of the Cold War, the cooperation between Soviet and Western Arctic scientists built interstate trust and spilled over into the political and military spheres. In a famous 1987 speech in northern Russia, Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev recognized that “the community and interrelationship of the interests of our entire world is felt in the Arctic, perhaps more than anywhere else,” and that “scientific exploration of the Arctic is of immense importance for the whole of mankind.” Gorbachev’s ruminations went on to inspire the 1996 formation of the Arctic Council.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →After the Cold War, US-Russia Arctic cooperation skyrocketed as Western researchers poured into the previously inaccessible Russian Arctic. Notable collaborations include the Russian-American Long-term Census of the Arctic (RUSALCA, which means “mermaid” in Russian). Across several expeditions to the Bering and Chukchi Seas between 2004 and 2015, Russian and American scientists jointly studied marine chemistry, glaciology, oceanography, and ecosystems.

RUSALCA existed “as a miracle,” according to its participants, because of initial opposition from Russian and American security services. The project continued against the background of political tensions related to the 2008 Russo-Georgian War and 2014 Ukraine crisis. Such examples offer practical examples for common-interest cooperation despite steep political disagreements.

Today, climate science has fallen victim to the diplomatic fallout of the war in Ukraine. Nonetheless, there remains significant and ongoing support from international scientists and Arctic residents for Moscow and Washington to find a common understanding in studying and tackling the Arctic climate crisis.

Scientific cooperation, an essential endeavor for the world’s survival, can help build trust between the United States and Russia, and prevent a conflict in a region that has not seen interstate violence since World War II.

Take a stand against Trump and support The Nation!

In this moment of crisis, we need a unified, progressive opposition to Donald Trump.

We’re starting to see one take shape in the streets and at ballot boxes across the country: from New York City mayoral candidate Zohran Mamdani’s campaign focused on affordability, to communities protecting their neighbors from ICE, to the senators opposing arms shipments to Israel.

The Democratic Party has an urgent choice to make: Will it embrace a politics that is principled and popular, or will it continue to insist on losing elections with the out-of-touch elites and consultants that got us here?

At The Nation, we know which side we’re on. Every day, we make the case for a more democratic and equal world by championing progressive leaders, lifting up movements fighting for justice, and exposing the oligarchs and corporations profiting at the expense of us all. Our independent journalism informs and empowers progressives across the country and helps bring this politics to new readers ready to join the fight.

We need your help to continue this work. Will you donate to support The Nation’s independent journalism? Every contribution goes to our award-winning reporting, analysis, and commentary.

Thank you for helping us take on Trump and build the just society we know is possible.

Sincerely,

Bhaskar Sunkara

President, The Nation