EDITOR’S NOTE: This article was produced in collaboration with +972 Magazine and Local Call, two media outlets run by Palestinian and Israeli journalists. It is one of a pair of pieces exploring what the erasure of the Green Line separating Israel from the occupied Palestinian territories means for the future of the land between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea. You can read its complement, "Palestinian Resistance Tore Down the Green Line Long Ago," at this link.

TEL AVIV, ISRAEL-PALESTINE—More than a year after a wave of violence, rage, and resistance swept through the land between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea, the events of May 2021 are still very much present in the minds of Israeli Jews and Palestinians. Two hundred and eighty-six Palestinians, most of them in Gaza, and 13 Israelis were killed during the 11 most intense days, but it was not only the number of casualties that left a mark. It was also the fact that the drama unfolded all over historical Palestine: in Jerusalem, in Gaza, in the West Bank, and most important, in Israel’s “mixed cities” such as Lydd, Ramle, Acre, and elsewhere, which was almost unprecedented since 1948.

As one would expect, Palestinians and Israeli Jews have nearly diametrically opposed views on these events, including their causes and the lessons to be learned from them. Yet in one regard there is a peculiar consensus: The conflagrations that broke out across the country revealed that the Green Line—the demarcation drawn after the 1948 war that many hoped would serve as a border between Israel and a future Palestinian state—is no longer relevant.

For many Palestinians, this was a cause for pride. The Palestinians, commentators argued, had managed to overcome the divisions Israel imposed on them and protest simultaneously all over “historical Palestine”—in Lydd and Ramle inside “sovereign” Israel, as well as in occupied East Jerusalem, the West Bank, and Gaza. The uprising was dubbed the Unity Intifada.

For many Israelis, meanwhile, especially those on the right, the protests reaffirmed their conviction that the problem is not Israel’s occupation of the West Bank or its siege of Gaza but rather the Palestinians’ refusal to accept a Jewish presence in any form in “historical Israel.” Much like the Palestinians, they saw the land between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea torn apart by violence even as it was more unified than ever as a single political unit.

It could be argued that the erasure of the Green Line is an inevitable and perhaps even positive development, as the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is, first and foremost, about the war of 1948 and the Nakba—the expulsion and prevention of return of hundreds of thousands of Palestinians—with the occupation of the West Bank and Gaza in 1967 following from that. And yet, inevitable or not, this new moment certainly represents an important shift. The collapse of the Green Line, and no less important the collapse of the ability to imagine it, has set a new stage in the decades-long conflict.

The Green Line was never meant to be Israel’s permanent border with its neighbors. It came about as a result of the armistice agreements signed by Israel, Jordan, Egypt, and other Arab states after the 1948 war. The armistice line was marked on the map with a green pencil (hence the name Green Line), and it was never accepted as an international boundary. In fact, it was only the outbreak of the 1967 war that turned it into a widely accepted border, as all United Nations declarations—beginning with Resolution 242 in November of that year—demanded that Israel withdraw to its borders before that war, meaning to the Green Line.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

It was also at this moment, precisely as the line became official, that Israel’s relationship to it began to shift. To understand how this process began, one must go back to the discussions held by the Israeli government during and right after the 1967 war.

On June 15, five days after the fighting ended, Yigal Allon, who commanded the pre-state Palmach Zionist paramilitary group and later served as a minister in the Israeli government, put forward a plan for the territories seized by Israel. This plan called on the government to immediately annex the newly occupied Jordan Valley (a 15-kilometer-wide strip west of the Jordan River), the city of Jericho, and the Old City of Jerusalem, leaving the Palestinians floating in an “autonomous region” in the remainder of the West Bank.

Moshe Dayan, the charismatic Israeli defense minister who was widely viewed as the architect of the war, supported Allon’s proposal to turn the Jordan River into Israel’s eastern border but had reservations about Palestinian autonomy. “I propose that the regime in the West Bank be a military government,” he said, noting that he did not want to “take any step that will drag us into a situation where [Palestinians] can be elected to the Knesset.” He had his way, and by the end of July, the Israeli lira was recognized as an official currency on both sides of the line and Palestinians were granted permission to work inside Israel. With the annexation East Jerusalem a few weeks after the war, followed by the establishment of settlements in the Jordan Valley and Kiryat Arba near Hebron, the erasure of the Green Line had begun.

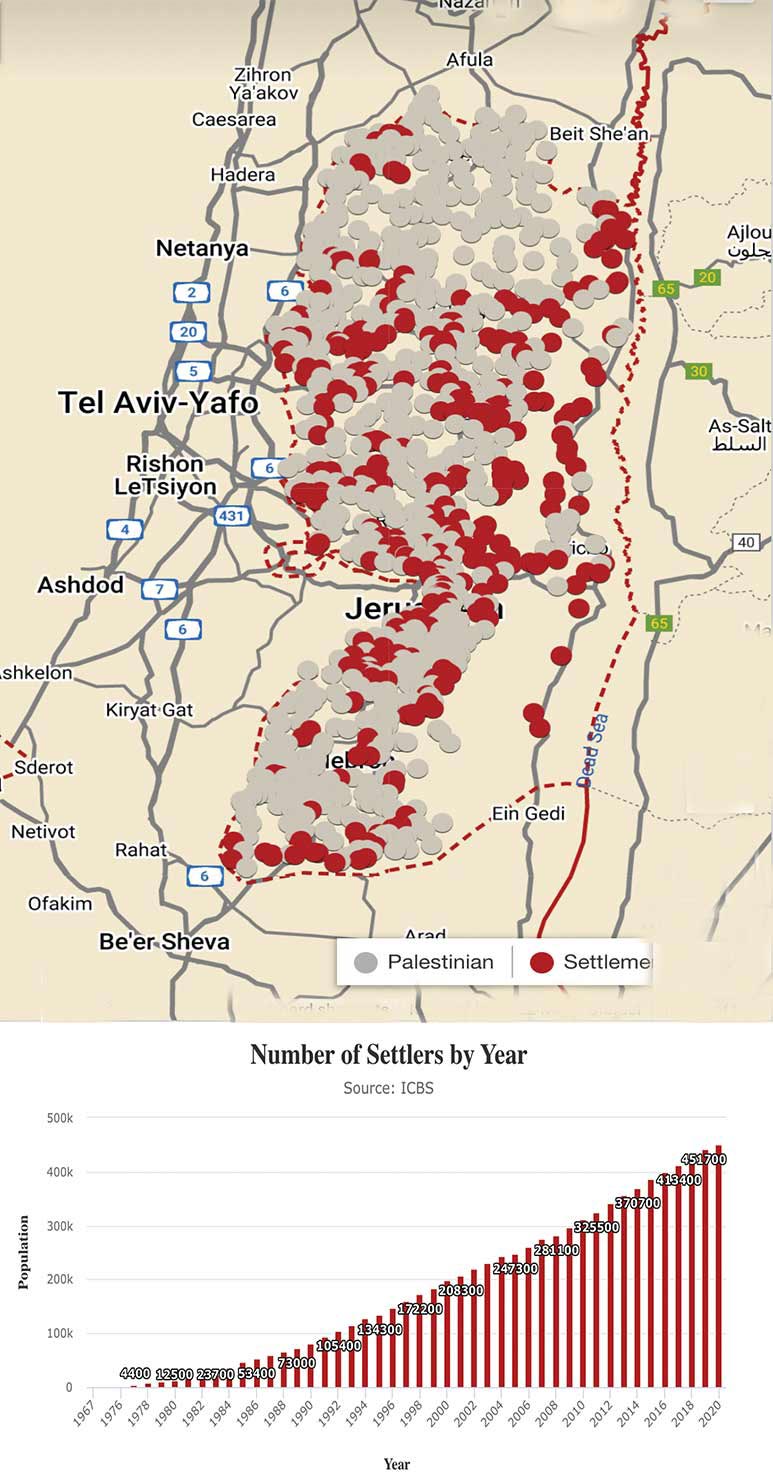

Over the next two decades, successive Israeli governments would continue in this vein, slowly chipping away at both the idea and the reality of the Green Line. After Menachem Begin was elected prime minister in 1977 on a platform of establishing a “Greater Israel”—one stretching from the river to the sea—he set in motion the project of building settlements in the West Bank. (When Begin assumed office, the number of settlers was 1,900; by 1987, the number had grown to almost 50,000.) Yet he refrained from formally annexing the West Bank and Gaza, preferring instead to keep the Palestinians living there under military rule. This limbo served Israel well, allowing it to continue occupying the territory without giving Palestinians political rights.

The First Intifada in 1987 showed Israeli Jews what it meant to force millions of people to live under military occupation. With the signing of the 1993 Oslo accords—which led to the creation of the Palestinian Authority in parts of the West Bank and were supposed to lead to the establishment of a Palestinian state on the other side of Israel’s pre-1967 borders—the idea of the Green Line made its comeback in the Israeli political arena. It served the interests of Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and the Jewish center to try to convince the Israeli public that separation—Israelis here, Palestinians there—was the only solution to the conflict.

With the violence of the Second Intifada and the collapse of the Camp David talks in 2000, Israel imbued the Green Line with yet another meaning. It became a wall, a concrete and metal barrier called the Separation Wall by Israel and the Apartheid Wall by Palestinians and human rights activists. Rather than conceiving of it as a political border to solve the conflict, Israelis understood it as a line of defense against the Palestinian suicide bombing attacks of the time—a tool for proving that separation from the Palestinians is possible, even without a political agreement. (Israel’s “disengagement” from Gaza in 2005 only reinforced this concept.) But that wasn’t all that the newly concrete border did. Because the wall was not built along the Green Line but, in many places, ran deep into the West Bank, surrounding Palestinian villages and bifurcating Palestinian lands, it also pushed the Israeli presence deeper into the occupied territories.

When Benjamin Netanyahu returned to power in 2009, he sought to undo key parts of this paradigm. In fact, the central legacy of his second tenure as prime minister, from 2009 to 2021, can be summarized as an effort to “re-erase” the Green Line—for Israelis if not for Palestinians, who, in critical ways, were locked behind an ever more restrictive set of legal and physical barriers. He did this through two main policies: expanding settlements in the West Bank and legitimizing them internally among Israeli Jews as well as on the international stage; and, due to his vehement opposition to a Palestinian state, replacing the Oslo peace process with what he termed “economic peace” with the Palestinians. Economic peace, in Netanyahu’s eyes, meant that Israel would lift restrictions on Palestinian economic development and allow Palestinians to work in Israel in greater numbers, while the Palestinians would give up their political demands, such as an end to the occupation and the settlement enterprise.

The settlements did expand during Netanyahu’s time. According to the Israeli NGO Peace Now, which tracks settlement growth in the occupied territories, there were some 296,000 settlers in the West Bank in 2008, just before Netanyahu returned to power; by 2021, that number had grown to 415,000. And these numbers represent an undercount, since Peace Now does not include the Israelis living in East Jerusalem.

Yet numbers are not enough to understand just how far Netanyahu went to render the reality on the ground irreversible. Yesh Din, an Israeli human rights organization, compiled a list of 60 bills pertaining to various forms of annexation of the West Bank that were proposed from 2015 to 2019; eight were signed into law. The most prominent among them was the Expropriation Law, passed in 2017, which retroactively authorized Israeli settlement outposts on privately owned Palestinian land in the West Bank. It was later struck down by Israel’s High Court, but it signaled Netanyahu’s intentions: to completely blur the divide between sovereign Israel and the West Bank and to normalize the settlements and settlers.

These moves did not go unnoticed by Palestinians and Israel’s human rights community. “Steps towards de-jure annexation are evident through legal opinions and shifts in the State’s position (such as in petitions adjudicated in Israeli courts and publications issued by the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs), as well as in legislation,” Yesh Din wrote in a 2019 report. “These shifts ostensibly challenge the West Bank’s legal status as occupied territory, Israel’s authority to operate there, and Israel’s duty to protect the rights and property of the Palestinian population living under its occupation.”

This process was not restricted to legal and legislative actions but was enabled by an increasingly potent political force in Israel. Despite its relatively small size—no more than 10 percent of the population—the religious Zionist community, which is the main force behind the settler movement, is overrepresented in various branches of the Israeli security forces and judiciary as well as in the realm of public opinion. According to one study, the percentage of graduates of the Israel Defense Forces’ field officer training course who came from the religious Zionist schooling system grew from 2.5 percent to 34.8 percent between 1990 and 2018. Three of the 15 justices on Israel’s High Court come from this community, and two of them actually live in West Bank settlements. One recently wrote the court’s decision to green-light the expulsion of more than 1,000 Palestinians from their homes in Masafer Yatta in the South Hebron Hills.

“There is a large-scale involvement of religious [people] in promoting the occupation and legitimizing it,” wrote Mikhael Manekin, a well-known Israeli leftist, in Haaretz last year. Manekin, himself an Orthodox Jew who recently published a book about religious Zionism, wrote that “the representatives of Religious Zionism, a leading force in the army, would ‘make kosher’ any action by the IDF…. It seems that those wearing a kippa are leading the ideology of ethnic supremacy.”

The religious community’s growing and outsize power has paid off: The political campaign, led mainly by settlers, in support of the annexation of parts or all of the West Bank grew stronger during the fourth Netanyahu government, from 2015 to 2019, and in 2017, the Likud Central Committee passed a motion to annex the West Bank. A week before the April 2019 elections, Netanyahu promised to annex the Jordan Valley, the first Israeli prime minister to do so since 1967.

When Donald Trump presented his “deal of the century” in 2020, the hearts and minds of the broader Israeli public were ready. With the exception of the liberal Meretz Party, every Jewish political party in the Knesset supported the plan, which called for the annexation of all Israeli settlements in the West Bank, leaving the Palestinian territories as Bantustan-like enclaves. Trump was also the first foreign leader to recognize Israel’s annexation of East Jerusalem, and he moved the US Embassy to the contested Israeli capital. With its support for his plan, the majority of the Jewish Israeli public affirmed the death of the Green Line.

The story of Netanyahu’s plan for “economic peace” is somewhat muddier: It neither greatly improved the Palestinian economy nor ushered in an era of peace, but it did increase the interdependence of the Israeli and Palestinian economies. This was especially evident after the outbreak of Covid-19 in 2020. For decades, Israel forbade Palestinian workers from staying overnight in Israel because of what it deemed “security reasons.” Yet as the country went into lockdown and the Palestinian Authority severely restricted movement inside the West Bank and from the West Bank into Israel, Israel forced some 30,000 Palestinian workers to remain for weeks inside Israel, preventing them from going back to their homes, because they were badly needed in the construction and agriculture sectors.

Quoting Palestinian sources, Local Call (the news site I work for) reported in 2020 that Israel even opened intentional breaches in the separation barrier to let in Palestinian workers. It is estimated that until the most recent wave of violence, in April and May of 2022, some 40,000 to 80,000 Palestinians were passing through these breaches daily to work in Israel, even though they did not receive permits from the Israeli authorities. They joined the 120,000 Palestinians who have permits from the army to work in Israel. If we add to them the more than 100,000 Jerusalemite Palestinians who work, buy, or travel in Israel, we see that at least 260,000 Palestinians—perhaps many more—cross the Green Line every day from the occupied territories, including East Jerusalem.

At the same time, hundreds of thousands of settlers regularly cross the separation barrier. This seems routine to most Israelis, but it is clear that it is impossible to create a true barrier between Israel and the West Bank given such a reality. In this sense, the separation wall has lost most of its symbolic meaning for Jewish Israelis. Although the majority of them were convinced, and probably remain so, that the barrier prevents suicide bombings and other forms of violence by Palestinians, anyone who knows the situation on the ground can tell you that the main function of the barrier is psychological: It is there to mark a boundary in the Israeli Jewish consciousness more than to serve as a real physical obstacle. If one remembers that potentially tens of thousands of Palestinian citizens of Israel cross the barrier into the West Bank every week for shopping, leisure, studying, or living in Palestinian cities and villages, one begins to understand that separation does not truly exist and that the Green Line has, in practice, been erased.

This reality dawned on many Jewish Israelis in may 2021, when, after Israel attempted to evict Palestinians from their homes in the East Jerusalem neighborhood of Sheikh Jarrah, Hamas fired rockets from Gaza and protests and violence erupted in other Israeli “mixed cities” and in the West Bank. The illusion that some Green Line, fence, or barrier separates Jews from Palestinians collapsed to a large extent.

Evidence of this new understanding was on display during the most recent wave of violence, which began in March 2022 with the deadly attack in Be’er Sheva by a Palestinian citizen of Israel, a follower of the Islamic State, and continued with the attacks in Tel Aviv, Bnei Brak, and other Israeli cities. Some of the Palestinian attackers were Israeli citizens; others traveled easily from the West Bank to Israel through breaches in the separation barrier. Never has it been so evident that there is no real dividing line between Israel and the West Bank, between Jews and Palestinians.

This reality was manifested in the Israeli response to the attacks in the past two months. On the one hand, Israel carried out deadly military operations in the West Bank, mostly around Jenin Refugee Camp, killing dozens of Palestinians (more than 60 have been killed since the beginning of the year), as well as the Palestinian American journalist Shireen Abu Akleh, in the futile hope that the operations would prevent future attacks. The government and the army also pledged to mend the breaches in the separation barrier and replace parts of the fence with a concrete wall. On the other hand, Defense Minister Benny Gantz has promised to increase the number of entry permits granted to Palestinian laborers not only in the West Bank but also in Gaza, and the Israeli authorities have approved 4,000 new units for settlers in the West Bank. It is as if Israel is saying, “Let’s rebuild the Green Line and destroy it at the same time.”

Before Prime Minister Naftali Bennett resigned in June, his government had intensified this contradiction. Bennett had agreed to take annexation off the table in a mutual understanding with his partners from the center-left, but he had also refused to meet with Palestinians and declared that there would be no Palestinian state under his watch. While it becomes ever more evident to many Israelis that the separation of Jews and Palestinians is impossible, there is no political will to grant equal political rights to the Palestinians in the West Bank and Jerusalem—to say nothing of those living under siege in Gaza.

This tag-team attempt by Netanyahu, Bennett, and the current prime minister, Yair Lapid, to bury the two-state solution while refusing to offer equal rights to Palestinians under a single regime is likely what prompted local and international human rights groups and the United Nations’ special rapporteur on the occupied territories to recognize what Palestinians have been saying for a very long time: that Israel commits the crime of apartheid.

While many on the Israeli center-left continue to hope that separation is still possible, the right wing understands that the abolition of the Green Line may lead Palestinians to escalate their demands for equal rights and the democratization of the land between the river and the sea. Wedded to the idea of Jewish supremacy, the right views this possibility as a direct threat and thus is intensifying its propaganda against the Palestinian citizens of Israel while trying to goad the Israeli army into expanding its violence against Palestinians in the West Bank, even going so far as to raise the prospect of a new Nakba.

In many ways, the present deadlock—no Green Line yet no formal annexation—works for Israel; but in others, it only serves to increase Israeli frustration. With the dismantling of the Green Line, Israel has effectively swallowed up the Palestinians, yet it continues to be dismayed when it sees how they refuse to give up their national identity and their struggle for freedom and return. This explains, at least in part, the attacks by Israeli officers on the pallbearers at Abu Akleh’s funeral: The simple act by Palestinians of raising their flag and manifesting their identity was conceived as a threat to the public order.

The fact that the Green Line has ceased to function as a physical or even an imaginary barrier between Israel and the West Bank does not necessarily imply that the two-state solution is dead and that we are moving toward a one-state solution—or toward a dramatic rise in violence that may indeed culminate in Israel carrying out a new Nakba. Jewish Israeli society is still distinct from Palestinian society, and the desire for self-determination and an independent Palestinian state is still very strong among Israelis and Palestinians.

During his recent visit to Israel, the occupied Palestinian territories, and Saudi Arabia, US President Joe Biden reiterated his “commitment” to the idea of two states based on the 1967 borders—meaning the Green Line. Even Lapid said that he still supports this idea for the sake of a “democratic and Jewish” Israel. For his part, Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas has warned that time might be running out for a two-state solution, but he said that it is still on the table. If Lapid is reelected in November, it is not impossible that some sort of negotiations between Israelis and Palestinians could resume after being frozen for more than a decade. These may seem like empty words, considering the facts on the ground, but words do count.

What all this means is that the two-state idea in its traditional incarnation is indeed in deep crisis but not dead. What is needed now is not to give up on the Green Line but to reimagine it in a form that is far less rigid than the one envisaged by the architects of Oslo. I am part of an Israeli-Palestinian movement, A Land for All, that is calling for two independent states, Israel and Palestine, with a “soft” border between them that will run along the Green Line, allowing for freedom of movement and residence for all, Jews and Palestinians, including refugees. According to this vision, the two states will join in a confederation or union, not unlike the EU model, and Jerusalem would be an open city, the capital of both states, governed by joint rule.

Others, like former Israeli politician Yossi Beilin and Palestinian lawyer Hiba Husseini, both veterans of past negotiation efforts, offer a different model of confederation. The revival of the idea of a single democratic or binational state is also part of an effort to respond to the practical erasure of the Green Line, and there could be other ideas. But one thing is certain: After 55 years of occupation, and more than a decade of intensive efforts to replace it with annexation, it is hard to deny that the Green Line does not represent the same physical and emotional reality that it did many years ago.

This is not necessarily negative. To some extent, since 1967, the Green Line has been an illusion. Palestinians and Israelis live on and fight over the whole of the land between the river and the sea, with most of them seeing the whole of it as their homeland. The conflict did not begin in 1967, as the concept of the Green Line may suggest, but long before it. The Green Line promoted the idea of separation, of hostility, the assumption that Jews and Palestinians cannot live with one another. When we—particularly my fellow Israeli Jews—fully understand that we have to share this land, our political imagination will open up. The Green Line closed it shut.