September 11, 1973, Was a Warning: Democracy Can Die in a Day

Fifty years ago, the US exported a cult of revanchist violence to Chile. Now it has made its return.

Soldiers outside a government building in Santiago, Chile, on September 12, 1973, a day after the coup against President Salvador Allende’s democratically elected socialist government.

(AP Photo)Given the weight of sadness of September 11, it’s jarring to remember how innocent I was when I first encountered the date in a political setting. I was living in Chile as a study-abroad student. It was 1995, and as I walked the streets of Santiago, still a political novice, I saw that date, 11 de Septiembre, on a street sign and did not understand why an avenue would bear that name. The codirector of my study-abroad program was a Chilean journalist who explained to me that September 11, 1973, was when hell was unleashed on anyone in Chile who thought they could peacefully and electorally create a better world.

Three years after the election of Socialist Party President Salvador Allende in 1970, the military overthrew him. The codirector of my program told me that Gen. Augusto Pinochet’s shock troops had brutalized him. They broke his back, literally and politically, during a “questioning.” Pinochet secured his power through massacres, torture, and a climate of fear. And a street in 1995 paid tribute to the atrocities committed in the name of “saving” the country from democratic socialism.

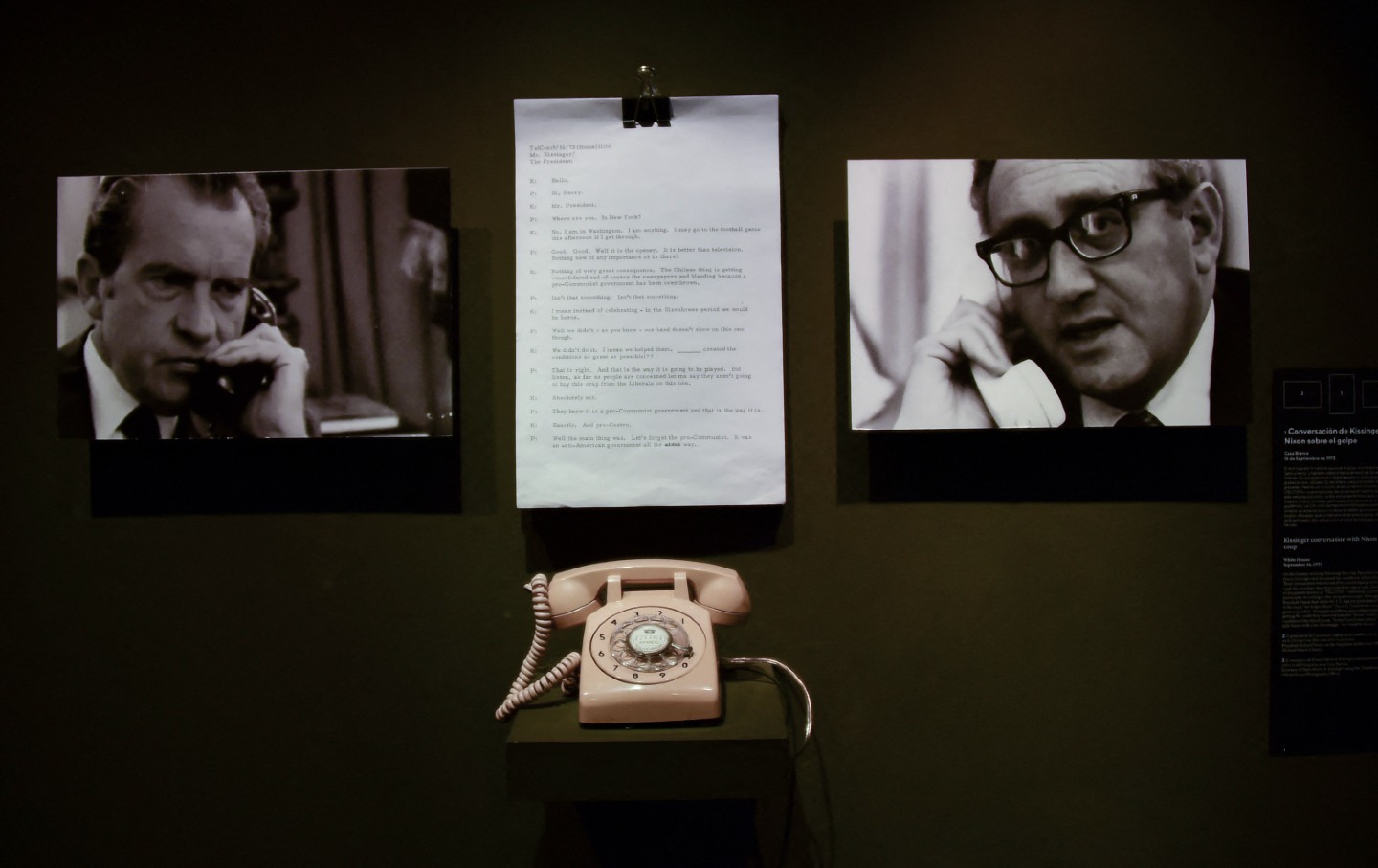

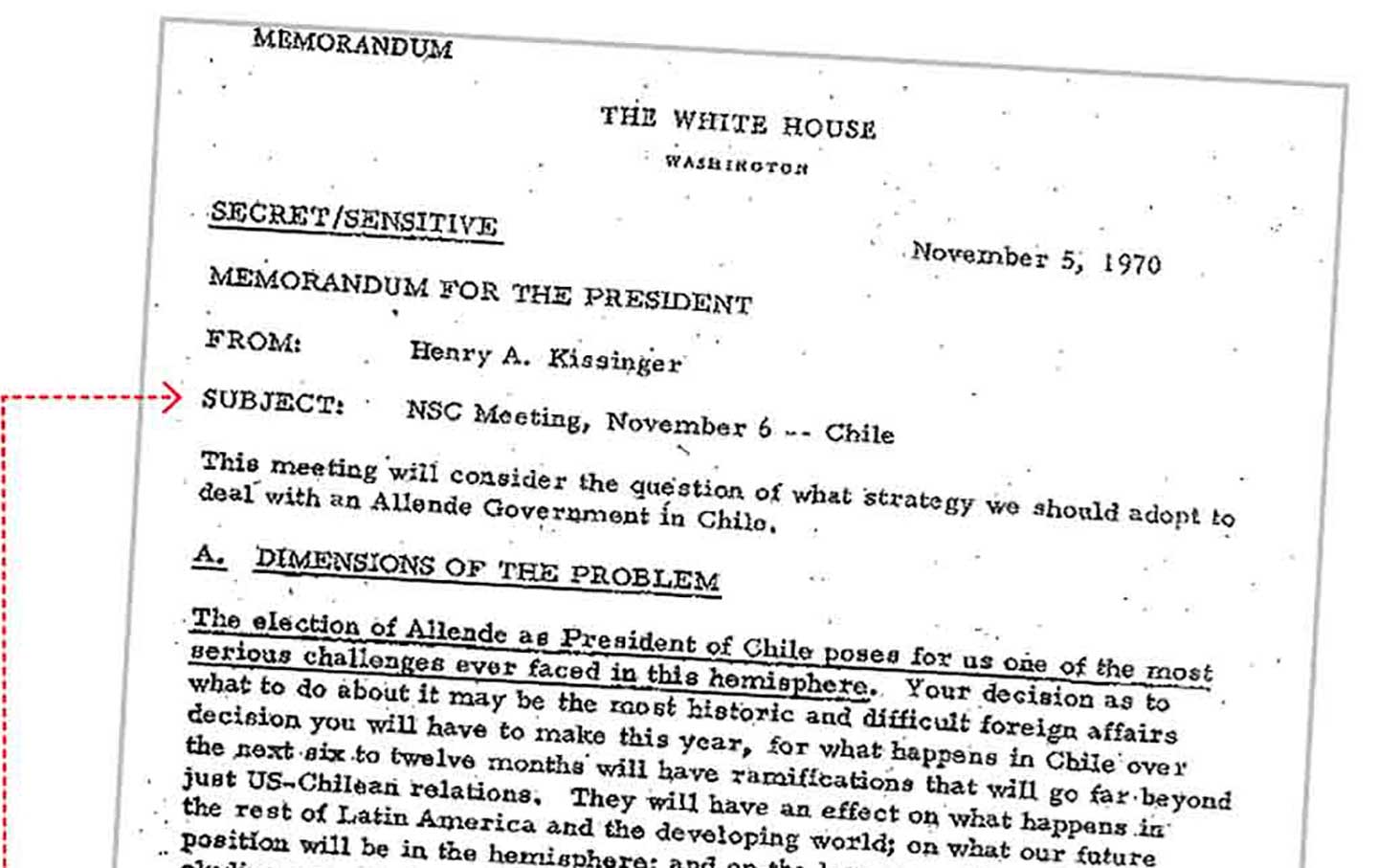

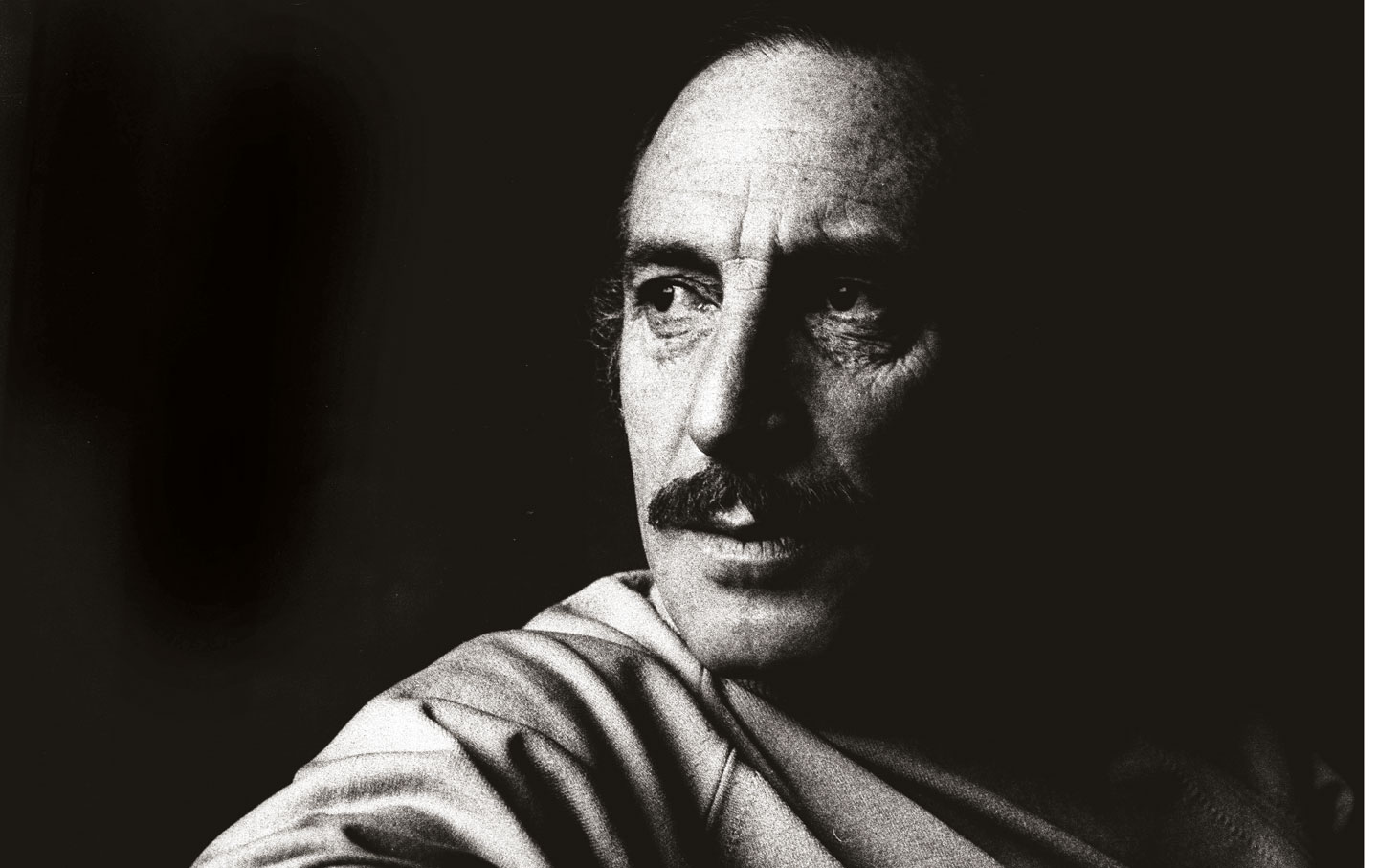

I learned as much as I could about the Chilean September 11 that year—and was sickened. The more I found out about the thousands of people killed and so many more thousands exiled or tortured in a country of 12 million people, the more horrified I became. I learned of the folk singer Victor Jara, whose hands were mutilated before his public execution. As my program’s codirector told me, Jara was more than just the Bob Dylan of Chile. I remember that conversation so clearly because it was the first time I learned about the US involvement in the military coup. I learned about their years of support for the murderous Pinochet. And I learned about Los Hijos de Chicago—the Chicago Boys, the right-wing University of Chicago economic students under the auspices of Milton Friedman who guided the economic shock therapy that gutted Allende’s progressive reforms. It finally made sense to me why, when I told people I was a college student in the United States, I was often asked with wariness, “Do you study in Chicago?”

September 11 nearly eradicated a generation of Chilean fighters. The goal was to exterminate or exile all of them. No one was safe, or perhaps more importantly to the police state, no one felt safe. Fast-forward 50 years, and Pinochet is a hero in far-right circles in the United States. At right-wing rallies, reactionaries don T-shirts lauding Pinochet and his ways of dealing with workers and the left. We exported this cult of revanchist violence to Chile 50 years ago, and now it has made its return.

I remember after September 11, 2001, amid the shock, heartache, and rage, several gutsy Chilean journalists decided to take that moment to write about their September 11 and the state terror that has been historically exported by the United States that looked to be returning home. They were almost universally excoriated for drawing parallels between the attacks on the World Trade Center and their country’s anguish. The political leaders of the United States decided that this would not be a day of reflection over foreign policy and shared agony. 9/11 would be ours and ours alone—especially when it needed to be leveraged to move a country toward war. Perhaps these journalists should’ve been heeded and heard instead of slandered and dismissed.

September 11 is not only a day of commemoration; it’s a warning. The children of Pinochet are in organizations like the Proud Boys and Moms for Liberty. If we don’t organize against these currents, it will betray an incredible naïveté. There are lessons from Chile. And they are staring us in the face.