How Germany Silenced Its Artists to Support Israel

As Israel intensified its genocide in Gaza, Germany ramped up its long-simmering war on dissent, silencing Palestine solidarity while bolstering its own far right.

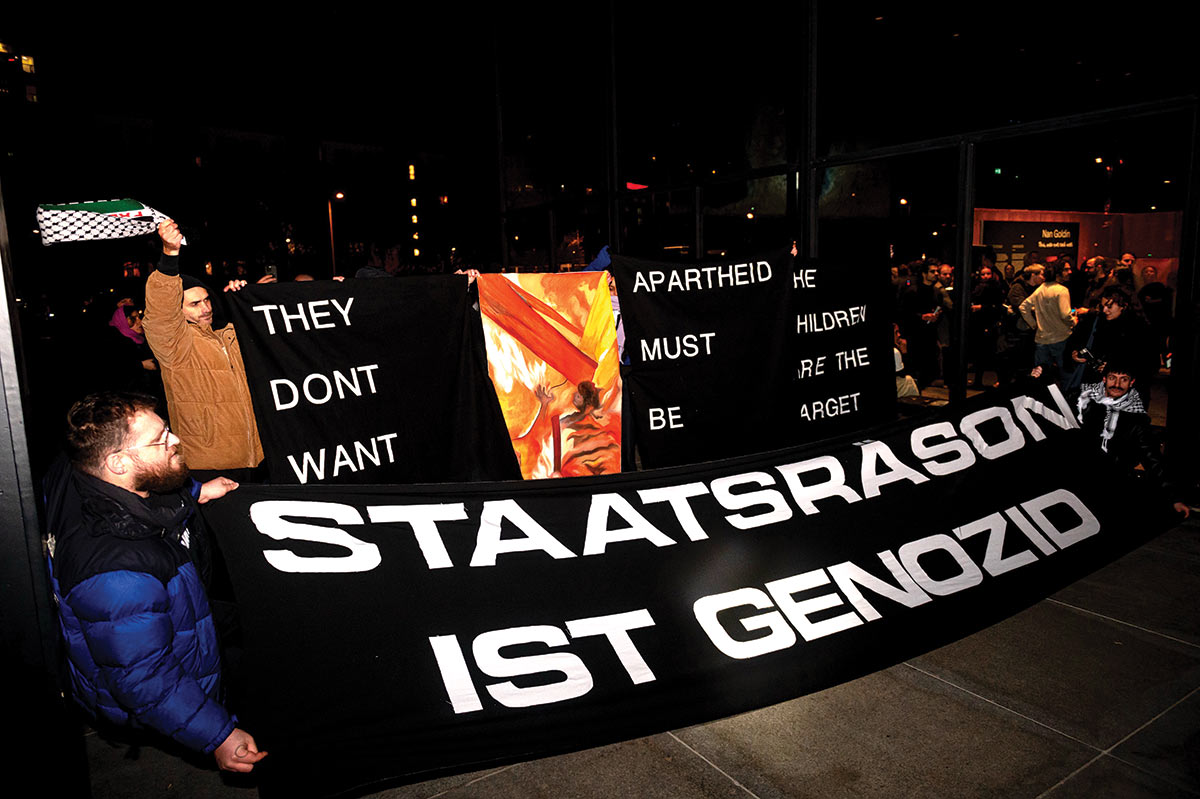

A year ago, Nan Goldin returned to Berlin to rebuke the German government and its cultural apparatchiks. “This is a city that we used to consider a refuge,” the artist announced from a small stage at the Neue Nationalgalerie. It was the opening night of her career retrospective, ominously titled “This Will Not End Well.”

When Goldin first visited in the 1980s, the divided city-state served as an appropriately gritty backdrop for her photos of friends and lovers—a European satellite for the creative demimonde of New York’s East Village. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, she lived there for two years via an artists’ residency program, part of a vast federal and state network for cultural funding. Back then, Berlin was “one big underground,” she later recalled. “Everything was extreme.”

Goldin was far from the only international artist to make Berlin home. By the early years of the millennium, artists from all over the world were flocking to the German capital, attracted by generous support for a gamut of arts and culture outside the mainstream, as well as cheap rent and abundant studio space. Local officials quickly latched on to this flourishing scene as a means of reinvention, envisioning Berlin as a new artistic capital for Europe. Even as it cleaned up and real estate prices skyrocketed, Berlin kept its rough edges, retaining a reputation for adventurous experimentalism and outspoken critical discourse.

That freedom now appears to have reached its limits. “Tongues have been tied,” Goldin declared at the exhibition opening, “gagged by the government, the police, and the cultural crackdown.”

Goldin was referring to the country’s aggressive response to support for Palestine, especially since Hamas’s attacks on Israel on October 7, 2023, and the start of Israel’s ongoing genocide in Gaza. This repression, although nationwide, has been largely concentrated in Berlin. “Over 180 artists, writers, and teachers have been canceled since October 7,” Goldin continued. “Many of them Palestinian, 20 percent of them Jews.”

A small, somber figure in black with a shock of red curls, Goldin read from a podium, her gravelly voice shaking slightly. But her intonation was steady, lending a gravitas that the swells and dips of a more expressive orator might have lacked. “I decided to use this exhibition as a platform to amplify my position of moral outrage at the genocide in Gaza and Lebanon. If an artist in my position is allowed to express their political stance without being canceled, I hope I’m paving a path for other artists to speak out without being censored.”

“Anti-Zionism has nothing to do with antisemitism,” Goldin’s statement was met with sustained cheers. When she turned to leave the stage, the audience erupted: Palestinian flags unfurled amid chants of “Viva, viva, Palestina!” In that ecstatic moment, it felt as if the artist had pulled out a stopper and released all the pent-up grief and passion of a suppressed movement.

Then, the moment was over. Goldin’s celebrity status in the art world, and her renown as an activist, enabled her exhibition to move forward when so many other shows were withdrawn, and entitled her to speak when so many other artists were silenced. Goldin was, in effect, too big to cancel. Nevertheless, in the days that followed, German media and cultural officials excoriated her words as “tasteless,” “oblivious,” and the “most shameful moment in the 56-year history of the Neue Nationalgalerie.” Six months later, in an interview with Der Spiegel, the museum’s federally appointed director was still brooding over that “horror night.”

This summer, images of mass starvation in Gaza began to disturb the composure of German politicians; Chancellor Friedrich Merz announced that he would limit arms shipments to Israel. Speech in galleries and auditoriums became slightly more open. But the damage is done. The ethnic cleansing of Palestine continues, and its reverberations have been used to break and remake Berlin. In this story of cultural repression, we can also see the reorganization of society and the rise of a new far right. But we would do well to remember how it started: enforced by the liberal center and acceded to by the very people in a position to push back rather than roll over. It is also a familiar story.

German officials across the political spectrum like to frame their suppression of Palestinian solidarity in positive terms: They describe their motive as the “protection of Jewish life,” to quote one of the many government resolutions that have been passed at the federal, state, and municipal levels in recent years; and they present their actions as an extension of national responsibility in the aftermath of the Holocaust. Never mind that numerous progressive Jews have been caught in their dragnet. In reality, Germany has learned to weaponize antisemitism, perversely exploiting its own dark history in a deeply cynical twist.

This turn of events shouldn’t come as a surprise to a US audience, by now wearily accustomed to an ever-widening crusade of “anti-antisemitism” that has less and less to do with actual Jews. Although long simmering, it boiled over in the immediate weeks after October 7, when a flurry of open letters demanded a ceasefire. In the US art world, where two decades of such petitions (Arts for Afghanistan! Art Workers for Black Lives!) had gone unnoticed by anyone other than their signatories, the swift and ruthless reaction came as a nasty surprise: redlined events and blacklisted artists, hasty firings and conscientious resignations. That tumult was quickly subdued, however, even as more determined protests expanded on college campuses across the country.

The extreme response in both arenas in the United States was initiated by some of the country’s wealthiest citizens—among them Jewish arts patrons and college donors—as well as the leaders of those bastions of liberal thought, university presidents. In the name of fighting antisemitism, they sought to crush criticism of Israel—and ultimately leftist dissent altogether. The assault on progressive advances began here in the private sector and the political center, before the cudgel was handed over to the tyranny of the Trump regime to accomplish the real work of gutting equal-rights protections. Now Trump is returning his attention to culture, demanding its “alignment” with his white-nationalist vision—or, to use the original German, Gleichschaltung.

In Germany, however, this crackdown was instigated by the government, the primary funder of the country’s museums, theaters, orchestras, and other cultural institutions. The arts are widely considered a public good and a necessity for a democratic society, receiving federal support as well as grants from regional and local administrations. Ironically, the state proudly proclaims that its investment in culture safeguards artistic freedom—a freedom that is enshrined in the country’s postwar Constitution, the Grundgesetz (“basic law”).

What it really means is more complicated. “Cultural activity is like an extension of the state,” explains Ana Teixeira Pinto, a Portuguese cultural theorist who moved to Berlin in 2006. As such, it bumps up against another core tenet of the German state: “Anything that is publicly funded cannot deviate too much from the Staatsräson.”

Although Staatsräson is now a familiar rallying cry among German politicians, it’s worth retelling the tangled history of this hybrid byword. The concept took its place in the national political discourse four decades after the end of World War II, when West Germany was only beginning to reckon with its Nazi past. In an oft-cited article from 1985, the Green Party politician Joschka Fischer held that the “essence” of the West German reason of state was “responsibility for Auschwitz.” In sharp contrast to the 16th-century philosophy of raison d’état—which argued that the state’s interests superseded those of its people and overrode any ethical principles—this modern formulation sought to marry national objectives with moral ones.

The Staatsräson became more than just a governing dictate; it was an obligation passed on to all German citizens by way of Erinnerungskultur, or “memory culture”—in education, historical preservation, and the erection of new monuments and museums. After 1990, memory culture became a fundamental building block of a national identity shared by West and East, simultaneously serving to reassure Europe that a reunified Germany posed no threat. Around the turn of the millennium, however, Staatsräson began to be delinked from memory culture. It became tethered instead to the state of Israel.

This reorientation didn’t emerge out of nowhere. For decades, Israel had pressured other nations to, essentially, prioritize the survival of the “Jewish state” over the safety of their own Jewish citizens. As Antony Lerman details in Whatever Happened to Antisemitism? (2002), Israeli officials and pro-Israel groups argued that the “classic” hatred of Jews was taking a novel form: hatred of Israel. In actuality, international condemnation of Israel’s brutal occupation was increasing, and this support for Palestinian solidarity movements was steadily rising. Israel sought to reframe political opposition as a “new antisemitism.”

After 9/11, this contention found a more receptive audience. With the end of the Cold War, the West was looking to cast a new villain in its long-running franchise of civilizational clash. The “War on Terror” pumped up fears of Islamic fundamentalism and cemented the geopolitical importance of the “only democracy in the Middle East.” As Europe and the United States closed ranks around Israel, the European Union was roped into the effort. In 2005, the European Monitoring Centre on Racism and Xenophobia (EUMC) posted a new “working definition” of antisemitism on its website. Two sentences define antisemitism as prejudice against Jews, followed by 11 “contemporary examples.” Seven relate to Israel, such as “denying the Jewish people their right to self-determination” and “comparing contemporary Israeli policy to that of the Nazis.”

Despite attracting immediate controversy—after all, Jewish opposition to the Zionist project dates as far back as Zionism itself—the expanded text reached Israel’s target audience: Western officials. Three years later, in 2008, Chancellor Angela Merkel addressed the Israeli Knesset. In a twist on the usual axiom, Merkel described Germany’s Staatsräson not in historical terms but as a present-continuous commitment… to Israel.

This reconceptualization has stuck, repeatedly reiterated in official discourse and declarations. Five days after Hamas’s attack, Chancellor Olaf Scholz spoke before the Bundestag to assert, “Die Sicherheit Israels ist deutsche Staatsräson”: Israel’s security is Germany’s reason of state.

As in the 1990s, the new Staatsräson began to reshape domestic policy. A major step occurred in 2015, when Israel declared the decade-old, Palestinian-led Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) movement a “strategic threat”—applying a term previously used for armed opposition groups to a nonviolent campaign of disengagement. Israeli officials started lobbying lawmakers in other countries to take legislative action against BDS as well as to codify the “new antisemitism.” The EUMC no longer existed, but in May 2016, its definition was appropriated and assiduously promoted by the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA), a diplomatic one-hit wonder known solely for this cover. Whereas the EUMC took pains to describe its examples of antisemitic sentiment as conditional, cautioning that any interpretation of intent must consider the “overall context,” under the IHRA they became viewed as determinate. Now endorsed by 46 countries (and counting) in Europe, Asia, and the Americas—in addition to hundreds of local governments, corporations, and universities—the IHRA working definition of antisemitism is definitely working for Israel. As Lerman underlined when we spoke recently, “It was a political act.”

A few months later, the center-right Christian Democratic Union (CDU)—the party of Merkel, who was then facing a backlash for her “open doors” immigration policy, accepting more than a million Middle Eastern refugees into the country—passed a motion condemning BDS. Following the Israeli government’s own line, already made “official” via the Staatsräson and the IHRA, the CDU described anti-Zionism as simply a 21st-century disguise for antisemitism. Similar declarations followed from other political parties and local legislatures across the country, before reaching the parliamentary level in May 2019. In its resolution, the Bundestag called on the federal government to deny financial support “to any organizations that question Israel’s right to exist…or to projects that call for a boycott of Israel.”

Initially, the resolution appeared to have little application to the arts. After all, German cultural organizations didn’t generally hold a public stance on Israel, and it was unlikely that any artistic project promoted a boycott. However, a series of high-profile cancellations soon made clear that government officials were eagerly overreaching—applying the resolution’s interdiction to any individual who had ever expressed a similar political opinion. Among the first targets were a British Pakistani author, a Lebanese American artist, the Jewish director of the Jewish Museum in Berlin, and a Cameroonian postcolonial theorist. Soon, this expanding mesh of extralegal rules and regulations would come to severely circumscribe the public sphere.

Cultural leaders decided to push back. The heads of 32 state-funded museums, theaters, and other arts organizations joined together to form the Initiative GG 5.3 Weltoffenheit; the name refers to the paragraph in the Grundgesetz that guarantees artistic and academic freedom and to its promise of “open-mindedness.” In December 2020, the group circulated a plea for the importance of free debate and dissent. The statement made sure to emphasize that the cosigners personally disavowed BDS, even while they rejected a “counter-boycott” of its supporters. The directors of some of Germany’s most prominent institutions held a press conference to take questions, then fanned out across the media, participating in interviews and encouraging further discussion.

Their resolve was shockingly short-lived. When politicians and journalists predictably accused the group of antisemitism, threatening their organizations with retaliatory funding cuts, the united front quickly fell. Susan Neiman, the director of the Einstein Forum in Potsdam and a participant, recalled the rapid fallout: “There was a lack of courage, a lot of people got cold feet, and it fizzled out.” The Weltoffenheit initiative dissolved, at least in any public form. Another observer snidely commented to me, “It turned into a WhatsApp group.”

Despite the speedy capitulation of the cultural sphere, the effects of the 2019 anti-BDS resolution remained relatively muted for a while. “When I moved here in 2020, I never encountered any hostility,” recollected Basma al-Sharif, a Palestinian artist who lives in Berlin. Much of al-Sharif’s work over the past 20 years, both video and installation, meditates on Palestine and the dislocations of diasporic experience. “I had already shown in Berlin quite a bit, and it felt really comfortable,” she noted. “People were encouraging me to speak; they were asking for honest conversation about Palestine and the occupation. There was nothing that I was ever told was off-limits.”

Al-Sharif heard about the resolution and some of the early controversies, but she greeted them with a shrug. “I’m not new to this—I grew up mostly in the US,” she said. “I’m very familiar with false claims of antisemitism when criticizing Israel, and how not to validate such attacks in the first place.” She figured that Berlin would be similar.

And for a few years, it was. Al-Sharif’s films continued to be screened in Germany. In 2022, she and her husband, the Egyptian German artist Philip Rizk, were awarded a two-year fellowship with the Berliner Programm Künstlerische Forschung (Berlin Artistic Research Program). That year, a scandal erupted at Documenta, arguably the world’s most prestigious art exhibition and a landmark of German cultural funding since 1955. One of the works on display in Kassel contained a Jewish caricature, leading to furious debates over the artists, the curators, and the future of Documenta itself.

“And then October 7 happened,” al-Sharif said, “and all of that changed—dramatically changed, very quickly.” A cascade of cancellations and “postponements,” never rescheduled, soon followed throughout the country. Much like the first wave that began in 2019, these abrupt terminations primarily affected Palestinians and other Arabs, Muslims, Jews, and people of color.

Out on the streets, tens of thousands protested Israel’s savage bombing campaign in Gaza; inside cultural spaces, support for Palestine was hushed. The reasons for axing events were no longer restricted to support for BDS or even criticism of Israel. The president of the Frankfurt Book Fair declared his desire “to give Israeli and Jewish voices additional time” as he scrapped an award ceremony for a Palestinian novelist. A Berlin gallery stated that it wouldn’t exhibit a “one-sided presentation of Muslim life without a corresponding counterpoint” when it dropped a photography show by a German artist of Turkish descent. Needless to say, this demand that “both sides” get equal exposure did not hold true for events with an Israeli focus.

Also new were the people initiating the cancellations: not government officials but the directors of cultural institutions themselves—no matter how radical or antiestablishment the institution’s reputation. The Volksbühne, Berlin’s famously leftist “people’s theater,” disinvited the former UK Labour Party leader (and noted critic of Israel) Jeremy Corbyn from a conference organized by the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. The multilevel, poly-darkroom queer club Berghain pulled an appearance by the keffiyeh-clad DJ Arabian Panther. (Before you scoff, Berlin’s techno scene has been recognized as “intangible cultural heritage” by UNESCO, and clubs receive state support too.)

For every well-publicized cancellation, countless artists were simply no longer considered. In al-Sharif’s case, she said, “There wasn’t anything concrete—I wasn’t removed from any shows or screenings.” Rather, “people I’d been working with, artists and curators, suddenly distanced themselves or just didn’t contact me anymore.” The daily slaughter in Gaza was an inescapable nightmare for the artist, but in place of compassion and commiseration, she encountered a wall of silence. Well over a year later, al-Sharif remained incredulous: “I just thought it would be human to talk about what’s going on.”

When I asked the Beauftragte der Bundesregierung für Kultur und Medien (Federal Ministry of Culture and Media, or BKM) for comment at the end of last year, I received the following statement: “It’s not the role of the Minister of Culture and the Media to define the limits of freedom of art or freedom of speech. She has always been very clear that within the limits of the constitution and the law, it’s the institutions’ own responsibility to navigate the space between freedom of art and their stand against antisemitism, racism, and other forms of group-focused enmity.”

However, I slowly heard a more complicated story through the curatorial grapevine. After October 7, the culture minister at the time, Claudia Roth, and her secretary general, Andreas Görgen, convened a series of meetings with the leaders of cultural institutions that receive federal support. Over the course of a few months, gatherings took place virtually over Zoom or in person at Haus der Kulturen der Welt (House of World Cultures, or HKW) in Berlin. According to a museum staffer who sat through some of the Zoom calls, the officials “basically laid out the terms” for arts programming going forward. The staffer summarized their understanding of those terms, expressed via a laborious double negative, reflecting the BKM’s own cautious language: “Publicly funded institutions cannot be seen as not supporting Israel.”

An invitation for a meeting at HKW dated December 12, 2023, presented this pro-Israel logic in a less contorted manner. The culture minister opened by describing October 7 as “the darkest day in Israeli history and in postwar Jewish history.” Looking back at the two months since this act of “terror against Jews,” Roth said nothing of the bunker-busting bombs that Israel was dropping on Gaza nor of the Palestinian children who had already been killed; she noted only that Germany had experienced “a frightening outbreak of antisemitism,” asserting: “Culture cannot ignore this.”

The BKM’s meetings were attended primarily by directors, who were left to communicate the message to their staffs. A Berlin-based curator described this trickle-down effect, as colleagues across institutions discussed the various restrictions they’d been given (and how to work around them). One worry was about presenting Palestinian or pro-Palestinian voices “without them being ‘corrected’ by the other side,” as the curator put it. This apprehension would seem to explain the cancellations at the Frankfurt Book Fair and the Berlin gallery, as well as the Neue Nationalgalerie’s decision to organize a symposium for the day after Goldin’s opening featuring speakers with state-aligned views; the artist pithily referred to the event as a “prophylactic.” Roth herself had complained that Goldin’s speech was “unbearably one-sided.”

Both Roth and Görgen were replaced at the BKM after the new CDU government took power earlier this year. When asked about the meetings, Görgen provided a curious non sequitur in response: “Leftist politics is about fighting against the alienation from humanity. The terrorist attack by Hamas denied the humanity of its victims, driven by an antisemitic ideology. Any denial of human dignity stands in direct opposition to a humanist leftist politics. That line must be drawn—and during my time in office, I did my best to do so.” (Roth could not be reached for comment.)

Regardless, it should be noted that before joining the BKM, Görgen acted as an adviser to the Weltoffenheit group; Roth, for her part, was one of 16 members of the Bundestag who signed a statement against the 2019 anti-BDS resolution. As a result, both had been accused of antisemitism by pro-Israel politicians and press and conservative Jewish groups—castigations that continued even as the pro-Palestinian scene complained of being squeezed. This same dynamic existed on the local level in Berlin and throughout Germany. Facing criticism from both left and right, cultural officials tried to chart a middle course. Whether this can be ascribed to an attempt at political self-preservation or to nebulous personal convictions, the results pleased almost no one. The curator said, flatly, “I realized for the first time in my life what it must be like to work under an authoritarian regime.”

And yet, everyone I spoke with agreed that much of the pressure was implicit. “There wasn’t always someone actually censoring things,” the curator explained. “It was the climate—the BKM, the media, the politicians.” A director who attended a January meeting at HKW concurred: “So much was between the lines, insinuated.” They also learned by example. “We would see someone punished for using words like ‘genocide’ or ‘apartheid,’” the curator said, “so it was clear we should avoid using them.”

Whatever it was, it worked. A few outspoken cultural workers were quietly pushed out, for reasons never clearly stated, but “basically, the whole field was submissive enough to avoid it,” the curator said. “It’s a disciplinary regime in the Foucauldian sense.” Indeed, months later, almost everyone I contacted declined to discuss the subject, even off the record.

“I think what’s really going on,” surmised Susan Neiman of the Einstein Forum, “is incredible intimidation, but also just self-censorship.” Born and raised in the United States, Neiman wrote an admiring book about German memory culture six years ago, but she has described the current atmosphere as “hysteria.” As she sees it, “This is such a deep matter of German guilt.” An artist I spoke with offered another interpretation, based on a different stereotyped national behavior: “In German, there’s a saying, ‘vorauseilender Gehorsam.’ So before you get the order, you already do what you think will come.” The museum staffer echoed this in translation: “There is a lot of obeying in advance.”

While some state-funded spaces have pushed the perceived boundaries of what is allowed, none have been braver than a young cultural center in Neukölln, Berlin’s most ethnically diverse neighborhood. Founded in 2020 by three QT/BIPOC women, Oyoun describes itself as “a home for queer*feminist, migrant, and decolonial perspectives”—a bustling hub that made the most of its state-owned four-story building, filling it with collectively curated festivals, community-led events, workshops for artists and activists, interdisciplinary exhibitions and research groups, international studio residencies, and a range of children’s programming. The arts space received €1 million a year from the Berlin Senate, and funding was slated to extend through 2025.

That is, until Oyoun refused to accommodate state censorship. In September 2023, city officials objected to an upcoming anniversary celebration for the activist group Jewish Voice for a Just Peace in the Middle East (also known by its abbreviated German name, Jüdische Stimme), which was to be held at Oyoun in November. If the venue hosted Jüdische Stimme, officials said, it wouldn’t be a “safe space” for Jews. “That’s an extremely problematic statement for the government to make,” Louna Sbou, Oyoun’s cofounder and artistic director, told me. “It implies that certain Jews should be protected and certain Jews should not.”

After October 7, pro-Palestinian protests occurred across the city; in Neukölln, home to a significant Arab population, these were violently suppressed by police in riot gear. Jüdische Stimme reconceived its November celebration as a shiva—a traditional Jewish mourning ritual—for both the Israeli and Palestinian dead. But the Senate continued to demand the event’s cancellation, and the fight spilled over into the press as politicians escalated their accusations. A Neukölln MP insisted to Tagesspiegel that antisemitic incidents had taken place at Oyoun; the Neukölln mayor boasted to Der Spiegel that he’d wanted to defund the arts space for years; Berlin’s culture senator promised to “review” its funding. But Oyoun didn’t bow to the intimidation, and Jüdische Stimme’s gathering took place as planned.

Two weeks later, at a livestreamed meeting of the Berlin Senate, the culture senator once again emphasized his dedication to stamping out “any form” of antisemitism in the arts. “And when I say ‘any form,’” he reiterated, “I also mean any hidden form of antisemitism.” With those nonsensical words, he announced that Oyoun’s funding would expire at the end of the year—two years early.

Sbou and her team fought back. They hired a lawyer and sent cease-and-desist letters to those libeling them. They went to court for an injunction against Tagesspiegel and won. The Berlin Senate’s own internal investigation found no proof of antisemitism at Oyoun, forcing officials to invent a new claim to halt funding: the thinnest excuse of “changed priorities.” But, Sbou noted, “the Senate still publicly describes us as antisemitic, as if it’s the real reason for defunding us.” Despite Oyoun’s efforts to rally support, prominent cultural organizations—more mainstream, more white—stayed silent.

After a year-long legal battle, Oyoun was evicted at the end of 2024. A lawsuit to regain state funding is expected to take years. When I met Sbou in March, it was Ramadan and she was fasting. She seemed subdued, unsure whether Oyoun could continue to cover its lawyers’ fees. When we spoke again a few months later, she was in Morocco visiting her mother, who had moved back after three decades in Germany. Sbou sounded brighter, more determined. With the help of private grants, she said, Oyoun would be hosting a week-long residency in Marrakech for artists and cultural workers based in Germany: “It’s a signal to the community that we remain resilient and continue to resist.”

Shortly before Oyoun’s eviction, the Bundestag passed another resolution, titled “Never Again Is Now—Protecting, Preserving, and Strengthening Jewish Life in Germany.” It is a disturbing document that, in some 1,700 words, fully instrumentalizes the country’s Jewish citizens in order to accelerate state repression: “Their existence is an enrichment of our society and, in view of our history, a special declaration of trust in our democracy and our constitutional state.” The text then makes very clear how this “trust” will be repaid: by expanding the funding restrictions of the 2019 anti-BDS resolution to include a broad prohibition against “spreading antisemitism”—as defined by the IHRA, natürlich. Only one area of activity in Germany is recommended for extra oversight: “art and culture.”

The weaponization of antisemitism against Israel’s detractors is nothing new—it’s a long-standing strategy to silence recrimination and evade responsibility. One Israeli government after another has placed the nation’s survival over the safety of Jews. In Germany, it’s easy to see how the shift to defending Israel serves German interests on multiple levels. In his 2024 book The Message, Ta-Nehisi Coates writes that the founding of Israel after the Holocaust was widely seen as “not just the curving arc of justice but something more: a perfect circle. Not merely a righting but a restoration, a redemption.” The existence of Israel is also the key to Germany’s redemption, the “perfect circle” that allows it to move on from backward-facing guilt to forward-marching righteousness. To criticize Israel as unjust—let alone to question the very concept of a Jewish state—is tantamount to questioning Germany’s absolution.

This is not a minor irony. When antisemitism is redefined as antipathy to Israel rather than to Jews, the German far right—which admires Israel’s ethno-nationalism—is no longer the primary culprit. Instead, suspicion falls on recent immigrants, especially Arabs and Muslims who have no connection to the Holocaust but have very good reasons for criticizing Israel.

Significantly, however, it’s not the far-right party, Alternative für Deutschland, that first made this argument. In 2017, the CDU mayor of Frankfurt contributed a guest article to a local magazine in which he claimed, “Today’s antisemitism rarely wears the familiar jackboots”; rather, it’s “imported into Europe” from the “cultures of the Near and Middle East.” One month later, the AfD won enough votes to be seated in the Bundestag.

The following year, Germany established the office of the Federal Commissioner for Jewish Life in Germany and the Fight Against Antisemitism; states, regional governments, schools, and police departments soon appointed their own antisemitism officers, and the Frankfurt mayor himself was named to the post in the state of Hesse. (As many commentators have pointed out, the government’s sole Jewish antisemitism officer converted to Judaism after he got the job.) Yet “imported antisemitism” remained the focus, even as statistics and studies consistently show that antisemitic incidents have increased over the past decade because of neo-Nazi extremism, not immigration. In 2021, more than 80 percent of all antisemitic crimes in Germany were committed by far-right adherents.

Why is the CDU excusing the AfD rather than pinning this violence on them, especially as the party’s support continues to rise? Politicians continue to denounce the AfD while simultaneously falling all over themselves to copy-paste its nationalist, anti-immigrant positions. Early this year, a CDU member made this explicit in a blunt statement on her official social media account: “You don’t have to vote AfD for what you want. There is a democratic alternative: the CDU.” The CDU triumphed in the February federal election, and Merz was named chancellor—but the AfD doubled its vote share from four years ago, surging to second place.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s embrace of the far right didn’t prompt Germany’s political mainstream to reconsider its blind support for Israel. Nor has the genocide triggered a new reinterpretation of Staatsräson. In fact, since October 7, Staatsräson has been invoked by the German government to deny citizenship to applicants who question Israel’s right to exist; to bar a British Palestinian surgeon from speaking publicly about Gaza (where he volunteered with Doctors Without Borders); and to deport four residents who participated in pro-Palestinian protests. Staatsräson has even appeared in the reasoning for judicial decisions.

“Never again is now,” the Bundestag proclaimed. In Germany, however, “never again” doesn’t mean “never again for anyone.” Only Jews are separated out for special treatment—over other marginalized populations such as Muslims, people of color, and immigrants. At the same time, Jews are once again scapegoated, held up as the pretext for the state’s racism, censorship, brutal suppression of protests, and deportation of its undesirables. Fascism repeats itself: first as antisemitism, then as anti-antisemitism.

This year, the Berlin Senate drastically cut cultural funding. “Changed priorities” are seen at the federal level as well. Germany, like many countries shifting from neoliberalism to the right, no longer feels the need to invest in culture—especially when it’s an incubator of leftist ideas. “The art world is the center of a counter-discourse that’s no longer welcome,” said Teixeira Pinto. “And because it’s publicly funded, the state can destroy it.” She continued, “In order to turn Berlin into a proper ‘German’ city, the government had to clamp down on the arts sector. Now that Berlin has been gentrified, it doesn’t need artists anymore.”

In May, Merz’s newly appointed culture minister took over. In his first comments to the press, Wolfram Weimer stated that “the skewed relationship of the BKM to the Jewish community will be restored and a conflicted chapter of German cultural policy will come to an end.” A month later, he was railing against the left’s “assault on freedom” and the “radical-feminist, postcolonial, eco-socialist culture of indignation.”

The dividing line of possibility in Berlin today might be between forums that are dependent on public money and those that are not. Consider the Spore Initiative, supported by an independent funder, where two group exhibitions related to Palestine are currently on view; in July, Spore hosted the first annual conference of the Association of Palestinian and Jewish Academics. On a smaller scale are semicommercial ventures like the concert venue KM28 and Hopscotch bookstore, which hold talks alongside performances and readings. The freedom and openness with which Berlin has been associated for so many decades now finds itself dependent on the private sector.

Given the events of the past year, it’s clear that Goldin’s speech didn’t accomplish what she hoped it would. But to al-Sharif, that night still meant a great deal. “There could not have been a more important official space in Germany for her to make that speech,” al-Sharif said. She brought along her young son. “We walked into a space where our allies outnumbered those who were clueless. We were looking at a sea of people—not just Palestinians, not just Arabs—who were shouting the things that we’ve been shouting for decades.”

When I saw al-Sharif in July, she was in the final stages of editing a new film. Morgenkreis (Morning Circle) follows an Arab immigrant and his son through parallel processes of integration—via the state and early education. “I feel there’s a strong homogenizing force in German culture that is super-xenophobic, and it starts really early, in childhood,” al-Sharif explained. “Even here in Berlin, it’s extreme.” That’s how Goldin described the city in the 1990s: “Everything was extreme.” The question is to what extent Berlin’s creative, countercultural, far-out extreme can survive the other extreme—Germany’s swerve to the far right.

Support independent journalism that does not fall in line

Even before February 28, the reasons for Donald Trump’s imploding approval rating were abundantly clear: untrammeled corruption and personal enrichment to the tune of billions of dollars during an affordability crisis, a foreign policy guided only by his own derelict sense of morality, and the deployment of a murderous campaign of occupation, detention, and deportation on American streets.

Now an undeclared, unauthorized, unpopular, and unconstitutional war of aggression against Iran has spread like wildfire through the region and into Europe. A new “forever war”—with an ever-increasing likelihood of American troops on the ground—may very well be upon us.

As we’ve seen over and over, this administration uses lies, misdirection, and attempts to flood the zone to justify its abuses of power at home and abroad. Just as Trump, Marco Rubio, and Pete Hegseth offer erratic and contradictory rationales for the attacks on Iran, the administration is also spreading the lie that the upcoming midterm elections are under threat from noncitizens on voter rolls. When these lies go unchecked, they become the basis for further authoritarian encroachment and war.

In these dark times, independent journalism is uniquely able to uncover the falsehoods that threaten our republic—and civilians around the world—and shine a bright light on the truth.

The Nation’s experienced team of writers, editors, and fact-checkers understands the scale of what we’re up against and the urgency with which we have to act. That’s why we’re publishing critical reporting and analysis of the war on Iran, ICE violence at home, new forms of voter suppression emerging in the courts, and much more.

But this journalism is possible only with your support.

This March, The Nation needs to raise $50,000 to ensure that we have the resources for reporting and analysis that sets the record straight and empowers people of conscience to organize. Will you donate today?