A Catalog of Gaza’s Loss

Recording what has been erased—and making sense of what remains.

This piece is part of A Day for Gaza, an initiative in which The Nation has turned over its website exclusively to voices from the Gaza Strip. You can find all of the work in the series here.

Aquestion has been haunting me for some time now, a question whose answer I hope is not already lost. It is less a neat inquiry than a muffled cry inside each of us, rising over and over against days filled with repeated loss: Who are we?

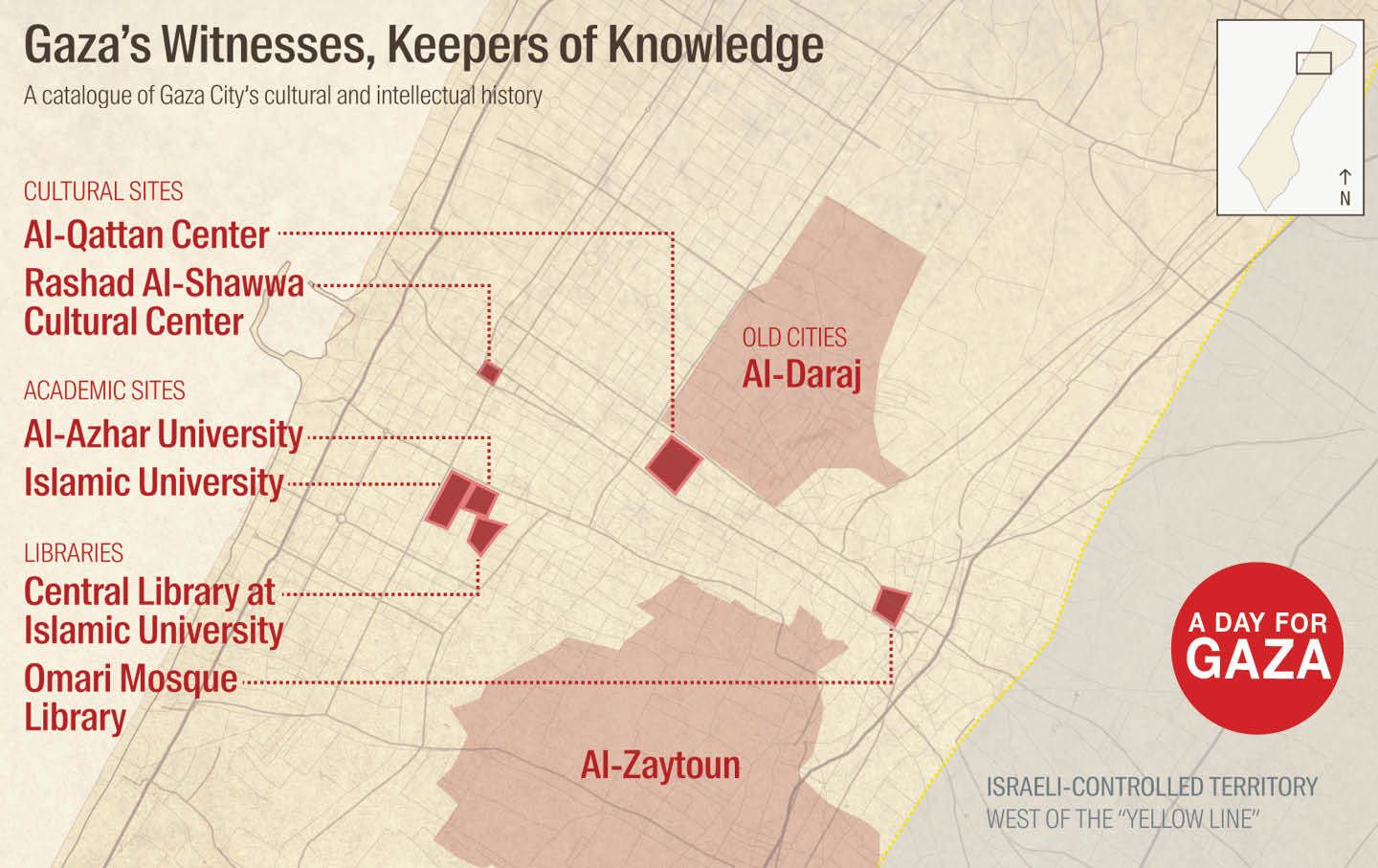

I refuse to accept that Gaza will come to be defined only by destruction and loss. This is a land shaped by long and layered human experiences across history. A natural byway between Africa and Asia, it has long been a meeting point for people, trade, and culture. Lineages of language and conversation, shared traditions and space, all came together to create from our long history a sense of “we”—a nomenclature for our collective identity.

What I seek is a serious attempt to recall this “we” in the midst of a genocide that has never been just a material act of erasing bodies, but a systematic effort to target both spirit and memory. It has stripped places of their soul and their physical appearance, distorted the very image of belonging, and left us, individually and collectively, digging through the ruins of memory for some natural reflection of who we are.

This digging is arduous work, nails forever scraping against loss. Even so, we keep at it, building back schools, cultural centers, libraries in our minds, each one a witness, a keeper of knowledge. But how can we even attempt an answer when these places have been erased? When death arrives daily, stealing our loved ones, our people? How can we shape our identity amid this constant loss? I share some of them here to share a fragment of Gaza’s larger story, to connect past with present and reconstruct an image of who we were and who we remain.

Academic Sites

The Islamic University

A Day for Gaza

-

A Ceasefire in Name Only

-

The Gaza Street That Refuses to Die

-

A Catalog of Gaza’s Loss

-

My Sister’s Death Still Echoes Inside Me

-

What Gaza’s Photographers Have Seen

-

How to Survive in a House Without Walls

-

What Edward Said Teaches Us About Gaza

-

What Happens to the Educators When the Schools Have Been Destroyed?

-

At the Doorstep of Tomorrow

-

“We Have Covered Events No Human Can Bear”

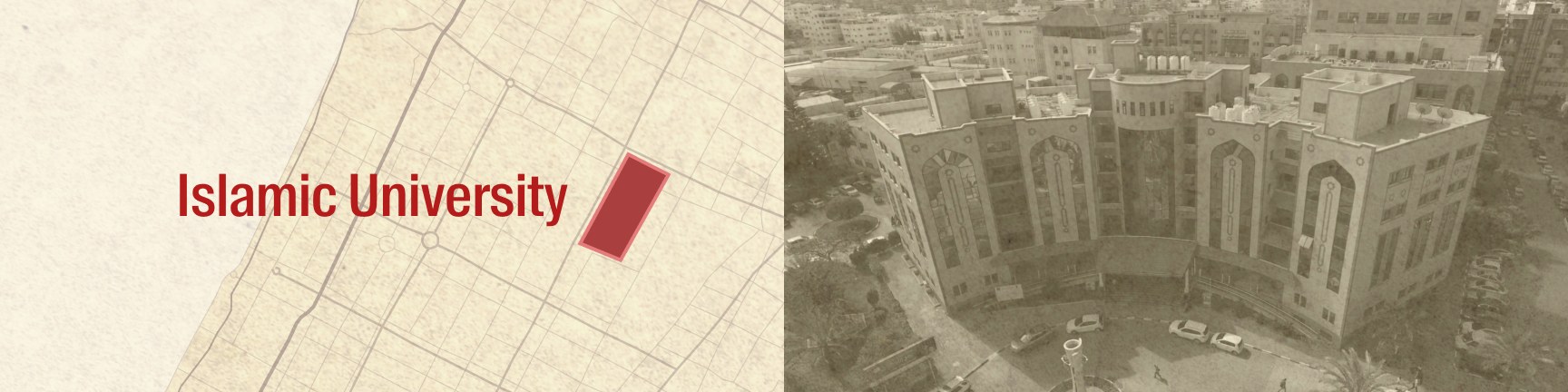

The Islamic University, founded in 1978 as Gaza’s first secondary institution, was more than an academic site. Within its halls, generations of students nurtured curiosity, ambition, and resilience against a backdrop of siege. It was a sanctuary where ideas could thrive, debates could flourish, and a collective consciousness could grow despite the isolation imposed on the Strip. Students from diverse fields—science, media, literature, and religious studies—studied and worked here.

The university became a beacon of higher education in Gaza, ranking first locally and second nationally. Its programs extended beyond knowledge and towars practical empowerment, shaping graduates who could navigate challenges creatively and lead their communities.

On October 10, 2023, Israeli war planes bombed the university, partially destroying more than 500 classrooms in more than 20 buildings. The war that followed took with it many of the university’s professors and staff. Dr. Sufian Abdul Rahman Tayeh, the university president and a leading researcher in physics and applied mathematics, known for his work in optics and advanced materials, was killed with his family in December 2023. Dr. Khetam Al-Wasifi, a biophysics professor and author of more than 50 research papers in fields such as electromagnetic waves and simulation techniques, was killed with her husband in a similar attack. Their loss is tremendous, a ragged hole in Gaza’s intellectual fabric.

Al-Azhar University

Al-Azhar University represented a distinct and complementary academic option to the Islamic University, both in the nature of its programs and its role within Gaza’s educational landscape. It was often chosen for its wide range of undergraduate and graduate programs, including veterinary medicine, agriculture, humanities, law, media, and education. Where the Islamic University focused largely on pure sciences and theoretical research, Al-Azhar offered a more diverse professional and academic formation. Its classrooms and lecture halls were incubators of ideas that connected Gaza to broader Arab and international intellectual spheres; It was also a more open environment, one that encouraged students to engage with one another in intellectual and cultural debates.

Recognized regionally as a top institution, Al-Azhar fostered a generation of students equipped to confront adversity with creativity and knowledge. Its partial destruction signifies a rupture in the continuity of our intellectual life, as the branch in Gaza City was partially destroyed on the same night the Islamic University was hit, and the second branch in the south of the Strip was completely demolished in November 2023.

Al-Azhar had created an intellectual breach in Israel’s blockade, a way out of the suffocating grip of a siege that had lasted 16 years. With its destruction, a lifeline that connected Gaza to the Arab region and the wider world—through conferences, cultural activities, and shared knowledge—has been severed. Al-Azhar offered an intellectual fissure through the blockade, an essential breach whose closure has not yet been fully mended.

Cultural Sites

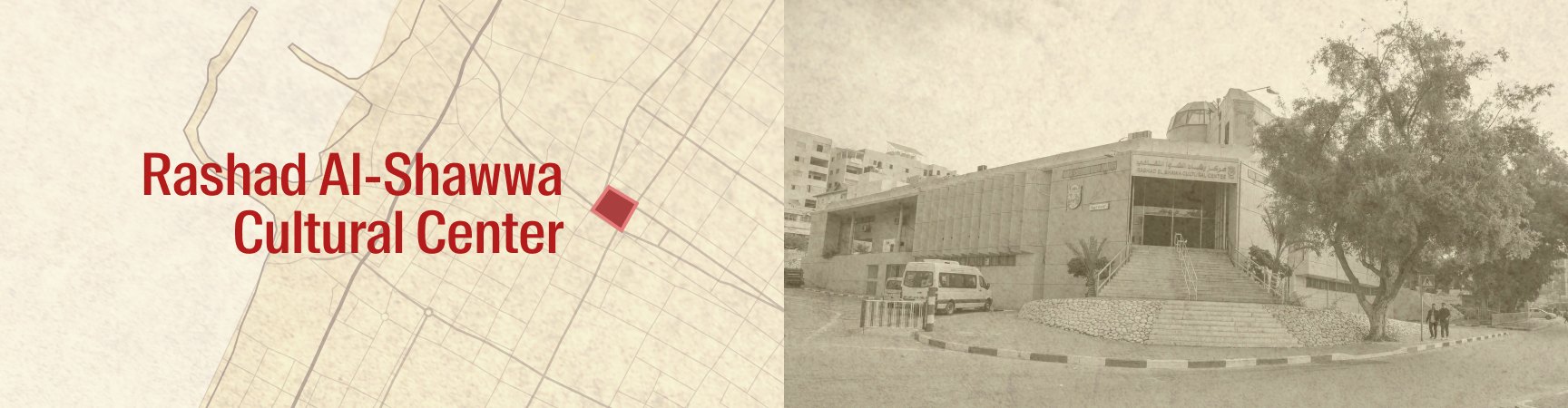

Rashad Al-Shawwa Cultural Center

Founded in 1985 as Palestine’s first cultural center, the Rashad Al-Shawa Cultural Center was intended to break Gaza’s cultural isolation. It hosted exhibitions, performances, and educational programs, cultivating artistic expression among all sectors of the Strip. Palestinian and Arab artists performed on its stage, bringing plays, concerts, film screenings, and other events to the people of Gaza. Among its most prominent figures was Leila Shawa, who designed the stained-glass panels in the main hall. Local Gazan artists, such as Maisara Baroud and Raed Issa, were regular exhibitors, central to the site’s cultural blossoming. Even the building was a work of art; designed by architect Saad Mahfel, it was once shortlisted for the Aga Khan Award for Architecture for its integration of art and local identity. At its center was the Diana Tamari Sabagh Library, one of the largest halls in the Strip, where thousands of books cradled knowledge gathered across diverse fields.

The Rashad Al-Shawwa Cultural Center embodied the city’s spirit of creativity and resilience. Once a place of cultural refuge, the early weeks of the genocide forced it to become a human refuge one as well. Until its destruction in November 2023, it was used as a shelter for displaced people whose homes had been destroyed by the Israeli military.

Al-Qattan Center

The AL-Qattan Center once housed over 111,500 library books and included approximately 25,000 registered members. More than 45,000 children benefited annually from its workshops, while its focus on reading, arts, and writing meant that the center was a central educational and cultural hub, nurturing both children and teachers through a combination of library resources and educational programs. It served as a bridge between generations, instilling knowledge as a discipline and creativity as central to our cultural pride.

Despite severe damage to its infrastructure, the center’s impact remains a testament to Gaza’s ongoing effort to cultivate artistic resilience and learning amid adversity. Its legacy persists through the educators, artists, and children who continue to carry out its mission.

Libraries

Omari Mosque Library

The Omari Mosque Library was far more than a selection of books. At once a spiritual and intellectual refuge, it housed texts that were centuries old. Before the war, it held nearly 20,000 books and manuscripts, including rare texts dating back to the Mamluk and Ottoman periods, some over 700 years old, covering fields such as Islamic jurisprudence, philosophy, astronomy, medicine, and religious sciences. Among those was the Sharh al-Ghawamidh in the Science of Inheritance, by the scholar Badr al-Din al-Mardini, a seminal thesis on Islamic inheritance law estimated to be around 500 years old.

Most of these manuscripts were unique to the library—no copies existed elsewhere. They were irreplaceable, an archival scaffolding for the city’s history. When Israel bombed the library—not just once but again and again—it obliterated not just a building but centuries of accumulated knowledge. Though a local team from the Department of Endowments and Antiquities has managed to rescue 123 of the 228 ancient manuscripts, heritage restoration officials in Gaza have said that much of the damage is irreparable.

Central Library at the Islamic University

As Gaza’s largest library, the Central Library was a cornerstone of intellectual life for students, researchers, and scholars. Its five floors held an expansive collection of academic resources dating back to 1970, along with countless reference works, student theses, and both Arabic and foreign-language books. When Israel bombed the university in October 2023, nearly 240,000 of the library’s books were burned. The university estimates that the continued bombardment destroyed a total of nearly 1 million books. Their destruction is, by that measure, the single greatest intellectual loss in Gaza’s long and turbulent history.

The Old City, Gaza City

Al-Daraj Neighborhood

Al-Daraj is the commercial and architectural center of the old city. The neighborhood is a stage, where the city proclaims itself, a place of commerce, movement, and markets, as well as major cultural and religious landmarks like the Al-Sayed Hashim Mosque, where the grandfather of the Prophet Muhammad is believed to be buried. The sanctity of the mosque—and the Old City by extension—is not something that has been imposed. It whispers through its stillness, in the way light bends as it creeps into the neighborhood.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →The heart of Al-Daraj also contains Qasr al-Basha, the Ottoman-era building later known as “Napoleon’s Castle.” Napoleon Bonaparte is said to have used it as his base during his campaign against the Palestinian city of Acre. Therein lies the story of Gaza itself. A city that has always existed on the world’s map, never a margin, never a quiet passageway.

Al-Zaytoun Neighborhood

Al-Zaytoun is less a neighborhood than a trace of time. The neighborhood moves slowly, the weight of centuries visible in the way its residents saunter. Here, the call to prayer stands beside the sound of church bells. History is inextricable from daily life: The Wilaya Mosque, with its stone inscriptions dating back to the eighth century CE, bears witness not just to architecture but to the living continuity of a city so accustomed to threat. Nearby stands St. Porphyrius Church, a testament to Gaza’s often contested pluralism. It is a neighborhood of difference. A site where religious, social, and human memories sustain. In Al-Zaytoun, the stones are not asked about their faith; they are asked only to endure.

In the absence of all these places that once were, we hold on to their memory, rebuilding them brick by brick. Even so, we who remain also know that memory is not enough. Even now, Gaza continues to bleed. What this means is that the question is not merely, “How do we rebuild?” but “Will we be able to rebuild?” And “What will rebuilding even mean”?

The media sometimes portrays reconstruction or international aid as a remedy, but even if buildings are rebuilt, who will restore the heritage? Who will restore the archives? Who will restore the intellectual memory, cultivated over generations of professors, students, and scholars? Who will restore years of research, writing, study, and experimentation? Who will bring back the voices that will never be heard again? And who will bring back the dead?

Your support makes stories like this possible

From Minneapolis to Venezuela, from Gaza to Washington, DC, this is a time of staggering chaos, cruelty, and violence.

Unlike other publications that parrot the views of authoritarians, billionaires, and corporations, The Nation publishes stories that hold the powerful to account and center the communities too often denied a voice in the national media—stories like the one you’ve just read.

Each day, our journalism cuts through lies and distortions, contextualizes the developments reshaping politics around the globe, and advances progressive ideas that oxygenate our movements and instigate change in the halls of power.

This independent journalism is only possible with the support of our readers. If you want to see more urgent coverage like this, please donate to The Nation today.