Can We Afford to Sit Out the Fight Against Fascism?

Choosing the lesser evil is never inspiring. Still, it’s a choice all of us will have to face.

Rick Blaine picked a side.

(Getty Images)For fans of Dashiell Hammett’s private eye, the new AMC series Monsieur Spade offers a chance to pick up where John Huston’s 1941 film leaves off. The year is 1963, the setting southern France, where the 60ish, retired Sam Spade—played by Clive Owen with a slightly broader American accent than he deployed in Inside Man—is supposed to have come to deliver the daughter of Brigid O’Shaughnessy (the femme fatale from The Maltese Falcon) to her grifter father. True to Hammett (and his rival, Raymond Chandler), the plot can be confusing. But the atmospherics of rural France—still reckoning with its Vichy past while its ongoing, and increasingly rancid, colonial war in Algeria also comes home—are superb.

However, there is one plot point I found particularly hard to swallow. The housekeeper’s grandson, Henri, a soldier, asks, “You were in the army, Mr. Spade?”

“No,” he replies. “I was a conscientious objector.” At first I assumed he was joking. Humphrey Bogart, a CO? But Spade’s lack of military experience is apparently well-known to his neighbors.

I didn’t realize why this bothered me so much until I remembered an earlier scene showing Owen in the rain, wearing a trench coat and a gray fedora and looking like he’s just put Ilsa and Victor Laszlo on their plane out of Casablanca. As with Hammett, who managed to reenlist in the US Army in 1942—no easy feat for a Communist who’d already served in the First World War, where he contracted the tuberculosis that would plague him until lung cancer finished him off—sitting out the fight against fascism was never an option for the owner of Rick’s Café.

Is it an option now? For many progressives, the scene in The Maltese Falcon where Spade (Bogart) tells O’Shaughnessy (Mary Astor) “I won’t play the sap for you” has a painful resonance in election years—especially the part where he adds, “You counted on that.” Taking the base for granted has become the Democratic Party’s habitual vice—to the point that, as Matt Karp notes in this issue, broad swaths of the working class are increasingly identifying with the other party.

And thanks to Joe Biden’s persistent embrace of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and his enduring support for Israel’s unrestrained and criminal destruction of Gaza (see Dana Walrath’s “Dreaming of Never Again” in this issue), many Arab American voters, and increasing numbers of young voters and voters of color, have become bitterly alienated from the president and may well stay home in November.

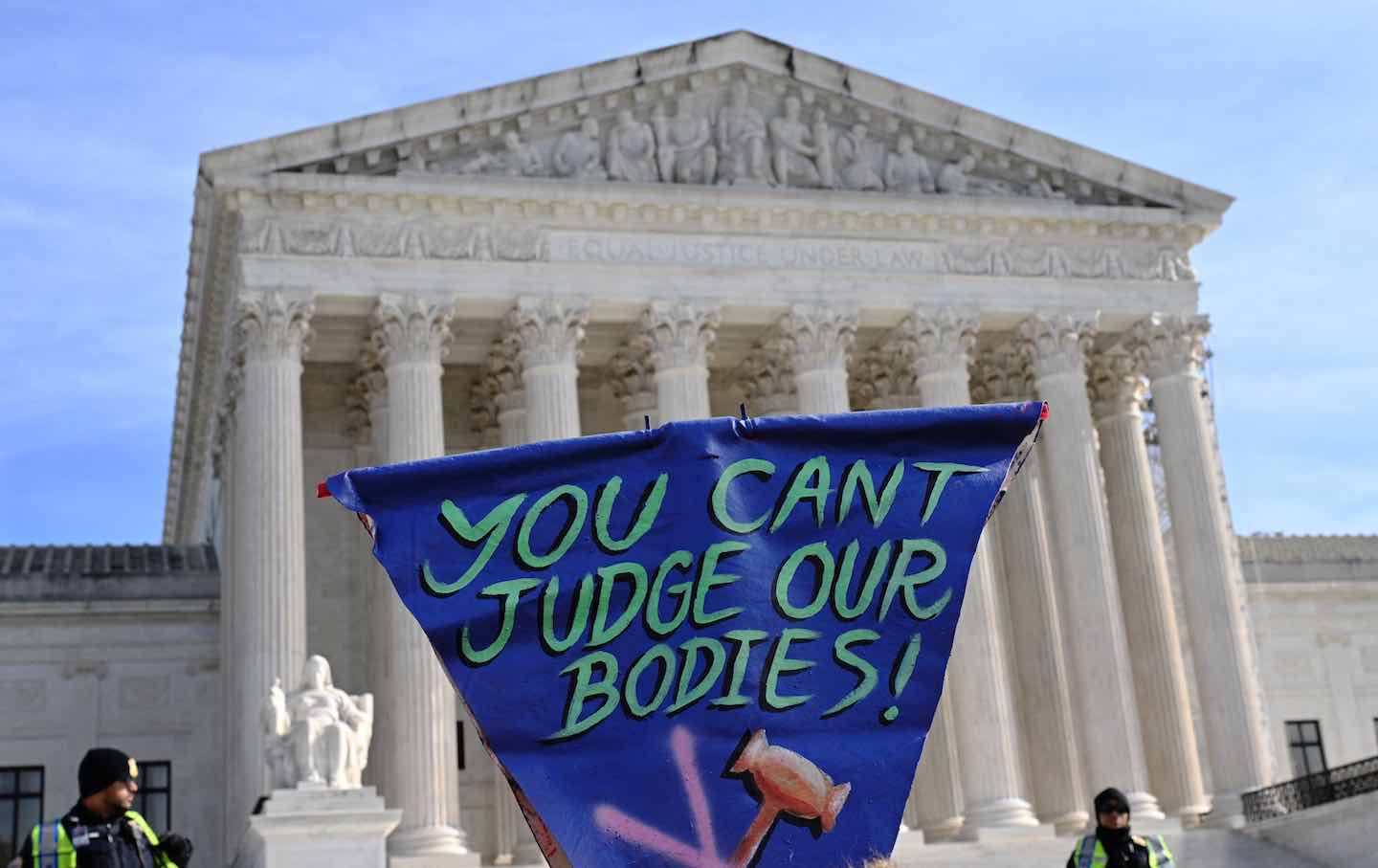

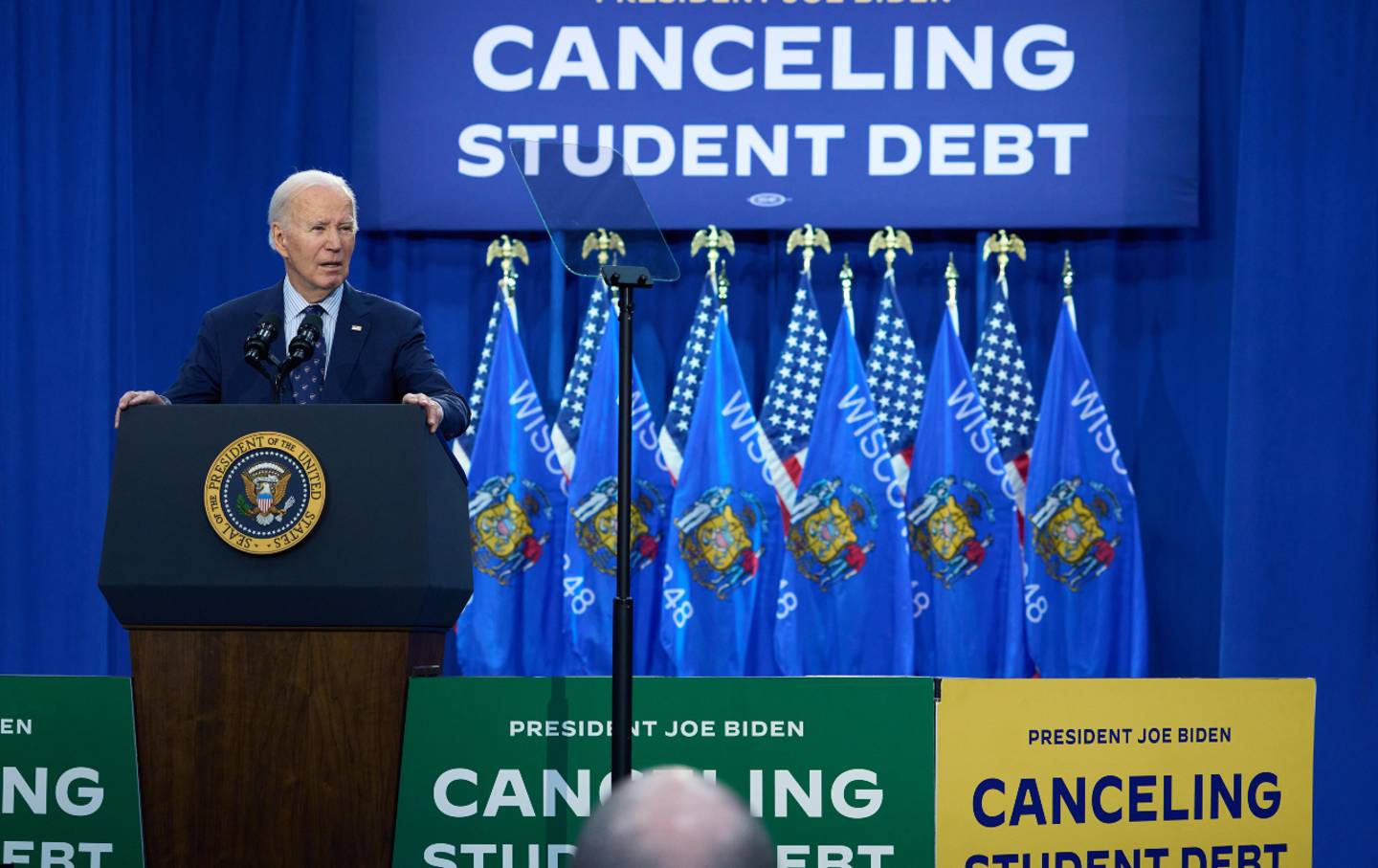

But disappointment with Biden and the Democratic Party extends beyond Israel and Gaza. On securing abortion rights, forgiving student debt, restoring voting rights, and a host of other issues, the president has talked a good game but failed to adequately deliver. While he has successfully steered the country from a serious pandemic recession to record lows in unemployment—and record highs for stock market indices—the benefits of Bidenomics remain unequally distributed, and have barely touched those at the bottom. Even Biden’s recent move to halt the approval of new liquid natural gas terminals—rightly hailed as a huge win for the environmental movement—is a pause, not a permanent commitment.

Speaking of commitment, Katha Pollitt and Elizabeth Gregory both take on the national embrace of pronatalism, while elsewhere in this issue Mike Bonin and Peter Dreier report from Los Angeles, where corporate Democrats seem to regard tenant protection as a greater danger than Republican resurgence. Jeet Heer examines the desi diaspora (and the GOP’s appeal to some children of immigrants), and Jonathan Kozol details the slow strangulation of the country’s urban public schools.

Does any of this justify sitting out an election when the alternative is Donald Trump? When Casablanca’s Rick Blaine claims, “I stick my neck out for nobody,” we know he doesn’t mean it. He’s a veteran of the Spanish Civil War, and on the left, solidarity is perhaps the cardinal virtue. Choosing the lesser evil is never inspiring. Still, it’s a choice all of us will have to face. Will it be Monsieur Spade—or Monsieur Blaine?

D.D. Guttenplan

Editor