In 1870 a black woman named Henrietta Wood sued the white deputy sheriff who, nearly two decades earlier, kidnapped her from the free state of Ohio, illegally transported her to slaveholding Kentucky, and sold her into a life of enslavement that endured until the end of the Civil War. Lawyers for the defendant argued that Wood’s claim to reparations for decades of unpaid labor was barred by a statute of limitations. Nearly 150 years later, as Congress prepared to hear testimony on the idea of reparations, Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell offered much the same argument. “I don’t think reparations for something that happened 150 years ago for whom none of us currently living are responsible is a good idea,” he said, before ticking off the Civil War, the 1964 Civil Rights Act, and the election of Barack Obama as evidence that any debts owed to the descendants of the enslaved have already been largely paid. “I think we’re always a work in progress in this country, but no one currently alive was responsible for that.”

Whether five years after Emancipation or a century and a half later, whether the claimants were the formerly enslaved or their descendants, the United States has steadfastly refused at nearly every opportunity to provide recompense for slavery and its disastrous legacy. The country reneged on its post-Emancipation promise of 40 acres and a mule just a few months after making it. In the 1890s, the federal government brutally crushed a national campaign to give freed black people pension plans. And for nearly each of the last 30 years, Congress has rejected a bill that would merely create a commission to study the consequences of slavery and consider the impact of reparations.

“Any legislation that sought to put black people on an equal footing has been ultimately, if not strangled in the crib, slowly starved,” historian Carroll Gibbs, the author of Black, Copper, & Bright: The District of Columbia’s Black Civil War Regiment, told me. “It’s important to understand that what makes the argument hollow—that it’s too late to do anything because everybody’s dead now—is that the US refused to do it when everyone was still alive.”

Instead, the US government supported and enshrined into law policies that further entrenched white supremacy. Case in point: The only reparations program enacted by the federal government doled out the 2020 equivalent of over $23 million in Treasury Department funds—not to the formerly enslaved but to their white enslavers.

In April 1862, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Compensated Emancipation Act, a congressional bill abolishing slavery in Washington, DC. Less than half a year earlier, he proposed similar legislation in Delaware that stalled in the state’s House of Representatives. Under the DC law—the first emancipation legislation in this country’s history—enslavers were eligible to receive up to $300 for each person they were legally obliged to liberate. (I use the term “enslaver” rather than “slave owner” because it acknowledges the active role those individuals played in keeping human beings locked in a brutal and violent institution. And while the reductive term “slave” has historically been used to strip black people of their humanity, referring to an “enslaved person” makes clear that bondage was a legally enforced position.) No such provision was made for DC’s newly freed black population. Instead, seeing no more use for them, the government offered formerly enslaved people funds only if they agreed to relocate to Haiti, Liberia, “or such other country beyond the limits of the United States.” For this act of self-deportation from the land they had made an economic powerhouse, payment would “not exceed one hundred dollars for each emigrant.”

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

Almost no freed people took up the government on its insulting offer, but DC-area enslavers submitted 966 petitions in the months following the law’s passage. In accordance with eligibility requirements, each filer declared loyalty to the Union and presented itemized descriptions—essentially, invoices—of those they’d enslaved, assigning estimated dollar amounts to each human being. Lincoln empaneled a three-person commission to render a final judgment on the monetary merit of each petition and thus on the black lives described therein.

The trio of DC-based commissioners decided that their first order of business was to locate someone well acquainted with the task of putting price tags on human beings. The Civil War, now entering its second year, disrupted the retail market for enslaved people, causing instability in pricing. Further, the trading of enslaved people—meaning the literal and legal sale of humans from one enslaver to another—was banned in Washington, DC, under the Compromise of 1850. “There are few persons, especially in a community like Washington, where slavery has been for many years an interest of comparatively trifling importance, who possess the knowledge and discrimination as to the value of slaves,” the commission mused in its written report. This area of unpreparedness, the commissioners feared, might interfere with their ability to assess the “just apportionment of compensation” to which enslavers were entitled. Driven by sympathetic concern for the hardships of enslavers denied the legal right to enslave—and to avoid what they unironically referred to as the “interminable labor” of accurately guesstimating people’s worth—the commission brought on Bernard M. Campbell, “an experienced dealer in slaves from Baltimore.”

According to the law, petitioners needed to “produce” the enslaved people for whom they requested compensation, and Campbell’s duties included conducting physical examinations to determine their value, just as at auctions. But the rule of an in-person appearance was often waived. “Many [freed people] left immediately” when Emancipation was announced in the district, seeking out paid work with the military and in parts farther north. Others had run away before the act became law, and in a few cases, enslaved people died just after Lincoln signed the bill.

“Under such circumstances,” the commissioners determined, “it would be manifestly unjust to withhold compensation on account of the inability of the claimant to produce” the enslaved person they claimed. The panel decided enslavers deserved compensation if the people they’d enslaved had escaped no more than two years prior. Petitioners were also asked to include “written evidence” substantiating their claims, but submissions lacking that proof ran little risk of being rejected. This “liberal construction of the act,” the commissioners wrote, sprang from the desire to free the most people (and, of course, pay the most enslavers) without paperwork getting in the way. But the laxity with which this rule was applied highlighted one of the many horrific aspects of enslavement: the ease with which white claims to black bodies and lives could be made.

“Slaves were held, owned, and mistreated so callously that there quite often was not a legal basis for their ownership,” says Kenneth Winkle, a historian at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln and co-director of the research project Civil War Washington. “Slave owners were asked to provide records or bills of sale or receipts or some paperwork. Most of them simply said, ‘I’ve misplaced it’ or ‘I’m not sure I ever had any.’ A white person could claim ownership of an African-American as a slave based on the testimony of two other white people, with no paperwork necessary.”

The Compensated Emancipation Act did not grant automatic emancipation to enslaved people not named in petitions, and some enslavers did not file for compensation by the act’s 90-day deadline, many of them pro-slavery Confederate sympathizers who had no intention of emancipating those they enslaved. To address these cases, Congress passed the Supplementary Act in July 1862, which allowed black folks to submit petitions pleading for their own emancipation and to testify and serve as witnesses—the first time African Americans were allowed to do so in federal proceedings. More than 160 claims were filed by people the commissioners described as “held to service in the District of Columbia by reason of African descent.”

Winkle and his colleagues at Civil War Washington have meticulously cataloged, digitized, transcribed, and posted online nearly all of the petitions filed under the Compensated Emancipation Act. No matter how much you may know about the violence, cruelty, depravity, and terror of slavery, those horrors are revealed anew in the petitions filed. The petitioners’ responses to the bureaucratic formality of noting how they “acquired” other human beings as their property leads to firsthand accounts of black people ripped from their families, treated like hand-me-downs, and enslaved by dint of birth. One claimant wrote that an enslaved woman named “Ann Williams [was] acquired by marriage forty years ago” and that her grandson, Albert Hollyday, “was born while his mother (Eliza since sold) was owned by me.” Another enslaver (this time a woman, of which there were many) reported that a black woman identified only as Delilah was “willed to me by my father in 1816” and that “while my slave and in my survace [sic] Delilah had a daughter named Amanda who while my slave and in my survace [sic] became the mother of said Casper & William,” two young men for whom she requested $450 and $350, respectively.

Enslaved people are listed by name in the petitions, a rarity in documents from the era. That omission was intentional and institutional: Recording the names of the enslaved threatened to confer personhood, and the denial of humanity was the bedrock on which black chattel slavery rested. Erasure of black people from the American historical record is partly located in the practice of reducing the enslaved to nameless head counts or dollar amounts, an obliteration of black existence that continues to impede African American efforts at heritage and genealogical research. Even this tiny recognition of black humanity was conceded only in exchange for federal dollars.

The degrading reduction of black human beings to what were deemed salable traits is both the most salient horror in the petitions and the entire reason for the exercise. Petitioners described the old, the very young, and the sick as having “no value,” rendered worthless by a market that no longer had a way to exploit them. Just as horrifying are the price tags affixed by petitioners to enslaved people for whom they hoped to receive top dollar. Through descriptions of enslaved people’s physical and mental characteristics, the petitioners provided justifications for their compensation claims, highlighting what the commissioners labeled “their intrinsic utility to their owners.” Ironically, these reductive descriptions provide rare glimpses of the human beings named, the lives they lived, and the circumstances they endured.

Linda Harris, for example, is described as a “slave for life,” of “olive brown complexion with full suit of hair, free spoken and intelligent.” Her enslaver writes that Linda is “honest” and “an excellent cook, washerwoman or nurse. During the past year she has had occasional attacks of rheumatism; and is at intervals troubled with weakness of the breast, but has never been compelled to abandon her usual duties.” (As if, one thinks, she had a choice.) Linda’s estimated worth is given as $800. Her enslaver was paid $306.60 for her.

William Alexander Johnson, 22 years old, is described as 5 feet 8 inches tall and “a skillful mechanic, very ingenious in every branch of mechanism…employed in making models for patents, in making and repairing mathematical instruments.” His enslaver requested $2,000 for him; she was compensated in the amount of $657.

Twenty-three-year-old Margaret E. Taylor was the mother of 5-year-old Annie and infant Fanny, both of whom are described as being of “mulatto color.” Their male enslaver notes that “both [were] born while their said mother was held to said service or labor by your Petitioner.” He was given $569.40 for the woman and her children, with Fanny garnering just $21.90.

Gibbs told me that, in addition to the dehumanizing nature of the process, he was consistently struck by the way the descriptions counter the narrative that enslaved people were mentally feeble or lazy. “Despite the claims of proslavery [advocates],” he said, “we’re looking at people whom their masters described in many cases as worthy, competent, skilled.”

Philip Reid is described in a petition as 42 years old, “not prepossessing in appearance, but smart in mind,” and formerly “employed…by the Government.” He was a skilled artisan who helped cast DC’s Statue of Freedom and whose ingenuity succeeded in placing the bronze figure atop the Capitol, where it stands today. For his 33 weeks of labor without respite, Reid was paid $1.25 per day. He was allowed to keep only his Sunday wages; the rest went to his enslaver, Clark Mills. In his claim, Mills requested $1,500 in compensation for Reid. He received $350.40.

“The primary drawback in consulting these records is that most of them were compiled by the slave owners, not by the slaves themselves,” Winkle said. “So this becomes a huge exercise in reading between the lines, so to speak, and certainly not taking this information at face value but analyzing it before putting the pieces together to try to create an authentic collective portrait of who these slaves were, how they lived their lives, and what they accomplished. And surviving slavery was an incredible accomplishment.” He added that the petitions represent “just over 3,300 slaves in the District of Columbia. I always say it’s one-tenth of 1 percent of all the slaves in the American South, but we see them. They are named. We can see them as individuals.”

“Self-petitions” from enslaved African Americans requesting their freedom, many of them written by white pro bono lawyers, provide yet more insight. Phillip Meredith, a 30-year-old black man, lists his enslaver of 30 years as “General Robert Lee.” A corroborating witness notes the general was “formerly of U.S. Army now in Rebel service.” Meredith’s petition was approved.

A more heartrending story is told through the “self-petition” of Mary A. Prather on behalf of herself and her 3-year-old son, Arthur. “Mary says she had permission” from her enslaver to be hired out, according to testimony, but that permission was later rescinded, making her a fugitive and thus ineligible for emancipation under the act. Mary’s and Arthur’s names appear in the commissioners’ report among those “from whom certificates have been withheld.”

Washington Childs wrote in his “self-petition” that he was 33 years old, 6 feet 2 inches tall, with “a large hair mole on the right side of his chin.” He indicated that he was hired out in Washington, DC, “nearly or quite five years last past” by his Virginian enslaver, who would have received all of his wages during that time. His enslaver provided a letter of support for Childs’s emancipation to be presented to the commission. Included in the missive is a citation of an outstanding debt of $60, along with the galling request that Childs pay it off by sending “a barrel of good sugar & sacks of coffee and 2 bolts of cotton & [a] pound of best Tea, that is if you can send the tea & cotton by express.”

His emancipation was granted, and his enslaver was not compensated. But the overwhelming majority of those who submitted compensation claims succeeded in getting funds—often in amounts lower than requested, but at times up to $788. The compensation given to white enslavers helped maintain their financial security and the continuation of white supremacy and power.

“Let’s look at the fortunes of the larger holders of enslaved people—for example, George Washington Young, the largest slaveholder in the district, or Margaret Barber, the second largest,” Gibbs told me. “Barber’s farm, North View, is now the site of the US vice president’s house and the Naval Observatory. She was able to use the money [from the act] and parlay it and invest it.” Another, Ann Biscoe, “had an employment bureau, essentially. She made good money leasing out the enslaved people who were under her control. When compensated emancipation came, she still made out fairly well.”

Eight months after passage of the Compensated Emancipation Act, during his Second Annual Message to Congress, Lincoln proposed a gradual expansion of the policy to any state that freed its enslaved people by the year 1900—a plan that would have condemned enslaved black folks to four more decades of backbreaking, brutally extracted labor and exploitation. Compensation for the formerly enslaved never even came up. Instead, Lincoln again floated the idea that freed black folks could be consensually expatriated to “Liberia and Hayti.” The plan, of course, was not enacted. On January 1, 1863, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which applied only to the treasonous Confederate states, over which the Union had no jurisdiction. Slavery wasn’t fully abolished until nearly three years later, with the ratification of the 13th Amendment.

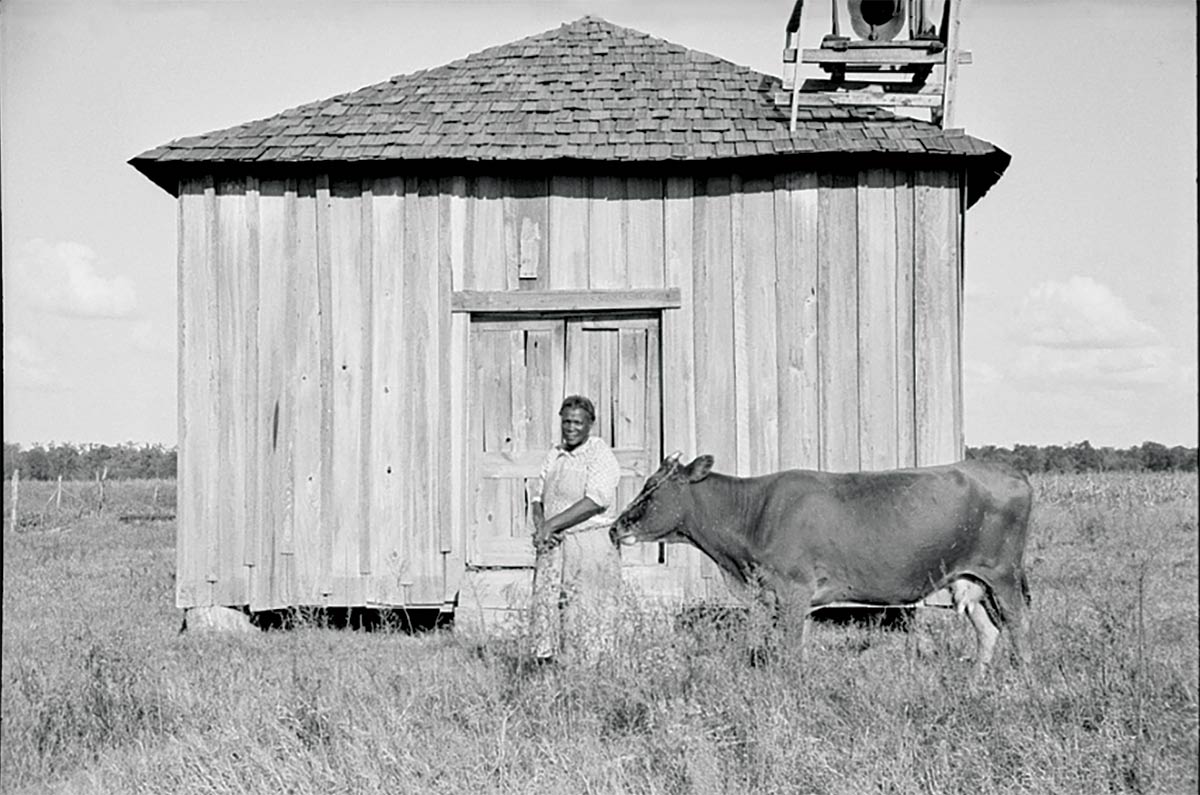

In January 1865, the United States undertook the “40 acres and a mule” reparations program, distributing 400,000 acres of Southern coastal land confiscated from disloyal Confederates to freed black families in plots of “not more than forty (40) acres of tillable ground.” (Union Gen. William T. Sherman, who issued the initial order, also authorized distribution of old Army mules.) Historian and former US Commission on Civil Rights chair Mary Frances Berry noted that by June of 1865, “40,000 freedmen had been settled” on the land and were already “growing crops.” Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson, cruelly reversed the policy, evicting the land’s black occupants and returning their properties to the white Confederate enslavers who had attacked the Union. Many of those black folks would be forced into sharecropping, a Jim Crow form of slavery in all but name.

American history has since been marked by too many calls for reparations to list, each rebuffed in turn by the US government. In 1870, Sojourner Truth unsuccessfully petitioned Congress for land reparations, stating, “I shall make them understand that there is a debt to the Negro people which they can never repay. At least, then, they must make amends.” Walter Vaughan, a white slavery apologist who believed black dollars would ultimately fatten white Southern pockets, wrote an 1890 bill to give freed people pensions like those granted to Civil War veterans. Introduced in Congress by Nebraska Representative William J. Connell, Vaughan’s “ex-slave pension bill” died before becoming law, as did eight other reparations proposals introduced between 1896 and 1903. During the same period, a formerly enslaved woman and mother of five named Callie House cofounded the National Ex-Slave Mutual Relief, Bounty and Pension Association. In 1915, the group sued the US Treasury for $68 million, the estimated amount of taxes collected on cotton between 1862 and 1868. A lower tribunal and the Supreme Court cited government immunity in dismissing the suit. For her temerity, House was charged with mail fraud, convicted by an all-white jury, and sentenced to a year in the Missouri State Penitentiary. Nearly 50 years later, reparations advocate Audley “Queen Mother” Moore secured enough petition signatures—over 1 million—to compel President John F. Kennedy to meet with her, but no legal remedies followed. The US District Court for the Northern District of California dismissed a 1995 reparations lawsuit, and the Supreme Court declined to hear a 2007 class action case against corporations that benefited from black enslavement.

In 2019 the House of Representatives held a hearing on HR 40—the number refers to Sherman’s unfulfilled promise of land—a bill that was introduced in every Congress from 1989 to 2017 by Michigan Representative John Conyers. Unceremoniously killed in committee for nearly 30 years, HR 40 would not compel federal payouts to the descendants of enslaved people but instead would merely impanel a commission to examine the impact of “slavery and its continuing vestiges.” In taking up the bill’s sponsorship, Representative Sheila Jackson Lee noted that it would help illuminate the statistics that show the “stunning chasm between the destinies of White America and that of Black America.” For example, the median wealth of white families is currently estimated at $171,000; for black families, it is $17,600—approximately a tenfold difference. Fewer than 10 percent of white families have zero or negative net worth, while nearly 20 percent of black households do. Discrimination against black people in mortgage lending, historically and today, has hobbled opportunities for homeownership, the source of two-thirds of equity for American households and one of the most reliable forms of intergenerational wealth. And while we’re on the subject of black folks being denied property, it seems like a good moment to note that if those 40 acres and a mule had been distributed as promised, the land would be worth about $6.4 trillion today.

If there were an actual interest in ending those disparities, Congress would at the very least support studying the numbers. Instead, opponents of HR 40 argue against even investigating the issue. That opposition, including McConnell’s dismissive remarks, demonstrates the ahistorical American self-mythologizing at the heart of the country’s bitter opposition to slavery reparations. The Senate leader and his ilk are fighting an ideological war to defend the lie that slavery was a historical anomaly, an inconsequential blip on an American moral arc that always otherwise bends toward racial justice. It’s an attempt to rewrite history, omitting how the denial of reparations shortchanged black freedom and omitting the policies of Jim Crow, redlining, mass incarceration, and unstinting white terror against black success. Ta-Nehisi Coates, the author of the highly influential 2014 Atlantic article “The Case for Reparations,” directly addressed McConnell—whose family enslaved black human beings—in his testimony on HR 40. “We recognize our lineage as a generational trust, as inheritance, and the real dilemma posed by reparations is just that: a dilemma of inheritance,” Coates stated. “It is impossible to imagine America without the inheritance of slavery.”

Recognition of this fact has very slowly dawned on a smattering of institutions. Yale, Brown, Harvard, William & Mary, and more than 50 other members of the Universities Studying Slavery consortium have acknowledged the role of black enslavement in their early funding, founding, construction, and maintenance. (The collective includes schools in Britain, which also gave reparations solely to enslavers; the taxpayer-funded payments of $3.9 billion ended only in 2015.) To atone for their ties to slavery, Virginia Theological Seminary, Princeton Theological Seminary, and Georgetown University have all established reparations funds. In November 2019 legislators in Evanston, Illinois, voted to use taxes on legalized marijuana to pay reparations to a community “unfairly policed and damaged” by the War on Drugs. And in 2005, JPMorgan Chase apologized for its connections to black chattel slavery and established a $5 million scholarship fund for black students. In 2019 then–presidential hopeful Cory Booker introduced a reparations bill in the Senate that was cosponsored by fellow candidates at the time Elizabeth Warren, Kamala Harris, Kirsten Gillibrand, and Amy Klobuchar, as well as current candidate Bernie Sanders.

Henrietta Wood, the woman who sued for reparations just five years after the end of the Civil War, won her case, although she received only a fraction of her original demand—in itself far less than she was owed, which was a price too great to be quantified. Her story remains a near singular example of US willingness to make some form of reparation for black enslavement. Like many who have studied the enslavement of black people in the United States and its destructive legacy on black lives, Kenneth Winkle believes there should be an effort to study reparations and determine some kind of corrective.

“There must be recompense for descendants of slaves,” Winkle says. “I’m a historian, and I devote most of my thoughts to the past and probably too little to the present. And I’m not certain what that compensation can or should consist of—but there needs to be an official recognition of the injustice that Americans collectively inflicted, at the time of their emancipation, on about 4 million African Americans who survived to be able to enjoy their emancipation, and the government participated in committing that injustice.”

What is so often labeled America’s “original sin” is, in fact, a wrong this country continues to commit. Reparations would not only represent a genuine effort to redress the United States’ long history of racial discrimination, white terror and anti-black lawmaking but also a recognition of the ongoing harm this country inflicts against its African American citizens.