The Activists Fighting for Dignity for Incarcerated Pregnant Women

Prison doulas and legislative interventions can be a lifeline for incarcerated pregnant women. But the most important solution is to abolish prison births altogether.

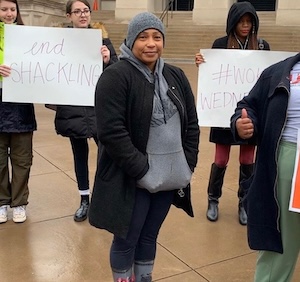

After utilizing a doula while pregnant and incarcerated, Autumn Mason was inspired to become a prison doula herself and to train other women to do the same.

(Courtesy of Autumn Mason)Autumn Mason was eight months pregnant when she was sentenced to more than two years in prison. “I was in a fog,” she described. “I didn’t even tell my family or my partner that I was pregnant until…pretty much about a month before I went in for sentencing.” Autumn had been assured by her attorney and prosecutors that she would be allowed to remain in St. Paul, Minn., with her child under a downward departure sentencing with strict supervision. But the judge overruled that agreement and sentenced Autumn to 32 months in prison. That’s when the walls closed in on her. I’m going to deliver this baby in a prison surrounded by real criminals, she thought to herself. How could I mother behind bars?

Thankfully, Autumn was wrong about the women she was incarcerated with. They were not too different from her; they were nurturers who reassured her that she had options for protecting her baby. One woman suggested that Autumn request support through Minnesota’s Prison Doula Project. Having worked with a doula for the birth of her first child, Autumn leapt at the chance to have that same support this go round and quickly signed up. She had no idea that experience would change the trajectory of her life once she was released from prison, propelling her to become a leading advocate for prison doulas at a time when the number of women being imprisoned nationwide remains alarmingly high and when Black maternal mortality rates continue to climb.

After signing up for a doula, the process of being matched can be riddled with delays. Fortunately, Autumn was matched right away due to how far along in her pregnancy she already was. Even with support from a doula, Autumn’s final weeks of pregnancy were plagued by infrequent doctor’s appointments and one particularly disturbing visit with a medical “professional” who had the wrong charts and nearly prescribed Autumn someone else’s medication.

Before long, Autumn was in labor. “My three roommates were very loving. We were incarcerated in a no-touch facility where you cannot have any physical contact with each other,” Autumn recalled. “They were breaking the rules to…[bring] me hot towels or drinks, and rubbing my back and shoulders.” When Autumn’s contractions grew closer together, she called for guards to get her to the hospital and was strip searched before being transported. Even in the hospital, two officers loomed over her as she labored. “I just remember feeling like an animal at the zoo,” she noted.

Autumn was one of the first women in the state to deliver a child after Minnesota passed a law, in 2014, abolishing shackling for women in labor. And her doula through the MN Prison Doula Project was there for her delivery as well as after she was discharged and separated from her newborn. “My doula was able to capture pictures of my baby and I that I cherish to this day and which many other women who give birth behind bars” do not get to experience. Still, being separated from her child during those pivotal first years of life, while she served out the rest of her sentence, was devastating for Autumn.

Though her experience was less than ideal, Autumn was lucky in many ways. Pamela Winn’s pregnancy behind bars in Georgia looked a lot different. During a court appointment, Pamela’s arms and legs were shackled so tightly that she tripped and fell while stepping into the transporting van. “Two officers picked me up and put me back on the van without checking or asking if I was okay,” Pamela said. Within days, Pamela went from spotting to bleeding. As a former registered nurse, she knew something was wrong, but it took weeks to be seen by doctors. When she was finally able to meet with the medical director and a contracting physician, it was offered as a “professional courtesy” because they shared mutual colleagues. Even then, they said that they couldn’t help her because all decisions came down to wardens and correctional officers.

After sixteen weeks of requests, denials, appealed requests, and incessant delays, Pamela was finally approved to get the care that she needed. One night before her scheduled appointment, Pamela felt a warm gush of fluid between her legs but couldn’t see what it was because of how dark her cell was. “I was crying, hurting, and afraid,” Pamela remembered. Other incarcerated women began banging and screaming on Pamela’s behalf. It wasn’t until five hours later that an officer finally opened the door.

In the light from the hallway, Pamela saw that the warm gush she’d felt was blood. “I was not only afraid for my baby but also for my own life.” By the time she arrived at the hospital, Pamela had miscarried.

Incarcerated women regularly face poor treatment during their pregnancies, including inadequate nutrition to support growing a healthy child, harmful cavity searches, and delivery while shackled or in solitary confinement. Even when gains are made in some parts of the country, there is no national standard of treatment for incarcerated pregnant women despite women being the fastest growing prison population in America, and the majority of those women are already mothers. Nearly 40 US states have banned the practice of shackling women during childbirth and yet, a study talking to labor and delivery nurses in America’s prisons found that many incarcerated patients were shackled sometimes to all of the time. This often happens due to confusion over legislative changes and guard discretion over who is considered a “security risk.” Yet, mainstream reproductive rights spaces often ignore this aspect of the fight to achieve reproductive freedom for all.

The odds are stacked against incarcerated pregnant women in a country where it is increasingly difficult for Black women to control their own fates and their children’s futures. Incarceration only exacerbates that danger. Since her own harrowing experience, Pamela Winn has become known as “The Face of Dignity for Incarcerated Women.” After being released from prison, in 2013, Pamela founded RestoreHER and has spearheaded successful campaigns like the passage of HB345 in Georgia, which banned shackling and prohibited solitary confinement for pregnant and postpartum women. Similarly, Autumn was inspired to not only become a prison doula herself but to also train other women to do the same. “Simply having another person in that room to witness the injustices that they try to put us through matters so much,” Autumn insists.

Through the Minnesota Prison Doula Project, she has trained over 100 prison doulas. Unfortunately this still isn’t nearly enough to meet the demand for doulas and Autumn notes that even with an increasing number of certified doulas, many detention centers don’t make the services accessible to those incarcerated there. “We are moving the needle towards a more humane practice for birthing people that are involved in the criminal justice system, but it is a slow process,” says Autumn. “Even though we’ve passed all these pregnancy justice bills across more than 25 states, we still get calls all the time about women being shackled during birth,” notes Pamela. “We also see stories in the media where women are still delivering alone in solitary.”

There are some who’d argue that women who want to control their pregnancy experiences should simply stay out of the carceral system, but this ignores the reality of who incarcerated women are. “Many are those that have experienced gender based violence or criminalized poverty,” noted Fatima Goss Graves of the National Women’s Law Center. For example, even as Minnesota has created an alternative placement program for incarcerated pregnant and postpartum women, the Prison Policy Initiative explains that the criminalization of addiction, mental illness, and poverty has distinctly driven women’s incarceration. To add to the unique way women are ensnared in the criminal legal system, Goss Graves adds, “we’re also seeing a lot more examples of people having their pregnancies or miscarriages turned into a criminal matter.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →According to new data from Pregnancy Justice, in the first two years following the fall of Roe v. Wade, prosecutors initiated over 400 criminal cases against women across 16 states relating to their pregnancies or pregnancy losses. Goss Graves and her team are hypervigilant of this punitive dynamic and work tirelessly on campaigns for women’s rights, which includes advocating for incarcerated women. Across NWLC’s 50 year history, they were one of the earliest groups to have a project that examined the support women need exiting prison. It’s why, as part of their recently launched 75 Million Campaign, NWCL is sounding the alarm about the 190,000 incarcerated women workers who are so often invisibilized. “Whether it is your ability to support and contribute to your family while incarcerated or once you leave, economic and worker protections are also important parts of this conversation,” says Goss Graves.

Black women are disproportionately affected by mass incarceration, financial exploitation, and attacks on bodily autonomy. Prison doulas and legislative interventions for conditions of confinement can be critical bridges of advocacy. But they are still temporary solutions. Pamela and Autumn agree that the most important solution is to abolish prison births altogether.

Right now, Pamela and her team are working towards implementing The Women’s CARE Act in states across the nation which would allow for sentence deferment, promote alternative sentencing, ensure pregnancy testing at arrest, and require improved data collection all around. The bill has already passed in Colorado and is in the works in California, Alabama, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia with preliminary conversations about bringing it to Texas, Illinois, and Ohio. “Women don’t need to be in prisons and jails if they’re pregnant,” Pamela urges.

Autumn is inspired by models elsewhere like Germany’s “Principle of Normality,” where incarcerated parents have access to specialized housing that emphasizes community integration and family contact. In these facilities, mothers can birth, breastfeed, and raise their children during their sentences while working and making an income that supports their eventual reentry. Similar mother-baby facilities also exist in the Netherlands and Denmark.

As a storyteller funded and trained through Represent Justice’s flagship Ambassador program, Autumn is focused on portraying honest and compelling narratives as a vehicle for change. She believes that when we see the real people shaped by our inaction, we are ignited to speak up and do more. “My personal commitment at this time is to create healing spaces for families to return to and to get the resources and the skills that they need to live successfully outside of the criminal justice system after release,” Autumn explains. “To give families and children a place to unite, to love on each other, and to grow together.”