Police Can Be Held Liable for Killing a Dog but Not a Black Person

In back-to-back rulings on when cops should be afforded qualified immunity, an appeals court came to radically different conclusions.

(inhauscreativ / Getty Images)

I like dogs. I’m a “dog person.” I think people who don’t like dogs are… a little weird. I think people who murder dogs, like South Dakota Governor Kristi Noem, are psychopaths. I have no problem eating meat or killing mice or launching a tactical nuclear strike on a nest of wasps, but I think the law should elevate pets to a higher state of legal protections than mere property.

But, and this is going to sound weird to a lot of folks, I like Black people more than dogs. Not every Black person, to be sure. In fact, I particularly detest Black people who actively campaign to be little more than the white man’s pet, as is the case with South Carolina Senator Tim Scott. But since Black people are, you know, people, while dogs are non-people, I think the law should offer more protections to Black people than to people’s pets. At the very least, I do not think the law should treat Black people worse than dogs.

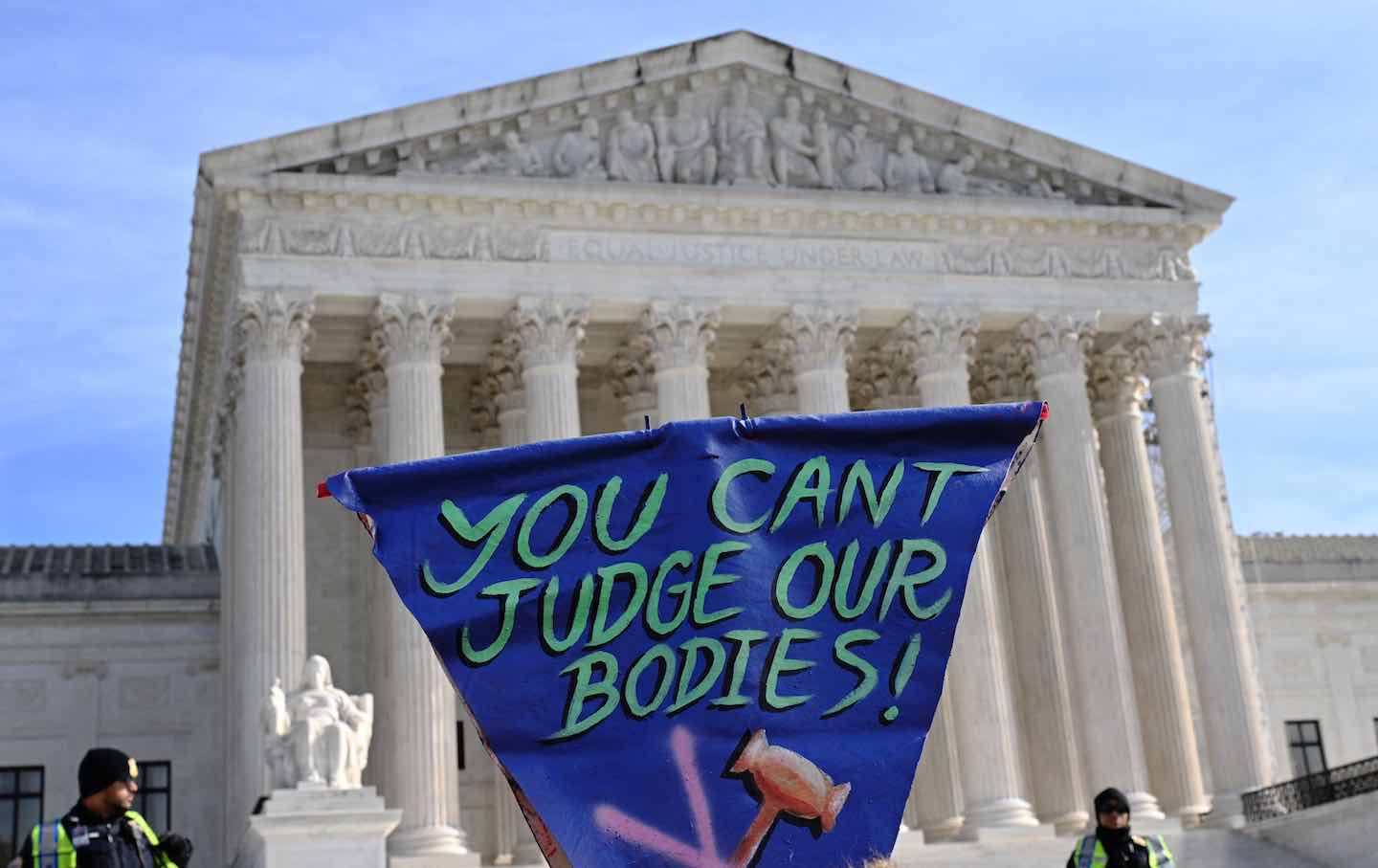

Apparently, this is a controversial opinion—at least for the judges on the US Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit. The 11th Circuit covers Alabama, Florida, and Georgia, three states with a lot of dogs and Black people. In two rulings handed down this week, the circuit took wildly different stances on the protections afforded to dogs versus Black people.

Both cases involved questions about qualified immunity. In each, plaintiffs tried to sue law enforcement for monetary damages after law enforcement screwed up. But the outcomes were decidedly different.

As a reminder, agents of the state, like the cops, are generally entitled to immunity from individual liability claims if those agents are acting in their official parameters. But there are exceptions where the immunity shield can be “pierced” and law enforcement can be forced to pay damages for their actions.

In Sylvan Plowright v. Miami Dade County, the 11th Circuit granted an exception to the qualified immunity rules. In that case, Miami resident Sylvan Plowright called 911 to report a trespasser on a vacant lot next to his home. When the cops showed up at Plowright’s home, they immediately drew their guns on him—the guy who had called for help—and started shouting at him to show them his hands. This is where I mention that Plowright is Black. At some point, Plowright’s 40-pound American bulldog, Niles, came out of the house and into the driveway. The cops started shouting at Plowright to restrain the animal, but before he could, they tased the dog. The attack left Niles prone and incapacitated, but that did not assuage the cops. One of them, Sergio Cordova, shot the dog, twice, killing him.

Plowright sued the cops for damages. A unanimous panel of 11th Circuit judges ruled that the officers were not entitled to qualified immunity. They held that “no reasonable officer in Cordova’s position could have believed that Niles [the bulldog] posed an imminent danger.” The panel said it was a “novel” case, meaning that the circuit had never before considered whether qualified immunity could be pierced in a situation involving a pet. But they found that established principles of qualified immunity should not extend to the wanton and needless murder of a dog.

It’s a good ruling! The cops should not be allowed to run around electrocuting and murdering dogs. The problem arises when you compare this ruling, which the 11th Circuit issued on June 5, to the one it issued the day before in a different qualified immunity case.

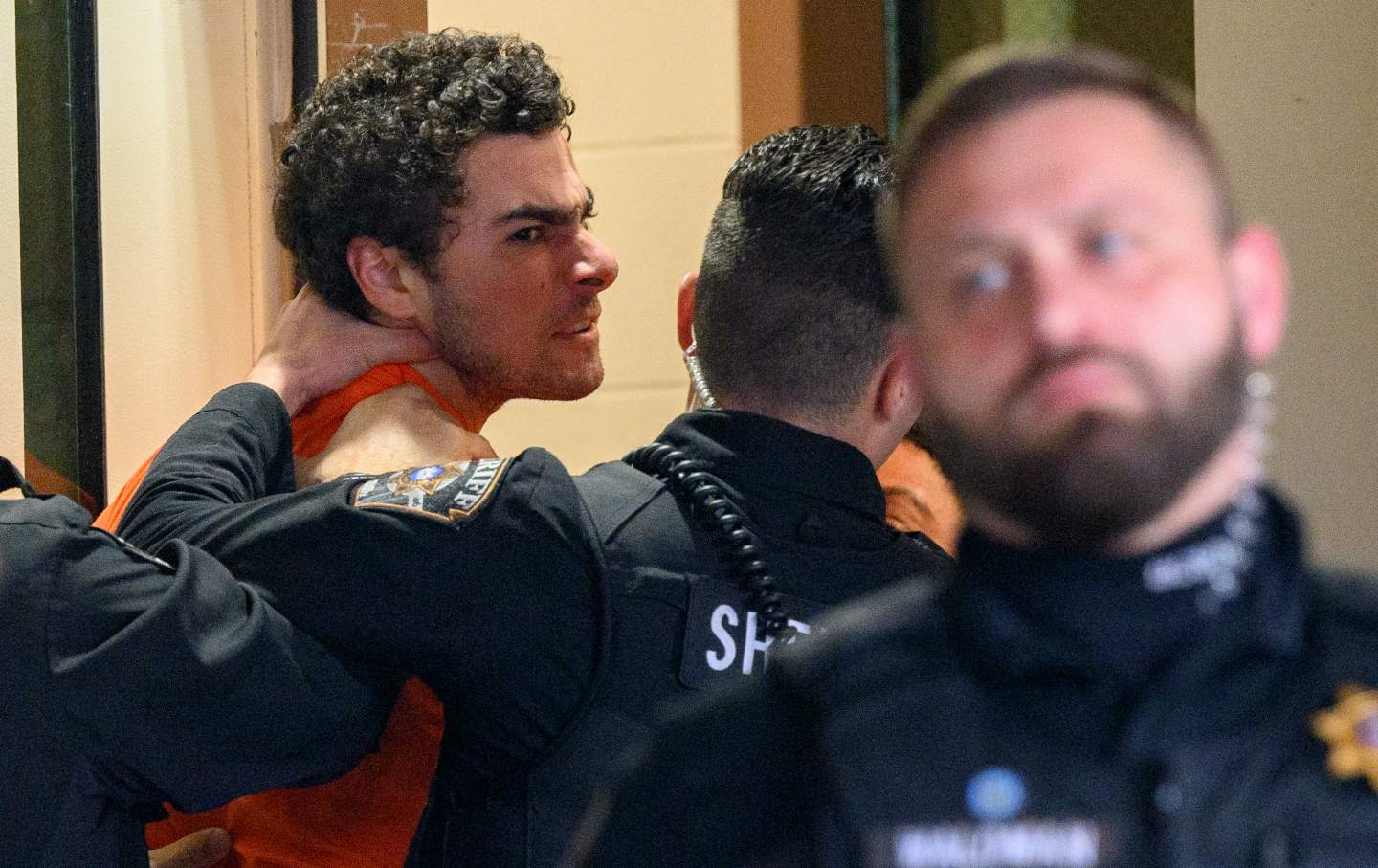

In this earlier ruling, in a case named Robinson v. Sauls, the 11th Circuit determined that members of law enforcement were entitled to qualified immunity—and were thus protected from an excessive force claim—after they shot a Black man 59 times, killing him.

The officers in question were part of a joint task force of local law enforcement and the US Marshals that was attempting to serve a warrant on a Black man, Jamarion Robinson. The task force tracked Robinson to his girlfriend’s house in Georgia. Officers knocked on the door, spoke to the girlfriend, and demanded that Robinson come outside. He apparently refused, so the cops broke into the house by force. Once they were inside, the cops claim, Robinson pointed a gun at them from a second-floor landing. The cops opened fire, shooting at him 59 times. When they stopped shooting, they set off a flash-bang over his limp body. When he didn’t respond to the flash-bang, they handcuffed him. Only then did they call for medical attention. A medical examiner later found that Robinson had suffered 75 entry and exit bullet wounds; he died at the scene. The officers were uninjured. It’s not clear that Robinson ever fired his weapon.

After his death, Robinson’s mother, Monteria, filed what is known as a Bivens Actions. Named for the case Bivens v. Six Unknown Named Agents, a Bivens action is a specific kind of exception to qualified immunity that can be applied to federal officers. In her claim, Robinson’s mother said that she could prove that law enforcement used excessive force, violating her son’s constitutional rights under the Fourth Amendment and thus stripping them of their qualified immunity. But a unanimous panel of 11th Circuit judges said no.

They said that it was a novel case because the task force at issue was a combination of local and federal authorities. Bivens explicitly applies to federal agents, and while the people who shot Robinson 59 times were doing so at the behest of the US Marshals Service, and had been deputized to perform the functions of deputy marshals, the circuit argued that the task force represented a “new category of defendants” that existed outside the parameters of Bivens.

Instead of allowing her lawsuit to go forward for federal violations, the judges suggested (and I am not cruel or evil enough to make this up) that Robinson’s mother file a complaint with the US Marshals or the Department of Justice. They literally shared in their opinion a link to online resources for Robinson to explore, dismissing her cries for justice.

The judge who wrote the unanimous opinion essentially telling a grieving mother to leave a bad review on the US Marshals’ website is Jill Pryor, a Barack Obama appointee. Pryor was also on the panel that ruled unanimously to give justice to the dog. This is where I tell you that Pryor and all the judges on both 11th Circuit panels at issue here are white.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Both of these cases involved “novel” legal circumstances. There was no direct precedent governing either ruling. Yet the 11th Circuit saw the slaying of a dog as something clearly outside the scope of normal official duties, while the slaying of a Black man was just another day at the office for this country’s law enforcement. The law won’t protect cops who unconstitutionally kill a dog but will protect cops who unconstitutionally kill a Black man.

I’m sure cops in Alabama, Florida, and Georgia will notice the essential takeaway from these two cases: Shoot the Black man, but leave the dog alone. I promise you that if the trigger-happy cops had killed Plowright-the-Black-Man instead of Niles-the-Bulldog, the 11th Circuit would have granted the cops qualified immunity. That’s where we are in this country.