The US Medical Establishment Is Making One of Its Worst Mistakes—Again

By ignoring the horrors in Gaza, our healthcare elites are adding to a shameful historical record of denialism.

The world’s most influential medical journal has finally confronted its failure to address an unfolding genocide—over 80 years after the fact. Last month, the historians Joelle Abi-Rached and Allan Brandt were invited to reflect on The New England Journal of Medicine’s choice to remain silent from 1935 to 1944 about the escalating horrors of the Holocaust—particularly the crimes committed by the Nazis in the name of medical science.

In their conclusion to the piece, Abi-Rached and Brandt wrote, “As we explore historical injustices in the Journal and beyond, we must consider not only expressions of explicit and implicit bias, discrimination, racism, and oppression, but also how rationalization and denial may lead to silence, omission, and acquiescence—considerations that are critical to understanding systematic historical injustices and their powerful, tragic legacies.”

The article is part of a series, “Recognizing Historical Injustices in Medicine and the Journal.” Its stated purpose is to “enable us to learn from our mistakes and prevent new ones.” But, in a bitter twist of irony, it has been published at a time when the NEJM is repeating the very mistakes it now claims to be rectifying.

For the last seven months, the world has witnessed Israel’s relentless attacks on Gaza—and, more specifically, its war on Gaza’s medical system. We have seen the indiscriminate murder of health workers and patients in their hospital beds; the bombing of hospitals and clinics; the targeted destruction of health and sanitation infrastructure; the blockade of humanitarian aid and essential medications as famine is used as a weapon of war; and the infliction of conditions that are designed to be incompatible with human life.

Related Stories

These actions represent precisely the kind of systemic racism and sustained state violence that the The New England Journal of Medicine’s historical reflections are intended to push the medical profession to help prevent. Yet, just as it did so many decades ago, the NEJM has declined to use its pages to even acknowledge, let alone condemn, the slaughter and starvation Israel is inflicting on civilians with US military aid.

The journal’s failure to acknowledge the existence of Palestinians is nothing new. In fact, it has not published any mention of the health effects of Israeli medical apartheid, occupation, military incursions, or blockades on Palestinians since 1986. By contrast, since 2015 alone, it has published articles on war-related health outcomes in Ukraine, Syria, and Yemen.

De facto censorship of scholarship on Palestine and criticism of Israeli state violence against Palestinians is well-known as part of “the Palestine exception.” Many of our colleagues have submitted articles about health conditions in Gaza and the West Bank both before and after October 2023, only to receive prompt rejections without outside review.

These editorial choices are emblematic of a much broader disregard for Palestinian life that pervades US medical organizations and their powerful lobbies. Not a single major US medical society nor journal has opposed the US government’s ongoing material support for the destruction of Gaza. The profession’s largest lobby, the American Medical Association (AMA), rejected calls even to endorse a cease-fire and protections for Palestinian health workers. And nearly all major US-based global health actors—from academic research centers to nongovernmental organizations like The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (and the many influential health organizations, researchers, and journalism outlets it funds) to public agencies like the CDC and USAID—have abstained from taking any meaningful stand against the obliteration of healthcare in Gaza. This collective refusal by US health institutions, which represent the largest sector of the nation’s economy and wield considerable political power, to address the rights of Palestinians carries substantial material consequences.

Israel is currently inflicting the deadliest violence against civilians since the Rwandan genocide in 1994. No conflict since has led to more rapid loss of life than the ongoing attacks on the Gaza Strip, which have been 10 times more deadly for children than any other recent conflict––and not by accident. A recent peer-reviewed analysis of satellite images from the first 42 days of the ongoing Israeli campaign against Gaza shows extreme levels of destruction of health, water, and education infrastructure. According to the study, by November 22 of last year, half of all critical civilian infrastructure in Gaza had already been damaged, a third destroyed, and even the Israel-designated evacuation corridor bombed. The data show clustering of Israeli attacks on these essential civilian sites, including Gaza’s medical facilities, suggesting that Israel has been, in the words of the 1948 Genocide Convention, “deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part.”

On January 26, 2024, the International Court of Justice ruled in South Africa v. Israel that Israel was plausibly in violation of the Genocide Convention for its treatment of Palestinians. The court ordered emergency provisional measures to halt all activities in violation of the convention and “to take immediate effective measures to enable the provision of urgently needed basic services and humanitarian assistance” to Palestinians in Gaza, who face the worst famine since World War II. A key component of the court’s deliberations falls squarely within the purview of health scholars and journals: a review of Israeli attacks on Gaza’s health and sanitation infrastructure.

In “The War on Hospitals” published by Boston Review last December, Abi-Rached—one of the authors of the article on The New England Journal of Medicine’s failure to condemn Nazi Germany—characterized Israel’s attacks as “the intentional undermining of the entire health care system.” Abi-Rached piece foreshadowed the ICJ’s ruling on charges of genocide against Israel, writing, “The attacks have made clear that the repression of Palestinian rights now has a new feature: the systematic destruction of the very institutions that sustain life.”

On March 28, 2024, by ruling in favor of additional emergency measures to try to stop Israel’s use of famine as a weapon of war, the court officially recognized what disappointingly few in the US medical field have been willing to publicly acknowledge: a preventable, large-scale deliberate decimation and starvation of human beings is underway.

The US medical profession’s silence has also persisted in relation to the participation in genocidal violence by medical workers in Israel. Nearly 100 Israeli physicians signed a public letter calling for the bombing of Al-Shifa Hospital, for example, and, according to reporting by the Israeli newspaper Haaretz, an unknown number of Israeli physicians are now engaged in the torture of Palestinians who are confined, most without charges, inside Israeli detention facilities—from so-called field hospitals to prisons.

But in the face of such horror and the documented killing of at least 493 health workers in Gaza, there are also Israeli physicians who, at considerable risk to themselves in light of the Israeli government’s current repression of dissent, are criticizing these barbaric acts and abdications of ethical responsibility, and appealing to their government to stop violating international law and to respect basic medical ethics. The US medical establishment has an opportunity—indeed, an obligation—to support these Israeli physicians’ efforts to protect the most basic integrity of the medical profession and to affirm the value of every life.

Why has it failed to do so?

One important factor is the medical profession’s long-cultivated denial of the intrinsically political nature of medicine and public health. By selectively appealing to political neutrality when convenient, both institutional leaders and rank-and-file doctors can retreat from any ethical responsibility beyond the bedside—all while their lobbying groups carry on with explicitly political projects focused on maximizing the field’s profitability.

A second factor is the vulnerability of doctors and nonprofit institutions in America’s privatized health industry, which ensures few job protections and supports an intensely hierarchical professional culture characterized by very little tolerance for ethical dissent. Many doctors fear their careers will be harmed if they speak against injustices in which their colleagues and institutions are complicit. And institutional leaders are wary of upsetting the philanthropists upon whom their personal careers and fundraising goals depend. These fears are particularly potent now, when criticizing the Israeli state is falsely equated with antisemitism and billionaire donors have been publicly attacking individuals and institutions that do not repress pro-Palestinian speech to the degree they demand.

A third and arguably most fundamental contributor is the long-standing racism that underpins the US medical profession’s opposition to anti-apartheid protests. The AMA consistently supported segregated hospital care and the exclusion of Black doctors, only apologizing for this in 2008. Internationally, the AMA’s advocacy for the readmission of the apartheid-era Medical Association of South Africa (MASA) to the World Medical Association (WMA) provides an especially relevant historical example.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →MASA withdrew from the WMA in 1976 in response to a growing academic boycott against apartheid. The following year, South African physicians were complicit in the state torture and murder of Steve Biko—a medical student, anti-apartheid activist, and founder of the Black Consciousness Movement. MASA refused to address its members’ roles in Biko’s murder and in broader abuses within apartheid medicine.

As movements to boycott, divest from, and sanction apartheid South Africa grew across university campuses in the 1980s, the US medical establishment was not only absent from the effort to end apartheid; it operated in direct opposition to it. The AMA launched a campaign to readmit MASA to the WMA, using its disproportionate control over WMA votes to do so in 1981. The BDS movement against apartheid in South Africa, which was widely led by students, nonetheless persisted until it realized its goal. It is today universally celebrated, including in US medical schools, as one of history’s most important international movements against state violence and racial injustice.

The professed goal of medicine and public health is to protect life. But the histories of our fields are littered with shameful acts and long-standing norms that contravene what we nonetheless continue to claim are our most elementary ethical principles. Nazi medicine emerged from within the ranks of mainstream German organized medicine, for example, and many of its most repugnant ideas drew on racist theories and practices developed within US medicine.

We are now again at a defining historical moment as individuals, as a US medical profession, and as a society writ large. There is no ethical possibility of neutrality. We must make a choice: Will we continue to allow the same kind of forces that once endorsed US segregation and South African apartheid to determine our future and collective professional identity, or will we instead refuse ongoing complicity with the violence in Gaza and demand that our field use its authority to insist on an end to support for Israeli occupation and genocide?

Historical reflection by itself is not a moral achievement; separated from meaningful action in the present, it can even be used as an alibi for ethical non-accountability and complicity with violence, including genocide. Genuine ethics requires taking responsibility to use whatever means one possesses to stop violence and injustice right now.

Palestinians in Gaza will be provided little solace by confessional reflections after they have been killed either by bombs or starvation. We urge American medicine’s institutional leaders to immediately embrace our shared ethical obligations to protect life and the health workers charged with preserving it. We must condemn genocide and do all we can to stop it.

More from The Nation

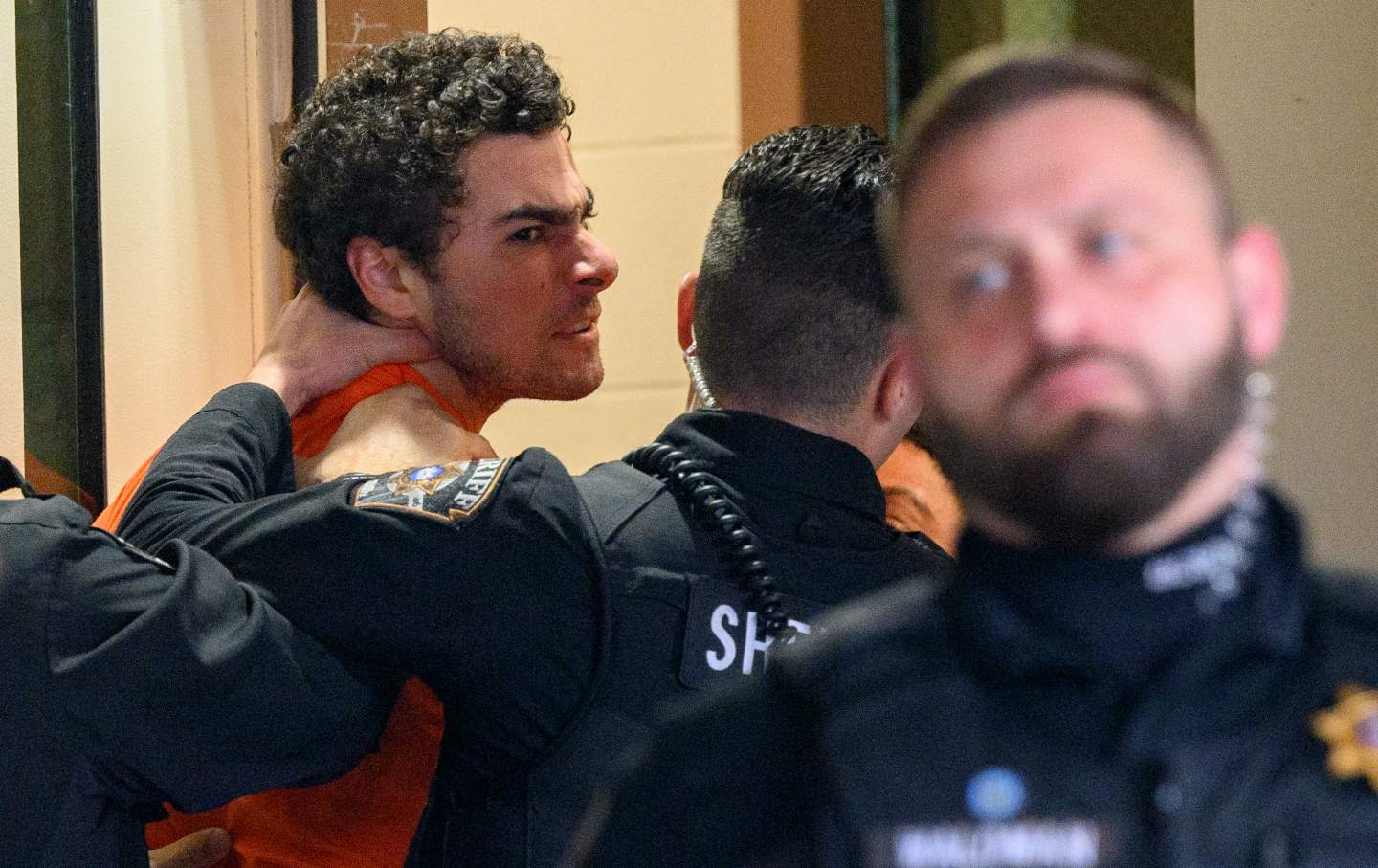

What Luigi Mangione and Daniel Penny Are Telling Us About America What Luigi Mangione and Daniel Penny Are Telling Us About America

When social structures corrode, as they are doing now, they trigger desperate deeds like Mangione’s, and rightist vigilantes like Penny.

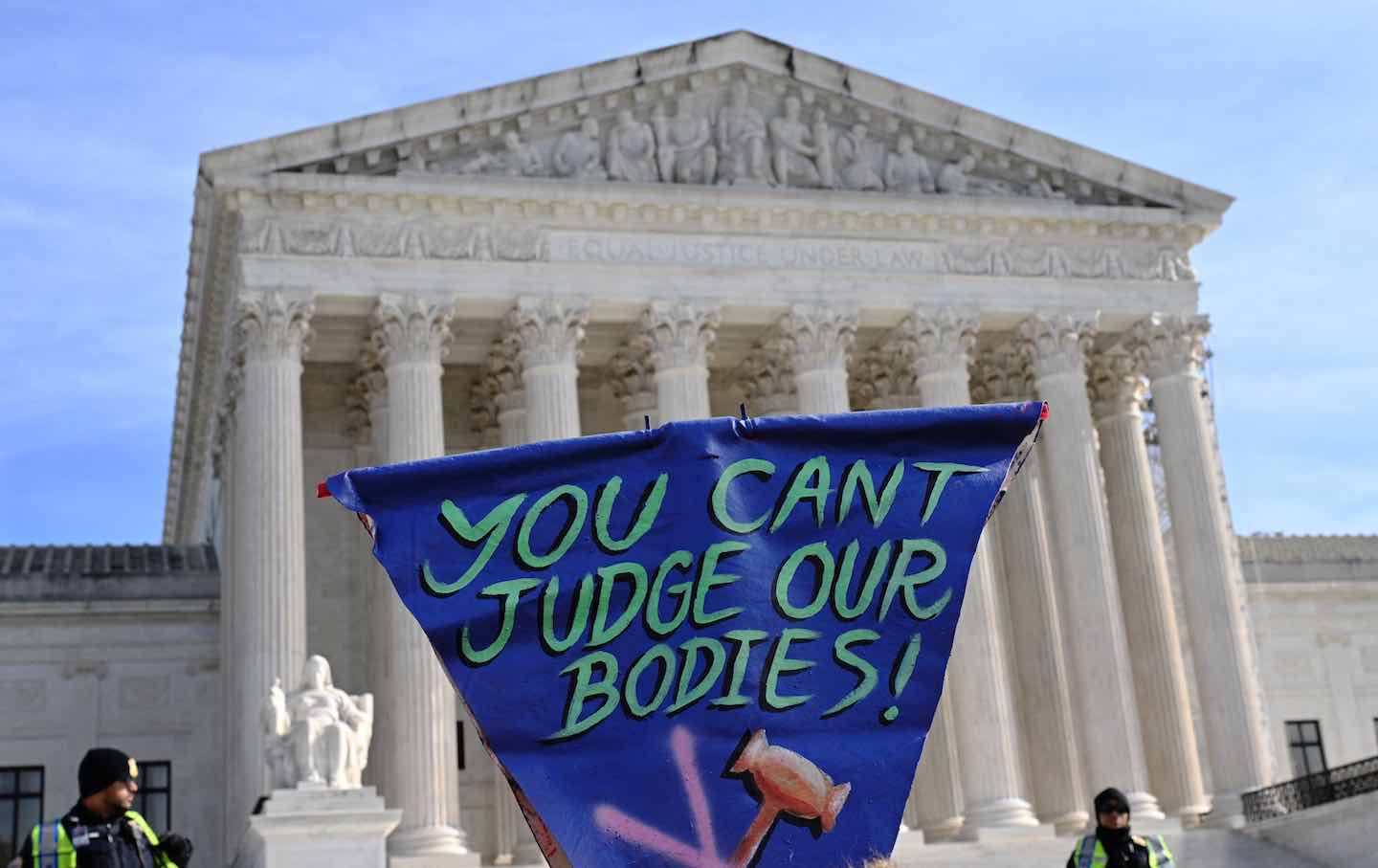

Banning Trans Health Care Puts Young People at Risk of Harm Banning Trans Health Care Puts Young People at Risk of Harm

Contrary to what conservative lawmakers argue, the Supreme Court will increase risks by upholding state bans on gender-affirming care.

It’s Still Not Too Late for Biden to Deliver Debt Relief It’s Still Not Too Late for Biden to Deliver Debt Relief

Four years after hearing the president promise bold action on student debt, most borrowers are still no better off, and many—especially defrauded debtors—are measurably worse off....

It’s Been a Tough Year. Let’s Help Each Other Out. It’s Been a Tough Year. Let’s Help Each Other Out.

There may be a dark shadow hanging over this year’s holiday season, but there are still ways to give to those in need.

Prison Journalism Is Having a Renaissance. Rahsaan Thomas Is One of Its Champions. Prison Journalism Is Having a Renaissance. Rahsaan Thomas Is One of Its Champions.

Thomas and his colleagues at Empowerment Avenue are subverting the established narrative that prisoners are only subjects or sources, never authors of their own experience.

Luigi Mangione Is America Whether We Like It or Not Luigi Mangione Is America Whether We Like It or Not

While very few Americans would sincerely advocate killing insurance executives, tens of millions have likely joked that they want to. There’s a clear reason why.