EDITOR’S NOTE:

Correction: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that the Dayton Memorial Library moved all books targeted by Ruffcorn's group out of the children's section. The library refiled all young adult nonfiction books into the adult nonfiction section.

The Small-Town Library That Became a Culture War Battleground

Throughout the country, far-right groups are trying to control what books kids can read. In Dayton, Wash., they tried to shut down the library altogether.

Illustration by Ross MacDonald.

Deprecated: Non-static method Athletics\TheNation\ACFBlocks::parse_popular_posts() should not be called statically in /code/wp-content/themes/thenation-2023/inc/single_article_functions.php on line 566

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

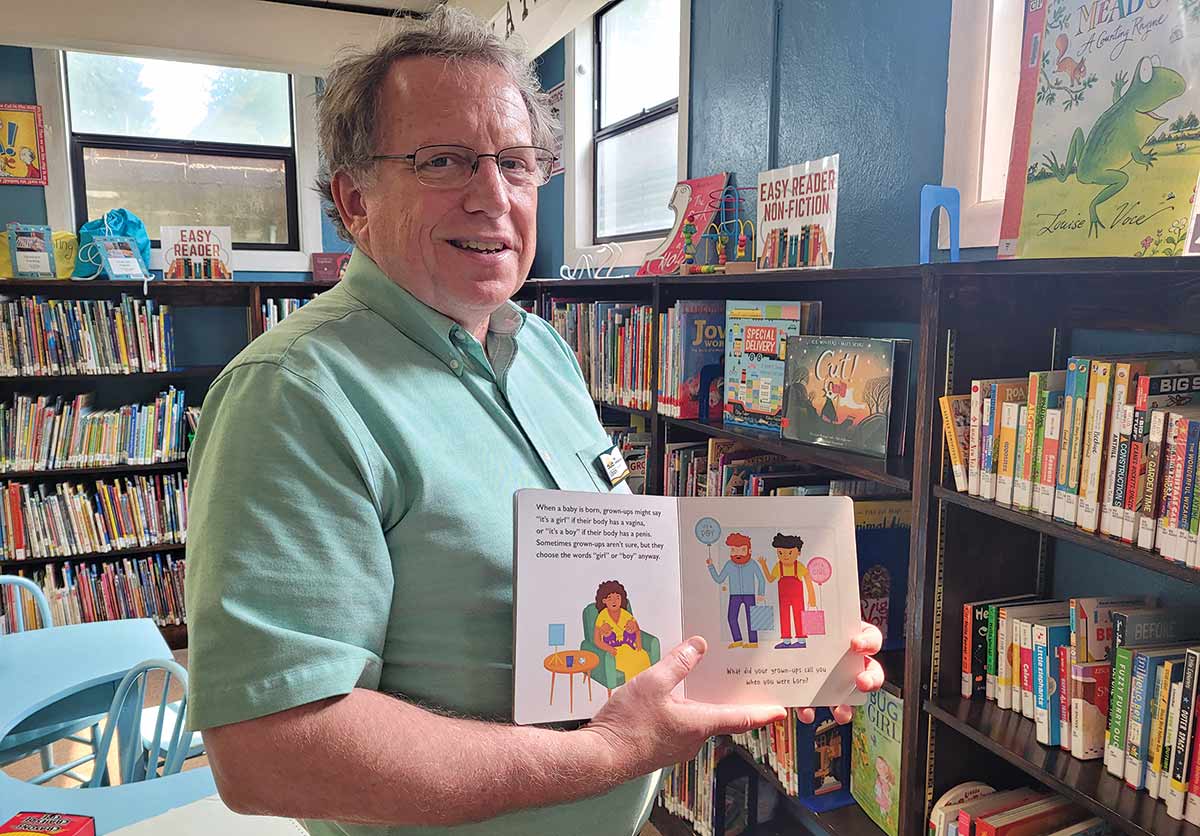

Dayton, Wash.—Todd Vandenbark stands at a table in the Dayton Memorial Library and spreads out a cluster of books. All are aimed at children and young adults, with titles such as What’s the T?, Gender Queer, This Book Is Anti-Racist, and When They Call You a Terrorist: A Black Lives Matter Memoir. They focus on race relations or issues of sexuality and gender identity and include titles that were bought to help celebrate Pride Month or Black History Month. Some are cardboard books, usually housed on the basement shelves that form the young children’s section. They include Being You, Our Skin, and Yes! No!, which explore issues of sexuality and consent in a way that kids who are still learning to read might understand.

Over the past couple of years, movements that seek to ban books with LGBTQ+ or racial justice themes have picked up steam in GOP-controlled states around the country. Pro-censorship groups have sprung up at both the local and national levels, pioneered by a Florida outfit with the Orwellian appellation Moms for Liberty. The organization is endorsed by Steve Bannon, the Heritage Foundation, and other avatars of the hard right and has more than 200 local chapters. Egged on by such groups, legislatures in Texas, Florida, Oklahoma, Idaho, Indiana, and other states have either passed or are considering policies restricting what sorts of books can be on school library shelves or lent to children from public libraries. The tiny town of Dayton is one of the latest flash points of this effort to limit what young readers can access.

Dayton is in the heart of southeastern Washington’s farm country, nearly 300 miles from Seattle, 125 miles from Spokane, and 270 miles from Portland, Ore., making it about as far from the region’s big cities as it is possible to be. The little town’s Main Street is lined with old stores and cafes, including a drugstore that still has its original soda fountain. The overwhelming majority of its residents are white, and most are conservative; in recent elections, upwards of 70 percent of the county voted for GOP candidates.

In the early 19th century, Lewis and Clark’s expedition traveled through this region. More than half a century later, following the routes of the new cross-country railroads, pioneers began settling small communities like Dayton, which was founded in 1871. By the early 20th century, townsfolk and nearby farmers, many of them growing apples and Bartlett pears on the sprawling orchards that drew water from the Touchet River, were pitching in for a fund to create a library, selling baked goods and scrap metal to raise money. In the 1930s, then-Governor Clarence Daniel Martin reputedly donated $5,000 of his own money to the library fund. And in 1937, in the heart of the Great Depression, WPA crews finally made that hope a reality, building the little brick library on South Third Street where Todd Vandenbark became the director in early 2021. That federal investment in local literacy—the sort of investment fiercely opposed by much of the right today—gave the out-of-the-way community access to a collection of books that could never have been matched by any of the town’s private individuals.

For the better part of a century, the library was run by the small town—Dayton’s population, even today, is only around 2,500 people—and offered free borrowing privileges to all Columbia County residents. But in the early 2000s, when the library faced insolvency, three-quarters of the county’s voters chose to establish a library district that would tax all county residents so that the library could survive and flourish.

But now the library is under attack. Would-be censors were marshaled on Facebook by a young mother of two—and a onetime library worker in the nearby townlet of Prescott—named Jessica Ruffcorn. Motivated by religious and political objections to the content of certain books, Ruffcorn and her followers are demanding that the “offensive” materials be removed from the children’s section and placed on the highest shelves in the adult section, preferably with warning labels pasted onto their covers. The effort began with a hit list of a handful of books, which soon grew to a dozen. At last count, the number exceeded 100 volumes. According to a representative of Moms for Liberty, the group has no chapter in the area and is not involved in the campaign, but many of these titles have also been identified by Moms for Liberty as being particularly objectionable.

When Vandenbark and his colleagues, backed up by the library’s five-member board of trustees, refused to cave to Ruffcorn’s demands, the group went for the nuclear option, circulating a petition to put a measure on this year’s November ballot to dissolve the library system altogether. If it succeeds, the community will lose its library and all of the services that the institution offers to residents in the town and the surrounding rural county—a stark small-town example of the changes a growing movement is trying to make across America.

Moms for Liberty, which has become notorious for targeting libraries, originated during the pandemic, when it focused on fighting mask mandates, school closures, and, in the wake of the 2020 George Floyd racial justice protests, anything that could be labeled “critical race theory.” In the years since, using the rhetoric of “parental rights,” it has spearheaded the growing opposition to the discussion of gender and sexuality in the classroom, mobilizing campaigns to remove books with gay and transgender themes from school libraries and from children’s sections of public libraries. It claims to have members representing all races and political leanings, including at least some members of the gay community who share its objections to the content of books such as Gender Queer, with its explicit illustrations of sexual acts, and This Book Is Gay, which makes reference to the hook-up app Grindr—prompting some critics to claim that the book serves to encourage teenagers who might want to use the app to seek out sexual encounters.

“We want to make sure the library books aren’t violating state statutes,” says Tia Bess, an African American mother of three from Florida’s Clay County who is Moms for Liberty’s national director of engagement. “If you look at the Florida state statutes, it describes what is obscene—genitalia being exposed.” Bess, who identifies as a lesbian and lives in what she calls a “two-mom” household, says she doesn’t care whom adults decide to sleep with. She does, however, believe that there is a threat of “hyper-sexualization” of young children from books with graphic content.

“The images are not blocked out,” Bess says, referring to the scenes in Gender Queer depicting fellatio and masturbation. “That’s pornographic. It’s not educational to learn how to perform a blow job at 12 years old, or how to insert your fingers in a vagina. That’s not educational. Our kids can’t even tell time on a regular clock, and two-thirds of kids can’t read at grade level. We need to go back to reading, writing, and math.”

For Amy Rosenberg, a trained librarian and member of the Dayton-based group Neighbors United for Progress, which was formed last year to push back against the attacks on the library and other conservative initiatives, this is a disingenuous argument. Yes, of course kids should be taught the basics in schools, but she also believes they should be allowed to read books that might be outside their parents’ comfort zone, even if others find those books to be in dubious taste. When Rosenberg was a librarian, she recalls, laughing, she would routinely stock books that she found offensive—such as children’s books by Rush Limbaugh—because patrons had requested them or shown an interest in them. That was, she said, the give-and-take of any library—a kind of freedom represented by the institution that is now under threat in the name of “liberty.”

“There’s an outrage machine in the country, and it’s continually putting fuel in and throwing things against the wall and seeing what sticks,” Rosenberg says over a beer in the garden of a little pub on Main Street. “Perceived obscenity always sticks. I don’t understand the correlation between books on a shelf and harming or grooming children. It doesn’t make sense to me—but it sure seems to resonate.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

And resonate it has. In the name of “parental rights,” closet doors that have been painstakingly pushed open over the past 60 years are now being slammed shut again in communities across America. Conservative political leaders in Florida, Texas, and other red states have vied with one another to sign the most restrictive laws against doctors providing medical care to the transgender community, libraries lending books with “gay” themes to minors, schoolteachers discussing issues of sexuality and gender identity with students, and schools teaching “critical race theory.” Conservative counties in Washington, Idaho, Michigan, and elsewhere have taken up the cry at the local level, seeking to punish librarians and teachers who make “offensive” materials available. Late last year, the American Library Association calculated that in the first eight months of 2022, 681 libraries had faced efforts to restrict book access, with 1,651 books challenged during that period. Now that state legislators, and governors such as Florida’s Ron DeSantis and Texas’s Greg Abbott, are stampeding to join this game, 2023 will almost certainly end up with even higher numbers.

Moms for Liberty has eagerly ridden this wave, going well beyond objecting to a handful of provocative books. The organization has built up a formidable political machine that seeks to push school boards and local governments to the right across a range of issues. It has sought to broaden the definitions of “harmful” material and to create enough anxiety among librarians and schoolteachers that they end up pulling controversial books of their own accord.

The organization’s online publicity materials speak of a conspiracy “to psychologically manipulate students to accept the progressive ideology that supports gender fluidity, sexual preference exploration, and systemic oppression.” It has endorsed hundreds of school board candidates, many of whom have gone on to win and then push local education policies in a more conservative direction. The group’s meetings are rapidly becoming as much a part of the political circuit for GOP candidates with national ambitions, including Ron DeSantis, as those of the NRA or CPAC. Hundreds of Moms for Liberty chapters have been seeded around the country, with members asked to sign a pledge to “honor the fundamental rights of parents including, but not limited to, the right to direct the education, medical care, and moral upbringing of their children.” Once they sign on, they are described by the group as “joyful warriors.”

This spring, the Southern Poverty Law Center categorized Moms for Liberty as an extremist group, describing it as “a far-right organization that engages in anti-student inclusion activities.” Despite that kind of designation—or maybe because of it—Moms for Liberty’s rhetoric is now firmly center stage, and Bess dismisses the SPLC’s censure as “intimidation tactics and scare tactics.” As she puts it, “I’m far from white, 5-feet-2, brown skin, been Black my entire life. Why would you put me on a list with the KKK?”

Despite the First Amendment’s protections of free speech and free expression, the United States has a long and inglorious history of book burning and idea banning. Take the Espionage Act, which allowed the postmaster general to deny mailing privileges to radical magazines and newspapers during and after World War I, or the Scopes Monkey Trial, or the bonfires of Beatles albums in the Deep South. James Joyce’s Ulysses, D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover, and William S. Burroughs’s Naked Lunch, among other now-canonical works of literature, were all for a time either banned or published in expurgated editions.

Movements from across the political spectrum have, at times, reached for the tools of censorship. These days, the far right has hit lists of books, and, for different reasons, so do some on the other side of the political arena. In the UK, Roald Dahl’s publishers rewrote sections of his works to remove language that might cause offense to contemporary readers. In the US, certain books by Dr. Seuss have been removed from public libraries because they have illustrations that look like ethnic stereotypes. Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn has been subject to campaigns to eliminate it from curriculums for its use of racist language. US publishing houses have hired “sensitivity” readers to make sure writers don’t step outside their lanes by writing about scenes and lead characters with racial and cultural backgrounds that are different from those of the authors. At least one well-known young adult fiction writer postponed publication of her work after being accused of cultural insensitivity, and many other authors have reported feeling intimidated by the process. On social media, a single reader’s objection to a book can explode into widespread denunciation, harassment, or “canceling” of the author, a pattern that does not go unnoticed by decision-makers in the industry.

In the 2020s, with the country riven by political and cultural conflicts, libraries find themselves navigating a minefield of competing demands. But these campaigns aren’t all equivalent. Efforts on the left to alter or restrict access to books or authors are not backed up by major legislative efforts or by the voices of powerful elected officials. Censorship from the right, by contrast, as pushed by groups such as Moms for Liberty, now has a vast political infrastructure behind it, its goals central to the political identities of rising stars such as DeSantis and Georgia Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene. As a result, it is far more dangerous, capable of long-term cultural damage, and well-positioned to further marginalize vulnerable people. The campaign to disappear the stories and experiences of gay or transgender Americans doesn’t stop with books, either: Some members of Moms for Liberty, according to the website Pinknews, have openly called for LGBTQ+ kids to be educated in separate classrooms from other students.

Regina Weldert is a 72-year-old transgender resident of Dayton who transitioned in her 60s, shortly after she retired from her job as a fish biologist and started a coffee roasting company in town. “I retired on September 30, and on October 1, I showed up as Regina, and I’ve never been anything other than that since then,” she says, her white hair cascading over her shoulders and her toenails painted a brilliant red. There’s a real risk, Weldert believes, that censoring books on the LGBTQ+ experience could harm the very children people like Ruffcorn claim to be protecting. “It gets to the point where we’re not protecting children and are creating a lot of animosity and discomfort for children who need guidance on sexual orientation,” she says. “If we don’t allow them to learn, the alternative is they run away from home and become alcoholics or drug addicts or sex workers. Or they commit suicide.”

Vandenbark thought so too, which was part of the reason he had fought so hard to keep the books available in the children’s section of the library. It was a position that infuriated his opponents. Ruffcorn posted a lengthy screed on Facebook dismissing Vandenbark’s concerns as “some phsyco [sic] babble about the rise in LGTBQ+ [sic] population especially a rise in our youth and how they are more likely to commit suicide.” But the numbers back Vandenbark up. In 2022, the Trevor Project, a crisis intervention and suicide prevention organization for the LGBTQ+ community, estimated that 28 percent of LGBTQ+ youths had reported being homeless at some point in their lives. In 2015, the US Transgender Survey found that more than half of transgender youths who had experienced multiple instances of discrimination or violence in the past year had attempted to kill themselves.

In all the years she has lived in Dayton, Weldert tells me, she has never faced trouble based on her gender. In fact, it is when she visits the big cities on the coast that she has been subject to threats and intimidation. Now, however, the library battle is bringing ancient prejudices to the surface once more. “It makes me feel like even though people say I’m safe, I’m not sure that I am,” she says. “From the rhetoric at these meetings, why would I feel safe? It’s uncomfortable. Maybe I should back off, stay at the house, and be afraid. But that’s not me. I’m going to come out and be visible.”

But whether Dayton’s children will get to read about people like Weldert in the future, by checking out books on the transgender experience at the local library, remains an open question.

With a receding hairline, a slight paunch, and a gentle speaking voice, Todd Vandenbark is an unlikely local hero. His Dayton library office is adorned with haphazard piles of folders, a stash of red Folgers instant coffee containers, and a number of electronic devices, including some providing Wi-Fi hot spots, that the library lends out to patrons. Yet circumstances have thrust the librarian to the front lines of Dayton’s culture war.

For more than a year, Vandenbark stood firm, refusing to remove or label the challenged books, even when the level of acrimony began to rise—including, as with many political crusades in recent years, on Facebook. One comment proclaimed that “The IDIOTS who are promoting this crap need to be in prison, or pushing daisies up from the roots.” Another called Vandenbark’s book choices a deliberate effort to desensitize and “groom” children. Offline, he faced down a group called Columbia County Conservatives (CCC), run by a former county commissioner and special forces operative named Chuck Amerein, which took a slightly different tack: While CCC’s members also opposed the content of the books that were being displayed in the kids’ section, their rhetoric tended to focus more on what they saw as the library’s waste of taxpayer dollars. This was in keeping with the group’s broader worldview: It has also opposed the building of a child care center—one member spoke out at a public meeting to say the service was unnecessary because women should stay at home and look after their kids—as well as a bike trail and a community center. (Amerein didn’t return phone messages asking him to comment for this story.)

Throughout this period, the library’s five-person board of trustees backed up Vandenbark, despite the recent appointment of a member of Columbia County Conservatives to the board by the conservative county commissioners. “Nothing got banned,” says Jay Ball, a book-loving auto mechanic who moved to Dayton in the early 2000s and is currently chair of the library board. “We’re in the middle of it. It’s not that much fun. But we stick with it.”

Elise Severe, a 36-year-old self-proclaimed “opinionated stay-at-home mother” who grew up on a wheat farm just outside town, isn’t taking any chances. Worried that the library board wouldn’t have the strength, in the long run, to stand up to a large community effort to defund the library or to stop the county’s rightward lurch, she set up a political action committee, Neighbors United for Progress. It’s made up of moderates from both political parties and has a mission to push back against Ruffcorn, Amerein, and other local agitators. NUP’s members have been putting forth alternatives to CCC’s positions at public hearings, educating residents about the dangers of Ruffcorn’s efforts, and recruiting slates of candidates to run for public office against hard-right candidates. The group’s chosen candidate for county commissioner, a moderate conservative named Jack Miller, defeated Amerein last year in the first of what they hope will be several electoral victories in the coming years. Severe has even convinced her parents, both of them moderately conservative by temperament, that restricting access to books and threatening to close the library is a bridge too far. As a mother herself, she remembers how much the library meant to her when she was young.

“I was always an avid reader,” Severe says. “I’d challenge myself to read the classics over the summer—Jane Eyre, Lady Chatterley’s Lover. I had this huge list that I was very proud to tick off. The best time to read was in the harvest field—it was hot, sunny, quiet.”

Unable to get the books removed from the children’s section, the objectors declared war on the library system itself, going door to door and gathering hundreds of signatures for a petition to place a vote on the November ballot to dissolve the entire library district. When I spoke to her on May 18, Ruffcorn said they were on the verge of securing the needed 300 signatures, and that she was confident the proposition would be on the ballot come November. “There are a lot of people upset about the books and budget, and a lot of people not happy with our director,” Ruffcorn said. “We’ve asked to have a few books moved and a policy to protect our kids. We’ve been shot down every time.”

If the referendum passes, the library will be defunded, its collection seized by the state and distributed to the state library, and a treasured local institution will bite the dust, a casualty of America’s take-no-prisoners culture wars. Yet Ruffcorn, a diminutive, soft-spoken young mother who homeschools her kids and heads the local Little League, doesn’t see her campaign as censorship, but rather as a fight for individual freedom: the right for parents to limit the flow of information to their children. To her and her Facebook followers, books about young people exploring their sexuality are simply pornography by another name. And allowing children to peruse these books in the library, especially those that validate gay and transgender feelings, makes librarians little better than pedophiles and groomers. Ruffcorn’s Facebook profile image carries the motto: “Let men be masculine again. Let women be feminine again. Let kids be innocent again.”

Standing on her front porch in a T-shirt reading “Adulting Requires Alcohol,” Ruffcorn argued that the books she had targeted “involved sexually explicit material, sexual material involving minors, abuse against minors,” as well as “racial topics—basically racist books.” Ruffcorn felt that placing these books at the eye level of young children exposes them to offensive ideas against their will and against the wishes of their parents. “My 8-year-old, looking for a dinosaur book, doesn’t need to come upon a sex book instead,” she says.

Ruffcorn’s actions have sparked a furor in Dayton, and even many conservatives there say she has gone too far. “I’m a conservative Christian. I’ve been in church leadership for 20 years,” says Tanya Patton, a special-education teacher who led the campaign to create the library district nearly 20 years ago. But, she says, “I support 100 percent the freedom to read. I believe passionately in libraries and the value of libraries.” In a town as small and remote as Dayton, the library provides benefits to its residents that would otherwise remain lacking. In the information age, libraries function as much more than places to borrow books—they provide access to computers, public space, and various social services.

“It doesn’t make sense to me,” Patton says. “I have the right to take the books out or not take them out. If there’s a movie on TV, I have the right to watch it or not watch it. But I don’t have the right to tell others what to watch or read. It doesn’t seem right to me that one person or group of people is making moral or ethical judgments about certain content and saying it needs to be singled out and labeled as dangerous.” Moreover, she says, the whole thing is a red herring: If kids want to find certain material, all they have to do these days is whip out their smartphones. To Patton’s mind, removing books from libraries simply makes them desirable contraband.

In mid-June, Ruffcorn turned in 16 pages of signatures to the county courthouse for verification. She told me that she put the odds of the measure passing at about 50/50. But by that time, the local prosecutor had sent a letter to the state attorney general asking for an informal opinion on whether the dissolution petition was constitutional. There was a strong legal argument to be made against putting such a measure on the ballot in the first place. In another twist, the attorney general concluded that because of an obscure provision in the state Constitution regarding rural library districts, only residents of the unincorporated part of the county would get to vote on the measure; Dayton’s residents, bizarrely, would have no say. That was yet another reason why opponents hoped that their own attorney would be able to persuade a judge to block the initiative.

As it turned out, days after Ruffcorn submitted her petition, the court ruled that a majority of the signatures were illegitimate, leaving her campaign a handful of signatures short of what it needed. The rules stipulated that she would have to start from scratch, gathering all of the signatures all over again.

But the petition itself wasn’t the only cause for alarm. It’s likely that the conservative three-person Board of County Commissioners will, in the coming years, continue to appoint people to the library’s board who reflect the values of Ruffcorn and her fellow petitioners. In other words, Ruffcorn could lose in November and yet still ultimately come out on top, setting a precedent in which a few angry citizens would get to dictate to librarians which books should carry warning labels, or be relegated to the top shelf of the adult section, or require parental approval for a child to check out.

Ruffcorn wasn’t concerned about the resources that would be lost if the library were dissolved. In fact, she questioned the value of the institution altogether. “I think libraries in this digital world are becoming less and less of a priority,” she told me. “We have enough resources in this town to make up some of the losses. The way our library is being run doesn’t make it an asset any longer. From the people I’ve talked to, they don’t really use it. Nobody attends the classes. Nobody goes to the teen events or the computer classes. It’s a very small group that go to the story hour. The librarian has pushed people away; they don’t think it’s a safe space anymore.”

In spite of Ruffcorn’s claim to speak for the broader community, her disregard for the library was hardly unanimously embraced—even among those who otherwise shared her values. “Dayton is a small-town, good-old-boy place, where certain things are not accepted,” one very religious, very conservative worker at the local drugstore told me. But she couldn’t get on board with the anti-library effort. “It would be very detrimental to our community if the library were to be closed,” she said. “I was at the library today, printing some papers on my lunch hour, and I got a movie. That’s how I spent my lunchtime.”

Similar library-defunding battles are now unfolding all over the country, including just across the state line in Meridian, Idaho. The Meridian library system—made up of five locations, a Bookmobile, and a couple of trucks that deliver books to homes and senior centers—is orders of magnitude larger than Dayton’s. It has nearly 200,000 volumes on its shelves, and each year more than 1.3 million items are checked out by the 54,000-plus card-carrying library members.

Last year, a group called Concerned Citizens of Meridian began encouraging its members to attend library board meetings. They presented lists of books that they said needed to be either removed from the library or cordoned off—much as pornographic videos used to be restricted to adults-only sections in video rental stores. When the librarians and trustees responded that they wouldn’t enforce censorship, CCM returned with a petition urging the Ada County commissioners to put a library dissolution vote on the ballot later this year. Two lengthy and sometimes heated meetings drew hundreds of residents—most of them infuriated at the prospect of losing their library over 56 challenged books—who spilled out into the overflow rooms and then beyond. In late March, the commissioners declined to put library dissolution on the ballot.

That wasn’t, however, the end of the matter. In early 2022, members of the Idaho House of Representatives had passed a bill, HB 666, that would have made it possible to prosecute people who distributed “obscene” materials—a term so vague that even the US Supreme Court has struggled to define it. The bill died in the state Senate. This year, however, in the wake of the Meridian controversy, a similar, more politically palatable bill was introduced during the three-month legislative session. The new bill, HB 314, would have allowed private citizens to sue librarians and teachers for $2,500 each time they were found to have made “obscene” literature available to children. It passed in both chambers, but in the face of a furious reaction from librarians, educators, and civil rights groups, the bill was eventually vetoed by the governor. Yet supporters of the legislation are keen to reintroduce it in 2024. If some version of the bill passes, it will essentially do for Ada County and its libraries what the CCM failed to achieve, making it all but impossible to stock books deemed “offensive” by small but vocal factions.

In late June, Moms for Liberty held its annual summit in Philadelphia. Ron DeSantis and Donald Trump both attended as speakers, as did several other GOP presidential hopefuls. Not surprisingly, the event was a smorgasbord of misinformation. Trump claimed that former Virginia governor Ralph Northam wanted to give mothers permission to kill their newborns and that President Biden had personally had Trump arrested on false charges. DeSantis wrongly stated that parents in California who oppose gender-affirming surgeries for their pubescent children risk losing custody of them, and he took yet another swipe at “critical race theory” as intrinsically anti-American. That so many Republican presidential hopefuls have chosen to cast their lot with an organization that has made censorship mainstream again speaks volumes.

Back in Dayton, the local government could well be headed in the same direction. Two of the five members of the library’s board of trustees are solidly in the conservative camp; next April, the term of office for another member will end. When the conservative county commissioners replace that member, it’s entirely possible the board will have a majority less inclined to defend the library’s choice of books on First Amendment grounds.

Perhaps sensing that the writing was on the wall, Todd Vandenbark announced in mid-June that he would resign as library director, effective the following month. He was, he told his supporters, simply fed up with all the vitriol directed at him. He would be moving on to another job in another city, but, not wanting the harassment to follow him from Dayton, he refused to disclose where he would be moving or what the job entailed.

“Despite the encouragement and support of so many of the good townspeople here, it’s become too uncomfortable to continue working here,” he told me on a telephone call the next morning. He was hoping to make new friends and put down new roots, but he had no plans to ever visit Dayton again. “I worked hard to defend the First Amendment,” he said, “and now it’s someone else’s turn.”

Elise Severe, of Neighbors United for Progress, was devastated by the news. “He doesn’t even feel comfortable telling where he’s going,” she said. “I cannot believe how mean and hateful people are to each other. To react and target a single person, it’s beyond…” She stopped, momentarily at a loss for words. Then she continued: “They openly posted ‘pedophile,’ ‘groomer,’ ‘porn-pusher.’ They accomplished what they wanted. They ran a man out of town.”

Jessica Ruffcorn reacted more succinctly. On a Facebook page called “Dayton Speak Freely,” she posted a GIF showing people waving happily. “Bye, Bye, Bye,” it read.

A month later, the new interim library director made the decision to move all young adult nonfiction books to the adult section, with the result that some of the books Ruffcorn’s group had targeted were removed out of the children’s section. It was, Ruffcorn announced in a public comment at a library board meeting in mid-July, “an amazing, positive step forward.” Nevertheless, she added, if the signatures to put a dissolution measure on the ballot ended up being validated, the vote would still go forward come November. To assuage her distrust, she said, the library would have to promise not to move the books back after November or buy more books on the same controversial themes. She also wanted the library to break away from the American Library Association and demanded that Jay Ball resign from the board. On July 21, Ruffcorn submitted her new petition to the county auditor’s office, and a few days later, it was certified as sufficient.

Even if the library isn’t ultimately dissolved, Ruffcorn’s group has already flexed its muscle. They have shown that if the new director gives them an inch, they will take a mile. As a result, whoever succeeds Vandenbark in the long run will almost certainly think twice before stirring that hornet’s nest again.

Correction: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that the Dayton Memorial Library moved all books targeted by Ruffcorn’s group out of the children’s section. The library refiled all young adult nonfiction books into the adult nonfiction section.