One afternoon in mid-march, Jeremy Kaiser sat behind his corner desk at the Scott County Juvenile Detention Center. Kaiser, the director of the facility, excitedly held up a piece of yellow paper. On it he’d written a list of the people most vocally opposed to the county’s plan to build a new, bigger detention center.

“I put a little check mark by them every time they show up” at marches or the county board of supervisors’ meetings, he said.

The next meeting, at which the board would vote on the detention center’s budget, was scheduled for the following night. It would determine the fate of the facility for 10-to-17-year-olds awaiting trial or placement in a rehabilitation program.

Kaiser, who has a muscular build and closely cropped brown hair, is the zealous face of the $21.75 million plan. Drafted in 2018, it was designed to replace an 18-bed juvenile detention center that many residents and advocacy groups agreed was outdated. But the need for a new facility was the only thing on which people agreed. When it was decided that the new jail should hold 40 beds—far more than what many felt was justified in a county that already jailed more young Black people than anywhere else in the state—the opposition grew. And when officials began to consider using $7.25 million of the $33.5 million the county received in Covid-19 relief to help fund the expansion, so did people’s outrage.

There was a groundswell of opposition from residents and advocacy organizations, who maintained that the federal funds should instead be spent on affordable housing, health care, food security, and stimulus checks for undocumented workers.

“That’s where the money, that’s where the focus…should be at, as opposed to trying to build a jail to continue to put kids in jail, to try to arrest our way out of a situation,” said Michael Guster, the president of the Davenport chapter of the NAACP.

“They choose to be blind and deaf to what we’re saying as a community and what our needs are,” said Gloria Mancilla, a Davenport resident who has urged the county to allocate funds for undocumented workers.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

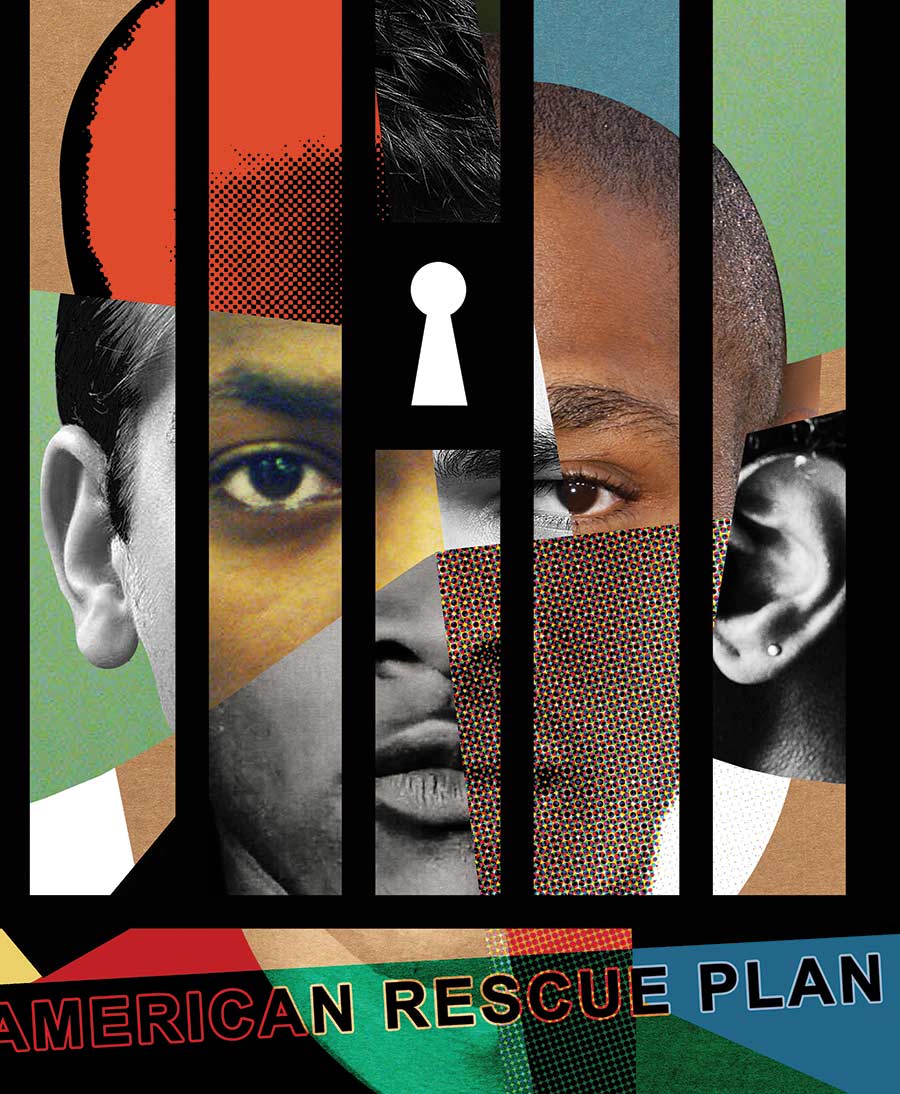

Throughout the country, counties are dipping into funds from the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) and the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act to build and expand jails and prisons. At least 20 counties in 18 states are using, or want to use, Covid relief money this way. The problem is, their decision to do so violates the spirit, and likely the letter, of the rules governing how relief money can be used. These rules, finalized by the US Treasury earlier this year, ban jurisdictions from using Covid relief money to build or expand correctional facilities. Yet that hasn’t stopped local officials in a number of counties from pushing their projects through, spending their ARPA and CARES Act windfalls like winning lottery tickets for long-sought expansions.

“The arrival of ARPA funds has provided an easy way out for counties that previously were having a hard time justifying spending tens of millions of taxpayer dollars on [building] jails,” said Wanda Bertram, a communications strategist at Prison Policy, a nonprofit research center.

In Scott County, the push to use this money to expand a jail for children is happening at a time when the number of juvenile arrests nationwide has fallen 67 percent since 2006 and reached a new low in 2019, according to the Justice Department. Yet even as the overall numbers have been falling, the system remains as unequal as ever, with Black and brown people filling cells at disproportionately high rates.

Iowa, for instance, which incarcerates children at rates higher than the national average, ranks eighth in the US for racial disparities in the incarceration of young people, according to a 2021 analysis by the Sentencing Project, a research and advocacy organization. And within the state, those opposed to the new jail argue, Scott County is responsible for some of the worst racial disparities. “Black youth are 8.7 times more likely than white youth to be incarcerated here,” Marcy Mistrett, the former director of youth and justice at the Sentencing Project, told attendees at a 2021 panel discussion on the juvenile detention center plan. “In Scott County, this means one out of every 22 Black kids gets detained versus one out of every 457 white children.”

“I want to spend every one of those ARPA dollars,” said Ken Croken, the only person on the five-member board of supervisors to oppose funding the new jail with relief money, in an interview with The Nation before the vote took place. “I just don’t want to spend it subsidizing an abusive and racist criminal justice system.”

Scott County, on the state’s eastern border, is the third-most-populous county in Iowa. Nearly two-thirds of its population, or 101,000 people, live in Davenport, a once-bustling manufacturing hub that had been lined with flour, wool, and saw mills powered by the Mississippi River’s waters. A majority of the county’s wealthier, mostly white families live on the nearly 1,000 farms that crisscross the county. Most of the county’s Black residents—who account for 8 percent of the population—live in either downtown Davenport or the lower-income neighborhoods in the West End.

The juvenile detention center, a one-story brick building constructed in the 1970s as a car dealership, sits near the adult jail and the county administrative services building. The facility’s size wasn’t an issue until 2018, Kaiser said, when the average daily population of detained children climbed to 31, up from 16 in 2017. This was the result of a combination of factors, including court backlogs caused by an increase in car thefts and diminished capacities at rehabilitation centers that left children waiting for open beds, according to the county’s annual report. This surge, however, was short-lived: The detention center’s average daily population fell to 21 in 2020 and to 18 in 2021. In a sign that the trend is continuing, the average daily population was 13 during the first half of this year.

Kaiser, who emphasized that the new jail would also offer treatment and rehabilitation services, cautioned the board of supervisors that the old facility would soon become overwhelmed. “I started ringing alarm bells,” he said.

In the summer of 2018, county officials agreed to explore the idea of building a new jail, which was to be rebranded as the Youth Justice & Rehabilitation Center. They convened a committee to make a recommendation on size, with the majority of its participants involved in either law enforcement, the courts, or jail construction. The committee recommended that the jail contain 40 beds to ensure that the county would not need to add more in the future and to prevent children from being sent out of the county to other facilities should there be an overflow.

“I felt like I was tricked,” said committee member Rev. Melvin Grimes, the executive director of Churches United of the Quad Cities Area. (Quad Cities encompasses cities and counties in Iowa and Illinois.) Grimes, who opposes a 40-bed jail, added, “I felt like my place on the committee was [solely] so they could say, ‘We have some people here who are representative of community organizations.’”

“You don’t build a church for Christmas morning,” said Croken, who is not opposed to a new jail in principle but disapproves of its expanded size, referring to the committee’s decision. He pointed out that the county’s five-year daily average for detainees (from 2016 to 2021) was 22. (The Nation confirmed this number.) “You’ve got to work off averages and trends.”

In June 2021, the board of supervisors met to discuss financing. Listed on a slide as a potential funding source for the project was money the county was eligible to receive under ARPA.

Scott County received the first half of its $33.5 million in ARPA funds the following month. By the fall, officials had designated up to $7.25 million for the detention center project. Other high-priority projects included installing storm sewers, improving air circulation in the administration building and the adult jail, and promoting tourism. Providing $6 million for below-market-rate housing was listed as a “medium to high” priority. The board of supervisors—an elected panel of three Republicans and two Democrats, all of them white men—designated no money to stimulus checks for undocumented workers. The new detention center, officials said, met the county’s goal of “financially responsible government.”

One supervisor on the board, John Maxwell, a fifth-generation dairy and cattle farmer, called the project his No. 1 priority for federal dollars, citing the county’s four-year-long effort to build a new facility. “I am 100 percent supporting this, and I will ride it all the way,” he declared during a meeting last October.

“It certainly meets my smell test for the spirit and the nature of the funds being deployed here,” added another supervisor, Tony Knobbe, at the same meeting.

But 10 advocacy groups, including the Iowa–Nebraska NAACP and the ACLU of Iowa, called the county’s use of ARPA dollars unlawful. Citing US Treasury Department guidelines on the use of Covid relief funds, they wrote a letter to the board of supervisors this past February asking it to reconsider its plan.

“Scott County’s proposed use of ARPA funds to build a new, expanded juvenile detention center violates the express terms of Department of Treasury rules,” the letter stated. “Furthermore, building a new, expanded juvenile detention center is out of step with national and statewide juvenile justice trends and would exacerbate the existing racial inequities in the juvenile justice system.”

The Treasury rules, released in January, are broad yet specific. They state that the ARPA money given to states, counties, and tribal governments should be spent on recovering and rebounding from the pandemic and that eligible projects must fall into one of four categories—from pay for frontline workers to “capital expenditures that support an eligible Covid-19 public health or economic response,” which is the category under which Scott County had originally planned to build its jail project. While governments have flexibility within these categories, there is one explicit restriction in the capital expenditures category that is relevant to Scott County’s plans. “Treasury presumes that the following capital projects are generally ineligible: Construction of new correctional facilities as a response to an increase in rate of crime,” according to the department’s final rules.

Despite this requirement, Scott County has not halted its plans for a new juvenile jail. Instead, officials have sought money for the project under the “Replacing Lost Public Sector Revenue” category of the Treasury Department’s rules for ARPA funds. This category enables counties to claim a $10 million allowance for “general government services” to replace revenue lost during the pandemic. Scott County budget director David Farmer told the Quad-City Times earlier this year that he considers the juvenile detention center a “general service.”

This category is the “most flexible” in the program, according to the Treasury, and Scott County officials have interpreted it as permitting their jail expansion plans. That may be because this category doesn’t explicitly bar correctional facility projects from receiving funds; moreover, the ARPA rules state that a restriction in one category doesn’t necessarily translate into a restriction in another. County leaders have read this language as a license to move forward.

“It was vetted by the county attorney’s office,” Brinson Kinzer, another supervisor, said in an interview with The Nation. “[He] basically said it’s at the board’s discretion to use these funds.” (County Attorney Michael Walton did not respond to requests for comment.)

But the acting counsel for the Office of the Inspector General in the US Treasury, A.J. Altemus, disagreed with that analysis. In an e-mail to The Nation, he clarified that “general government services” funds cannot be used for jails. “Capital expenditure restrictions apply to the use of the $10 million for lost revenue,” he wrote.

He then referred The Nation to the overview of the final rules for ARPA funds, which states: “The use of the $10 million standard allowance for replacing public sector lost revenue must be consistent with use of funds requirements…. Treasury presumes that construction of new correctional facilities as a response to an increase in rate of crime is generally ineligible.”

There’s one more potential problem, perhaps more ethical than legal, with Scott County’s reliance on Covid relief funds for its new juvenile jail. The $10 million general services allowance is meant to replace revenue lost during the pandemic. While jurisdictions are not required to provide an accounting to the Treasury Department, it is also true that Scott County does not appear to have suffered much revenue loss during the pandemic. In an e-mail to The Nation, Farmer wrote that the county lost no revenue in 2020 and ended 2021 with more than $6 million in surplus funds. Indeed, those surplus funds are also going toward the detention center project, according to Farmer.

In the 16 months since Joe Biden signed ARPA, the federal government has distributed roughly $500 billion in Covid relief funds. Recipients are spending the money in a variety of ways. A February 2022 analysis published by the Brookings Institution found that large cities and counties were using the bulk of their funds to replace lost revenue, respond to the pandemic, and underwrite infrastructure projects.

But as in Scott County, a number of local governments, often skewing conservative, have embraced the relief money as an opportunity to expand their jails. The Washington County Jail in Fayetteville, Ark., for instance, has been one such beneficiary; the county is using $335,000 of its ARPA package to help fund an additional 230 beds. (It’s worth noting that just last year, the jail made headlines when prisoners with Covid-19 were treated, without their knowledge, with ivermectin, the antiparasitic medication that the Food and Drug Administration says has not proved to be effective in treating the coronavirus.) In Florida’s Pasco County, officials have authorized $20 million of ARPA funding for a project to add 478 beds to its jail. Coshocton County, Ohio, will more than double the size of its jail in a $28.4 million project that will use $3.15 million of CARES Act funding, according to documents obtained by The Nation.

These jail expansions come on the heels of successful decarceration campaigns that saw jail populations decrease by 26 percent during the first year of the pandemic. And while the number of filled jail beds has been creeping back up since courts resumed adjudicating cases last spring, criminal justice advocates say this doesn’t validate the use of relief money to increase the size of facilities.

“If we’re really going to think about rebounding from Covid, then the dollars should be spent on public health in these communities,” said Keesha Middlemass, a public policy professor at Howard University and a fellow at the Brookings Institution. At a minimum, she noted, counties should use Covid relief money on programs that address the causes of incarceration, such as food insecurity and a lack of jobs, affordable housing, or mental health treatment.

On the day of the Scott County Board of Supervisors’ budget vote for fiscal year 2023, which fell on St. Patrick’s Day, residents of the Heatherton Apartments in Davenport sat by their cars in camping chairs. Broken glass covered the parking lot; a discarded mattress stuck out of a blue dumpster. The city had ordered the residents of the complex to vacate their homes by the end of the month, because the landlord had failed to make repairs that would bring the buildings up to code.

Standing off to the side was Tonya Roberts, a mother of two young children. She wore a sapphire-blue hooded sweatshirt and a matching patterned head scarf. She’d looked at six apartments, she said, and had finally found a two-bedroom for $700 a month—$125 more than she was paying at the time. Roberts was working at McDonald’s, making roughly the minimum wage.

While county officials had designated $6 million in ARPA funds for housing— $1.25 million less than they proposed to spend on the jail expansion—Roberts said that wasn’t enough. “Why take that money [for the juvenile detention center] when you can take the money to put in these houses to help us?” she asked.

Later that night, the board of supervisors met to vote. As the board recited the Pledge of Allegiance, two dozen Latino workers and their allies stood in the back, holding blue-and-yellow signs that read “We are excluded and essential workers” and “Together we stand.” They had come to ask that some of the pandemic funds be designated for workers who had not received stimulus checks because of their undocumented status.

A dozen people spoke, asking the board to spend the Covid relief money to help people, not build a new jail.

The board voted 4–1 to approve the new budget, which included the use of $7.25 million in ARPA funds on the juvenile detention center. Croken was the lone holdout. (After the meeting, the board chairman, Ken Beck, said he couldn’t talk about his vote and did not reply to later requests for an interview.)

In a telephone call the following week, Pete McRoberts, the policy director at the ACLU of Iowa, said he was disappointed in the outcome of the vote. Shortly after, he followed through on the warning letter he and others had sent in February and reported Scott County to the Treasury, alleging that it was misusing funds.

“It seems that this county did not do their due diligence, as far as the totality of regulations,” McRoberts said. “We gave them everything that they needed in order to come to a lawful conclusion. And it’s very regrettable that they didn’t do it. So now it’s up to the Department of the Treasury and the inspector general.”