Why Bill Gates’s Philanthropy Is a Problem

If you learn to look past Gates’s PR halo, you will see his greed, hubris, and superiority complex.

Bill Gates speaks during a press conference announcing a a plan to increase awareness of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals.

(Toshifumi Kitamura / AFP / Getty)Thousands of news stories have profiled Bill Gates’s generosity over the last two decades. Essentially every day, headlines remind us of his private foundation’s largesse: a million dollars here, a billion dollars there. These are mind-bending sums for most of us—but they have also effectively short-circuited our brains. The one-sided storytelling about Gates’s selfless philanthropy has created a dangerous mythology that misunderstands who Bill Gates really is and what he is actually doing.

After two decades of philanthropic giving, Bill Gates continues to be one of richest people on the planet. He boasts a private fortune of $117 billion (and that’s after his costly divorce from Melinda, whose bank account today exceeds $10 billion). He also oversees the Gates Foundation’s $67 billion endowment. The combined $184 billion he controls surpasses the gross domestic product of virtually every poor nation in which the Gates Foundation works today.

A sober analysis of Gates shows he is just as worthy of the titles of hoarder and miser as he is philanthropist and mensch. Relative to his vast wealth, Gates is giving away a tiny amount of money—that he doesn’t need and that he could never possibly spend on himself. So the question is: Instead of celebrating the million-dollar gifts his foundation donates, why aren’t we interrogating the $184 billion that Gates isn’t giving away? Why aren’t we asking: How is it that the world’s most generous philanthropist is becoming richer and richer, year over year?

It’s the kind of contradiction that defines Gates, one of the most misunderstood people in the world. Much of what we know about Gates, or think we know, comes from Gates himself—from the research his foundation funds, the think tanks it sponsors, the journalism it underwrites, and the megaphone Gates has cranked up to 11. Arguably the most effective aspect of Gates’s philanthropic career has been its PR. And, arguably, the single biggest beneficiary of the Gates Foundation has been Bill Gates, himself.

The Gates Foundation ferociously claims that its “bottom line is the lives saved,” which Bill Gates also describes as his North Star. Asked by CNN in 2021 whether he would be joining fellow billionaires—Jeff Bezos, Richard Branson, and Elon Musk—in their missile-measuring race into outer space, Gates made a big show of staying above the fray: “Until we can get rid of malaria and tuberculosis, and all these diseases that are so terrible in poor countries, that’s going to be my total focus.… I do hope that people who are rich will find ways to give their wealth back to society with high impact. Clearly, they’ve got skills. They can’t, or shouldn’t, want to consume it all themselves.”CNN, which receives millions of dollars in charitable donations from the Gates Foundation, did not challenge Gates’s claimed moral authority or good-billionaire routine. If it were engaged in real journalism, it would, at the very least, have offered context.

It seems important to inform audiences, for example, about the very significant time and energy that Gates spends on self-enrichment and wealth accumulation. Through his climate-focused investment fund, Breakthrough Energy, Gates has invested money in a rocket company named Stoke. Elsewhere, he has a majority stake in the luxury hotel Four Seasons, and is reportedly the largest private owner of farmland in the United States. And, recently, Gates made a casual $500 million bet against Tesla, publicly acknowledging that it had only one purpose: to make money.

For a guy who publicly claims that his “total focus” is helping the global poor, Gates also appears to devote considerable time to sitting for self-aggrandizing interviews—often with news outlets that his private foundation funds. Talking to BBC, the recipient of millions of dollars from the Gates Foundation, he once again took softball questions about whether he had ambitions to go into space, using the opportunity to trumpet his philanthropic work on Earth. A child’s life can be saved for only $1,000, Gates noted, echoing similar claims he has made for years. It seems more than fair, at a point, to aim Gates’s data analysis at his own wealth. By Gates’s own figures, his $184 billion wealth could save 184 million lives—if he gave that money away.

This calculation, like much of Gates’s “numbers guy” routine, is pure pablum. But however you cut the numbers, Gates’s vast wealth could help the world in far-reaching ways, for example if it were redistributed as cash gifts to the poor. That can’t happen through the Gates Foundation’s father-knows-best, look-at-me brand of bureaucratic philanthropy. Gates isn’t interested in empowering the poor; he’s interested in imposing his solutions. Following the money from the Gates Foundation confirms this. Nearly 90 percent of the foundation’s charitable dollars go to organizations located in wealthy nations, not the poor countries he claims to serve. Never mind that the Gates Foundation’s website is inundated with the images of smiling poor people of color; in practice, the Gates model is funding white-collared bodies in the Global North to fix those wearing dashikis, burqas, saris, and kangas in the Global South.

A growing group of Gates’s intended beneficiaries today criticize him as doing more harm than good, and some have explicitly asked him to stop helping. “Bill Gates Should Stop Telling Africans What Kind of Agriculture Africans Need,” noted the headline of an op-ed in Scientific American, authored by Million Belay and Bridget Mugambe from the Alliance for Food Sovereignty in Africa. From farmer organizations in sub-Saharan Africa to public health experts around the globe to public school teachers in the United States, critics cite the high opportunity costs of Gates’s charitable crusades and the vast collateral damage they leave behind.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →No one elected or appointed Gates to lead the world—on any topic. Gates simply asserted his vast wealth to take power. He has put his hands on the levers of the world, trying to remake how we feed, medicate, and educate poor people according to his own narrow neoliberal ideology. The Microsoft founder even faces long-standing allegations of destructive monopoly power in his philanthropic ventures, as he has planted his flag and sought to take over fields like malaria research and health metrics.

There are few words that better describe this model of power—where the richest guy gets the loudest voice—than “oligarchy.” And no one has done more to normalize and institutionalize oligarchy than Gates. By masking his money-in-politics efforts under the banner of charity—instead of, say, lobbying or campaign contributions—Gates commands tax benefits, endless accolades, and public applause. Philanthropy has been very, very good to our “good billionaire.”

This lesson has not been lost on Jeff Bezos, Mark Zuckerberg, and hundreds of other billionaires who have pledged to follow in Gates’s footsteps, turning their vast private wealth into expansive political power through philanthropy, whether it is remaking climate policy, reshaping American public schools, or influencing the debate over how we regulate AI. That makes it all the more important that the rest of us also master this lesson. We have allowed Gates, Bezos, and Zuckerberg to become obscenely wealthy and now we are allowing these men to turn their wealth into tax-privileged political power through philanthropy. These are choices we can also un-make. But to do so, we must learn to see past the PR halo.

When the super-rich engage in charity, it has a way of not just scrambling our cognition, but also our humanity. The dollars on the table tempt us into a dangerous ends-justifies-the-means logic in which we focus on the enormous public goods that can be created through private wealth and ignore the known harms caused in its creation, or the antidemocratic power it engenders, or the alternatives at hand—most simply, redistributing billionaire wealth through taxation instead of philanthropy.

More on Bill Gates

The word “philanthropy,” from the Greek, means lover of humanity. A charitable gift is meant to be an act of love, not an exercise of power. Giving away money is not supposed to magnify the asymmetries in power that govern society but to collapse them. And this is why, in many respects, Gates might be better described as a misanthrope—if he does not hate his fellow human, then he certainly views himself as superior. Gates’s disregard for the wishes, needs, rights, dignity, intelligence, and talent of the poor people that he claims to be serving speaks to the fundamentally colonial lens through which he executes his charitable empire. It highlights the existential limits of what he can accomplish, and it explains why the Gates Foundation has achieved so little.

It’s not that Gates isn’t well intentioned, or that his charitable interventions have never helped anyone. Clearly, the tens of billions of dollars the Gates Foundation has given away have helped people at times and, yes, saved lives. But these wins should be viewed, at best, as a thin silver lining in a very dark cloud. At some point, we should understand that humanitarianism aimed at real human progress—equality, justice, freedom—requires us to challenge unaccountable power and illegitimate leaders, not worship them. And that means Bill Gates is a problem, not a solution.

More from The Nation

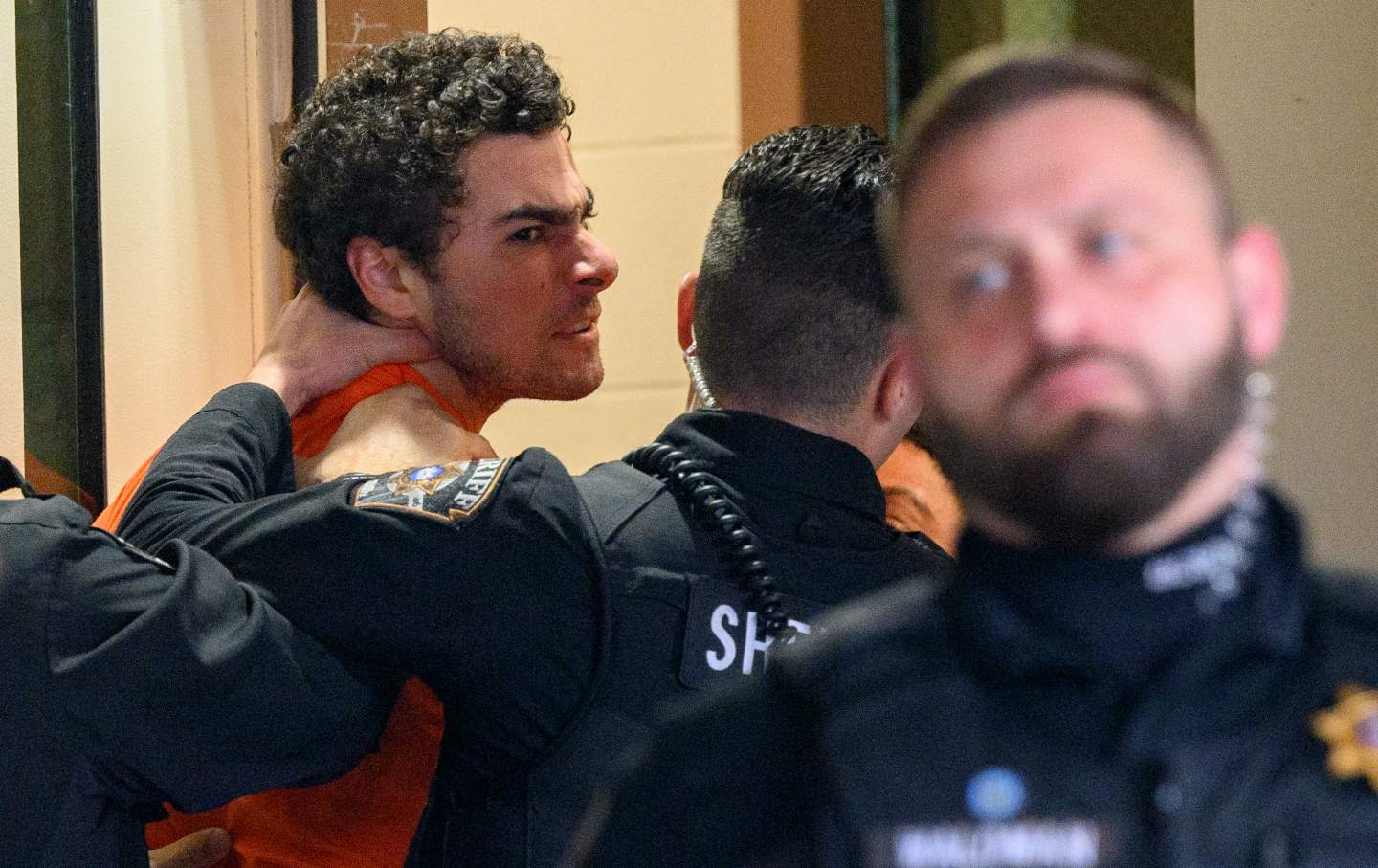

What Luigi Mangione and Daniel Penny Are Telling Us About America What Luigi Mangione and Daniel Penny Are Telling Us About America

When social structures corrode, as they are doing now, they trigger desperate deeds like Mangione’s, and rightist vigilantes like Penny.

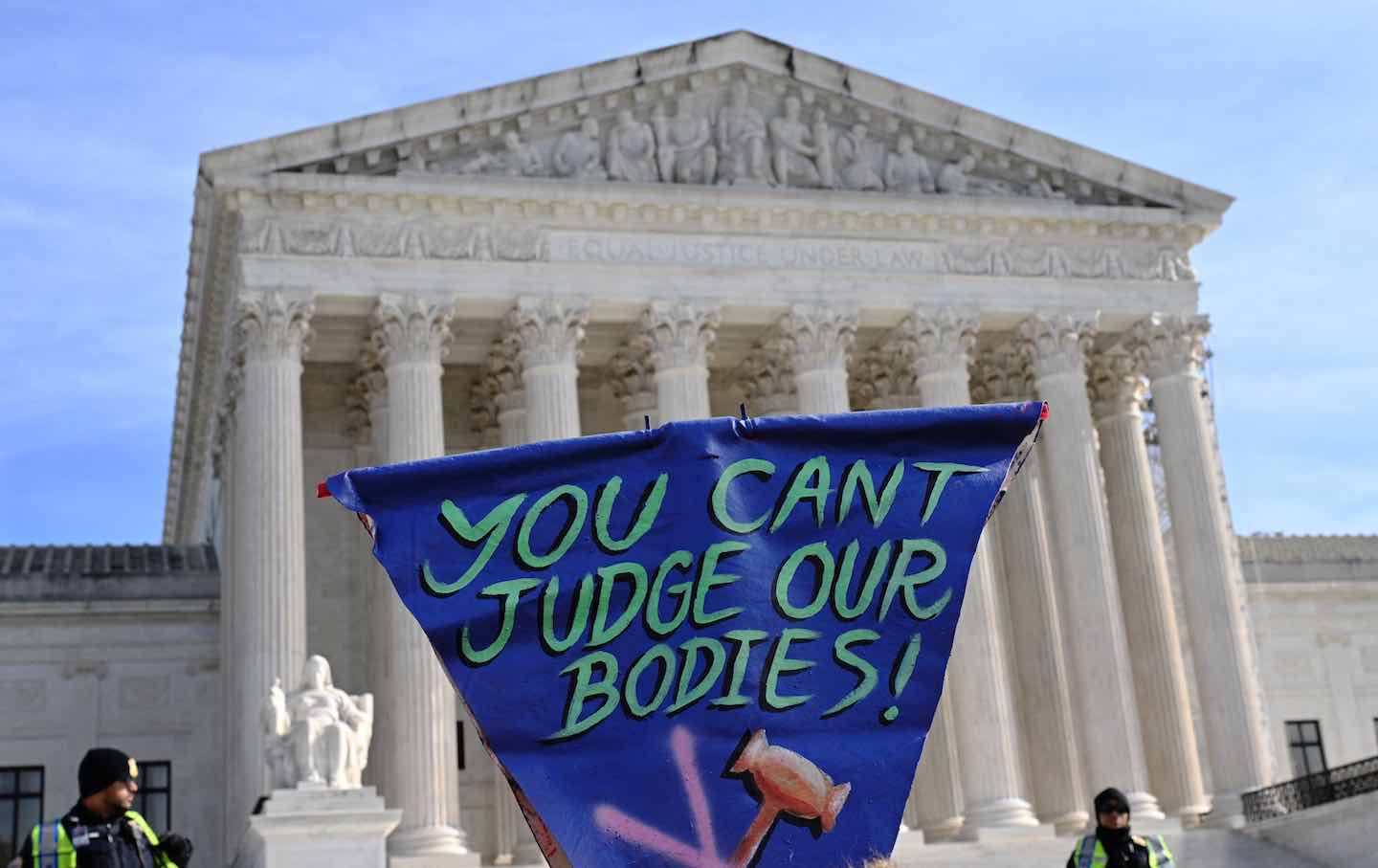

Banning Trans Health Care Puts Young People at Risk of Harm Banning Trans Health Care Puts Young People at Risk of Harm

Contrary to what conservative lawmakers argue, the Supreme Court will increase risks by upholding state bans on gender-affirming care.

It’s Still Not Too Late for Biden to Deliver Debt Relief It’s Still Not Too Late for Biden to Deliver Debt Relief

Four years after hearing the president promise bold action on student debt, most borrowers are still no better off, and many—especially defrauded debtors—are measurably worse off....

It’s Been a Tough Year. Let’s Help Each Other Out. It’s Been a Tough Year. Let’s Help Each Other Out.

There may be a dark shadow hanging over this year’s holiday season, but there are still ways to give to those in need.

Prison Journalism Is Having a Renaissance. Rahsaan Thomas Is One of Its Champions. Prison Journalism Is Having a Renaissance. Rahsaan Thomas Is One of Its Champions.

Thomas and his colleagues at Empowerment Avenue are subverting the established narrative that prisoners are only subjects or sources, never authors of their own experience.

Luigi Mangione Is America Whether We Like It or Not Luigi Mangione Is America Whether We Like It or Not

While very few Americans would sincerely advocate killing insurance executives, tens of millions have likely joked that they want to. There’s a clear reason why.