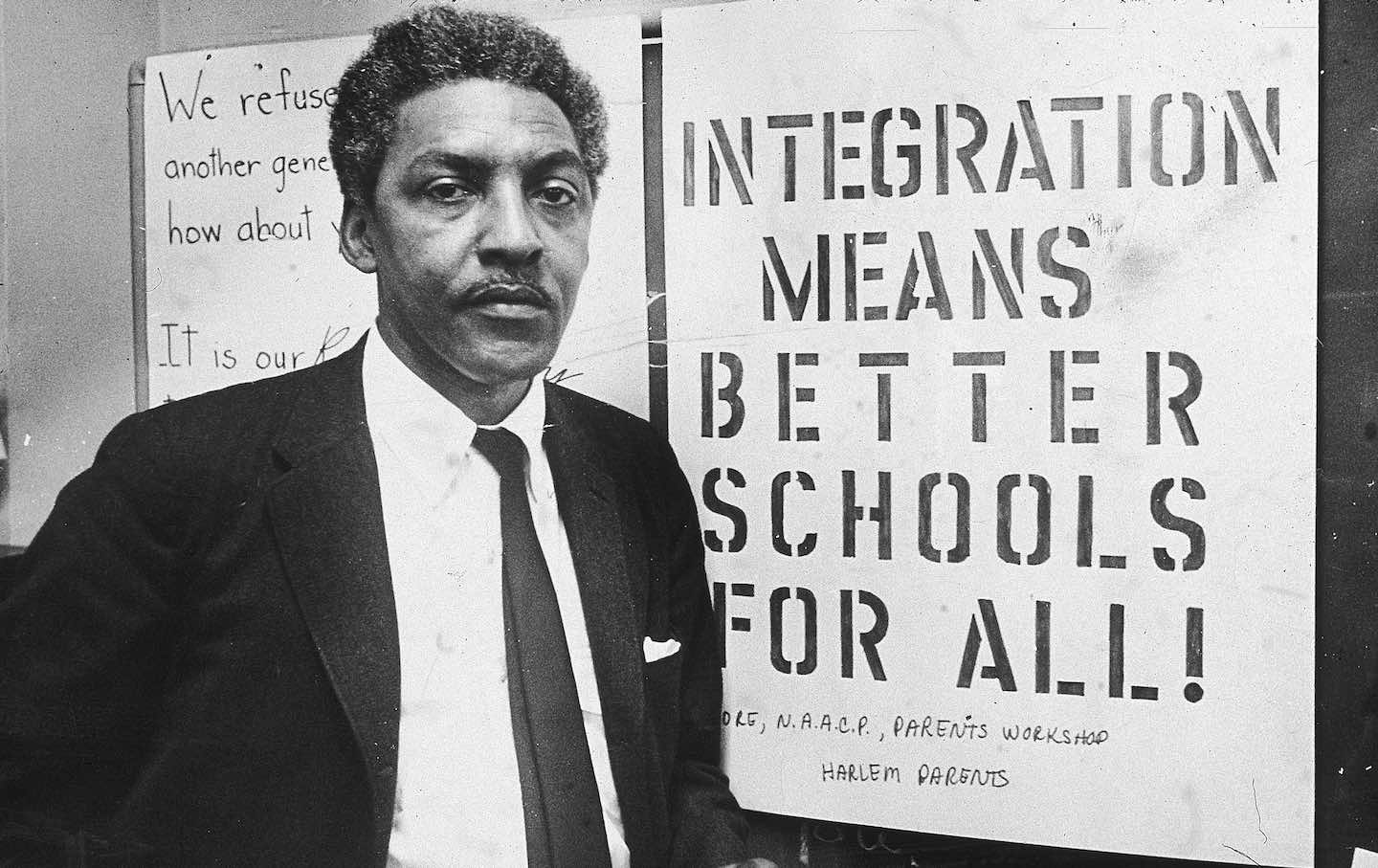

Bayard Rustin Was No Hollywood Figurehead

The new biopic about the socialist organizer stops at the March on Washington. What is it leaving out?

When I learned that Barack and Michelle Obama had announced a biopic on the socialist organizer Bayard Rustin through their production company Higher Ground, I shuddered a bit. Rustin was committed to a vision of egalitarian social transformation and sought to alter the terms of political debate toward that end; Barack Obama is not and never has been. After the movie’s release, the reports were no more promising. “It’s far worse than even you could imagine,” a friend told me, while another bemoaned its “malicious presentism.” Yet another friend, who was a politically active adult through the period the film covers, said, “The trailer was enough for me, and I couldn’t get through that.” But in the interest of service to my readers, I subjected myself to the whole thing. After it ended, I had to put on The Battle of Algiers as a purgative.

Rustin opens during the high period of activism in the Southern civil rights movement, with a montage of staged reconstructions of what the New York Times critic Manohla Dargis aptly describes as “stoic protesters surrounded by screaming racists.” This historical kitsch goes so far as to include a live-action version of Norman Rockwell’s painting of Ruby Bridges, surrounded by US marshals, walking to school in 1960. What follows, Dargis observes, “seeks to put its subject front and center in the history he helped to make and from which he has, at times, been elided, partly because, as an openly gay man, he challenged both convention and the law.” That’s the film in a nutshell. Rustin’s politics and his role in the crucial debates over ways forward from the legislative victories of 1964 and ’65 don’t come up in this story, which conveniently ends with the 1963 March on Washington.

In its effort to establish Rustin’s importance, the film falsely attributes to him the principal responsibility for proposing and executing the march, which actually originated with A. Philip Randolph and was largely organized by his Negro American Labor Council. It also downplays the role of the labor movement in organizing the march, treating the unions offhandedly as obstructionist and instead attributing their initiative to smart, energetic young people. Yet two months before the march, the United Auto Workers were central in organizing a 125,000-strong Detroit Walk to Freedom, essentially a trial run for the later event. Randolph and Rustin originally conceived the march’s focus as a demand for jobs and then broadened it to accommodate the Southern movement’s concern with Jim Crow. But the economic motive remained at the fore of the planning, Dargis notes, quoting Rustin himself: “The dynamic that has motivated Negroes to withstand with courage and dignity the intimidation and violence they have endured in their own struggle against racism may now be the catalyst which mobilizes all workers behind demands for a broad and fundamental program for economic justice.”

Ending the film at the march sidesteps Randolph and Rustin’s prime commitment to full employment and a social wage policy, which three years later they crafted and agitated for in the Freedom Budget for All Americans. Some of Rustin’s most significant political interventions occurred after the march, in particular his Commentary essays of 1965 (“From Protest to Politics: The Future of the Civil Rights Movement”) and 1966 (“‘Black Power’ and Coalition Politics”). The first argued that, with the legislative victories of the mid-’60s, the Black movement had crossed a threshold that called for collaboration with labor and liberals to advance a broadly social-democratic agenda. In the second, contrasting the Black Power sensibility to the Freedom Budget, Rustin noted that “advocates of ‘black power’ have no such programs in mind; what they are in fact arguing for (perhaps unconsciously) is the creation of a new black establishment.” It might hit too close to home for the Obama vehicle to reflect on that assessment nearly 60 years down the road.

Those elisions reflect the film’s “malicious presentism” in its desire to create an exalted Rustin more amenable to contemporary neoliberal sensibilities. This line of criticism is certainly the tack readers would expect me to take. There never was any reason to believe that a production with the Obamas’ nihil obstat would come within a zip code of Rustin’s own working-class-based, social-democratic politics. But the movie’s problems run deeper, baked into its Oscar-bait formula. Standard-issue Hollywood biopics perpetually fail to capture how movements are reproduced as mass projects, from the bottom up and top down, in a constantly improvised trajectory plotted in response to and in anticipation of layers of internal and external pressures. But that’s not their point. Rustin isn’t interested in illuminating the intricacies of the civil rights movement; it wants us to recognize his place in a pantheon of Black American Greats. Toward that end, it keeps telling us—over and over—how close Rustin was personally to Martin Luther King Jr., as though propinquity to Universally Recognized Greatness cements his place in the pantheon.

Rustin was a brilliant organizer and strategist, not least because he was motivated by a practical utopian vision of the society he wanted to realize. That vision, and his recognition of the path toward it, helped him to parse in a distinctively clear way the tensions and contradictions within the movement, particularly as it faced major crossroads in the mid-1960s. Rustin was probably not, as the movie has Randolph say to Roy Wilkins when discussing the march, the “one person who can organize an event of this scale.” He was instrumental in organizing it, though, as well as in other important initiatives in the period. He was also the consummate staff person, who understood his role as executing collectively defined objectives. That’s typically not the kind of role that leads to an assignment in the pantheon of larger-than-life greats. Unfortunately, in the hegemony of a culture that looks for The One—from John Galt to Neo to Martin Luther King Jr. to DeRay McKesson—an appreciation of Bayard Rustin requires attempting to shoehorn him into the Justice League, not grappling with him as an agent within the history he lived.