This Journalist Is Uncovering the Dirty Side of Fast Fashion

Alden Wicker, author of To Dye For, wants our clothes to stop poisoning us.

Alden Wicker

Brooklyn, N.Y.—Journalist Alden Wicker examines a neon orange purse that’s selling for $14.99. She pulls a tag out of the bag: Instead of listing materials, it just says “vegan.” She raises an eyebrow. “Excuse me,” she asks a store clerk. “Can you look up the materials for this bag?”

Wicker and I have just stepped into an H&M pop-up in Williamsburg. The store clerk she’s waved over looks up the materials on his phone: The coating is polyurethane, and the lining is polyester. In other words: plastic.

For the last decade, Wicker has been covering the dirty side of fast fashion—from its contributions to the climate crisis to greenwashing to multilevel marketing schemes like the leggings brand LulaRoe. In 2013, she founded the blog EcoCult, and she soon became perhaps the most popular authority on sustainable fashion.

Her book, To Dye For, asks readers to consider the impact that chemically treated fabrics and synthetic fibers can have on your health. Wicker spent two years interviewing flight attendants, garment workers, physicians, researchers, industry experts, US consumers, and workers in the places where we source our clothes. She describes a supply chain rife with toxic chemicals—like formaldehyde and chromium, which are both carcinogenic—and endocrine-disrupting polyfluoroalkyl substances (also known as PFAS), which are linked to infertility and other health issues. And despite the potential harm, she discovered that the government has done little to protect consumers from the clothes they wear.

“We’re allowing chemicals to be poured indiscriminately into the environment, but we’re also bringing them into our homes,” Wicker tells me. The effects of these chemicals on textile workers and their communities were well-documented, but Wicker worries that the issue remained abstract to US consumers. “This isn’t an ‘over-there’ problem.”

Wicker got the idea for the book in 2019, when a radio producer called to ask if she could comment on a lawsuit filed by Delta employees against Land’s End alleging that the company’s uniforms were making them sick. “I’d heard nothing about fashion or textiles being toxic enough to affect people’s health,” she tells me. In fact, flight attendants at several major airlines were complaining of rashes, hair loss, fatigue, brain fog, heart palpitations, and breathing problems. “Their bodies would start shutting down,” she says. “They couldn’t work, and in some cases that completely ruined their lives.”

Early in the book we meet John, an Alaska Airlines flight attendant who developed a litany of health problems, including trouble breathing and blistering on his arms, right after he received a new uniform. Researchers at Harvard University attributed the attendants’ reactions to the long time they spent in them—flight attendants sometimes wear their uniforms for up to 24 hours at a time. A combination of chemicals, like anti-wrinkle and anti-stain resins and disperse dyes, can leach into the skin through sweat.

The flight attendants are just an extreme case of clothes making people sick, Wicker tells me. Over the course of her reporting, she dug up lawsuits against the children’s-clothing brand Carter’s and Victoria’s Secret, where people said their clothes gave them severe rashes. It’s difficult to prove the toxicity of a piece of clothing, she says, because a single shirt may have passed through several factories and can contain an untold number of chemicals.

“There’s no ingredient list in fashion,” Wicker says. “If you’re allergic to nickel or disperse dyes or formaldehyde, you can avoid it in beauty products, cleaning products, food products—but not in fashion.” In the book, she speaks with researchers who connect declining fertility rates and the rise of autoimmune diagnoses in the United States with chemicals found in our clothes.

We stop for coffee on Sixth Street, where Wicker tells me about the people she interviewed for To Dye For. She spent time with a textile worker in Tirupur, in southern India, whose arms and legs were covered in blisters that only started to disappear after she quit her job. She interviewed a California marketing executive whose dye allergies had caused her to scratch herself until she bled in her sleep. After eventually identifying the chemicals she was allergic to, she got rid of the clothes that were causing her reaction.

She never met John, the flight attendant, because he died in 2021, at age 66, of a heart attack. Wicker spoke with his widower, who is certain the Alaska Airlines uniforms caused the health problems that led to John’s death. “You can draw a straight line from Leelavathi in India to this woman in California and their skin issues,” Wicker says. “The woman in California has more resources than the garment worker, and they live very different lives, but living in America doesn’t shield you from this.”

The European Union, and even the state of California, have cracked down on toxins in fashion—Wicker would like to see the federal government do the same. In the book, she calls for more research into the chemicals that go into making our clothes and for empowering regulators to test and recall toxic items. And, she says, there are many more protections the federal government could institute, like requiring ingredient lists on fashion products and cracking down on greenwashing. “Wouldn’t it be great if we switched to a precautionary principle where, when it comes to chemicals, it’s not innocent until proven guilty?” she asks. “Let’s make sure they’re safe before we use them.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →On the street, we had passed by storefronts prominently displaying their dedication to sustainability. A bedding and home goods retailer touts a “climate neutral” certification in its window. The clothing store Madewell is selling “preloved finds” for a limited time. A cosmetics shop exhorts passersby to “help us end beauty packaging waste.”

Wicker is wearing white cotton tank top with rigid white jeans and a striped wool cardigan. She avoids bright dyes and stretchy fabrics, partly out of the concerns she outlines in her book but also because it’s not her style, she said. She warns against so-called “performance materials” that repel water and stains and tout wrinkle resistance—those tend to contain PFAS.

She’s wary of what she calls conscious consumerism—even if this book is an appeal for consumer safety. “I don’t want this to become a ‘shop your way out of it’ thing,” she said. She seized on a piece of advice from one of her interviewees, a researcher at Duke University who found high concentrations of potentially carcinogenic Azo dyes in children’s clothing. “I asked how she changed her shopping habits. She said: ‘Just shop less.’”

More from The Nation

Notes on Transsexual Surgery Notes on Transsexual Surgery

An abundance of plastic surgery is not a net good. But discussions over its morality would be better off viewing it less as unfettered desire and more as self-determination.

I Led the FDNY. Don’t Believe Elon Musk’s Nonsense About It. I Led the FDNY. Don’t Believe Elon Musk’s Nonsense About It.

Musk’s attack on the new FDNY commissioner proves he knows nothing about how modern fire departments work.

What Black Youth Need to Feel Safe What Black Youth Need to Feel Safe

Young people are facing a mental health crisis. This group of Cincinnati teens thinks they know how to solve it.

Trump’s Death Eaters Are Coming for Our Kids Trump’s Death Eaters Are Coming for Our Kids

After taking countless lives around the world, RFK Jr. and his ghoulish compatriots want American children to suffer too.

The Supreme Court Just Held an Anti-Trans Hatefest The Supreme Court Just Held an Anti-Trans Hatefest

The court’s hearing on state bans on trans athletes in women’s sports was not a serious legal exercise. It was bigotry masquerading as law.

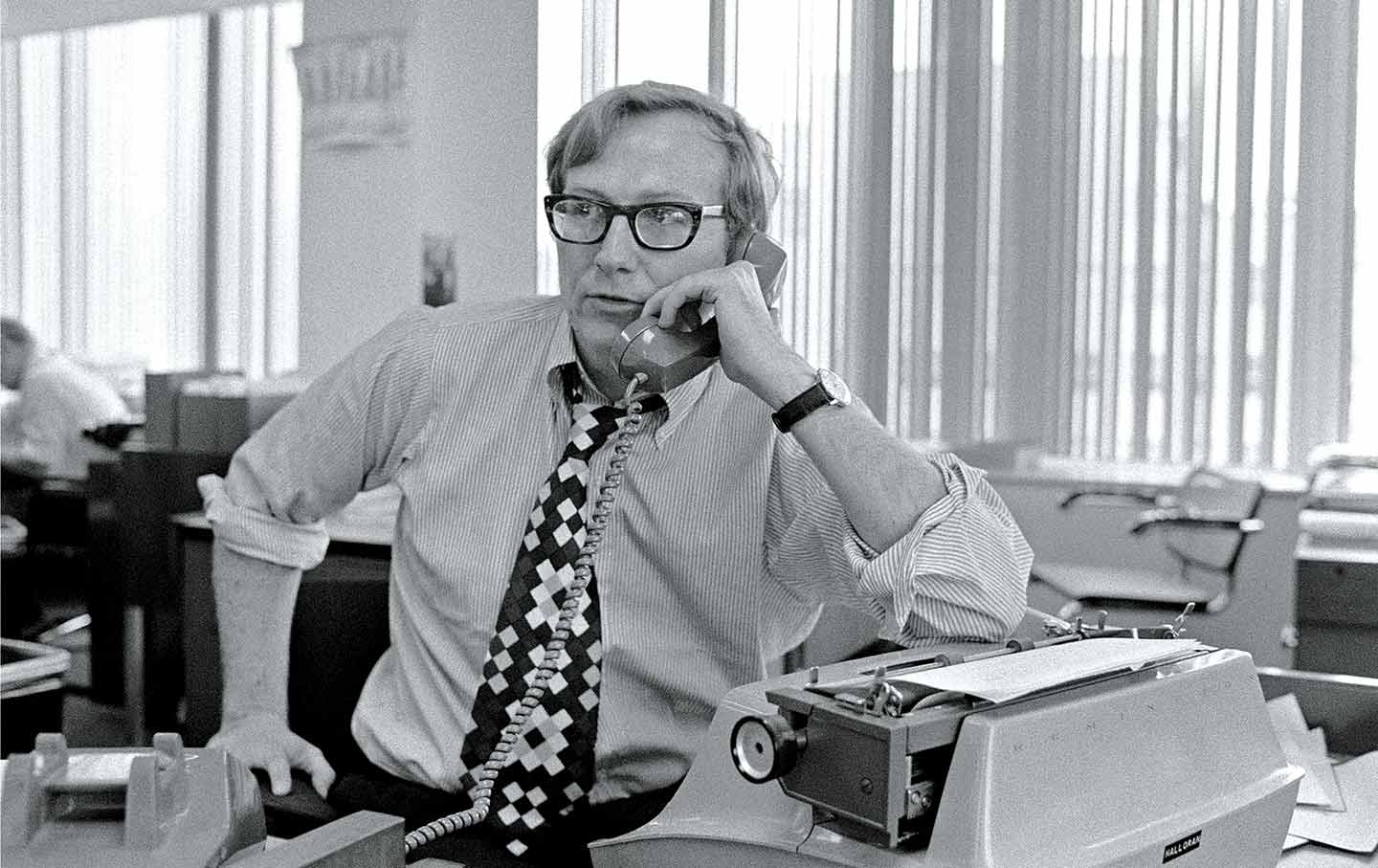

The Endless Scoops of Seymour Hersh The Endless Scoops of Seymour Hersh

Laura Poitras and Mark Obenhaus’s Cover-Up explores the life and times of one of America’s greatest investigative reporters.