Democrats had a moment of panic in February, when a Quinnipiac University poll showed Donald Trump beating the party’s various presidential contenders by wide margins—seven to 11 points—in Wisconsin.

The panic was understandable. Political seers have identified Wisconsin as a must-win, with The Washington Post explaining, “Many pundits and pollsters have declared that the state could be the tippiest of tipping points” in the fight for an Electoral College majority in 2020.

If Wisconsin had, indeed, tipped to Trump, it wasn’t simply an embarrassment for the swing state’s Democratic cadres, who are still trying to explain how historically Democratic loyalties were abandoned in the last presidential election. It was a nightmare for national Democratic officials as well, because, as New York Times election guru Nate Cohn observed in his 2020 Electoral College breakdowns, “One reason that [even] such a small swing in Wisconsin could be so important is that the Democrats do not have an obviously promising alternative if Wisconsin drifts to the right.”

So if the Quinnipiac poll was right, all hope was lost. Social media clogged up with predictions of impending doom. Then Representative Mark Pocan, a Wisconsin Democrat and cochair of the Congressional Progressive Caucus, pulled out his cell phone and advised calm. “Outlier poll, folks. Breath[e],” tweeted Pocan, who has won 15 elections at the local, state, and federal level over the past 30 years. “Doesn’t look like [the] others at all.”

He turned out to be right. Wisconsin hasn’t been lost. Ensuing polls put the state right where it has been for most of the past four years: too close to call. As of mid-March, the RealClearPolitics survey of recent polls had Trump tied with Joe Biden at 45 percent and a point behind Bernie Sanders, 45.2 to 46.2 percent. Trump won’t run away with Wisconsin. The question is whether any Democrat will turn out enough new voters and win back enough swing voters to beat him. That question is now complicated by the coronavirus outbreak and the vast economic upheaval associated with it. But basic premises still apply.

“If this is a close election, whoever wins Wisconsin will be the next president,” says Democratic Party of Wisconsin chair Ben Wikler. A top national organizer for MoveOn who returned to his home state and was elected to lead the party there, Wikler has spent the past year explaining the calculus that has Wisconsin and national Democrats obsessing. “All the states where Trump is more popular than he is in Wisconsin don’t add up to enough Electoral College votes to win the presidency. Neither do all the states where Trump is less popular than he is in Wisconsin. So if the Electoral College vote is close, Wisconsin is the most likely state to tip the balance.”

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

This isn’t just a party chair talking big about the turf he works. The Democratic National Committee is so serious about Wisconsin that it decided to hold the party’s highest-profile event of 2020 there: the national convention that Democrats still hope will happen in Milwaukee this summer.

But it will take more than a convention to swing Wisconsin. For Democrats to win in November, they have to get everything right—as they did in the 2018 midterm elections, when the party won every statewide race on the ballot, throwing out right-wing Republican Governor Scott Walker and his attorney general and reelecting liberal Democratic Senator Tammy Baldwin.

The Democrats have to build a multiracial, multiethnic campaign that excites and mobilizes voters in Milwaukee and other cities with substantial nonwhite voting blocs, such as Racine and Beloit; renew the party’s appeal in rural counties, where its support collapsed four years ago; overcome voter suppression strategies put in place by the Republicans; and develop a platform that speaks to the issues that concern Wisconsinites—especially women, whose support for Democratic challenger Tony Evers, at 54 to 45 percent, ousted Walker two years ago. And the party has to field candidates for president and vice president who know the state, recognize its importance, and pay it the time and attention required to pull those threads together.

“Pretty much, you have to do it all,” says Peter Rickman, a Milwaukee union organizer and activist who has been intimately involved in every major progressive Wisconsin campaign over the past decade. “And if you lose a piece, if it doesn’t come together, sure, we could lose.”

Plenty of pundits have their one-size-fits-all theories for what ails the Democratic Party, both nationally and in places like Wisconsin. Some of those theories, especially the ones advanced by never-Trump conservatives in the studios of MSNBC and the op-ed pages of The New York Times, are so off base that one of Wisconsin’s new generation of elected officials, state Treasurer Sarah Godlewski, says, “Sometimes I just shake my head. I mean, have they ever even been to Eau Claire?”

Don’t get Godlewski wrong. She’s worked for the State Department and traveled the world, and she was a national finance council cochair for the Ready for Hillary super PAC. But like all of the Wisconsinites I asked about what it will take to win in 2020, Godlewski warned against imagining that a simplistic focus on gut instincts or even sophisticated data-driven schemes will be enough to close the deal in a state with a political history so complicated that it has, over the past century, put fiery left-wing populist Robert M. La Follette and fearmongering red-baiter Joe McCarthy on the national stage. There is no easy way around the fact that Wisconsin—a state that backed every Democratic presidential nominee from Michael Dukakis in 1988 to Barack Obama in 2012—joined two other historically Democratic states (Michigan and Pennsylvania) to reject Hillary Clinton in 2016 and tip the Electoral College to Trump.

Every serious search for a winning formula in Wisconsin begins with a forensic examination of what went wrong in 2016. People have plenty of answers, all of them grounded in the bitter reality of a Democratic campaign that missed its mark. Clinton did not make even a single appearance in Wisconsin throughout the fall—an absence that made it harder for her to address concerns about her past support for free-trade deals in a state where cities like Milwaukee and Janesville have been battered by deindustrialization. At the same time, her campaign failed to recognize that Trump was selling a narrative that would win over some traditionally Democratic voters and cause many others to stay home.

Generic Democratic campaign ads focusing on Trump’s crude sexism may have shored up support among the state’s confirmed Clinton voters, but they failed to move the conservative suburban women she was seeking to attract. One of her key 2016 backers says, “We would call Brooklyn [where the national campaign was headquartered] and say, ‘This doesn’t feel right. This isn’t working.’ And they would say, ‘Relax, we’ve got data that says we’re going to win big.’”

Instead, Clinton lost small, falling short by just 0.77 percent of the vote. Compared with Obama’s substantial victories in the state—he garnered 56 percent of the vote in 2008 and 53 percent in 2012—her 46.5 percent finish seems dismal. But the fact is that his robust margins were outliers; Democrats have often had to claw their way to victory in Wisconsin. Bill Clinton won there in 1992 and 1996, but he never got 50 percent of the vote. Al Gore’s advantage over George W. Bush in 2000 was a mere 5,708 votes. John Kerry won against Bush in 2004 by 11,384 votes. “We’ve long been balanced on a knife’s edge,” Wikler observes. “Trump’s under–1 percent margin of victory in 2016 was a return to form.”

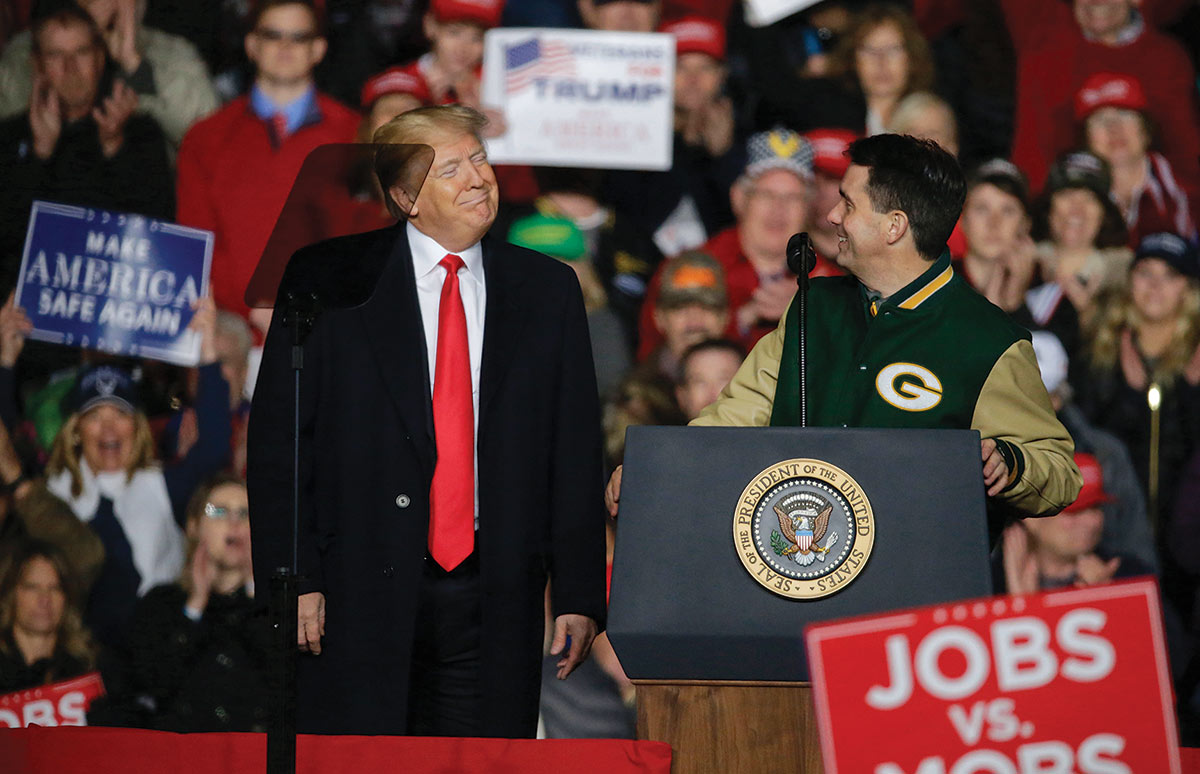

That may be somewhat comforting to Democrats who thought everything went to hell the last time around. But it shouldn’t be, because the party that was always able to eke out a win couldn’t beat Trump in 2016. Since taking office, he and Vice President Mike Pence have made the state a regular stop, with Trump postponing a planned March rally only after an outcry about a mass event being scheduled as the coronavirus outbreak spread.

“Donald Trump has a movement behind him. Just because it’s rooted in xenophobia and white supremacy doesn’t make it any less of a mass movement,” says Jennifer Epps-Addison, a longtime Milwaukee organizer who now serves as the president and a co–executive director of the Center for Popular Democracy. “We have to have a candidate and a campaign with a movement behind it to beat Donald Trump.”

The president, who admitted that he was surprised to win Wisconsin, is full of confidence now. His campaign mirrors that bravado. “No matter which socialist emerges from this bruising primary,” Trump’s Wisconsin campaign spokesperson, Anna Kelly, said in a statement, “they stand no chance against our top-notch permanent ground game, unparalleled data program, and vast fundraising war chest that will once again propel President Trump to victory in November.”

Walker’s backers peddled that sort of spin before his defeat in 2018, and Democrats certainly stand a chance in 2020. But, Pocan says, they have to run an “all of the above” campaign, one with “a Milwaukee strategy, a rural strategy, a midsize-city strategy. It’s got to be all about turning out the vote in all the places where Democrats can get votes. And that’s just the start. It has to be about how the message is framed and who frames it.”

Pocan, a Sanders backer, argued that the Vermont senator could renew the state’s Democratic coalition—especially in places like Pocan’s hometown of Kenosha, historically a manufacturing center that has seen major factories close in a county that gave Trump a 255-vote win (out of more than 75,000 cast) in 2016.

The concern that many Wisconsin Democrats expressed regarding Biden has to do with the issue of trade policy. It’s a problem he has to address aggressively.

“Our best shot at winning Wisconsin was always to nominate a progressive who understands not just how disastrous Trump’s trade wars have been but also why the neoliberal trade policies of the Clinton administration are still haunting the politics of the Midwest,” Epps-Addison says. “Democrats have to understand that nominating supporters of NAFTA really can depress votes and make it significantly harder to win in November.” Because Trump certainly understands this. If Biden is his opponent, Trump will weaponize every pro-free-trade statement Biden ever made.

Biden can mitigate his vulnerability by detailing Trump’s broken promises on trade policy and pointing out the ways the president has used Wisconsin workers and farmers as pawns in his wrangling with China and Mexico. The presumptive Democratic nominee can also pick a running mate with a better record than his. Wisconsinites love the idea of his choosing Baldwin, a progressive who has sided with Sanders on many key issues. But the deeper point they make is that his vice presidential pick should be a woman as well as someone who gets economic populism. No matter who’s on the ticket, however, Wisconsin activists, strategists, and officials say there are some basic focuses necessary to win the state and the presidency.

§ Economic populism: Wisconsin’s identity remains wrapped up in its factories and farms and the political traditions that extend from them. It’s a place where progressive populist messages work—Sanders won 71 of 72 counties in his 2016 primary fight with Clinton—and where even Republicans frame their policy agendas, however cynically, as attacks on elite privilege. Now, however, with the coronavirus outbreak upending every economic calculation, the Democrats’ populism must be focused and forward-looking. “It’s not enough to say, ‘Bad trade deals have hurt workers and farmers.’ It’s got to get beyond slogans,” argues Rickman, who maintains that the Democratic nominee must acknowledge not just Republicans but also many Democrats who were too deferential to Wall Street.

Yet while frankness is critical, realism is, too. “You can’t just hearken back to the past and say, ‘We’re bringing all the manufacturing jobs back,’” he adds. “That’s what Trump does, and people understand now that he’s lying. Candidates have to recognize that people don’t necessarily miss manufacturing jobs. They miss the good pay and the good benefits that went with manufacturing jobs. The Democratic nominee has to talk about how a Democratic administration would transform the jobs of today and tomorrow—service jobs, warehouse jobs, call-center jobs—into the high-paying jobs of the future. And it can’t just be feel-good talk. It has to focus on balancing the power in the economy between the boss class and the working class.”

§ Organize the hell out of Milwaukee: While the voter suppression schemes implemented by Walker and his allies have done damage, Wisconsin remains a high-turnout state with close elections. The balance is often tipped in the Milwaukee area, with a multiracial, multiethnic city that is heavily Democratic and overwhelmingly white suburbs that are heavily Republican.

Dating back to Walker’s 2010 election and the fight over his anti-labor agenda, which sparked an unsuccessful recall election in 2012, Wisconsin Republicans and national groups like Americans for Prosperity have poured resources into organizing the so-called WOW counties (Waukesha, Ozaukee, and Washington) that surround Milwaukee. Meanwhile, the Democrats and their allies, including the unions weakened by Walker’s assaults on the right to organize, have focused on the city—and for good reason. When Milwaukee turnout is off, as it was in 2016, Democrats have a hard time making up the difference even when they get huge margins in the vote-rich and very progressive state capital of Madison and surrounding Dane County.

Epps-Addison, who’s been organizing for decades, points out that groups already on the ground—BLOC (Black Leaders Organizing for Communities), LIT (Leaders Igniting Transformation), the African-American Roundtable, and Voces de la Frontera among them—“have done a lot of the work already. So invest in those grassroots organizations early to allow them to launch their field programs now. Don’t wait until after the convention. Don’t wait until the fall.”

The Democratic Party’s Wikler and other Wisconsin activists recognize that the coronavirus outbreak could seriously complicate traditional organizing strategies. As a result, they’ve developed sophisticated plans to go virtual. “The key is to keep connecting with people in the most direct ways we can,” he says. “We can’t stop organizing, because we know how close the election could still be.” The 2018 midterms were close as well, and it looked as if Republicans would win most of the statewide contests. Then the Milwaukee results came in, and Democrats took the races for governor and attorney general by under 30,000 votes. Something like that could happen again in 2020.

§ Organize the hell out of Eau Claire: Wisconsin’s smaller cities, like Eau Claire and La Crosse in the west, Janesville and Beloit in the south, Racine and Kenosha in the southeast, and Oshkosh, Appleton, and Green Bay in the northeast, all send Democrats to the state legislature. Most are historically industrial centers; several have established African American communities and growing Latino populations. Many of the organizing strategies that apply in Milwaukee will apply in smaller cities as well. And these places are 2020 battlegrounds. Trump’s campaign rallies, in 2016 and since, have targeted many of these cities. But they are also places where his promises have not been kept.

Last fall, Wikler notes, the Democrats launched “a wave of organizing unprecedented in scope this far from an election.” He says this ambitious organizing at the neighborhood level in Milwaukee and other communities statewide—framing agendas at the grass roots and empowering “messengers with local credibility” to deliver them—will give the Democratic nominee a head start. If organizing can go door to door in the fall, it will. If it has to be virtual, so be it. No matter the challenges, once the ticket is chosen, he promises, it will be time to “hit the turbo button.” If the candidates complement this strategy by focusing on Wisconsin in their messaging and, where possible, in their campaigning, the pieces, he says, will come together.

§ Reconnect with rural Wisconsin: As veteran Democratic activist Charlie Uphoff points out, “Trump didn’t win Wisconsin because of who showed up in 2016. He won because of who didn’t show up.” A huge portion of the Democratic drop-off came in rural Wisconsin.

Consider Walworth County, a Republican-leaning bastion of small towns and farms where Trump won 56.1 percent of the ballots and a 10,153-vote majority in 2016—almost half of the Republicans’ statewide margin of 22,748 votes. But the Democrats didn’t always perform so miserably in the county. In 2008, Obama received 48 percent of the vote there. In 2012 he still attracted 43 percent. What happened in 2016?

In the last presidential election, the overall turnout in Walworth County was down a bit from 2012, but the decline was not evenly shared: Trump received 143 fewer votes than Mitt Romney did in 2012, while Clinton got 3,802 fewer votes than Obama. The Democrats don’t have to carry every rural county. They don’t even have to flip Trump voters. They just have to get their traditional voters to the polls and attract some new ones, especially young people.

They can do that by highlighting Trump’s whipsawing of farmers as part of his trade negotiations and more generally by discussing farm issues, says Jim Goodman, who farmed for 40 years in western Wisconsin and is now president of the National Family Farm Coalition. He argues that Biden must talk a lot more about farm issues in his campaign and the party has to write a platform that devotes more than just a few dozen words to rural and small-town concerns, as was the case in 2016.

This is about paying attention to the reality that underemployed and underinsured rural voters have pressing needs that too frequently go unaddressed. “The right wing spends a lot of time trying to sow disunity between communities that don’t see much of each other,” Epps-Addison says. “The way to counter that is to have a campaign that seeks to unite folks on what we have in common—the fact that more and more folks are struggling in this economy, the fact that more and more folks are worried about how they can afford health care. We know the issues. We just have to think about how to speak to them in ways that connect with people where they live.”

That is going to require candidates who get it and a program that speaks in compelling terms to Wisconsin. It is also going to require the resources to deliver that message at the doors of the disengaged, disenfranchised, and disappointed people whose votes can expand the electorate and create a winning coalition. Where will the money come from? Pocan has what is perhaps the best suggestion. “Don’t just throw money up on TV so that consultants get rich,” he says. “It can’t be about ads. This isn’t a 30-second discussion. This is about reconnecting with people who may not have voted last time and connecting with people who may be voting for the first time. That’s how you win Wisconsin.”