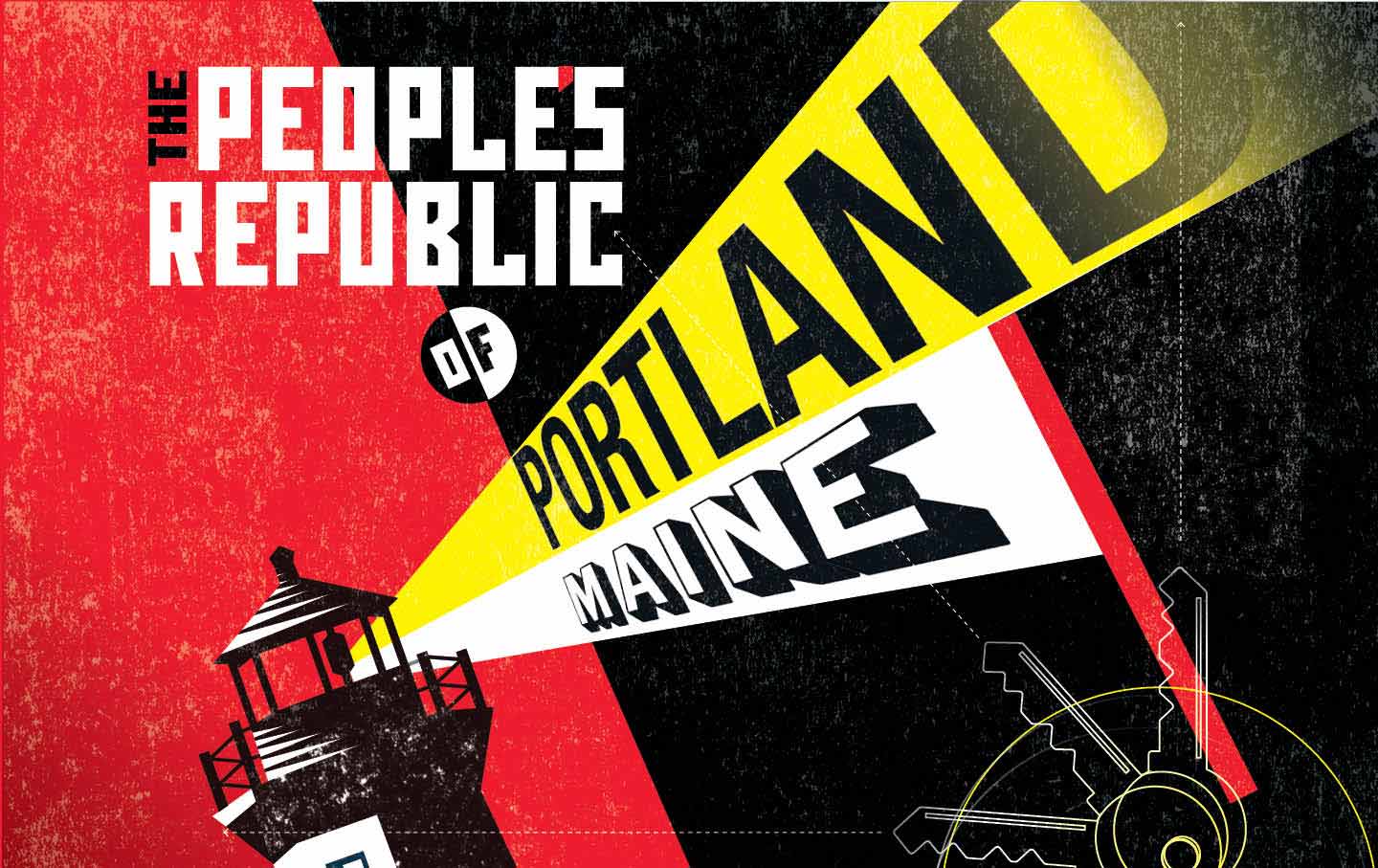

The People’s Republic of Portland, Maine

Local organizers have gotten the New England town to pass some of the most progressive legislation in the country. Will it stick?

“I’m very pro-union,” says Sam Colson, a 53-year-old bus driver and member of the Amalgamated Transit Union. Colson lives in a one-bedroom apartment in Portland, Me., with his 26-year-old son. They share the $1,570 rent, and Colson pays the $135 fee for their parking spot. For them, making the rent each month is manageable. But for many people they know, like those working in the city’s myriad restaurants and breweries, downtown rental prices have become simply unaffordable. So Colson got to work establishing the Wadsworth Tenants Union earlier this year, after his landlords repeatedly failed to address residents’ concerns about safety and rent increases.

Colson is a big man, with a clean-shaved head, silver hoop earrings in each ear, and a gray goatee. “It gives you a lot of time to think, driving a bus,” he says over breakfast in the rail car that holds the Miss Portland Diner. “You’re in your head a lot.” Colson’s long-term plan is to link the tenants in every big building in the city together in a Greater Portland Tenants’ Union Association. “There’s strength in numbers,” he says.

Over the past three years, faced with a spiraling crisis of affordability and supply in the rental market, housing activists in Portland have proved Colson right, racking up one electoral victory after another. Grassroots organizers in the tenants’ rights community, including many members of the Democratic Socialists of America, have pulled off what must surely rank among the most remarkable electoral victories at the local level for the progressive left nationwide.

They have won rent control for all buildings except owner-occupied ones with four or fewer units, limiting rent increases to 70 percent of the rate of inflation. (Many of the fixed expenses that landlords face, based on mortgages secured when interest rates were very low, don’t go up at anywhere near the rate of inflation, proponents argue.) They’ve secured the passage of an inclusionary zoning ordinance that increases the proportion of units that have to be set aside as affordable housing. They’ve persuaded voters to back a Green New Deal that introduced better labor and environmental standards for the construction of new properties. They’ve set up rent boards to hear tenant complaints and extended the notice period for landlords seeking to evict to 90 days. (Maine’s law allows for no-cause evictions, so Portland couldn’t simply outlaw the practice.) They have also presided over the creation of a number of tenants’ unions to fight predatory landlords.

Arguably, no other midsize American city has come close to Portland in terms of the sheer audacity of the housing initiatives that voters have approved, or in reimagining the landlord-tenant relationship. And yet, like so many other cities and towns in America, Portland remains in the grip of a housing crisis.

This is a story of the power of grassroots organizers to effect large-scale policy changes in the face of official intransigence. But it is also a cautionary tale about the barriers these efforts face—from noncompliant landlords to developers pulling back from projects—and the opposition that kicks into gear when it comes to genuinely overhauling conditions on the ground.

The struggle over tenants’ rights and affordable housing in Portland had been a long time coming. For people of good faith on both sides of the rent control and inclusionary housing debate, the crisis demanded a serious response. “There is a huge shortage of affordable and low-income housing,” says 26-year-old Izzy Ostrowski, who once worked for an organization that did outreach with the homeless and is now working as a nanny and paying $1,093 a month for a small studio apartment. “So a majority of people can’t afford to live their lives and also not experience housing insecurity. We’re seeing huge numbers of folks experiencing homelessness for the first time, families experiencing homelessness. Portland prioritizes wealthy tenants and tourists who are uncomfortable seeing poverty. There’s a disproportionate impact in communities of color being displaced. I know a lot of people who’ve moved out of Portland.”

Jonathan Culley, the president of Redfern Properties, one of the largest apartment developers in the city, acknowledges the severity of the problem. Culley sits on the board of Avesta, the largest nonprofit provider of affordable housing in northern New England. “I see safe, healthy, affordable housing as a human right,” he says. “Our society doesn’t do nearly enough to make sure everyone is safely housed.” Yet he worries that if the local market is overburdened with regulations, the number of affordable housing units under development might actually fall as developers pull up stakes and move out of town. Far better, he says, to lobby politicians in D.C. to pass laws subsidizing the rapid construction of affordable housing units nationwide; far better to get state and federal agencies to build social housing directly. Far better too, he adds, to trim the military budget and funnel a few tens of billions of dollars into expanding the nation’s stock of non-market-priced housing. Absent such federal intervention, Culley fears, local efforts to tackle the crisis might make a bad situation worse.

That view, it appears, was also the one taken by the Portland City Council in the years leading up to 2020. The council remained largely paralyzed on the issue, even as federal inaction made creative local responses to the growing housing crisis an urgent matter. Rents were skyrocketing in Portland, a city of 70,000 people (more than half of whom are renters), and the number of affordable housing units kept declining. But solutions seemed out of reach—there was no rent control, and the new houses and apartments being built generally catered to high-income residents, out-of-towners seeking holiday homes, or those looking to rent out units to the tourists who were flocking to Portland in droves. In the years following the growth of Airbnb, roughly 4 percent of all rental units were removed from the long-term market, according to research by housing advocates—enough to further constrict an already tight market. Rents began going up in the early 2000s, and the trend has only accelerated.

For Matt Walker, a geophysicist who had studied as an undergraduate at the University of Southern Maine in the early 2000s, the difference was tangible. While at USM, he had worked at a parking garage, earning a paltry wage that nonetheless enabled him to rent a lovely one-bedroom apartment on the red-brick-lined streets of the city’s old downtown. He had gone on to graduate work at UCLA and lived in Southern California for much of the next decade. When he returned to Portland to take a job at USM, he was stunned by how expensive housing had become.

Walker was now a professor, with contracts to work on NASA projects exploring the solar system for planets and moons that potentially could host life. But he couldn’t afford to live in the area he had rented in as an undergraduate. Instead, he found a small apartment in another neighborhood. It was bedeviled by fire-safety issues, with its windows illegally sealed shut, its trash uncollected, and rats running riot. When he complained, in the early months of the Covid-19 pandemic, he was served with an eviction notice. “I was given 30 days to move,” he recalls. “I have fantastic credit, a PhD, and I could not find a place.”

The arrival of Covid in early 2020 had made a bad situation worse. Suddenly, hordes of remote workers fleeing the larger East Coast cities were finding refuge in Portland—and, in the process, driving up rents. Sydney Avitia, who was earning roughly $35,000 a year at the start of the pandemic working as a community organizer at Maine People’s Alliance, bounced from one rental to the next in search of affordable housing. Avitia eventually ended up in a shared two-bedroom, increasingly aware that “the housing crisis is going to get so much fucking worse.” When city shelters were emptied out to prevent the spread of Covid, hundreds of people ended up camping on the streets, many of them ultimately taking part in an 18-day Occupy-like protest outside City Hall to draw attention to their plight. Months before the federal eviction moratorium went into effect, Avitia helped found the group Maine Renters United, aiming to build up “grassroots power.” In the early months of the pandemic, MRU pushed for local rent freezes as members went door-to-door canvassing for the creation of tenants’ unions to advocate for those at risk of eviction.

Although Walker, like Avitia, eventually did find another place to live, the experience changed him. If it was a struggle for him, how much worse must things be for people with less income and less social capital? Walker joined the Democratic Socialists of America in 2020. He also joined a tenants’ union in his new building, in the arts-and-restaurant district around Congress Street. And after the DSA-backed housing initiatives passed, he volunteered to serve on Portland’s newly established Rent Board, hearing complaints brought by tenants against their landlords. “I’ve helped people save, in my building alone, nearly $100,000,” he says.

Historically, Portland’s mayor has held relatively little centralized power, with much of the daily decision-making delegated to the unelected city manager. Until recently, the mayor had been appointed by fellow councilmembers rather than directly elected, the result of a compromise in the 1920s between the city’s elites and a surging Ku Klux Klan, which feared that direct elections would empower Portland’s growing ethnic communities. That changed in 2011, when the city charter was amended to provide for direct mayoral elections; then, in 2015, a onetime state legislator named Ethan Strimling was elected to the position. Strimling, who had traveled to El Salvador and Nicaragua as a young man in the mid-1980s to perform street theater, was a progressive with grand ambitions for reimagining the city, above all a desire to tackle the affordable housing shortfall. He was smart as a whip, charismatic, and, with his thick, wavy hair and muscular build, could have passed for a movie star.

Yet despite the new mayor’s best intentions, the city’s homeless numbers spiraled ever higher in the years leading up to the pandemic—as did the rents that landlords were charging. Moreover, while Strimling’s policy instincts were strong, he was less secure in his dealings with other councilmembers and the city manager’s office. He was good at imagining public policy but, as even some of his closest allies acknowledged, rather less competent at doing the politicking needed to make those changes a reality. Time after time, he’d propose changes only to have them shot down. Seemingly by the day, the mayor’s relationship with his colleagues in the city government became more abrasive.

By 2019, Strimling was being hammered in the polls and the local media. The Portland Press Herald led the charge, portraying his mayorship as a failed experiment in radical governance. Strimling overwhelmingly lost his reelection bid, and his replacement, Kate Snyder, promised to dial down the political heat. It seemed to many that when it came to housing issues, City Hall would return to the do-nothing politics of the pre-Strimling era. For Strimling, though, the loss turned out to be liberating, allowing him to push for radical policy reforms from the grassroots up rather than the City Council down. No longer constrained by the dysfunctional city government, the ex-mayor threw in his lot with members of the local DSA branch and took his ideas about housing reform directly to the people.

In early 2020, there were several hundred people on the local DSA mailing list, with dozens willing to put in considerable time and effort on political campaigns. Laid off from their jobs during the pandemic, many of them turned to organizing: Masked up and socially distanced, they went out and talked to voters, launched letter-writing campaigns, and wrote op-eds.

As those early months of the pandemic ground on, these activists amped up their work, building on the organizing around housing issues that had been going on in the city for at least three years—though those efforts had not always been successful. In 2017, when Strimling was still mayor, the advocacy group Progressive Portland had tried to get voters to pass a rent control ordinance. “In order to get anything done in Portland, you have to work around and against the City Council and city staff,” says Steven Biel, a cofounder of Progressive Portland. There was “such a thirst in the city for progressive activism” in the wake of Donald Trump’s election, he recalls, that it seemed like the perfect moment to call for rent control. At the same time, Progressive Portland also pushed the City Council to pass a stronger inclusionary zoning ordinance, which would mandate that one out of every 10 new housing units be designated as affordable. But it wasn’t to be. Their opponents outspent and out-organized them; the city stonewalled on inclusive housing; and the initiative went down in flames. The result wasn’t even close: In a low-turnout election, 64 percent of voters opposed the measure.

Instead of throwing in the towel, activists got back to work, putting in long hours knocking on doors, talking to voters, and doing good old-fashioned campaigning. Three years later, with support from Strimling and the growing DSA chapter, advocates were ready to try their luck with housing initiatives again, banking on high voter turnout in a liberal city in a crucial election year. They were going to shoot not only for a strong rent control policy, but also for a Green New Deal that would require that 25 percent of new housing units be designated as affordable, as well as a living wage on construction sites and the expansion of apprenticeship programs that trade unions had long seen as critical for developing the next generation of skilled workers. On top of all that, they hoped to rein in Airbnb. They winnowed down their ideas to five initiatives, across a range of policy issues, to put before voters in what they rightly gauged would be a massively high-turnout election.

“We are building toward something,” says Wes Pelletier, a 33-year-old software developer and organizer with the DSA. For the past three years, Pelletier has opened up his second-floor living room in the 19th-century wooden house where he and his wife, Amy, rent an apartment to campaign meetings. The organizers—many of whom had been drawn into politics by Bernie Sanders’s presidential run in 2016—held weekly masked meetings on the green upholstered sofas, with the couple’s gray cat, Sardine, stalking past the large vinyl record collection and the brick-façade fireplace.

They were an eclectic bunch: Patricia Washburn, an ex-journalist, now confined to a wheelchair by lipedema, who worked as a technical writer; Jack O’Brien, an associate professor of mathematics at Bowdoin College specializing in statistics; Kate Sykes, who had worked in medical education. In the words of their ally Jason Shedlock, the president of the Maine State Building and Construction Trades Council and an executive member of the Maine chapter of the AFL-CIO, they were “this merry band of misfits who weren’t going to take no for an answer.”

In the depths of the pandemic, a slew of initiatives won majority support, creating a rent control system for the city and locking in a set of affordable housing mandates and Green New Deal policies aimed at shoring up environmental and labor standards for construction projects. The initiatives created a Rent Board to adjudicate complaints against landlords as well as pathways to an infusion of cash for the decades-old Housing Trust Fund, which currently has about $9 million to be used as seed money for affordable housing projects. Some local developers are already putting forward plans for high-density nonprofit and affordable housing using this fund. Progressive measures not related to housing, including a minimum-wage increase, also got the nod from voters.

“It seemed to me it was pie in the sky, and they wouldn’t be able to get it done,” Biel recalls. “What DSA showed was the public was far more progressive—especially on housing policy—than even I thought.” With the pandemic scrambling the world of business-as-usual, voters came out in droves, not only to reject Trump but to stamp their mark on Portland’s housing market.

Sitting in the iconic Becky’s Diner on the Commercial Street waterfront, Sykes says that the passage of the progressive initiatives “was basically a beatdown of establishment politics in Portland. It was the turning point for DSA. We passed rent control, raised the minimum wage to $15 per hour, banned the use of facial surveillance technology by the police. We passed the Green New Deal. And we tried to ban short-term rentals.” That last initiative, which would have added slack to an unsustainably tight rental market, lost by only a couple hundred votes.

“It was a perfect storm,” Sykes says of the 2020 campaign. “We knew, strategically, exactly what we were doing.” The run of victories continued in 2022, when voters revisited the rent control provisions and eliminated loopholes. Activists notched another win this past June, when, with 67 percent of the vote, they easily defeated an effort by landlords to roll back the rent control provisions.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Despite these back-to-back-to-back victories, however, Portland remains divided over the efficacy of the reforms. Its housing market is still far from stabilized, and homeless encampments dot the city’s periphery. Developers and landlords argue that the new regulations—which they have taken to calling a “cluster bomb”—make it impossible to turn a profit and thus discourage the building of new housing as well as the upkeep and modernization of existing buildings.

Culley, the developer, worries that the inclusionary zoning laws could tamp down development and push housing further out of reach for the city’s most vulnerable populations. The only large developments to get off the ground since the passage of the new rules mandating that a quarter of units be devoted to affordable housing, he says, are those backed by federal subsidies. That includes the much-touted Elm Street development, an 800-unit project scheduled to break ground in the coming months, which was made possible, he says, by a $30 million federal grant using onetime Covid relief funds. With interest rates hovering at around 7 percent, Culley adds, anything that cuts into developers’ profit margins will drive them away.

Brit Vitalius, the president of the landlord-backed Rental Housing Alliance of Southern Maine, recently spent $25,000 renovating a rental unit he owns after its longtime tenant died. But now he can only raise the rent by the rate of inflation plus the additional 5 percent allowed when a new tenant takes over the property. It isn’t enough, he insists, to cover the renovations. “So, I’m screwed,” he says. “I’m going to sell my building.” Activists counter that the new rules need time, that they are starting to show results and would be working a lot better if the city weren’t doing everything in its power to ignore them. In the face of this intransigence, a growing number of renters are forming tenants’ unions, hoping that their collective power and their ability to present cases to the new Rent Board will drag more landlords into compliance and force the city to order refunds to tenants whose landlords illegally raised the rent by more than the formula approved by voters allows. “It does seem as if rent control is keeping rents lower,” says O’Brien, the statistician, sitting at an outdoor table in the rain at a Colombian café. “But rent control does not cure a housing crisis—it is a tool to blunt some of its effects.”

The authors of the reforms remain optimistic. Hoping to parlay the momentum into something bigger, Sykes is running for a spot on the City Council, one of several progressives aiming to shift the city government leftward to meet the increasingly radical Portland electorate. Among their goals: to pass a version of Seattle’s Measure 135, which set up a public housing development corporation, potentially backed by bond money, to allow the city to build large numbers of public housing units that would, presumably, once the bonds are paid off, see smaller and smaller rent increases and become increasingly more affordable to tenants—an American version of the social housing models implemented over several generations in Vienna and Singapore.

The housing shortage, Sykes believes, is part of a spectrum of policy failures that she calls a “polycrisis.” The word “crisis” comes from the Greek medical term for the point at which a patient either starts to recover or rapidly dies. That, she says, is where America is today. The approach taken in Portland shows that with outside-the-box thinking, there’s room for the patient to recover: “For a little city, we’re really punching above our weight.” For Sykes, the passage of the initiatives is not an endpoint. “When you pass legislation, it’s not the be-all and end-all of it; it’s really the beginning of the organizing.”

That’s something that Vitalius fears. “We fought four rent control referenda—won the first back in 2017 and lost the next three,” he says. “Personally, I’m not going to fight anymore. Portland seems to be very content with DSA writing our housing policy.”

For many of the region’s developers, the inclusionary zoning ordinance was ill-advised. “When you start pressing these levers, if you press too hard on inclusionary zoning, then you’re going to get nothing,” says Culley, who continues to favor intervention at the federal rather than the municipal level. Already pressed by skyrocketing interest rates, he adds, the developers can’t make a profit if they either have to reserve 25 percent of their units for renters who make less than 80 percent of the area median wage or have to pay penalties into the housing development fund. Culley wants more flexibility, arguing that inclusionary zoning requirements need to be modified to reflect the changing costs of borrowing that developers face. At a city-run “housing supply boot camp” in January, developers pushed back against the new rules, claiming, according to notes from the event, that inclusionary zoning requirements “have made it virtually impossible to build new housing of 10 units or more without public subsidy.” They bemoaned “a lack of understanding among members of the public, and possibly elected officials, about the realities of the development process.”

Strimling, who counts Culley as a friend—the two occasionally meet for lunch—disagrees. He points out that, as of the end of 2022, 1,200 units were under construction. “For a city with 18,000 [rented] apartments, that’s a pretty good deal,” the ex-mayor says, brushing aside Culley’s claim. And, he continues, with the development underway on Elm Street, to be built with union labor under the terms of the Green New Deal initiative, “there’s a shit-ton more in the pipeline.”

Wes Pelletier, the DSA organizer, is still amazed by how much the bare-bones campaigns from 2020 to 2023 accomplished—and how their message has resonated with voters—but he is also somewhat cynical about the city’s willingness to play ball. “The city has a lot of data on landlords who are in violation of the law,” he says. “And they will not even send a letter to the landlords and the tenants about violations.” Still, he remains optimistic that rent increases are finally starting to slow and that tenants’ unions are beginning to use the new laws to level the playing field in favor of renters—that, despite the stonewalling efforts of the city government, people power will ultimately triumph.

Even though the city administration has shown little interest in aggressively enforcing the new ordinances, “the data shows that the rent controls are genuinely working,” says O’Brien, who started campaigning for a rent control initiative back in 2017. “Rents are not spiking. Most landlords are in compliance…. Portland dodged an enormous bullet. The housing situation was bad, and we implemented rent control just before things got a whole lot worse.”

Supporters also point out that large new building projects—such as the one partly slated on what is currently a large parking lot on Elm Street, in a poor neighborhood heavily populated by recent immigrants and with the offices of many social service agencies, backed by federal ARPA funds—include more affordable and low-income housing units. And they trumpet the fact that pay rates and labor conditions for construction workers on new projects have also improved. “People aren’t afraid to try things out here in Portland,” says Shedlock, whose Building Trades Council will be among those building the new developments at Elm Street and elsewhere. “These are time-release victories that play out over years, not days.”

Portland’s Department of Planning & Urban Development’s 2022 housing report shows that the city is on track to significantly exceed the production of housing units envisioned in its 2017 project, Portland’s Plan, which set a goal of building 2,557 new units over the next 10 years. Recent data suggest that number will be reached by 2025, with more than 1,000 additional units completed by 2027, with the majority in multi-unit buildings. On a per capita basis, Portland is currently building at a faster rate than New York, San Francisco, and Boston. Nearly one-third of the new units approved in 2022 are listed as affordable housing for households earning between 60 and 100 percent of the area’s median income.

Portland’s new housing ordinances have been on the books less than three years. That many developers loathe the new rules is a given. Yet just because these reforms might suffer teething problems is no reason to give up on the prospect of meaningful change. Ten years from now, looking back at what Sykes calls the polycrisis of the early 2020s, we may see the Portland revolt against the housing status quo as a turning point—the moment when a sick housing market started, slowly, to get back to health.

“It’s a hugely exciting time in Portland and across the state,” says Shedlock, sitting in the Laborers’ International Union New England Region’s Maine office, where he is regional organizer. The word “solidarity” is tattooed down his left arm. “The voices of working families, they’ve learned how to grab that megaphone,” he continues. “And they’re not going to let it go at this point.”

More from The Nation

Donald Trump Is the Authentic American Berserk Donald Trump Is the Authentic American Berserk

Far from being an alien interloper, the incoming president draws from homegrown authoritarianism.

If Democrats Want to Reconnect With the Working Class, They Need to Start Listening to Unions If Democrats Want to Reconnect With the Working Class, They Need to Start Listening to Unions

The Democrats blew it with non-union workers in the 2024 election. Unions have a plan to get the party on message.

What Was the Biggest Factor in Kamala Harris’s Defeat? What Was the Biggest Factor in Kamala Harris’s Defeat?

As progressives continue to debate the reasons for Harris's loss—it was the economy! it was the bigotry!—Isabella Weber and Elie Mystal duke out their opposing positions.