The Fate of the Senate Depends on Jon Tester

Senator Jon Tester is the last Democrat holding statewide office in Montana. Can he save his seat and help keep the Senate blue?

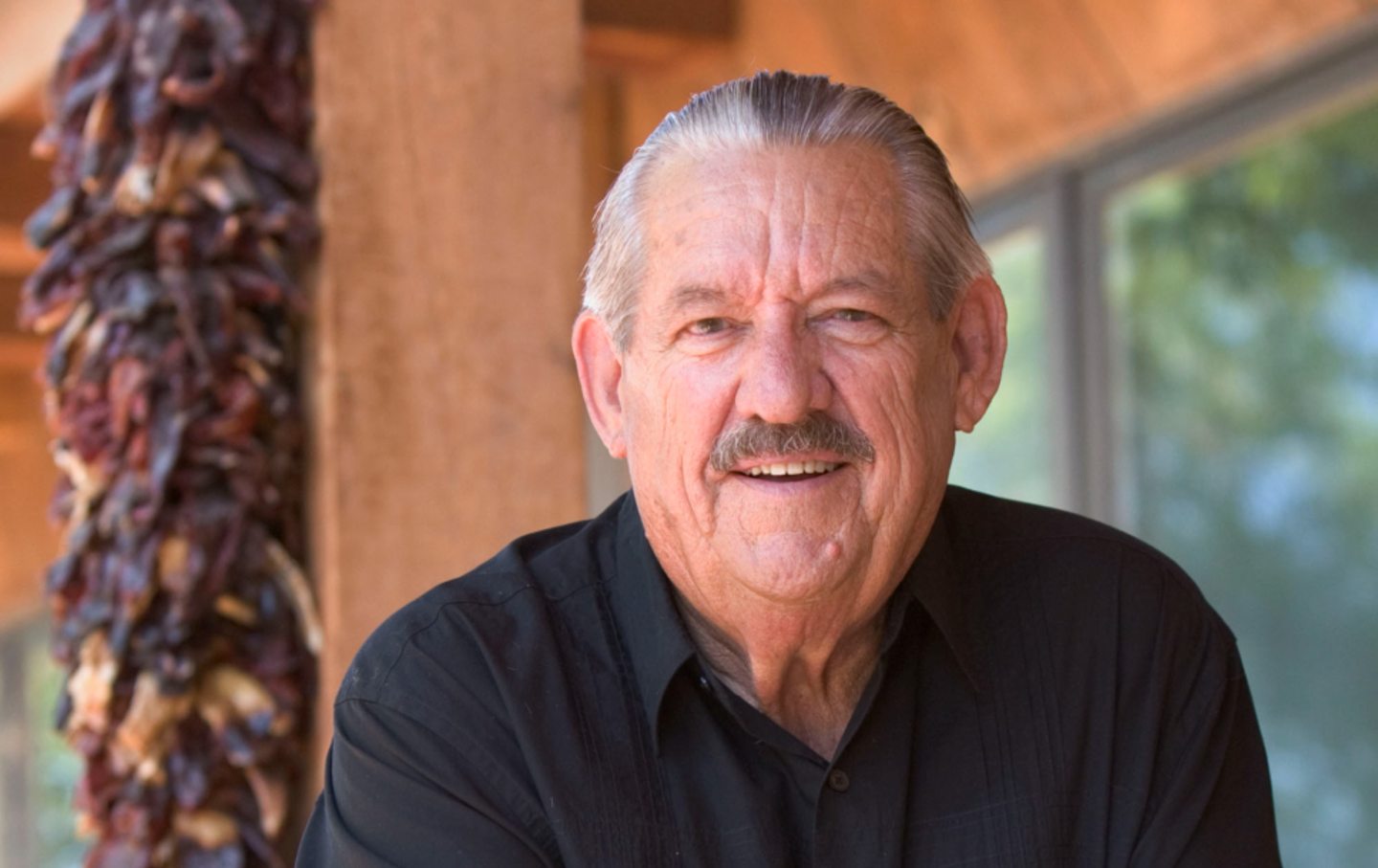

(Kent Nishimura / Getty Images)

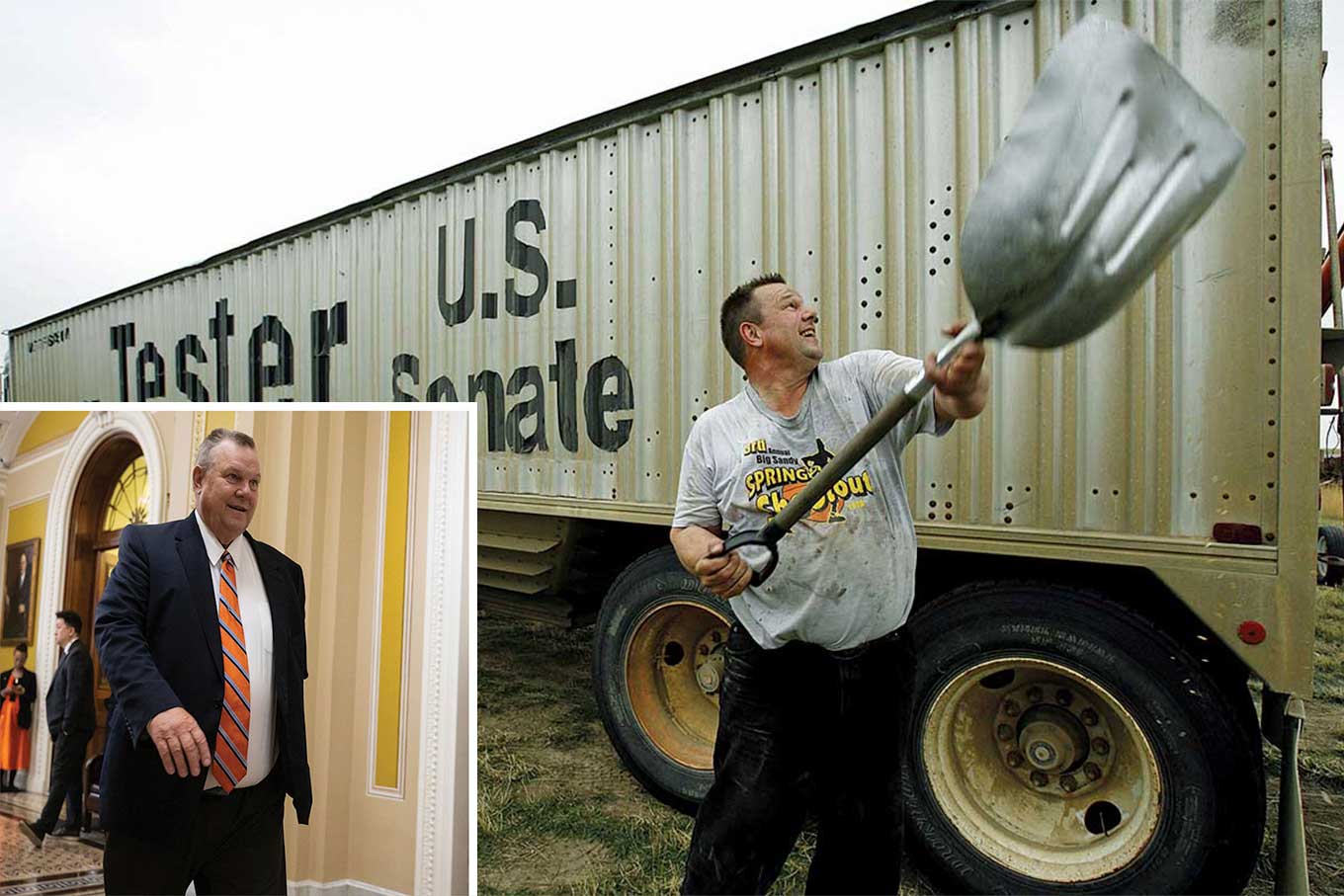

On November 7, 2006, Senator Jon Tester gathered with his campaign team at the Heritage Inn in Great Falls, Montana, a former smelter town with a population of 60,000 clustered around five hydroelectric dams on the Missouri River. It was election night, and the mood was ebullient. The upstart campaign was about to upend the balance of the US Senate.

“We had a stage with balloons, and everyone was ready for a big party,” remembered Bill Lombardi, Tester’s former state director, “but the AP wouldn’t call it because it was so close. So we told everyone to go home.”

At the time, Tester was just a third-generation farmer and butcher from Big Sandy, a town with 600 people, three bars, and one grocery store. He was also a former music teacher and school board member who had worked his way up in Montana politics to become president of the state Senate. Still, few Montanans knew his name when he entered the race.

By contrast, his opponent, Conrad Burns, was an 18-year incumbent in the US Senate who sat on the powerful Appropriations Committee. A Marine Corps veteran and former cattle auctioneer, he had a history of delivering money to a rural state that consistently ranks among the top 10 most federally dependent in the nation. Most Montanans knew his name.

But Burns had a major liability: He was one of the lawmakers whom the disgraced lobbyist and convicted felon Jack Abramoff trusted to deliver federal dollars to his clients. This liability surfaced in 2004, when Burns earmarked $3 million for the Saginaw Chippewa Indian Tribe, an Abramoff client, to build a new school. The Michigan-based tribe contributed thousands to Burns’s PAC both before and immediately after that appropriation, drawing criticism in the state and national press.

“Every appropriation we wanted [from Burns’s committee], we got,” Abramoff told Vanity Fair in April 2006. “Our staffs were as close as they could be.”

On election night, Lombardi stayed up to watch the returns, and when the sun came up, a wheat farmer was leading one of the most powerful senators in the West by just over 1,000 votes. Ultimately, Tester won by 3,562 votes, less than 1 percent of the total.

“We won because of his authenticity—that agrarian populism, a person who’s tied to the land,” Lombardi told me. “Montanans still have that libertarian-populist streak. They don’t want these fake cowboys.”

Today, the battle to control the US Senate will once again be fought in Montana and a few other swing states, with at least seven contested races for seats currently held by Democrats and one independent. The challenge for Republicans is that Tester hasn’t changed. He’s still the same guy who beat Burns: a scandal-free farmer from Big Sandy.

The challenge for Democrats, though, is that Tester’s role has been reversed. Now he is the 18-year incumbent vulnerable to the time-tested insult of “career politician.” More important, Montana isn’t the same place where Tester won 18, or even six, years ago. Like so much of rural America, it has been transformed by the polarization of major media outlets and the nationalization of politics. Local newspapers keep shutting down or laying off reporters, and now more Montanans learn about current events from Fox News than any other news outlet. Montana, in the 2016 and 2020 elections, was roughly 11 points more Republican than the nation overall.

Today, Tester is the only remaining statewide officeholder in the Democratic Party, and he’s running for a fourth term against Tim Sheehy, a pro-Trump Navy SEAL with no political history. The question this year is whether Tester, who has regularly defied pundits and outperformed the polls, can muster one more win.

On May 19, I drove to Bozeman to interview Tester, who was in town to shoot a campaign ad. It was 40 degrees when I arrived, and sleet was pelting the front windows of the ELM, a music venue near downtown. Inside, Tester mingled with 20 or 30 veterans who’d driven from all over the state to promote his work on the Senate Veterans’ Affairs Committee. Wearing a plaid Carhartt shirt and blue jeans, the working farmer with his famous flattop posed for photos in front of a huge American flag.

He’d been on his tractor planting alfalfa, peas, and hard red spring wheat early that morning before boarding a plane to Bozeman, and he was anxious to finish the job before returning to DC. So the campaign invited me to join him for the 20-minute drive to the regional airport in Belgrade. After he ordered three beef soft shells at a Taco John’s drive-through, I asked him about our country’s defining political trend: polarization.

“Obviously, I don’t think it’s healthy,” Tester said, crushing a taco wrapper in his right hand. He had lost three fingers on his left hand in a meat grinder when he was 9 years old. “It keeps us from getting work done.”

He brought up the border security bill that was introduced in the Senate and voted down by House Republicans in mid-April as an example of lawmakers voting against their own party’s policies in order to deepen polarization on a politically advantageous issue. The $118 billion legislation—which raised the ire of several members of the Democratic Caucus, who felt that the bill was doubling down on punitive Trump-era policies—would have added 1,500 Border Patrol agents, increased ICE’s detention capacity, and created an emergency authority to deport migrants before they could apply for asylum.

“It’s interesting—what people don’t remember at all is Trump said, ‘Kill this bill and blame me for it.’ He actually said that, [because] they wanted it as a campaign issue, and they’re using it as a campaign issue, record be damned.”

I asked whether it’s possible to get a majority of Montana voters to appreciate the nuances of what he called a “missed opportunity” when Republican ads on illegal immigration occupy every commercial break.

“Well, you’ve got to say it over and over again, and hopefully they’ll believe it,” he replied, “but the truth is, they don’t look at the fact that I have voted for a wall in certain areas. I have voted for additional manpower. I have voted for additional funding.”

I could hear some frustration growing in Tester’s voice as he detailed his own record on the issue. “The truth is, they try to pigeonhole people into all these positions when in fact they’re not accurate.”

As a Democrat in a Republican state, Tester is sensitive to being pigeonholed. In fact, he’s been liberal on issues with cross-party appeal for Republicans—he’s a champion of labor and a protector of public lands—and conservative on issues with cross-party appeal for Democrats, namely immigration and foreign policy. And this balancing act has frequently put him at odds with progressive members of his party.

During his first term, Tester voted against the DREAM Act, which would have granted conditional US residency to qualifying undocumented high school graduates. The bill fell just five votes short of the 60 needed for passage. He’s also been a reliable vote for defense funding and has only occasionally opposed US military action abroad, voting against air strikes in Syria but supporting the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Lately, Tester has dismissed calls for a ceasefire in the Israel-Hamas war, which has killed more than 38,000 Palestinians, including more than 15,000 children, and about 800 Israeli civilians. In March, when ceasefire supporters interrupted his speech at a Democratic gala in Helena, the crowd started chanting, “Let’s go, Jon!” After sheriff’s deputies removed the protesters, Tester quipped, “Isn’t it great to be popular?”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →During the ride to the airport, I asked him why he’d decided to run for a fourth term, and he returned to the topic of pro-Palestinian demonstrations. “What drives me crazy is, we get protested by 10 or 12 of these kids that are ‘pro-Palestinian’ or ‘pro-Hamas’ or ‘antisemites’ —I don’t know what the fuck they are,” he said. “But they come in in their mid-20s, maybe 30, and they actually think that if they defeat me in this election, I’m going to cry about it, when in fact the only reason I’m running is for them.”

He explained, “I’m trying to set it up, truthfully, so that we have clean air and clean water, and we’re moving into the 21st century in a way where our economy is going to give opportunity to our kids and our grandkids. And that shit doesn’t happen by accident; it happens by people thinking forward.”

Because the Democratic Party leadership has given him influential committee assignments, Tester has had the opportunity to put such thoughts into action, and he has written and passed several bipartisan bills during a period marked by legislative gridlock.

In 2009, just three years into his first term, Tester was given a seat on the Senate Appropriations Committee, and in 2014, he cosponsored and passed the Rocky Mountain Heritage Act, which protects 275,000 acres of wildlife habitat south of Glacier National Park, an area long threatened by oil and gas development.

As one of the 10 senators who wrote the 2021 infrastructure bill, Tester has channeled hundreds of millions of dollars into clean-water projects for rural communities in Montana and the state’s Indian reservations. And last year, in a bid to address the rising cost of housing in Montana, he secured $225 million for the PRICE grant program, which funds the construction of factory-built homes in eligible communities.

As the chair of the Senate’s Veterans’ Affairs Committee and the Appropriations subcommittee on defense, he’s also expanded healthcare for a new generation of veterans. In 2022, he passed the PACT Act, the largest expansion of Veterans’ Affairs health services in decades, which grants thousands of veterans exposed to toxic chemicals access to VA health benefits. Last year, he successfully introduced the Veterans’ Compensation COLA Act to ensure that benefits for veterans with service-connected injuries keep pace with inflation.

Still, legislative achievements have a limited effect on voters’ partisan affiliations, which are becoming less flexible each year, particularly for Republicans, whose partisan preferences have calcified since Donald Trump effectively took control of the GOP. Without trusted local news sources to inform voters, actual policy outcomes, such as increased funding for veterans, may influence them less than inflammatory attack ads.

In April, the conservative One Nation PAC purchased $15 million in television ads to paint Tester as soft on immigration, and that investment has paid dividends. Undocumented immigration is arguably the top issue for Montana Republicans, even though the state is more than 1,000 miles from the southern border.

Tester, though, is reluctant to accept polarization as a foregone conclusion, even on issues like immigration, perhaps because he’s defied the trend more than once. In 2012, when Mitt Romney defeated Barack Obama by a 14-point margin in Montana, Tester beat his challenger, Representative Denny Rehberg, by nearly four points. Then he won by nearly the same margin in 2018, two years after Trump vanquished Hillary Clinton by 20 points.

“I think the ticket-splitting stuff is still going to happen,” Tester said, “because I think Montana is still a small enough state where [the voters will] look and say, ‘All right, what’s the dude done, what’s he done that’s helped my life?’ And I think they’re going to—” He paused, searching for an end to the sentence. “I think it’s going to be fine.”

If things once again work out fine for Tester and his supporters, it will be because Montanans’ favorable views of the farmer outweigh their partisan ties to Trump. In several polls taken over the fall and winter, that appeared to be the case, but the most recent poll, from early July, shows Sheehy with a 5-point lead, raising the question of whether Tester’s track record and personal appeal can suppress voters’ partisan ardor.

During Tester’s last reelection campaign, authenticity was a decisive theme. His opponent in 2018 was State Auditor Matt Rosendale, a real estate developer from Baltimore who moved to Montana in 2002. Early in the race, the Tester operation dubbed him “Maryland Matt” and pounded his slow-moving campaign with television ads challenging his Montana bona fides. Tester won by nearly 18,000 votes, the largest margin of his career.

But he won’t have the pleasure of running against Rosendale this year. On February 9, Trump endorsed Sheehy hours after Rosendale announced another Senate bid, ending a rancorous debate within the Montana GOP over who should go toe-to-toe with Tester.

Sheehy, a millionaire from Minnesota, was hand-picked by Montana Senator Steve Daines, the current chair of the National Republican Senatorial Committee. Sheehy announced his bid last summer and has been running full-on for a year. By the end of March, he’d already spent nearly $1.5 million of his own money in a race that will set a record for political spending in Montana. And he’s using these resources to highlight his support for a range of issues, including tighter border security, ending access to abortion, and defending the Lord’s Prayer in public schools.

“Tester has had weaker opponents in the past,” Jessica Taylor, the Senate and governors editor at the Cook Political Report, told me. “I mean, this race might be over if Rosendale was running with his past baggage and anemic fundraising.”

Anticipating this outcome, Tester’s campaign launched television ads and began talking to voters earlier than in previous cycles. In March, it also announced a Native vote program to connect with Indigenous constituents who have been the target of voter-suppression efforts by Republicans in the state Legislature. At 6.6 percent of Montana’s population, Indigenous people represent a powerful bloc in the Democratic base, and Tester’s campaign plans to spend at least $1.2 million to reach them—more than twice what it spent last cycle.

This level of early spending confirms the expectation that Sheehy would be a more formidable opponent than Rosendale.

Sheehy, 38, grew up in a multimillion-dollar lake house in the Twin Cities suburb of Shoreview, Minnesota. He graduated from a private high school in 2004 before enrolling in the US Naval Academy. In 2015, he was awarded a Bronze Star for helping to evacuate a wounded member of his unit while serving in Afghanistan three years earlier.

Sheehy moved to Bozeman after receiving a medical discharge. In 2014, he founded Bridger Aerospace, an aerial firefighting company that relies on government contracts for 88 percent of its revenue and reported $77 million in losses last year. In 2020, Sheehy bought three adjacent ranches in the Little Belt Mountains and started to raise cattle.

This latest business venture, named the Little Belt Cattle Company, has been an easy target for Tester. Last summer, Business Insider reported that a campaign photo of Sheehy posing by a barbed-wire fence was actually taken in Kentucky. More recently, Sheehy came under fire for selling private hunting trips on the ranch for $12,500 each.

“It’s not just that Tim Sheehy moved here from out of state,” said Shelbi Dantic, Tester’s campaign manager. “It’s that he is a self-interested multimillionaire who does not understand or care about the Montana way of life and is trying to change our state into a playground for rich transplants like him.”

Historically, this line of attack has been the most effective in Tester’s political playbook. But the level of damage incurred by opposing candidates also depends on the legitimacy of their claim to be someone most Montanans admire. When Sheehy advertises a rural upbringing and portrays himself as a rancher, he risks being seen as just another rhinestone cowboy. His military service, however, could place him on terra firma in a state with the fifth-highest number of veterans per capita in the country.

“The GOP has a history of getting behind a wealthy candidate who has recently moved to the state, and I do think there is a vein of that frustration in Montana,” Taylor said. “But I guess I reserve judgment on whether that works, because Sheehy moved there after finishing his military service, which could negate some of that.”

Ultimately, Sheehy’s ability to convert his military service into political capital depends on how well his actual record matches his portrayal of it to voters, and there are already some inconsistencies. In December, Sheehy’s campaign posted a video of him at an event telling supporters that he still had a bullet lodged in his right forearm “from Afghanistan.” But in April, The Washington Post reported that Sheehy sustained the wound when he accidentally shot himself in Glacier National Park in October 2015. And in his 2023 memoir, Mudslingers, he provides two conflicting explanations for the injury.

Sheehy’s campaign minimizes communication with reporters and strictly controls media queries. The campaign has no phone number or physical address. Katie Martin and Jack O’Brien, communications consultants for Sheehy’s campaign, did not reply to multiple requests for comment. Calls to the Montana Republican Party and messages sent through its website were also not returned.

Aside from past donations to GOP candidates, Sheehy has no significant political history. This void has allowed him to reflect the hopes of the Trump wing of the party without offending moderates. Some moderates, though, are beginning to voice their dissent.

The state’s former Republican governor, Marc Racicot, who served from 1993 to 2001, is a leading critic of Sheehy and other far-right Republicans. It’s hard to question his conservative credentials: Racicot chaired the Republican National Committee from 2002 to 2003 and led George W. Bush’s presidential reelection campaign. “I’ve known Jon since he first reported for his job at the State Capitol,” he said. “I have a high opinion of his ability to act independently and do what he thinks is right.”

As for Sheehy, Racicot said, “The fact that he moved to Montana recently doesn’t bother me. What bothers me is that he moved here simply to be the vehicle for Donald Trump’s will, which is a will to remain in power. That’s all that Tim Sheehy has claimed as a merit badge: to be a loyal acolyte to Trump.”

Yet most rank-and-file Montana Republicans disagree. In a state that Biden lost by 16 points, Sheehy’s fealty to Trump is likely enough to earn their support.

For liberal and moderate Montanans, the extent of this rightward shift merits close attention. Not long ago, things were trending in the opposite direction.

Tester’s surprise victory over Burns was part of a surge of Democratic support among Montana voters, who have split their ballots for generations. In 2008, they narrowly favored John McCain over Obama by 11,000 votes, but Democrats held both of Montana’s US Senate seats and all six statewide offices, and they had a 50-50 tie in the state House of Representatives.

Four years later, voters reelected Tester and five more Democratic incumbents to statewide offices. But there were signs that a change was underway. In 2012, Montanans chose Romney over Obama by nearly 65,000 votes, an 11-percentage-point swing from 2008. Since 2012, Democrats have lost 21 out of 23 statewide and federal races, and Republicans have held the majority in both state legislative chambers for 14 years.

“Tester is the last man standing, and what used to be a purple state is now clearly a red state,” said Rob Saldin, a political science professor at the University of Montana and a senior fellow at the Niskanen Institute in Washington, DC.

More on Montana politics:

And these partisan trends are likely to continue. Montana has the sixth-highest percentage of voters 65 years and older, a group that is increasingly likely to vote a straight ticket in the state. In 2016, there was an 18-point difference between the highest- and lowest-performing Democrats. Four years later, every Democratic candidate ran within six points of the rest, marking a dramatic decline in crossover voters.

These are foreboding figures for Tester, who held favor with older voters in the past but seems to be losing ground. Although his 61 percent approval rating among Montanans remains one of highest in the country, his approval rating among Republicans has plummeted from 42 to 22 percent.

“Obviously, you can’t find a better example of a candidate who is able to distinguish himself from the national party, but there are some really big structural forces at play here,” Saldin said. “National issues matter more than local issues now. The urban-rural divide has really been exacerbated in recent years. Then there are the forces of polarization of politics. All of these things are way more intense than in 2018, and they all work to the advantage of the GOP in Montana and, insofar as the Senate is concerned, the entire nation.”

On these points, Taylor, the Cook Political Report editor, agrees. “I think this is Tester’s toughest race because of the environment he’s running in,” she said. “On paper, he’s the most endangered incumbent in the Senate. But I think Tester is a talented politician, and you can’t count him out. If anyone can outrun Biden by 10-plus points, it’s probably Tester.”

Of course, it’s not just Tester who’s in danger. If Sheehy wins, every policy that depends on a Democratic majority in the Senate to become law would also be imperiled.

“Democrats cannot afford to lose a single senator,” Taylor said. “And even if they don’t lose a senator but Trump wins, then Trump’s VP will be the tiebreaking vote.”

This possibility is not lost on Tester, who voted for the Inflation Reduction Act, enabling Vice President Kamala Harris to cast the tiebreaking vote on a bill that the International Monetary Fund calls “the most significant piece of climate legislation in the history of the US.”

“I do this in every election,” Tester told me as we neared Belgrade. “You always think of what you’re going to do if you win, and you think about what you’re going to do if you lose.”

As we were driven by a campaign staffer, Tester gazed through the rain that was drumming the passenger window. “I don’t think I’m going to have a lot of crying for myself. I’ll have some crying for the country, and I’ll have some crying for my kids and my grandkids—but for me, life will get markedly better if I don’t get back to the Senate. Why? Because I’ll have some fucking time.”

As we pulled up to the hangar, I could see the tiny single-engine prop plane that would soon be buzzing high above the wheat and barley fields toward Big Sandy. In a few hours, Tester would be back on his tractor.

“Ray Peck, ya know, was the guy that got me hooked into politics,” he said, referring to a former school superintendent from Big Sandy who recruited him to run for office in 1998. “When I told Ray I was going to come home every weekend to farm, he said, ‘You’ll be dead before the end of your first session—no human being can make that trip every weekend.’”

“Well,” Tester said, “I’ve done it for 18 years, and if I get reelected, I’ll do it again.”

Correction: A previous version of this article stated that 1,100 Israeli civilians had been killed during the Israel-Hamas war. About 800 civilians have been killed.