Making Sense of the Fascism Debate

A Rorschach test for understanding what is ailing American society.

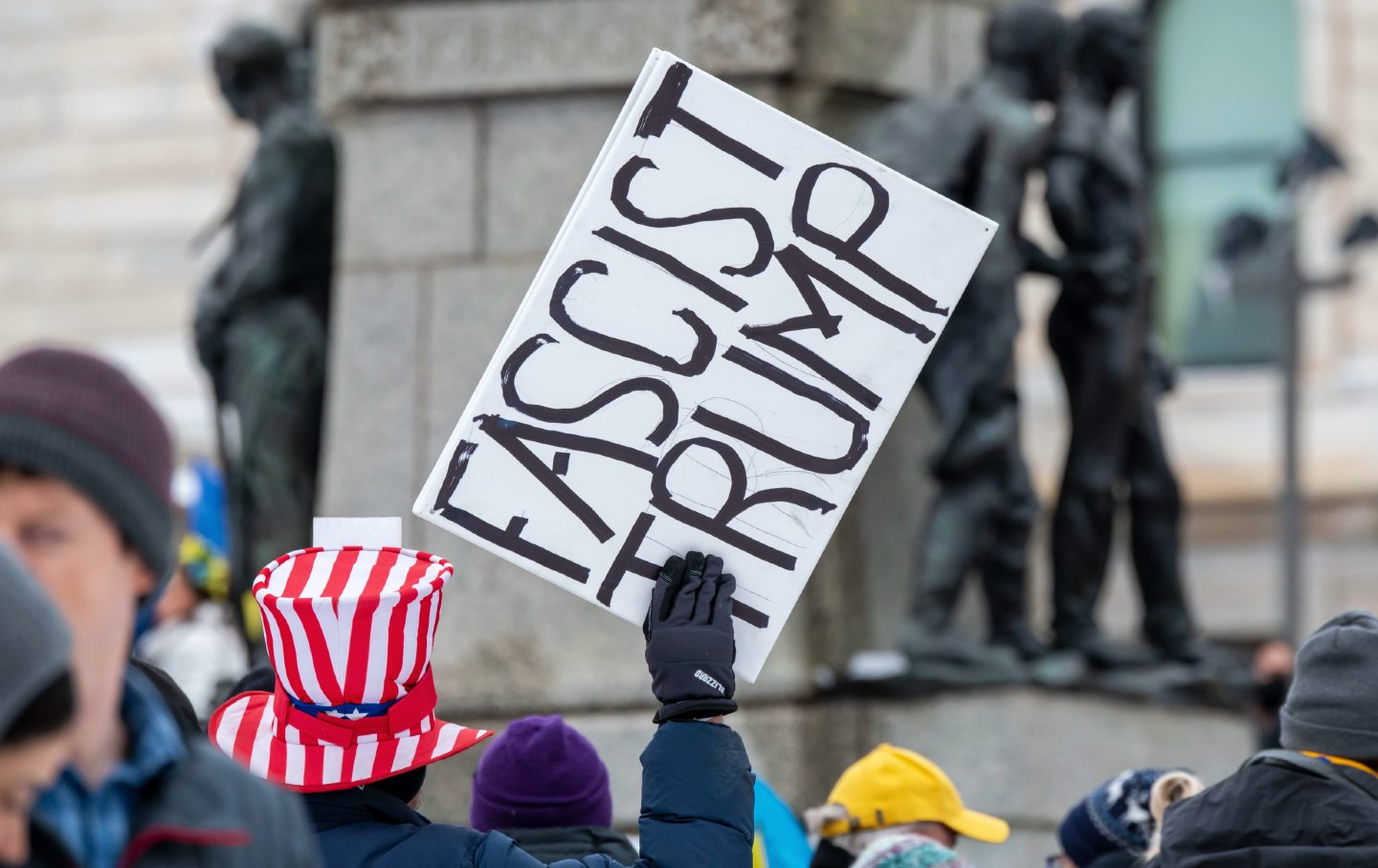

Is Donald Trump a fascist? The debate itself is revealing.

(Michael Siluk / UCG / Universal Images Group via Getty Images)Since the beginning of Donald Trump’s presidential campaign in 2015, there has been a public obsession with whether fascism—that hideous ideology of Hitler and Mussolini—has been reborn in the United States. But debates about fascism in the United States are nearly a century old. Ever since Sinclair Lewis published his dystopian novel It Can’t Happen Here in 1935, the question of whether fascism could happen here has been posed.

Even so, there is something different about the fascism debate today. Beyond the superficial labeling of an opponent, it has generated deep analytical work involving multiple schools of thought (including the Black radical tradition, Marxism, the Frankfurt School, Cold War liberalism, to name a few) and addressed profound concerns (such as race, gender, technology, and the environment). There is no obvious or stable political axis (progressive/centrist, left/center/right) to the debate. And the debate has not been confined to academia. Along with interventions from scholars addressing a popular audience, it has extended into mainstream public discourse, with pundits and politicians alike weighing in.

As the fascism debate enters into its second phase—triggered by Biden’s slide in general election polls and growing anxieties that Donald Trump could actually win—it is worth figuring out how the dispute arose in the first place. On one hand, such an inquiry might conclude that the debate has been little more than “an exasperating and self-involved intellectual sideshow,” as The Nation’s Chris Lehmann put it in November of last year. On the other hand, given all the spilt ink, exploring the debate might disclose something fundamental about the Western mindset, culture, and political values by revealing our ultimate—and sometimes conflicting—concerns and how we choose to portray them.

In the 15 years prior to Trump’s election in 2016, accusations of fascism often came from the right and were directed at liberals. In 2009, for instance, Fox News compared newly elected president Barack Obama to Mussolini. Tea Partier claims that Obama was a fascist were common. It is worth noting that despite the long shadow cast by 9/11, the political establishment rarely labeled George W. Bush or his policies as fascistic—in fact, many liberals who defended Bush’s war on terror came close to sharing his view that democracy stood embattled by the threat of “Islamofascism.” Some of those defending this line would later see fascism in Trump.

During Obama’s presidency, establishment Democrats expressed little fear of American democracy being threatened by domestic fascism. After all, despite growing right-wing populist sentiment, Obama had won, the two preceding elections against white Republican presidential opponents with relative ease; and despite Trump’s nomination as the Republican candidate, most polling and election forecasting indicated that Hillary Clinton would easily win the next. Shocking as it is now, some liberals were encouraged by Trump’s nomination, claiming it would provide Clinton with the easiest path to the White House. Trump, Jonathan Chait wrote in February 2016, “would almost certainly lose.”

But Trump’s election ushered in a radical volte-face: Terrified by the results, many Democrats, as well as some Republicans, suddenly began affirming that democracy was in crisis. A plethora of books intended for mass consumption soon appeared—some written mere days after Trump’s victory—offering prophecies of democracy’s imminent demise.

Trump’s victory emotionally and intellectually deregulated a democratic establishment that eight years earlier had expressed overwhelming joy over something long thought impossible: the election of the first Black president. How could Trump, someone so obscenely opposed to cherished political norms, ascend to the nation’s highest office? What was happening to the country?

For many, Trump’s election called into question a core political assumption—perhaps an unconscious one—that had long been in place since the end of the Cold War: the notion that there is no viable political alternative to liberal capitalist democracy. The fracturing of this confidence led many Americans to conclude that their democracy was actually fragile—vulnerable to injury, even death. But who is to blame for this, they demanded?

For some, the problem had little to do with any inherent shortcomings of the country’s democratic norms and institutions. Rather, the crisis was the work of sinister forces seeking to undermine democracy at home and oppose it abroad. “The bad guys are winning,” proclaimed the centrist Anne Applebaum in The Atlantic: Illiberal actors were becoming the norm, a historical reversal of the political direction of the 20th century, which ended in liberalism’s Cold War triumph. But how to label these enemies of democracy?

Critics, of course, had been arguing for decades that economic globalization brought about ever more extreme economic inequality, both within the United States and internationally, and especially between Northern countries and the Global South. This, they argued, was bound to cause a global populist reaction. The 2008 financial crisis and the European sovereign debt crisis amplified the problem, as critics warned that the political center had become too technocratic, too closed off from democratic processes—that is, too cut off from the people. To many, the populist backlash in the United States and Europe hardly proved surprising. Was it such a shock that dissidents from across the political spectrum expressed disdain for the status quo?

But not everyone agreed. Indeed, much, if not all, of the recent fascism debate that exploded after Trump’s victory served as a proxy debate for a larger discussion of what constituted a thriving democracy. To what degree are threats external to the mainstream to blame for the crisis of democracy, and to what extent could the fault be laid at the feet of the internal democratic shortcomings of the political system itself?

Viewed in this manner, it might be tempting to see the fascism debate as the continuation of the political dispute between those who in the 2016 Democratic presidential primary supported the liberal Hillary Clinton and those who preferred the socialist candidate Bernie Sanders. Accordingly, those who invoke charges of fascism against Trump are viewed by their critics on the left as part of the political establishment that has dominated the Democratic Party for decades and whose hegemony is being challenged on both the left and the right. In this reading, the leftists who resist applying the fascism label to Trumpism are the true democrats who see in fascism talk a rhetorical ploy that distracts from what is truly ailing American society: growing socioeconomic inequality brought on by the neoliberal policies that the Democratic Party has embraced for decades.

The limitation of this view, however, is that it telescopes the fascism debate into a narrow political perspective that does not do justice to the diverse perspectives and concerns of those who engage in it. It also doesn’t map onto key figures of the fascism debate. Democratic Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, along with plenty of Marxist thinkers critical of liberalism, for instance, believes that the United States has a real problem with fascism. Viewed in this light, the fascism debate is a Rorschach test for understanding what is ailing American society.

During a time of crisis, when the world is made strange, there is an urge to turn to the past to understand the confusion of the present—to find meaning in history. Who and/or what we blame for causing the crisis will often influence the historical comparisons we choose to make. The presentist component is unavoidable as we project our values and anxieties onto past periods. The historical analogies that intellectuals and scholars have picked to understand what happened with Trump’s election, or with the January 6, 2021, attack on the Capitol, are neither random nor self-evident.

In his best-selling On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century, the historian Timothy Snyder predicted that Trump would undermine American democracy just as Hitler had undermined liberal institutions in Germany: by cultivating obsequious civil servants and businessmen who followed his orders and by deceiving the naïve masses by manipulating the truth. Despite criticism from his fellow historians for making simplistic and reckless comparisons, Snyder doubled down on his use of fascism analogies by predicting that it was “pretty much inevitable” that Trump would try to stage a Reichstag fire to overthrow democracy. Snyder believes that January 6 vindicated his claims. Whether one agrees with him or not, Snyder’s interventions blur the line between history and prophecy. And the Trumpist right has responded by hurling accusations of fascism back at their accusers, as the writings of Dinesh D’Souza demonstrate par excellence.

Perhaps the primary complaint of drawing on the darkest moment of Europe’s history to explain Trump is summed up by the historian Samuel Moyn: It abnormalizes a presidency that is quintessentially a product of the American system and therefore fails to examine “the status quo ante Trump that produced him.” But is it even necessary to make recourse to Europe to explain American fascism?

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →The historian Robert Paxton claims “that the earliest phenomenon that can be functionally related to fascism is American: the Ku Klux Klan.” One scholar who has put forth a powerful defense of this position is the American cultural historian Sarah Churchwell. Many of her arguments rely on the observations of Black political leaders of the 1930s, such as W.E.B. Du Bois, who explicitly interpreted Jim Crow America in a fascist light.

African American thinkers, and often those associated with the Black radical tradition, have long used the term “fascism” to describe numerous features of American politics and society. A classic example of this is Angela Davis’s 1971 essay, “Political Prisoners, Prisons, and Black Liberation,” which views the disproportionate rate of Black incarceration in the United States through as having parallels with fascism.

Watching from afar, however, intellectuals from the Global South often view the fascism debate as just another instance of American provincialism. As Faisal Devji explains, “seeing what is happening in the United States and elsewhere today as the struggle of fascism against liberalism or white against Black conceals more than it reveals, because it is a view that refuses to look beyond America or the West in a historical context which has become global.” There is something contradictory and misguided, observes Devji, in thinking about the world in purely EuroAmerican terms.

As this brief tableau suggests, historians dominate today’s fascism debate. This might explain why so much of the debate is wedded to the horrors of the past. Little wonder that historians prophesied that the 2022 midterms would see the GOP win majorities in the House and Senate, allowing Trumpist forces to legally undermine democracy, just as Hitler had undermined the Weimar Republic (a failed prophecy); that Ron DeSantis stands to achieve this victory as a smarter, better educated, and more fascistic version of Trump (another failed prophecy); that Trump, like the Undertaker, will rise again and this time achieve his fascist designs; that if Ukraine doesn’t completely defeat Russia the entire “free world,” is in jeopardy; that something must be done to stop China lest the liberal international order enter hospice care.

Anyone concerned about democracy must take seriously those forces that are hostile to it, and the divide within the Democratic Party over the Israel-Gaza conflict could usher Trump back into the White House. Still we should be suspicious of historians moonlighting as prophets of doom and democratic avengers. Their desire to sound the tocsin against the threat of recurrent heresy too often obfuscates, rather than clarifies, the complexity of current events. Being overfixated on the traumas of history can make it difficult to grasp what is new. “The past may live inside the present,” observes the historian Matt Karp, “but it does not govern our growth.” Instead of letting fears distort politics, as another fascism debate is most likely bound to do, the goal now should be to push forward with the hope of building a better society for a new age.

More from Daniel Steinmetz-Jenkins

How Did the Democrats Get Here? How Did the Democrats Get Here?

Talking with Tim Shenk about party realignment, the legacy of 1990s political consultants, the 2024 election, and his new book, Left Adrift: What Happened to Liberal Politics.

Aziz Rana Wants Us to Stop Worshipping the Constitution Aziz Rana Wants Us to Stop Worshipping the Constitution

A conversation with the legal scholar on why its unusual the Constitution is core to American national identity and his new book The Constitutional Bind.

Talking “Solidarity” With Astra Taylor and Leah Hunt-Hendrix Talking “Solidarity” With Astra Taylor and Leah Hunt-Hendrix

A conversation with the activists and writers about their wide-ranging history of the politics of the common good and togetherness.

The Problematic Past, Present, and Future of Inequality Studies The Problematic Past, Present, and Future of Inequality Studies

Branko Milanović’s century-spanning intellectual history of inequality in economic theory reveals the ideological reasons behind the field’s resurgence in the last few decades.

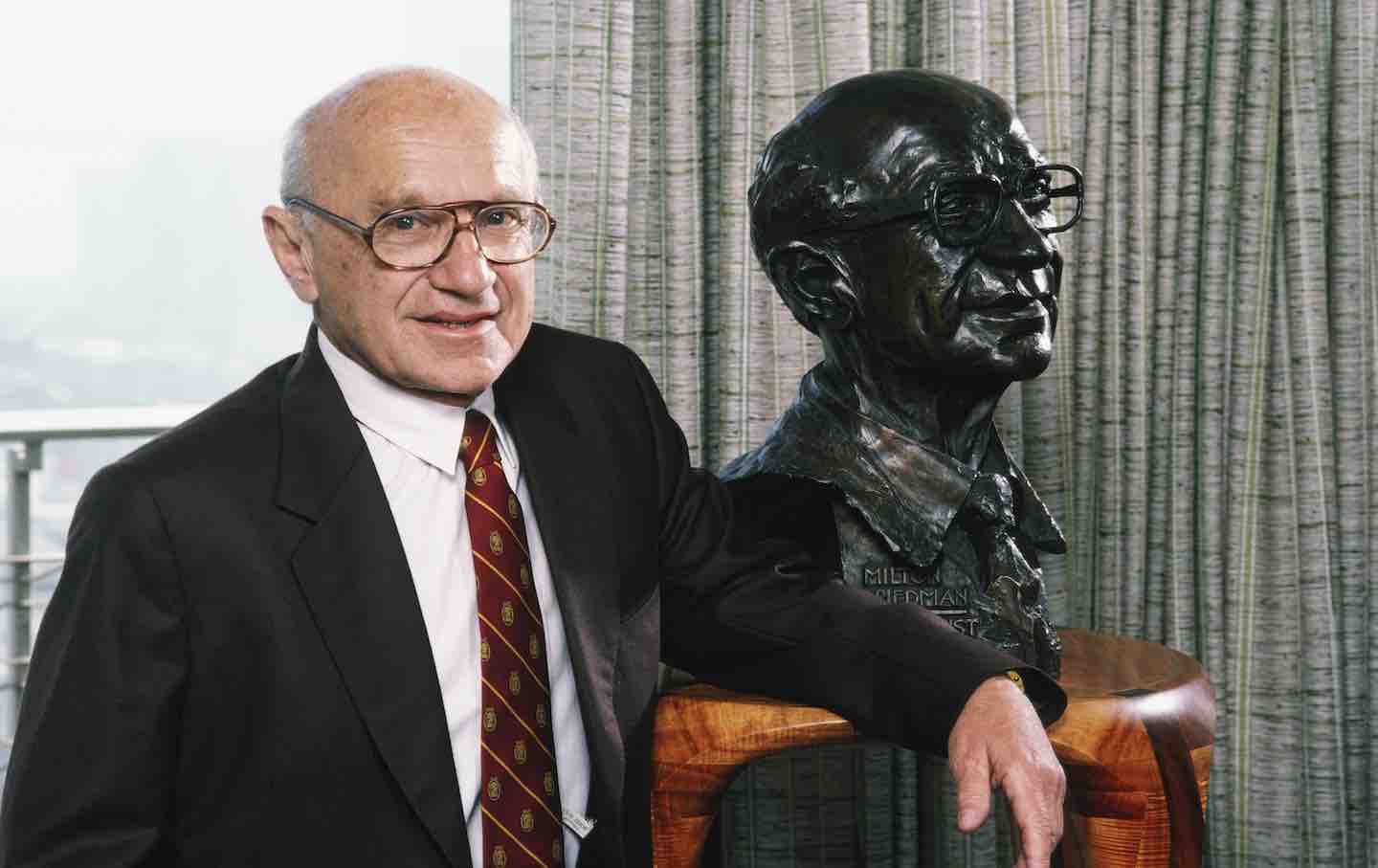

The Century of Milton Friedman The Century of Milton Friedman

An interview with Jennifer Burns on her authoritative new biography of the American economist and the personal and intellectual origins of his theories.

Wendy Brown: A Conversation on Our “Nihilistic” Age Wendy Brown: A Conversation on Our “Nihilistic” Age

The Nation spoke with the political theorist about the multifront crisis of the post-Trump era and the moral and intellectual commitments of scholars and higher education.