Aziz Rana Wants Us to Stop Worshipping the Constitution

A conversation with the legal scholar on why its unusual the Constitution is core to American national identity and his new book The Constitutional Bind.

Why do so many Americans worship the US Constitution? In his new book, The Constitutional Bind: How Americans Came to Idolize a Document That Fails Them, Aziz Rana argues that today’s reverence for the Constitution—among both Democrats and Republicans—is a distinctive product of the 20th century and the Cold War. A culture of reverence around the Constitution grew, Rana observes, as the United States—seeking global dominance—offered it as an anti-imperial paradigm for all those foreign states emerging from colonial rule. The US Constitution thus became the lodestar for proper governance globally. Hence why the United States has felt little reluctance in intervening in states abroad, but is hesitant to overhaul its own Constitution, as it represents, for Americans, what is timelessly true and right for all. The result, as Rana puts it, is a “constitutional bind,” which prevents a much-needed overhaul of the Constitution to reflect new and pressing political and socioeconomic realities. The Nation spoke with Rana to discuss the origins of today’s worship of the Constitution, earlier periods in US history that were much more open to significant constitutional reforms, and how the constitutional bind can be broken today.

—Daniel Steinmetz-Jenkins

DSJ: There’s an interesting moment early in your book where you try to explain the ambivalence that marks contemporary liberal views of the Constitution. Some, you say, are clearly aware of the antidemocratic features of the Constitution, be it the Electoral College, or the fact that the Senate “gives more power to voters in Wyoming than California,” or federal judges who serve for life, and so on. At the same time, you observe that many liberals today see the Constitution as the “salvation” of the Democratic Party, especially in the age of Trump. What explains this tension?

AR: I see this tension as tied to the role the Constitution plays in the US, which is critically different from the role that written constitutions play in many countries. Outside the US, constitutions are often rules for governing, which may or may not remain effective. When these legal-political orders break down or social upheaval brings new elites and alliances to power, old documents can be jettisoned and new ones written. Societies typically do not treat their written constitutions as being at the core of their national identity.

But in the United States, the 1787 Constitution has become wrapped up with a very specific account of what it means to be American. In particular, the Constitution is often treated as the concrete mechanism for fulfilling what Swedish sociologist Gunnar Myrdal called the “American Creed,” the idea of the US as being committed from the founding to principles of liberal equality. For some liberals, at a moment when this vision feels like it is under attack from resurgent white nationalism, holding on to the Constitution can feel especially culturally essential.

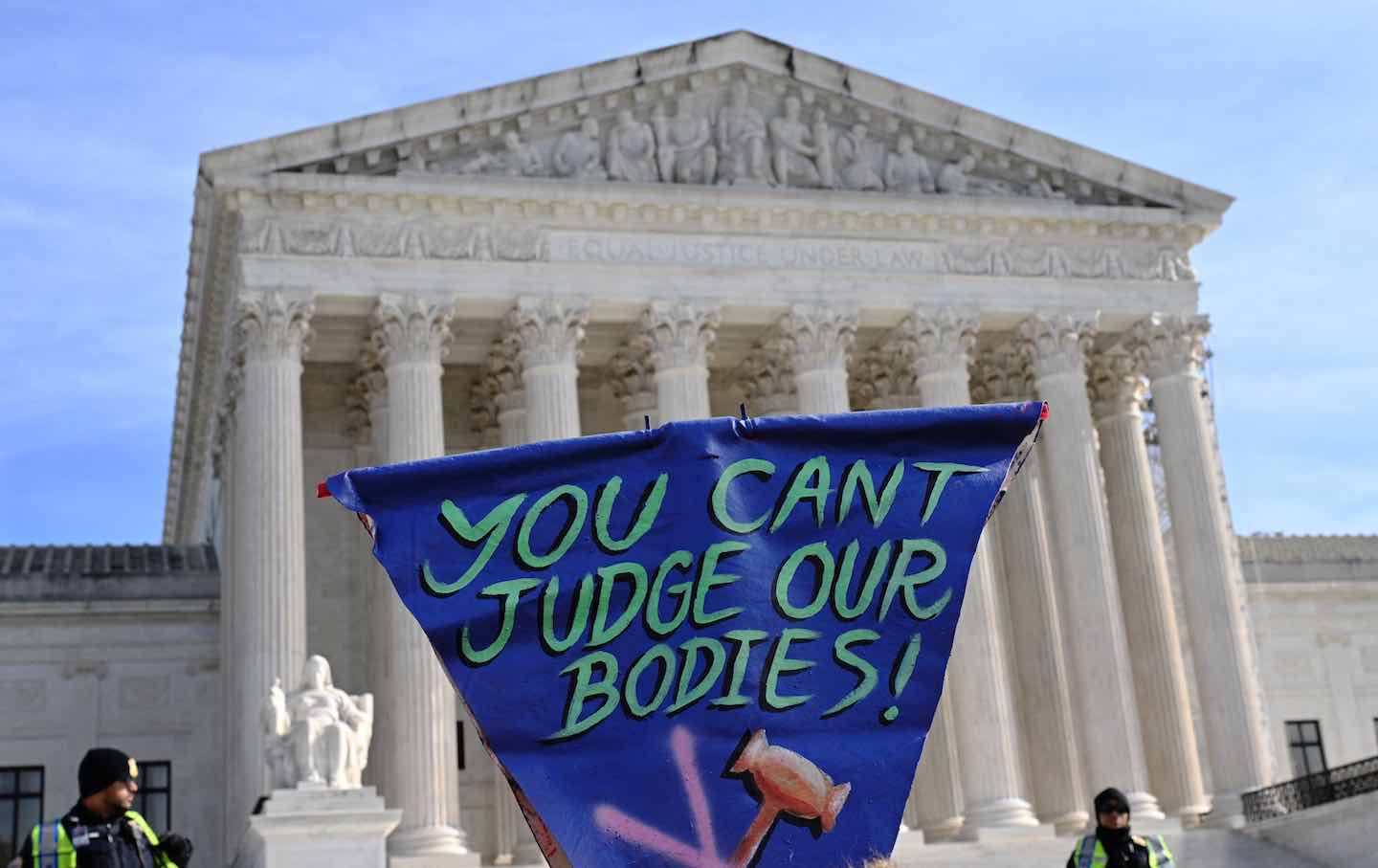

The problem, of course, is that the divided liberal mind—which details constitutional flaws even as it depicts the text as “salvation” from Trump and Trumpism—is effectively an invitation to reaffirm the very arrangements that have facilitated, both today and in the past, the authoritarian brand of politics that liberals condemn. Moreover, such an approach fundamentally misunderstands the challenge of the present. The country today is wracked by a series of unfolding crises—intense police and military violence at home and abroad, financial crisis, extreme class inequalities, the carceral state’s generational effects on poor and minority communities, white authoritarianism, and ecological disaster, to name a few. Our political class has seemed paralyzed in the face of these crises, and our constitutional system has only intensified them.

Nonetheless, there is this nostalgic wish in some centrist and liberal quarters that if everyone speaks of the country through the language of creed and Constitution, as typified by Barack Obama’s civic appeals, then the US will somehow be placed back on a frictionless Cold War liberal path. But one piece of Obama’s legacy is the demonstration that even the most charismatic version of that faith in creed and Constitution was not enough—and may, in truth, have buttressed an exhausted and limited political approach to the economy, race, and foreign policy.

Today, the only pathway out of these enveloping crises entails actually and concretely addressing the underlying problems themselves rather than hoping to restitch a national fabric through stock stories of the founding and redemptive purpose. And this will likely require fundamentally reconstructing the constitutional project.

DSJ: How does this tension relate to perhaps the book’s key idea, namely what you call “creedal constitutionalism”?

AR: When Americans in the 20th century venerated the wisdom of the Constitution, they increasingly embraced a very particular account of national meaning, which finally consolidated in official form during the Cold War. Creed and Constitution were tied to additional ideological pillars, all of which would have been highly contested in earlier periods of American history. These pillars included an anti-totalitarian account of individual liberty and market capitalism; an embrace of American checks and balances, with the Supreme Court at the forefront; and a commitment to US global leadership and primacy. On the face of it, all of these were disparate ends, which need not go together and might well be in profound tension. But the narrative that American politicians and commentators developed around the Constitution fused these ends into a single, pervasive American ideology.

They provided the official story about why the Constitution promoted a just political, economic, and social order, and why its principles should be replicated everywhere. In this way, the Constitution became the normative core of what magazine magnate Henry Luce famously dubbed the “American Century.” And so, when Obama stands in Philadelphia before a picture of James Madison with the words, in large type, “Writing the Constitution”—as he did during his 2020 Democratic National Convention speech—it is this interrelated set of commitments that he invokes as the bulwark against Trumpism.

The reality today is that this official Cold War version of the American project is breaking down before our eyes. From the debates over how the Constitution protects Trump’s impunity and feeds right-wing authoritarianism to the reverberating implications of Gaza, we are all witness to the basic failures everywhere of the American “rules-based” order. And just as both the American constitutional model and American international power were joined together, their entangled limitations now simultaneously lay exposed.

DSJ: In the book you also discuss various 20th-century movements that were opposed to the Constitution. Which did you focus on, and why?

AR: Alongside the account of how creedal constitutionalism became dominant, the book narrates another vital story. It details how the dominant constitutional culture erased from shared memory and popular debate the rich and once-vibrant assortment of constitutional ideas embraced across left movements. Especially before the strictures of Cold War orthodoxy, activists and critics articulated genuine constitutional alternatives to the existing state and economy, aimed at creating—for the first time in the United States—an authentically democratic society.

The book thus offers an alternative archive of reformers, rarely engaged with in legal scholarship or mainstream conversation, but whom I argue should be understood as important constitutional thinkers in their own right: Eugene Debs, Crystal Eastman, Laura Cornelius Kellogg, W.E.B. Du Bois, Vito Marcantonio, Jawaharlal Nehru, Oginga Odinga, Grace Lee Boggs and James Boggs, Beulah Sanders, Afeni Shakur, and Hank Adams, among numerous others.

I also interrogate their concrete reform suggestions, especially strategic questions—of great relevance for today—regarding normative vision and political viability. For instance, early 20th-century socialists called for basic transformations to the existing political order—by breaking up the system of state-based representation; eliminating the Senate and Electoral College; moving toward proportional representation across government; reforming the bench; and simplifying the amendment process.

And throughout the 20th century, anti-colonial voices specifically sought to link these alterations to the political system with comparable ones to the social order. Those changes would have ended the colonial status of existing territories; shared real sovereignty with Native nations; provided broad-ranging reparations, at home but also for communities abroad that had faced security-state intervention; expanded socioeconomic rights and wealth transfers (such as through the public and universal provision of food, housing, child care, medical care, reproductive rights, a nonexploitative job, and a guaranteed income); demobilized and reimagined the military, security, and policing frameworks; decriminalized the border; and provided legal and political avenues for the remedy of both historic colonial crimes and ongoing state violence.

Taken as a whole, this competing archive ranges across social movements and even transnational identities, embodying perspectives grounded in Black, Indigenous, feminist, labor, immigrant, and Third World politics. Indeed, some figures were not Americans at all, but due to US state power they had no choice but to grapple with the terms of the American constitutional model. All of these voices confronted the constraining structures of their times with novel and evolving constitutional diagnoses and strategies. Given the well-worn nature of our current constitutional discourse, their collective reflections offer fresh insights, especially about the ties binding constitutional design to capitalist market relations, structural hierarchies, and imperial power.

DSJ: You seem to suggest that there are many historical variants of “creedal constitutionalism,” but that imperialism proves to be their main trigger. Can you elaborate on this?

AR: A mixing of creed and Constitution first emerged out of antislavery politics and even became formally instantiated in the text through the Reconstruction-era amendments. Yet by the end of the 19th century, Reconstruction had collapsed and these ideas were marginalized within white society. They only returned with renewed life in the context of American overseas expansionism—particularly the unexpected and brutal Philippine independence fight. Moreover, the additional elements of an augmented creedal constitutional framework gained resonance through further global episodes: World War I, World War II, and the Cold War confrontation with the Soviet Union.

Why was this the case? I don’t think you can account for key shifts in the meaning of the US Constitution without centering the rise of the United States from a regional hegemon to the world’s preeminent global power. The 20th century witnessed two devastating world wars and the breakdown of the great European empires. As Asian and African independence gained force by the mid–20th century, this sustained anti-colonial struggle permanently transformed international and domestic discussions about inclusion and exclusion. Forced to contend with these changes, European states came to deemphasize racial hegemony and ethno-racial solidarity as the explicit bases of national greatness and ongoing international engagement.

In this way, the US was no different. For a country whose leaders sought preeminence in a decolonizing and largely non-European world, conceiving of America as a “white man’s country”—to use Teddy Roosevelt’s evocative phrase from the first decade of the 20th century—became a nonstarter. US officials needed to explain, to themselves and others, how the US actually represented a departure from the racial hegemony that marked the age of European empire.

Furthermore, they aimed to explain why the United States should enjoy an essentially imperial right on the global stage—namely, the right to exercise tutelage over foreign, especially non-white, polities, and thus to assert an international police power to reconstruct those societies in keeping with domestic interests. Against this backdrop, US policymakers and commentators—soul-searching on behalf of the country, but also responding to these external realities—steadily embraced creedal constitutionalism as the core story of American peoplehood.

DSJ: How does this work itself out during the global Cold War? During this time, of course, the US was trying to woo and coerce the countries of the Global South onto its side. Did this lead to creedal constitutionalism in those nations that aligned with the US?

AR: During decolonization, constitution-writing emerged as a key symbolic and institutional mechanism for independence-era national elites. For domestic audiences, the documents codified both political rupture with the old empire and the principles of the new polity. On the international stage, they allowed nationalist leaders to assert equal sovereign statehood.

In a world in which the challenges and needs of new polities moved to the forefront of global discussions, American elites embraced creedal constitutionalism in part because it allowed them to position the US as the original constitutional, anti-imperial paradigm—the first among equals, both substantively and temporarily, since the US Constitution had been around for well over a century by that point. Constitutionalism provided both an ideological basis for international arrangements under American supervision and the model for how foreign states should themselves be domestically structured.

And there is no doubt this American fusing of American primacy with creedal constitutionalism had real resonance globally, including in the non-European world. Such resonance was further bolstered by racial reform successes at home, embodied by decisions like Brown v. Board of Education and the steady undoing of legalized segregation.

Part of this success was also due to the fact that American political elites did not approach their use of creedal constitutionalism purely instrumentally, reaching for venerative arguments simply as a veil to justify assertions of power. Policymakers and commentators came to believe, deeply and authentically, in both a specific vision of US constitutionalism and the necessity of the American Century. This profound emotional investment is a large part of what made the culture that eventually emerged around the Constitution one of romance.

DSJ: In what way was this an American imperial project rather than a form of anti-imperialism, which is often suggested?

AR: Most writing about American constitutional culture treats it as a check on empire. But conceptually, this ignores how the construction and maintenance of American international police power—in service of market dictates and related state-security objectives—became invested with moral legitimacy precisely through a constitutional register.

Creedal constitutionalism, therefore, was not antithetical to global dominance. Instead, reverence for the Constitution stood as the ethical core of the modern American imperial imagination. In other words, US global primacy was ideologically grounded in what amounted to a form of imperial constitutionalism. In particular, constitutional veneration operated on both sides of the ledger with respect to legal rule-following: It created the terms for inclusion and rights protection, and it could in key moments push back against specific abuses. But it also buttressed an overarching account of American power and purpose, which legitimated coercive practices in the first place.

Indeed, from the Philippines after 1898 to Vietnam, Indonesia, and Latin America during the Cold War to Israel/Palestine today, US officials have time and again justified even extreme mass violence against civilians as still in line with their bedrock constitutionalism. And when this narrative has proved implausible, officials typically treat constitutional violations as unfortunate necessities or mere aberrations. Or, especially when violence is perpetrated by repressive non-white allies, it is presented as the fault of those societies—implicitly or explicitly due to ethno-cultural limitations in the Global South.

DSJ: Might the story you tell, in which nationalism is essential to creedal constitutionalism, provide an alternative historical explanation for the origins of contemporary right-wing populist movements, both in the US and abroad?

AR: One feature of resurgent white nationalism in the US is the language today of racial reaction. Some Trumpist defenders of racial hierarchy may make explicit claims about racial superiority. But more commonly, aligned politicians and commentators will attack “CRT” or “multiculturalism,” or promote educational repression and harsh crackdowns on immigrant rights, by claiming to stand for both the universalistic principles of 1776 and the Constitution. For liberal and left Americans, raised with the civil rights invocation of creed and Constitution, all of this can feel like a cynical smokescreen or a jumble of incoherent ideas.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Yet what the imperial story highlights is that a reason why creedal constitutionalism spread across the white American public was always twofold: It was both a real language for ameliorative reforms on issues of race, but—especially through experiments in places like the Philippines—it could still be powerfully melded with arguments about Euro-American cultural exceptionalism. The specialness of Euro-American society, the fact that the United States was the place where universal principles were truly developed, gave it a right to supervise less “mature” societies. There is a reason why white supremacists like Woodrow Wilson became champions of spreading a version of creed and Constitution to the globe. Indeed, by the American mid–20th century, I would argue that the dominant language of racial reaction—especially but not exclusively in the North and the West—mobilized ideas of American universalism and exceptionalism precisely as a way of preserving racial hierarchies.

Today, everything from conservative school bills to Supreme Court invocations of “colorblindness” are effectively the most potent discourses of racial reaction. This speaks to the flexibility of creedal constitutionalism, both as a language of reform and of hierarchy, as well as its complicated entanglement with American ethno-nationalism. There is a persistent desire to treat creed and Constitution as part of the good, liberal nationalist tradition in the US, rather than part of the bad “illiberal” and ethno-nationalist variety. But in truth, it is very hard to separate the two. And the cultural power of white nationalism in the United States today is rooted in the capacity of the right to tap into the very same ideological formations that solidified during the Cold War.

DSJ: We are in a constitutional bind of our own making, as your book illustrates, so what might be the way out of it?

AR: A key related piece of the 20th-century constitutional story is that the document increasingly became owned, culturally and politically, by a small coterie of legal experts and judges. But the judges, and the law professors they primarily listened to, were never unbiased actors; they were overwhelmingly institutional players who drank deeply from the well of US exceptionalism. Our political culture has more or less handed the reins of constitutional authorship, memory, and knowledge to these voices, all to the exclusion of nearly everyone else. Today, however, at a time of rolling national crises and thorough institutional dysfunction, Americans should not grant them near-total reform authority or virtually exclusive power to define what counts as constitutional.

Thus, the first constitutional need is to reclaim mass-movement and popular ownership over constitutional politics—including basic reflection about what a reform project might even aspire to. And, critically, moving in this direction means linking constitutional debate (a debate that is often seemingly technical and remote) to the material and moral concerns—over race, economy, and war—that reverberate in American life. This linkage is key, if for no other reason than that the current rules of the constitutional game place a massive thumb on the scale when it comes to what issues are debated and what policy outcomes result. Simply put, many of the material and moral changes Americans may want depend on alterations to the democratic infrastructure of the country.

Thus, one entry point for confronting the constitutional bind may be to engage with matters that are not even directly about the legal and political process, although those are certainly critical too. This would concern expanding the power of left constituencies, especially cross-racial and working-class groups. Such an approach speaks to the importance for activists now to strengthen the intermediate and meaning-making institutions that house left mobilizations. Increased movement power and stronger intermediate institutions, like energized unions, are both the necessary requirement for change and the actual safeguard against state, business, and racial repression. And just as with past left voices, activists today should also imagine a variety of levers to the electoral system or to the workplace—democratic improvements at the polls or at the job—that, if enacted, would dramatically heighten the bargaining power and social position of working people. These levers are all best understood as pragmatic reforms with revolutionary implications: small-scale shifts that can alter how contests with corporate employers proceed or what types of legislation are possible to enact.

At the same time, the convulsive politics at home around Gaza highlight that one cannot imagine a domestic democracy agenda as ultimately succeeding while ignoring the nature of American power elsewhere. Just as the Constitution should not be treated as a domain for apolitical legal experts, the long history of the ties between American constitutionalism and American power underscore that substantial constitutional reform cannot be separated from what is typically framed as foreign policy. What happens abroad shapes the potential for meaningful change at home, and vice versa. This necessitates an expansive vision for the country, one capable of constitutionally reconstructing both the domestic and global face of American governance.

DSJ: When you state that the Constitution “must be removed from its national pedestal,” what role would it then come to play in your eyes?

AR: Removing the 1787 Constitution from its “national pedestal” means confronting seriously its profound flaws. It also means pushing back against an American constitutional imagination that treats constitutions as deified higher laws, calcified in time, supervised by elite lawyers, and insulated from popular negotiation and renegotiation.

But if I do not believe that Americans should approach this or any constitutional text with such idolatry, that does not mean that the existing legal infrastructure and constitutional system should be ignored. Instead, they have to be engaged with strategically—including with the aim in mind of building mass-movement power.

Under our present conditions, the courts remain an extraordinarily powerful site for the application of state authority. And the design of legal-political institutions produces deeply distorting effects on our politics, fundamentally constraining the capacity of transformative majorities to pursue liberating change. All of this suggests that even if one wants to create a fundamentally different social order, it is vital that movements and activists have a constitutional politics.

They need an account of when and how to use the courts, even if only to hold those in power to the rules they themselves have accepted or to provide the communities most marginalized with a reprieve from everyday violence. Movements also need an account of which institutional reforms to the constitutional landscape—and through which legal-political pathways (say amendment or legislation)—can actually have those revolutionary implications or help to improvise a new social order out of the old.

Thus, above all, I see removing the Constitution from its “national pedestal” as going hand in hand with a dramatic expansion of American democratic imagination. It is a vital precondition for creating a cultural and political world in which Americans can build and rebuild their institutions in service of equal and effective freedom for all.