Enough Is Enough: No More Polls!

They distort our democracy, have little value, and make us all insane. We should do what other countries do, and ban them this close to an election.

ENOUGH.

(NBC News)For all the election-season lamentations over AI mischief, deep fakes, and dis- and misinformation, there’s a central source of toxic data derangement hiding in plain sight: the erratically useful, wildly misleading, and ideologically disfigured polling industry.

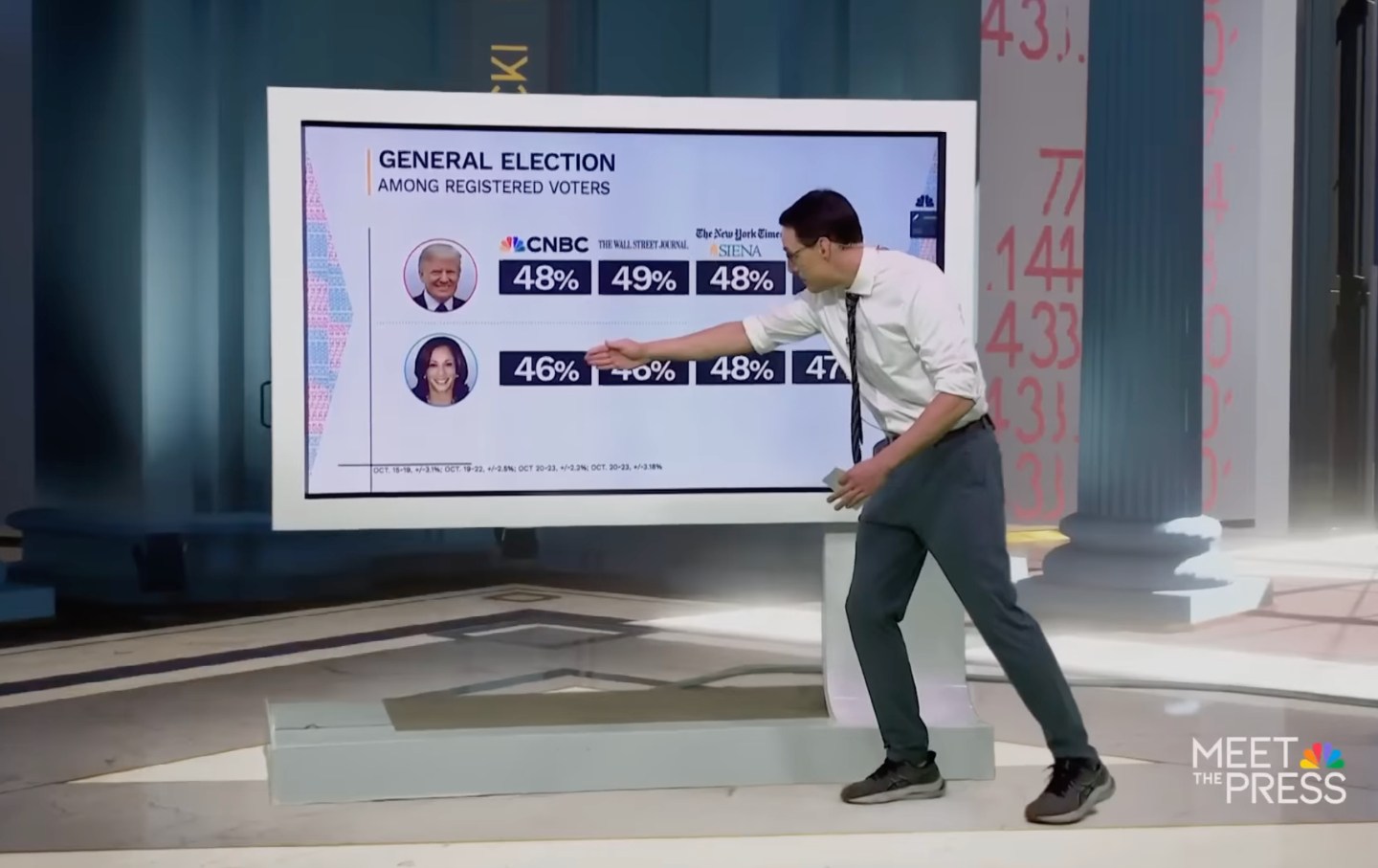

The ways that hotly touted polling findings distort and disfigure our basic understanding of what’s going on are teeth-gnashingly familiar by now. Just over the past month, we’ve had news that the Rasmussen Group, the long-standing right-leaning polling operation, has been sharing advance findings with the Trump campaign. We’ve seen aggregation guru Nate Silver locked in a fierce, and hilarious, set-to with academic election forecaster Allan Lichtman. We’ve seen grim, if wildly inconsistent, data on the state of the election from the prestigious New York Times/Siena survey and a host of other polls clustered around a more-or-less evenly divided portrait of the electorate. We’ve seen the same Paper of Record publish, in the same edition, forecasts from Silver and Democratic consultant James Carville predicting polar opposite election outcomes.

The same refrain that applies to the guiding narratives of the general election, in other words, applies to the rolling, manic effort to document the core dynamics of the contest in real time: What are we even doing here, people? What’s the real benefit to the public of this numbers-driven fog of political warfare?

In our own age of counter-majoritarian, blinkered negative polarization, polling increasingly functions to reinforce the narratives campaigns put forward about surging popular support and finely crafted appeals to undecided swing-state voters. As the Rasmussen episode shows, some pollsters even appear to be distorting their own research. A host of other right-leaning polling operations set out in 2022 to flood polling models with dubious surveys purporting to show a red wave in process; undeterred by that failure, they’re again trying to shift perceptions toward a Trump win this cycle—a brand of impression management that could go a long way toward fomenting another MAGA coup attempt in the event of a Trump loss. Meanwhile, the keepers of aggregate models are increasingly prone to the same mischief; the Real Clear Politics site has long driven its models, and its aggregated politics coverage, rightward. Nate Silver is now advising an elections-handicapping crypto site partially funded by a Peter Thiel investment firm; like brain-dead horse-race correspondents at national politics desks, he has a clear incentive to produce the appearance of a tightly fought election in order to gin up business.

With the alleged scientific and impartial effort to track public opinion and prospective voting behavior honeycombed with these kinds of perverse incentives, it’s long past time to ask what polling is really for. As a set of empirical assumptions about past patterns of voting behavior, it isn’t much use as a forecasting tool, as the last several election cycles have shown—and that’s especially the case in a moment like ours, when many of the basic assumptions and ideological precepts that have long governed politics are up for grabs.

As an internal device allowing campaigns to allocate resources and broker new coalitions, polls appear to deliver suspect intelligence at best—as the well-flogged tale of the 2016 Clinton campaign’s neglect of Michigan and Wisconsin makes plain. Finally, as a guide to voting behavior, polling imparts very little useful information. Surveys of undecided voters are little more than glorified guesswork, as are the efforts to plot out the actions of “likely voters”—a category of diminishing utility as younger, low-propensity, and first-time voters exert greater influence than the mythic figure of the purse-lipped undecided voter. Polling has served some useful purposes in highlighting changing voter concerns, but largely in ex post facto focus groups. Again, as a form of prophecy or divination—which is what polling becomes in standard horse-race coverage—it seems not much better than a coin toss.

So here’s a modest proposal: Let’s block poll findings out of the final stage of our presidential elections. In the hectic last lunge toward Election Day, the defects of polling become greatly magnified, as voters are prone to use the alleged shifts in the mass electorate’s mood as rationales for casting ballots in a fog of empirically dubious pseudo-pragmatism—or else to refrain from voting at all. Particularly when media outlets breathlessly report poll results without any close attention to margins of error or crosstab findings that can greatly reshape, or even invalidate, top-line results, the potential mischief wrought by our flailing polling discourse is far greater than whatever notional benefit comes from obsessive poll reporting.

There’s also a little-noted vice grounded in our poll-saturated political discourse:The omnipresent din of poll reporting encourages ordinary voters to think and act like pundits—that is, to weigh their own actual principled beliefs and policy preferences against a debased vision of how to leverage their votes toward or against the prevailing patterns of belief and conduct in the American electorate.

It should always be remembered, first of all, that pundits are complete dipshits. But beyond that, the emergence of a pundit-style electorate is in many ways how we’ve wound up in the dismal pass that’s hollowed out the civic arms of our major parties and empowered the burn-it-all-down balloting reflex that’s arguably the chief characteristic of the GOP’s MAGA base. If we’re able to rein at least part of the impulse now goading voters into second-guessing the value of their ballot as anything other than an instrument of culture-war vengeance, that alone is ample reason to stifle the poll noise during the final three weeks of a presidential campaign.

The idea of a prolonged poll silence isn’t as outlandish as it might seem at first glance. It is, after all, common practice in many democracies to institute a similar silence of political advertising in the final days of their elections—and in America’s decadent, hypercapitalist political discourse, polling is rapidly devolving into a form of pseudoscientific campaign advertising.

Most European Union countries ban publicly sharing polling information for a period close to an election, ranging from 24 hours to a full two weeks before Election Day; so do countries like South Korea and Taiwan. The ideal-type model of deliberating democratic citizens holds that they collect and harvest information to prevail upon their consciences to grasp the best choice at the ballot box. Polling gives voters none of that—it merely traffics in a hall-of-mirrors account of likely political behavior derived from the likely political behavior of others. Even if the data at the basis of this Baudrillardan exercise were always airtight, it still serves no intelligible democratic purpose.

One of the only positive structural developments of the 2024 election cycle was the inadvertent discovery that a greatly truncated campaign season—produced by Joe Biden’s withdrawal from the race in July—is a civic boon. Voters have been able to inform themselves on a far saner timeline, and the corrosive effects of dishonest campaign advertising, misleading social media alarms, and rancid push polling have all been diminished as a result. So let’s build on this one encouraging precedent: Embargo all polling from early October onward, and de-punditize the electorate.