A Cooler Future Means a World With Less Pavement

Amid climate-fueled heat waves and floods, cities around the country are rethinking the streetscape.

Traffic on a Los Angeles freeway during the evening rush-hour commute on April 12, 2023.

(Frederic J. Brown / GettyThis article originally appeared in Nexus Media News.

It all started because a man named Arif Khan wanted a garden. In 2007, he had recently moved into a house in Portland, Ore., whose backyard was covered in asphalt. Some friends helped him tear up the impervious surface, and soon after, they won a small grant to carry out a similar project in front of a local café.

“It was a one-off,” said Ted Labbe, cofounder of Depave, an urban greening movement. “But it was so successful that the next year we got solicited to do three projects, and then five the year after that. It just kept escalating.” In the 15 years since breaking ground on Khan’s backyard, Depave has completed 75 projects in schoolyards, churches, and other community spaces across Portland.

The Depave movement has spread across the United States and Canada in recent years as climate-related extreme heat and flooding have made some cities rethink the wisdom of all that heat-absorbing, impervious surface area.

Depave’s newest chapter is in Chicago, where about half of the population lives in areas where temperatures are at least eight degrees higher than the city’s base temperature, a disparity that can prove deadly in heat waves. More than 60 percent of the city is covered in impervious surfaces, and when record rains fell in early July, more than 12,000 residents reported flooding in their basements.

“Environmental justice communities are suffering from a lot of pavement-related issues,” said Mary Pat McGuire, a professor of architecture at the University of Illinois, and the founder of Depave Chicago. “We’re trying to bring attention to it so that the city will start treating this as a critical part of climate adaptation and social justice.”

Since launching in 2022, McGuire and a group of volunteers have been holding listening sessions across the city to identify local needs. She and her cohort recently finished drawing up plans for their pilot project: greening a public schoolyard in West Englewood, a low-income neighborhood in southwest Chicago.

“They teach the Montessori method, which is very hands-on,” McGuire said. Depave consulted with sixth, seventh, and eighth graders, along with teachers, parents, and school board members to draw up a blueprint for the new schoolyard. It includes pollinator gardens, an outdoor classroom, log structures, bioswales, and shady trees. “Green infrastructure isn’t clean, neat and tidy,” McGuire said. “We’re going to get messy.”

Paved roads and parking lots take up about 30 percent of urban areas in the United States. (In some cities, like New York, that figure is closer to 61 percent.) Parking lots alone cover more than 5 percent of developed land in the lower 48 states, according to the US Geological Survey.

“We’ve had a love affair with paving things for several generations,” said Brendan Shane, climate director at the nonprofit Trust for Public Land. “We have too many unnatural paved surfaces and not enough natural surfaces, and that’s creating these urban heat islands [and] rapidly flooding neighborhoods.”

Extreme heat and flooding are particularly acute in low-income communities of color, which typically have less green space than wealthy, white neighborhoods, a legacy of redlining practices.

Replacing asphalt with greenery has benefits beyond lowering temperatures and reducing flood risk. It’s also associated with lower stress levels, a reduction in noise, fewer traffic-related injuries, and even restoration of local biodiversity. It can also improve air quality: Asphalt releases hazardous air pollutants into communities, especially in extreme heat and direct sunlight.

“We want to bring it to the city’s attention that this is a critical part of climate adaptation and solving social inequity,” McGuire said.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Amid climate-fueled heat waves and floods, cities around the country are rethinking the streetscape. In Phoenix, Ariz., where asphalt can get so hot during heat waves it can give third-degree burns, officials are painting surfaces with reflective grey paint. Nashville, Tenn., which experienced deadly floods back in 2010, has transformed alleyways into blooming, bee-filled rain gardens.

More than a decade ago, Chicago invested $14 million in building what it dubbed the “greenest street in America.” The two-mile stretch of Blue Island Avenue and Cermak Road in the Pilsen neighborhood sports rain gardens, permeable pavements, and solar-powered street lights.

“There are a lot of great strategies and plans out there,” says Vincent Lee, a principal at Arup, an engineering and architecture firm. Last year, Arup released a study examining the “sponginess”—or ability to absorb rainfall—of several cities and making the case for cities to invest in nature-based solutions to prevent flooding. “But implementation is a major challenge due to lack of funding, outdated policies and codes and minimal cross-sector collaboration.”

Many advocates say schoolyards are ideal sites for greening projects because they represent an opportunity to educate students about climate resilience. Space to Grow, another Chicago organization, has overhauled 34 schoolyards over the last decade, replacing asphalt with permeable sports fields, rain gardens, and other porous surfaces.

“Our schools are the center of the community, and we want to make sure kids are excited to be in those spaces,” said Meg Kelly, Space to Grow’s director.

According to the organization’s data, replacing asphalt with permeable sport fields, rain gardens, and other porous surfaces has reduced ground temperatures by up to 54 degrees Fahrenheit and captured more than 3.5 million gallons of stormwater, alleviating neighborhood flooding.

McGuire said she wants Depave Chicago to help neighbors avoid the next flood or find respite from the next heat wave, but she also wants to help Chicagoans envision a different future for their city.

“It’s about changing attitudes towards concrete,” she said. “We’ve been missing an opportunity to embrace nature in the city, and I’m just trying to get people to look at the world around them and dream of something different.”

More from The Nation

This Solar Panel Kills Fascists This Solar Panel Kills Fascists

New York’s Build Public Renewables Act will reduce carbon in the atmosphere, combat inequality, and help workers. It might also defeat Trumpism.

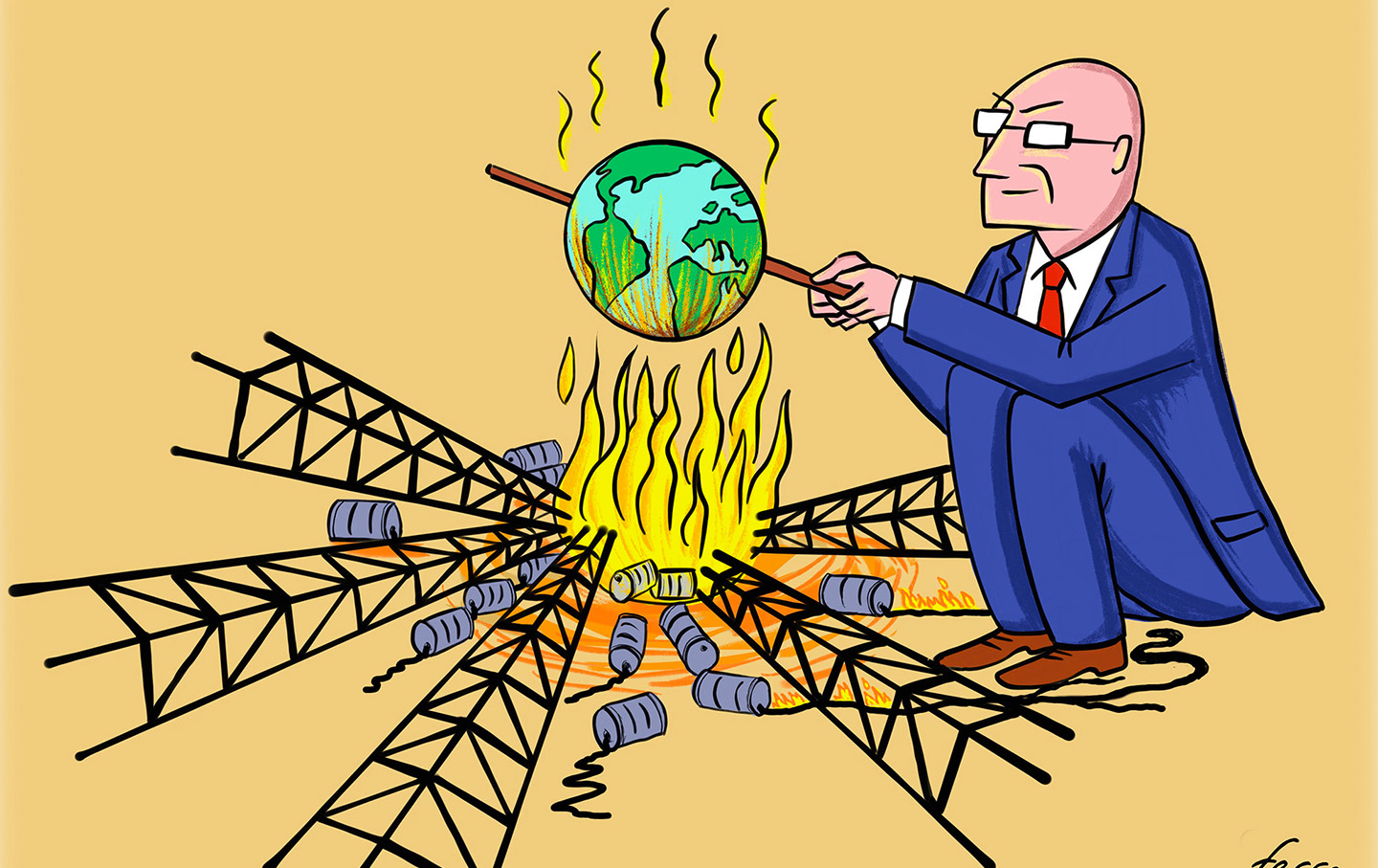

Global Burning Global Burning

The oil industry denies climate change, opposes regulations, and significantly contributes to the environmental crisis.

The “Worst COP” Concludes With a “Heartbreaking” Climate-Finance Deal The “Worst COP” Concludes With a “Heartbreaking” Climate-Finance Deal

Activists say the climate agreement effectively signed away the 1.5-degree Celsius target—”our only real chance to safeguard humanity’s future.”

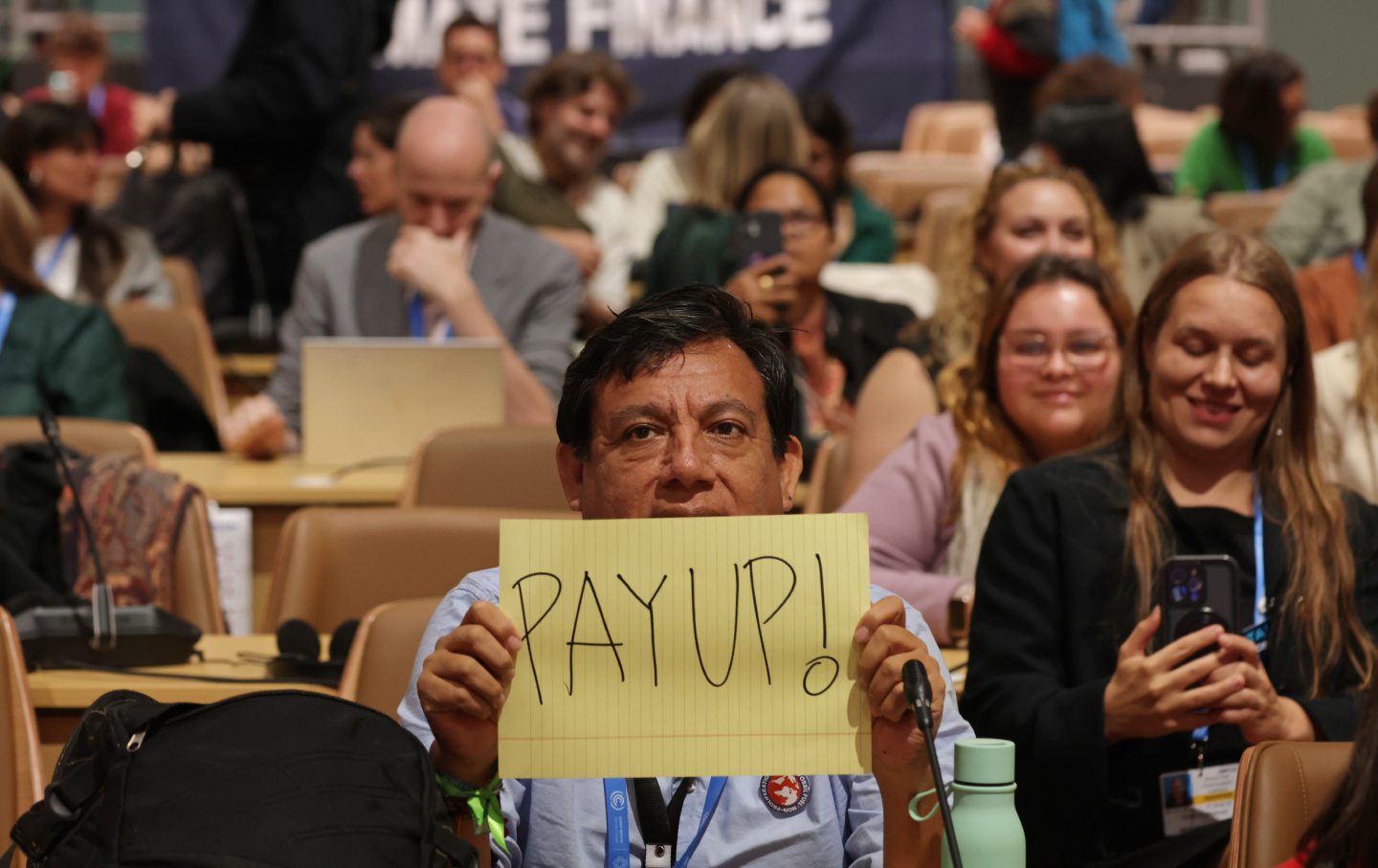

Rich Countries Must Pay Up or Humanity Will Pay the Price Rich Countries Must Pay Up or Humanity Will Pay the Price

The climate activist Lidy Nacpil says the climate bill owed to developing nations is in the “trillions, not billions.”

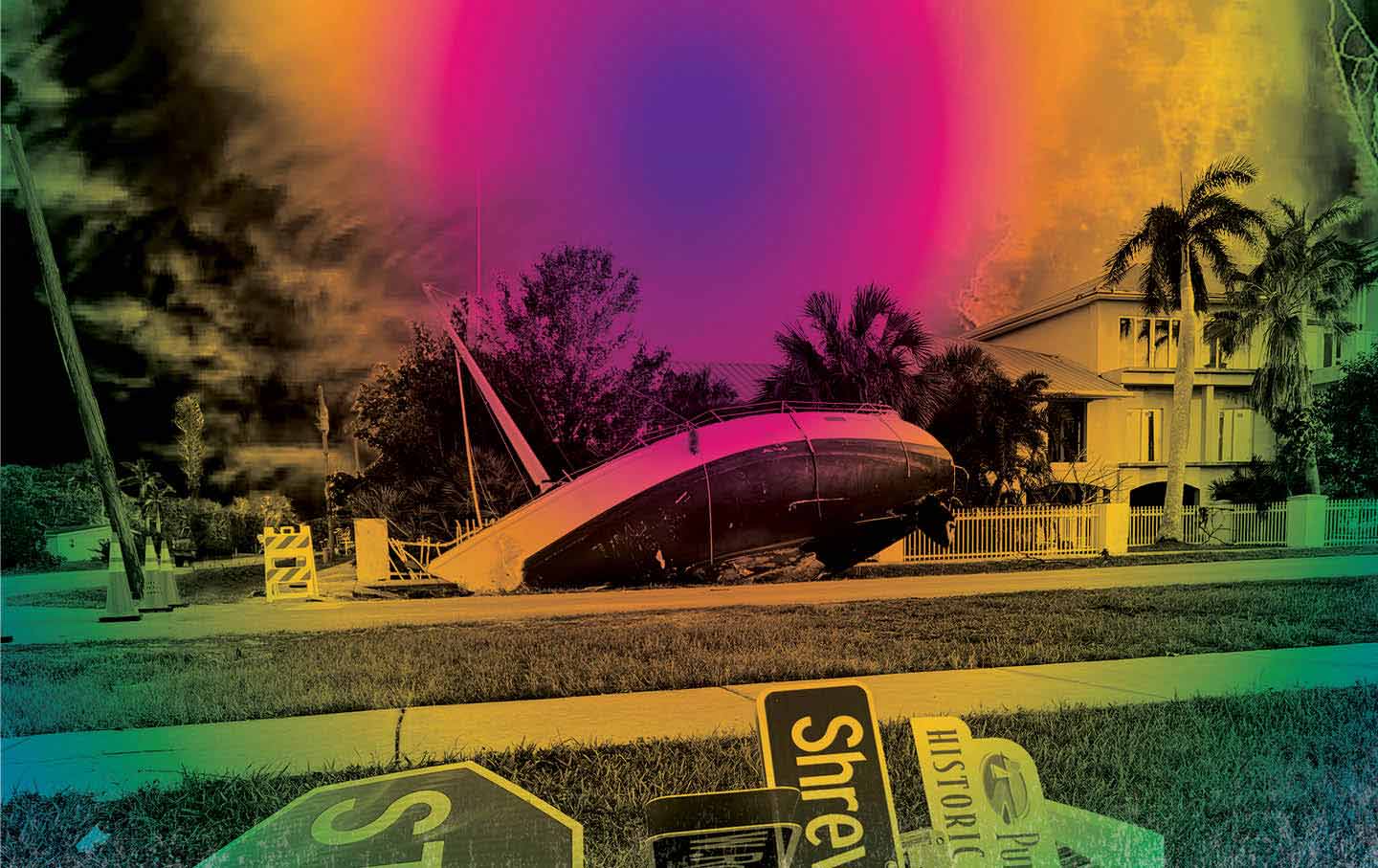

Climate Change Is the Real National Security Threat Climate Change Is the Real National Security Threat

In the wake of Hurricanes Helene and Milton, it’s clear we’re defending against the wrong perils.

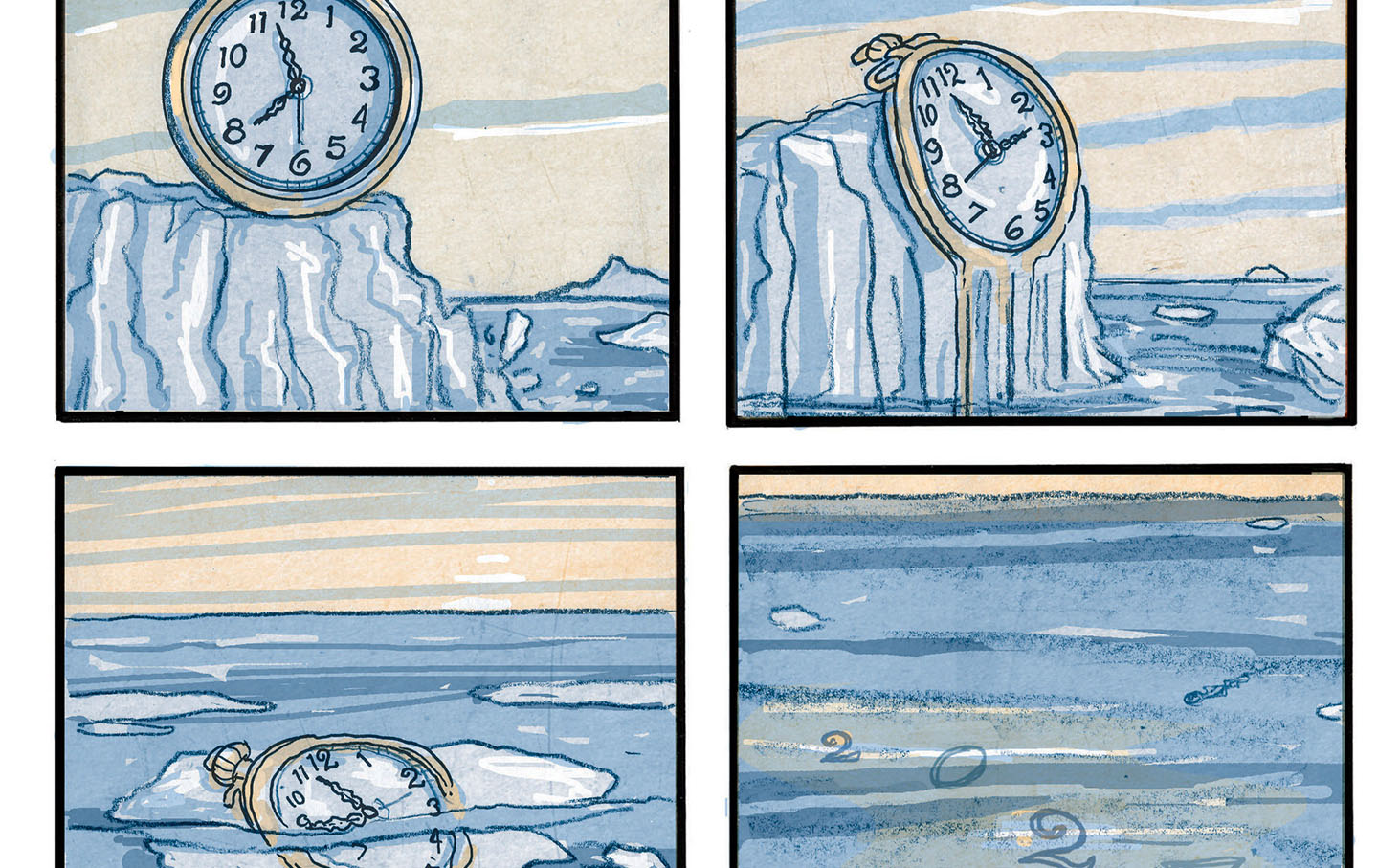

Acting on Climate Change? Acting on Climate Change?

The opportunity is melting away.