Raising the Minimum Wage Comes Cheap

Studies overwhelmingly show that the effect of increasing the minimum wage on employment rates is basically zero.

California fast food workers now have one of the highest minimum wages in the country. In 2022, the state Legislature passed the FAST Recovery Act, which established a fast food council made up of workers and corporate representatives that would set standards for wages, hours, and working conditions. A year later, after a well-funded attack on the law at the ballot box, Governor Gavin Newsom signed legislation enacting a $20 minimum wage for fast food workers, which took effect in April, and set the council up to develop further recommendations for raising pay.

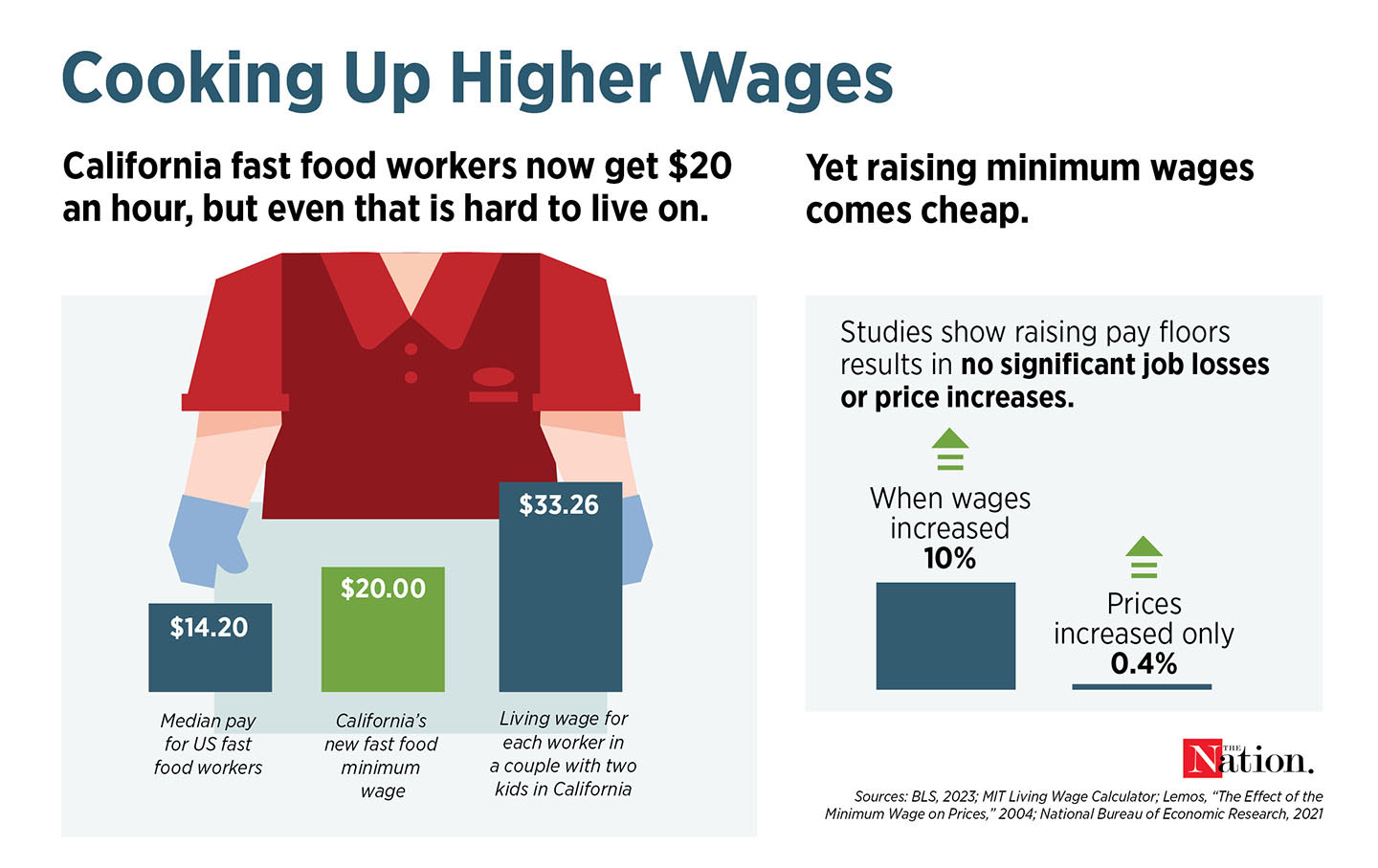

The new wage is a hefty increase; the state’s minimum wage for all workers is $16 an hour, and in 2022, the average wage for California’s fast food workers was $16.21. Nationally, median pay for fast food workers is just $14.20 an hour. But consider that a $20 wage still amounts to just a bit over $40,000 a year—and that’s if someone works full-time for 52 weeks a year. In California, nearly 40 percent of fast food employees work less than 35 hours a week, even though half the workforce wants more hours. Researchers at MIT estimate that a living wage in California is $27.32 an hour for a childless single person; someone in a family with another working adult and two children needs to earn at least $33.26 an hour.

In anticipation of the higher-wage mandate, fast food chains have claimed that they’ll be forced to fire workers, and some people have already lost their jobs. But studies overwhelmingly indicate that, in the end, California’s fast food workers will be better off.

Companies tend to handle a higher minimum wage not by laying people off but by raising prices. A number of chains, from McDonald’s to Chipotle, have already warned that they may start to charge more, although it’s unclear whether the $20 wage is to blame, since they were already hiking prices in California at a faster clip than anywhere else in the country. Still, McDonald’s has responded to past minimum-wage increases not by bringing in robots to replace workers but by raising the price of a Big Mac. It’s not likely to be an astronomical change: One review of studies found that increasing wages by 10 percent raised prices by, at most, 0.4 percent.

Some restaurants may be forced to close. But according to a March 2024 study, the ones that disappear are more or less the ones that can’t hack it—the least productive small companies. That lines up with another study finding that the lower-rated restaurants are the ones that exit. The successful ones, meanwhile, end up more profitable.

Employment can be affected, but it’s not typically through mass layoffs. The same March study found that companies react to a higher minimum wage by slowing down hiring and holding on to their existing workers. Even in “highly exposed industries,” such as the restaurant sector, companies “do not substantially reduce employment,” the authors found. Both young people and low-wage workers are likely to stay employed and make more money.

That finding lines up with many, many others. A study that looked at 138 minimum-wage increases between 1979 and 2016 found that the impact on jobs was “mostly close to zero and not statistically significant,” but that pay increased not just for those making the new minimum wage but for those earning slightly more, too. A different study of 172 minimum-wage increases from 1979 to 2019 similarly found “little evidence” of jobs lost despite “a very clear” increase in overall pay. The same for a study that compared counties that raised their minimum wage to neighboring counties that didn’t over a period of 16 years. One study from 1994 that looked specifically at the impact of higher minimum wages on the fast food industry found no evidence of reduced employment and actually found that the number of jobs increased, as did a different study in 2023.

A 2009 survey of 64 studies found the same thing: Across all of the findings, the average impact on employment was close to zero.

California’s $20 fast food wage floor is new, but what ends up happening there could hold national significance. Legislators in New York and Massachusetts have considered raising their states’ minimum wages for all workers at least that high. Lawmakers who want to meet the growing call for a $20 wage can rest assured that, more likely than not, the workers meant to be helped by it will hold on to their jobs and reap higher pay.