A Memoir for the Post-Truth Era

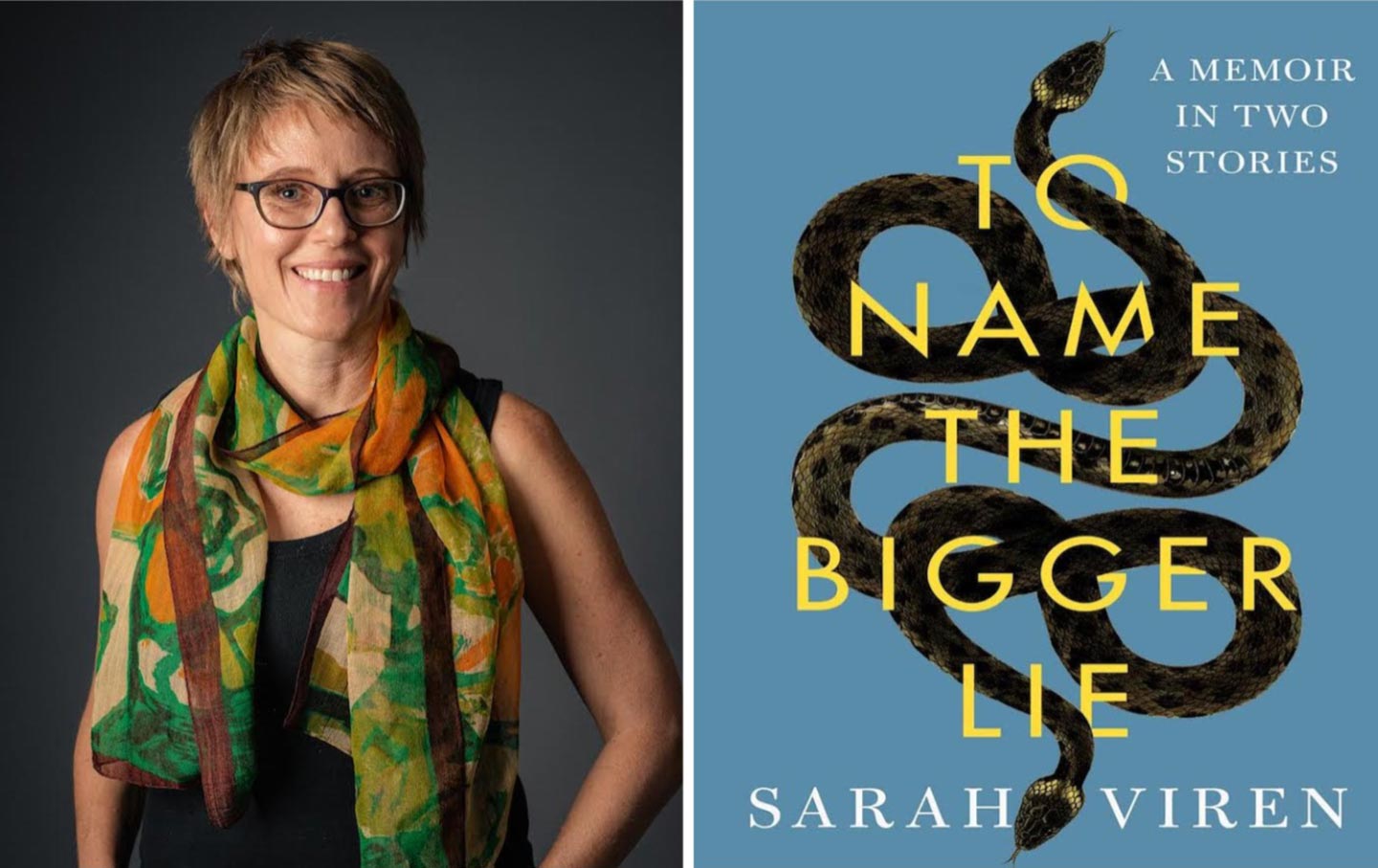

In Sarah Viren’s To Name a Bigger Lie, she investigates how conspiracy theories have changed her relationship to the world.

When Sarah Viren was 15, she spent a good deal of time, like many teenagers, staving off boredom during her classes in school. There was one exception: Dr. Whiles’s class on “Inquiry Skills.” Viren’s memoir, To Name the Bigger Lie, begins in an air-conditioned classroom in Tampa, Fla,. after Dr. Whiles has flung a pencil across the room. “Did it hit the wall?” he asks. Obviously, Viren thinks. But by now she knows the evident, obvious answer will never be correct in this classroom. Dr. Whiles is different from her other teachers: Ruminative and intense, he’s known to lambaste television (the “drug of the masses”) and complain that students are “manifesting adolescent behavior.” As Dr. Whiles moves through his curriculum—a capacious selection of Plato, Aldous Huxley, and Douglas Adams —Viren follows along keenly. She takes careful notes, vigilantly “recording each clue in the larger mystery Dr. Whiles seemed to be unspooling that year.”

Books in review

To Name the Bigger Lie: A Memoir in Two Stories

Buy this bookBut when Dr. Whiles teaches the same students two years later, his lessons are less of a “mystery”—instead, it seems he’s looking for converts. He screens The Christian History of America, lectures on the New World Order, and has the class watch a debate in which a clean-cut man in a tailored suit calls the “Holocaust story” an “irresponsible exaggeration.” It becomes increasingly difficult to parse what’s true and what’s not, in part because Dr. Whiles conflates factual instances of clandestine government abuse (such as the CIA’s MK-ULTRA experiments) with unverifiable conspiracy theories. The many instances of actual government malfeasance make the unsubstantiated ones seem somewhat believable. So after Dr. Whiles plays half of a Holocaust debate (the denying side), Viren bursts into tears. “I had believed the man at that podium, at least briefly,” she admits.

Set between 1993 and the present, To Name the Bigger Lie at first reads like an incisive, if familiar, investigation into the conspiratorial thinking that flowered on combative, theatrical, partisan platforms like Fox, on algorithm-driven social media, and, eventually, in the White House. But the memoir quickly shifts from a sociological inquiry into something more subtle. Viren, who teaches creative writing at Arizona State University, uses a narrative collage to capture the emotional texture of a certain place and time. She layers episodes from Dr. Whiles’s class with other high school memories, like the crush she develops for her best friend. As Viren recalls that mystifying, instant intimacy—beautifully described as “slipping on a clean dress or moving furniture to just the right spot in a room”—she brings us back to a period of young adulthood riddled by confusion. Viren recreates that swampy atmosphere on the page, making room for both doubt and discovery. The result is something rich and confounding: an investigation of uncertainty, that unsettling sensation we tend to shrink from before we can make sense of it.

In 2019, when Viren was writing this memoir, something happened in her life that derailed her work altogether: Her wife, Marta, was accused of sexual assault. It started with an anonymous Reddit post accusing Marta of throwing a party for her graduate students, plying them with alcohol, and inviting them up to her bedroom. Shortly after the posts, Arizona State University opened a Title IX investigation, calling in Viren and Marta for extensive interviews. As Viren recounts these months in To Name the Bigger Lie, expanding on an essay published in The New York Times Magazine in 2020, she carefully skirts a thicket of questions repeatedly posed in cases of sexual harassment and assault. First, she dismisses the possibility that Marta might be guilty: “I tried to picture her asking for sexual favors,” Viren writes. “But I couldn’t suspend my disbelief.” Instead, Viren fixates on a single question: Who was behind the accusations? Was it a former student, or “someone misogynistic who had been put off by [Marta’s] bluntness,” or “one of her exes, someone who’d been holding a grudge”?

In her quest to find an answer, Viren admits that she started to sound a lot like a conspiracy theorist. Much like Dr. Whiles, she was “tracing the connections of an elaborate scheme, one that made sense only if you were willing to believe that one person—or a cabal of people—had the power to manipulate the fate of ordinary lives.” Only, in this case, the malevolent presence was real: An eccentric and obsessive acquaintance named Jay, competing against Viren for a coveted job offer at the University of Michigan, had framed Marta. This section proceeds like a detective story, with a suspect, a quest to uncover evidence, and a ticking clock.

But once again, Viren manages to complicate the story by letting in a sliver of doubt—not about Marta’s innocence, but about the act of writing. The authors of nonfiction, Viren argues, “know that we will never produce writing that is an exact replica of our original text, which is to say reality.” One way to manage that inevitable discomfort is to “replicate reality on the page in a way that makes the reader forget the impossibility of our task.” This, we understand, is what Viren set out to do in the section on Dr. Whiles: She’s absorbed us in a story so urgent and vivid that we don’t consider what’s been left out.

But there is an alternative. Just as a translator might make “decisions that don’t feel fluid or natural in the target language but that represent something essential carried over from the original,” a memoirist might reveal her own awkward and imperfect choices. In the third section of her book, Viren discloses the editorial decisions that shaped the story she eventually published in the Times Magazine. We learn that she originally planned to conclude the piece on a punitive note, gently encouraging readers to identify Jay: “Our lawsuit is public record. You can search for it now.” But after an editor’s intervention and some distance, Viren landed on a more generous ending: “Now, the story belongs to you.”

It’s a slight shift that changes the tone of the essay from vengeful to reparative. And by asking us to imagine an alternative version of that article, Viren reminds us that contemporary circumstances inform the construction of the past. She also suggests that writing can be used for various ends: to accuse or to condone, to satisfy or to unnerve, to solve mysteries or to pose them. It’s to Viren’s credit that she doesn’t conclude with the neat categories of good versus evil, but asks her readers to consider the shifting nature of truth.

One problem in attempting to tie these two stories together is that they offer somewhat conflicting lessons on how to identify a lie. One advises that when attempting to separate false information from the truth, we defer to the principle of Occam’s Razor: The best explanation is usually the simplest. The other suggests that when events don’t align with our intuition, perhaps some secret, sinister force is operating behind the scenes.

So when Viren tries to find a unifying thread in the final two sections of the book, it can feel contrived. She poses a series of questions that include “Can words cause harm?,” “Can ideas be dangerous?,” and “Is…cognitive dissonance…good for us?” In search of the answers, she imagines conversations with Plato, Jay, and the giant, affable tortoise that lives in her backyard. She quotes Hannah Arendt, Virginia Woolf, and Arthur Schopenhauer. She contacts Dr. Whiles to ask if he believed in the feverish lessons he shared with his class—or if, as he claims, he was only trying to provoke critical thinking. (In an e-mail exchange, Dr. Whiles argues that his course encouraged questions like “How do we know?”) She includes several creative and somewhat harebrained digressions—like a scene in which she imagines Marta, Jay, and herself as characters in Sartre’s No Exit. But the more Viren searches for a single idea that fuses the two stories together, the clearer their contradictions become.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Back in high school, after Dr. Whiles converted to Christianity and started peddling conspiracy theories to his students, he gave a lecture on T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land. Viren adored the poem’s sense of “creeping dread,” its haunting lyricism. But under Dr. Whiles’s interpretation, these electric lines—“April is the cruelest month, breeding / Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing / Memory and desire”—are reduced to a simple solution. According to Dr. Whiles, The Waste Land is about the resurrection of Christ: “At the end of the poem, Jesus reappears, and then rain comes and there is hope again.” Listening to her teacher’s explanation, a dull appeal to Eliot’s own religiosity, Viren is stung by disappointment. “What I loved in that poem,” she recalls, “was not finding the answer buried within its lines, but experiencing the mystery within the layers of meaning.” It’s not only that she doubts the veracity of Dr. Whiles’s analysis, but that, by reducing a grand and puzzling poem to an explicable and narrow message, he has extinguished the work’s magic.

Viren’s interest in uncertainty is an antidote to this type of thinking. She attempts to tell stories, as she writes, “in ways that open up meaning, that elicit questions rather than tendering answers.” And if her two stories build toward a concluding point, it’s the importance of keeping ourselves open to both wonder and doubt. Instead of grasping for certainty, Viren suggests that we parse messy questions with mulish patience, accepting both what’s demonstrably true and what remains unknowable. After all, it turns out that Dr. Whiles’s explanations don’t make the world appear newly visible but rather cramped and false. In place of a world run by a secret and all-powerful cabal, Viren describes one infinitely more immense, bewildering, and alive.

More from The Nation

The Agony of Aaron Rodgers The Agony of Aaron Rodgers

Is he the world’s most interesting athlete or is he just a washed-up crackpot?

Can You Understand Ireland Through One Family’s Terrible Secret? Can You Understand Ireland Through One Family’s Terrible Secret?

In Missing Persons, Clair Wills's intimate story of institutionalized Irish women and children, shows how a family's history and a nation’s history run in parallel.

Peter Schjeldahl’s Pleasure Principle Peter Schjeldahl’s Pleasure Principle

His art criticism fixated on the narcissism of the entire enterprise. But over six decades, his work proved that a critic could be an artist too.

How the Western Literary Canon Made the World Worse How the Western Literary Canon Made the World Worse

A talk with Dionne Brand about her recent book, Salvage, which looks at how the classic texts of Anglo-American fiction helped abet the crimes of capitalism, colonialism, and more...

Along the Roads That Built Modern Brazil Along the Roads That Built Modern Brazil

José Henrique Bortoluci's What Is Mine tells the story of his country’s laborers, like his father, who built its infrastructure, and in turn its fractious politics.

The Long History of the "Elsewhere Museum" The Long History of the "Elsewhere Museum"

Can the ethnographic museum be reinvented?