The Irrepressible Elaine May

Her films reveled in the possibility of capturing the spontaneous beauty of improvisation.

Elaine May poses for a portrait in a bowling alley in New York City, 1961.

(Ed Feingersh / Michael Ochs Archives / Getty Images)

In Elaine May’s The Heartbreak Kid (1972), Lenny and Lila are a pair of newlyweds on their way to Florida for their honeymoon. As they have breakfast at a diner, Lenny notices something about Lila that he never had before—not an especially surprising occurrence, considering how hastily he rushed them into marriage after only a brief relationship, as a means of circumventing her sexual morals. He’s already been showing signs of regret as the close quarters of the trip force him to actually get to know her a little; her predilection for snacking on Milky Way bars in bed is especially grating for him. At the diner, though, what really bothers him is how she eats.

Books in review

Miss May Does Not Exist: The Life and Work of Elaine May, Hollywood’s Hidden Genius

Buy this bookMay shoots this pivotal scene like a horror movie, starting off with a tight close-up of Lenny as he watches Lila with a dawning look of revulsion, leading up to the shocking jump scare: a reverse shot of Lila’s face smeared with egg salad from her sandwich. May is unsparing in her disdain for the masculine self-absorption that leads Lenny to then start an affair with a college student. What’s perhaps more surprising is that Lila doesn’t escape May’s scorn either. As May portrays her here, she really does look a little grotesque. And the barely concealed horror on Lenny’s face is counterpointed by Lila’s total obliviousness as she continues to devour the egg salad. Throughout the rest of the film, Lila’s naïveté will continue to serve as the butt of the joke, such that Lenny’s growing antipathy toward her starts to look, if not justifiable, at least not quite so gratuitous.

That May seems almost to relish depicting Lila like this is particularly striking in light of a fact about her that is mentioned throughout Carrie Courogen’s new biography, Miss May Does Not Exist: Like Lila, May was a notoriously messy eater. She spilled huge quantities of crumbs all over herself whenever she ate; an assistant sometimes helped pick out the food that was, unbeknownst to her, strewn throughout her hair. Even decades later, May’s contemporaries delighted in stories of her barbaric gustatory habits—perhaps because of how much they contrasted with her public image. After her Broadway show with Mike Nichols, a string of loosely scripted comedy sketches and improv acts, rocketed her to celebrity status, May looked like the very embodiment of literate and urbane sophistication. She generated an almost otherworldly air of mystique; according to the actor Richard Burton, she was “one of the most intelligent, beautiful, and witty women I had ever met.” This string of superlatives was a typical reaction to her tendency to bulldoze over innocent bystanders who could only look sadly average in comparison.

But her abhorrent table manners, in addition to bringing her down to earth somewhat, injected an element of autobiography into her distinctly unsympathetic portrayal of Lila. And the fact that Lila was played by May’s own daughter, Jeannie Berlin, only added to the self-critique. Messy eating also looms large in May’s debut film, A New Leaf (1971), in which the hapless heroine is marked as a social outcast by her tendency to get crumbs everywhere, earning the derision of the high-society onlookers around her—she was played by none other than May herself. May’s imperiousness seems to have been a reaction in part to her harsh and peripatetic upbringing; forced to fend for herself, and relegated to outsider status as a Jewish woman, she learned the value of self-sufficiency early. While the Olympian diffidence that resulted sometimes manifested itself as cruelty toward her characters, she was also capable of tempering it with a surprisingly vulnerable and self-deprecating tone. If May had no shortage of scorn to go around, she always had second helpings for herself.

It’s nevertheless undeniable that, in both her work and her life, May made few compromises on behalf of others. She was born in 1932 and spent much of her early childhood on the road. Her father was a Yiddish theater actor who was trying to string together a living from odd gigs, sometimes bringing May onstage for bit parts. When he suddenly died of a heart attack when May was 11, she and her mother moved in with her mobbed-up uncle in Chicago, where she enjoyed a front-row seat to his wayward business schemes. These formative experiences in Jewish and then Italian immigrant communities would leave their mark on May, infusing her films with the hustle and nervy energy of the ethnic enclaves she grew up in; she ended up making a mob movie of her own, Mikey and Nicky (1976). Her family eventually found their way to Los Angeles, where May married at 16, had a daughter a year later, and then separated from her husband. After she heard that the University of Chicago would allow her to attend despite not having a high school degree, she left a 3-year-old Jeannie behind in LA to hitchhike there with $7 in her pocket.

When May arrived, she declined to enroll officially, instead attending the occasional class while falling in with a group of aspiring actors and writers and immersing herself in the campus’s experimental theater scene. She wrote scripts in which she honed her acerbic wit and pitch-black humor, and she helped invent improvisational comedy in the process, laying the foundations of the genre for Second City and Saturday Night Live. (The “four rules” of improv often attributed to Del Close were in fact first drafted by May.) Famously irascible, she once responded to a pair of catcallers who shouted “Fuck you!” at her by asking, “With what?” After meeting Mike Nichols—he was introduced to her as “the only other person on campus who is as hostile as you are”—the pair developed the stage show that would become a huge hit when they brought it to New York, eventually landing a headlining gig on Broadway in 1960.

There were tensions within the partnership from the beginning. Nichols was a neurotic perfectionist, and May chafed against his preference for repeating their safer routine acts, insisting that they embrace the chaos of improvisation from night to night. After only a year of being on Broadway, May abruptly walked away from the show out of dissatisfaction with how ossified their formerly spontaneous improvisations had become. The conflict between her integrity and the concessions demanded by commercialism had become too untenable. She would continue to apply that same degree of artistic stringency to her subsequent projects. After a decade of bouncing between theater work and bit parts in movies, May began her directing career with A New Leaf in 1971 and quickly developed a reputation as an obstinate collaborator; as the lead actor in that film, Walter Mathau, put it, “Elaine is one of those brilliant, brilliant people who’s a terrific pain in the neck because she’s crazy. She’s a full-fledged nut.”

Exclamations like these litter Courogen’s meticulously researched biography: May provoked a strong opinion, whether positive or negative, from nearly everyone who encountered her. In the decades since May’s fourth and final film, Ishtar (1987), those reactions have metastasized into her legacy, often overshadowing the films themselves. Something about her elicits, even requires, this kind of mythologization—which can make her slim body of work, comprising only four feature films, look like a mere annex to her colorful public persona.

This problem is embodied most fully by the infamous production disaster on Ishtar, the film that ended her directing career. Ishtar started out as a favor to her from Warren Beatty, who agreed to produce and star in May’s next film in return for her sterling fixes to the script of his own film Reds, a 1981 biopic documenting the life of the communist journalist John Reed. Beatty soon found himself in over his head. On location in the Moroccan desert, May spared no expense to get the shots she wanted: At one point, she allegedly decided that she didn’t like the look of a hilly stretch of sand dunes and asked for them to be flattened. She clashed repeatedly with her stars and crew, including Beatty and his then-girlfriend, the French actress Isabelle Adjani, and tinkered with the footage in a post-production process that stretched on for 10 months. Before it was even released, the film suffered a spate of bad press about its extravagant cost and May’s eccentricities on set, painting her as fickle and incompetent. When the film flopped, it turned her into an industry pariah who hasn’t made another film to this day. (Although that didn’t stop Hollywood from using her services as an often-uncredited script doctor on other people’s movies.)

One particular sticking point, with the studios picking up the tab, was her method of simply leaving the camera running and refusing to cut during takes. As a crew member on Ishtar put it, “Elaine May is a woman of many words. However, the word ‘cut’ does not happen to be among them.” (The film ended up with four and a half days’ worth of raw footage to be edited.) This habit was likely born out of May’s blasé attitude toward technical limitations—the analog cameras of the time could only shoot for around 10 minutes before running out of film—and it created headaches for the coterie of embattled cinematographers who constantly had to warn her that the camera was about to run out of film. But her capriciousness was likely guided by a deeper principle. At one point during the filming of Mikey and Nicky, a relentlessly dark buddy comedy starring John Cassavetes and Peter Falk, the cinematographer—under strict instructions from May never to cut unless she said so—simply let the camera run out of film as the actors continued to improvise. When one of them eventually asked if the cameras were still rolling, May didn’t even care that the answer was no. Something she retained from her time doing improv was a taste for the thrill of the spontaneous dynamics emerging between actors; seeing them in the moment like an aurora borealis was the whole point for her, and capturing them on celluloid was only a secondary consideration.

May’s choice of egg salad as the food for Lila to gorge on at the diner in The Heartbreak Kid is innocuous enough at first glance, but as the film progresses, it’s revealed to be just one element in an expanding mosaic of ethnic signifiers. May’s Jewish background seems to have imparted an acute sensitivity to the subtleties of racial difference—those coded details that speak volumes to those who know what to listen or look for. It means something, for example, that Lenny is from New York City—or at least it means something to the suspicious parents of Kelly, the all-American blond girl he meets on the beach during his honeymoon, who clearly interpret the place he’s from as further evidence of his swarthy unfitness to date their daughter. May evinces a deep familiarity with the peculiar kind of abductive reasoning that gets deployed in the search for proof of ethnic origins: the kind that seizes on minute details and brazenly extrapolates their larger significance.

When Lenny pursues Kelly to her family’s home in Minnesota, May depicts the locale as an impregnable fortress of rectitude, by turns WASPy and Nordic, reinforcing its austerity by filling the background with as many white and blond extras as she could find. (The casting call was protested by the area’s Native Americans as racist.) Lenny refuses to give in to the family’s stonewalling, pestering them until the father explodes in a diatribe whose undertones of chauvinistic disdain are barely concealed: “Do ideas like that just come into that New York head of yours?” he asks. “Did you honestly think you could come out here and wise-guy yourself a girl like Kelly?” Although the epithets drip with racialized loathing, they’re perched just on the edge of plausible deniability; what sets the film apart from Philip Roth’s much blunter treatment of similar subject matter in Portnoy’s Complaint is that the ethnic valence of the romance is never explicitly mentioned. But Lenny himself gives the game away when he finds out Kelly’s last name: “Of course a girl like you has a name like Kelly Corcoran.” Against the backdrop of Lila’s egg salad, it doesn’t take a detective to figure out what he means.

Lenny’s journey from New York to Minnesota, and from Lila to Kelly, is thus a journey out of Jewishness itself. As the middle stop in this journey, Florida lends itself well to the kind of racialized paranoia that the film delights in sending up, and May would continue to map the state’s social geography in her script for The Birdcage (1996), directed by her former improv partner Nichols. The son of a gay couple living in South Beach, a Miami neighborhood known for its drag clubs, pleads with his parents (played by Robin Williams and Nathan Lane) to hide their relationship from the conservative family of the girl he wants to marry. They also need to hide their Jewishness, pretending that their last name is Coleman instead of Goldman. For the girl’s Republican parents, who vacation on Fisher Island with Jeb Bush, the difference couldn’t be more important. But when one of the son’s fathers shows up to dinner in drag, pretending to be the family matriarch, the girl’s father is not only taken in but utterly enchanted: “They don’t make women like that anymore!” he exclaims. This right-wing politician is made into a buffoon by the disparity between what he doesn’t know and what the viewer does—and it’s in this dramatic irony that May’s unmistakable authorial voice pierces through.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →The essence of her comedy resides in this kind of disparity in knowledge, which she lords over her characters almost contemptuously. That attitude toward her fictional creations seems to have been an extension of her attitude toward people more generally—the product of an outsize and uncompromising personality that has taken on a mythic stature in the intervening years. Replete with vivid anecdotes, Courogen’s book provides ample evidence to bolster that myth, as well as contributing to the effort to reframe its political significance. When May was still making films, she was derided for her intractability and then shut out of Hollywood; since then, the narrative has ricocheted in the opposite direction, celebrating her refusal to give in to the demands of a misogynistic industry.

Into this discursive fray enters Courogen’s biography, dedicated to “difficult girls” and vociferously on the side of the revisionists. Sometimes, though, Courogen’s reverence for her subject leads her to take some speculative leaps. At one point, in describing May’s manic on-set methods, she hypothesizes that “not asking for help and insisting on doing it all yourself aren’t the actions of someone tough. They’re the actions of someone scared.” Although this attempt to humanize May is well-intentioned, it tends to be undermined by the many examples, presented by Courogen herself, of the sheer force of May’s personality. It also displays the broader impulse to assimilate May into a narrative: Her colorful, sometimes baffling behavior always needs to be explained, whether it’s as that of a difficult woman, or an uncompromising artist, or a frightened waif.

The sensibility that’s crystallized in May’s films is both more acerbic and more surprising than any of those standard biographical templates allow. Nowhere is this more evident than in the infamous film that killed her career, whose unexpected subtleties and flashes of tenderness have endured far more gracefully than the furor it kicked up on its release. Ishtar’s protagonists, Chuck and Lyle (played by Beatty and Dustin Hoffman), are aspiring singer-songwriters, cheerfully unaware of how bad they are at what they do. May delights in allowing them to make fools of themselves as they excitedly workshop song lyrics that epitomize a vapid person’s idea of profound insight: “Telling the truth can be dangerous business / Honest and popular don’t go hand in hand / If you admit that you can play the accordion / No one’ll hire you in a rock and roll band.”

Like so many of May’s characters, Chuck and Lyle are ensconced in an impenetrable cocoon of obliviousness. Here, though, their idiocy turns out to have geopolitical stakes, once they go on a tour to Morocco and become entangled in a conflict involving communist revolutionaries and the CIA. Somehow, they manage to come out on top. At the film’s close, Chuck and Lyle are headlining their own tour, which is bankrolled by the CIA as part of a truce deal; an officer orders the soldiers in the audience to clap for them. Also watching them is the beautiful revolutionary whom they’ve picked up along the way—and as they fire up another of their insipid songs, she tearfully professes: “I think they’re wonderful.” This swooning confession borders on the deranged, which makes it easy to interpret as yet another instance of May mocking her characters. In a way, though, May is taking her seriously. May’s films dwell in the yawning chasm between our perception of her hapless characters and their deluded perceptions of themselves, wringing comedy from our knowledge of what those characters fail to see. But in this moment, she also posits that inhabiting a shared delusion with someone else is as close to a happy ending as you can get.

More from The Nation

The Peculiar Case of Ignatius Donnelly The Peculiar Case of Ignatius Donnelly

The Minnesota politician presents a riddle for historians. He was a beloved populist but also a crackpot conspiracist. Were his politics tainted by his strange beliefs?

The Agony of Aaron Rodgers The Agony of Aaron Rodgers

Is he the world’s most interesting athlete or is he just a washed-up crackpot?

Can You Understand Ireland Through One Family’s Terrible Secret? Can You Understand Ireland Through One Family’s Terrible Secret?

In Missing Persons, Clair Wills's intimate story of institutionalized Irish women and children, shows how a family's history and a nation’s history run in parallel.

Peter Schjeldahl’s Pleasure Principle Peter Schjeldahl’s Pleasure Principle

His art criticism fixated on the narcissism of the entire enterprise. But over six decades, his work proved that a critic could be an artist too.

How the Western Literary Canon Made the World Worse How the Western Literary Canon Made the World Worse

A talk with Dionne Brand about her recent book, Salvage, which looks at how the classic texts of Anglo-American fiction helped abet the crimes of capitalism, colonialism, and more...

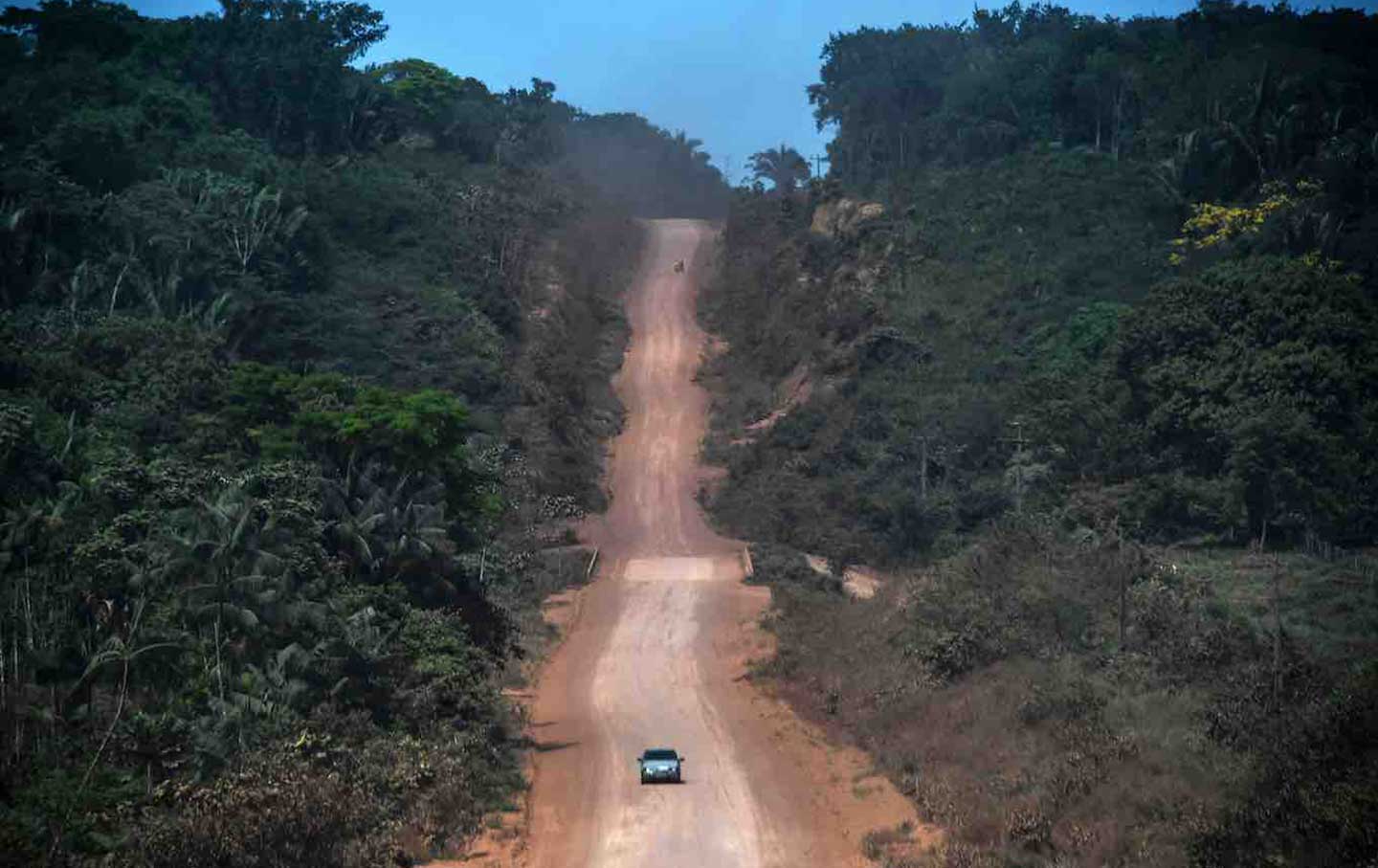

Along the Roads That Built Modern Brazil Along the Roads That Built Modern Brazil

José Henrique Bortoluci's What Is Mine tells the story of his country’s laborers, like his father, who built its infrastructure, and in turn its fractious politics.