Reading Mumbo Jumbo in the Post-Covid Age

Reading “Mumbo Jumbo” in the Post-Covid Age

Ishmael Reed’s novel depicts an American government dedicated to public health as long as its efforts keep hierarchy and the status quo in place.

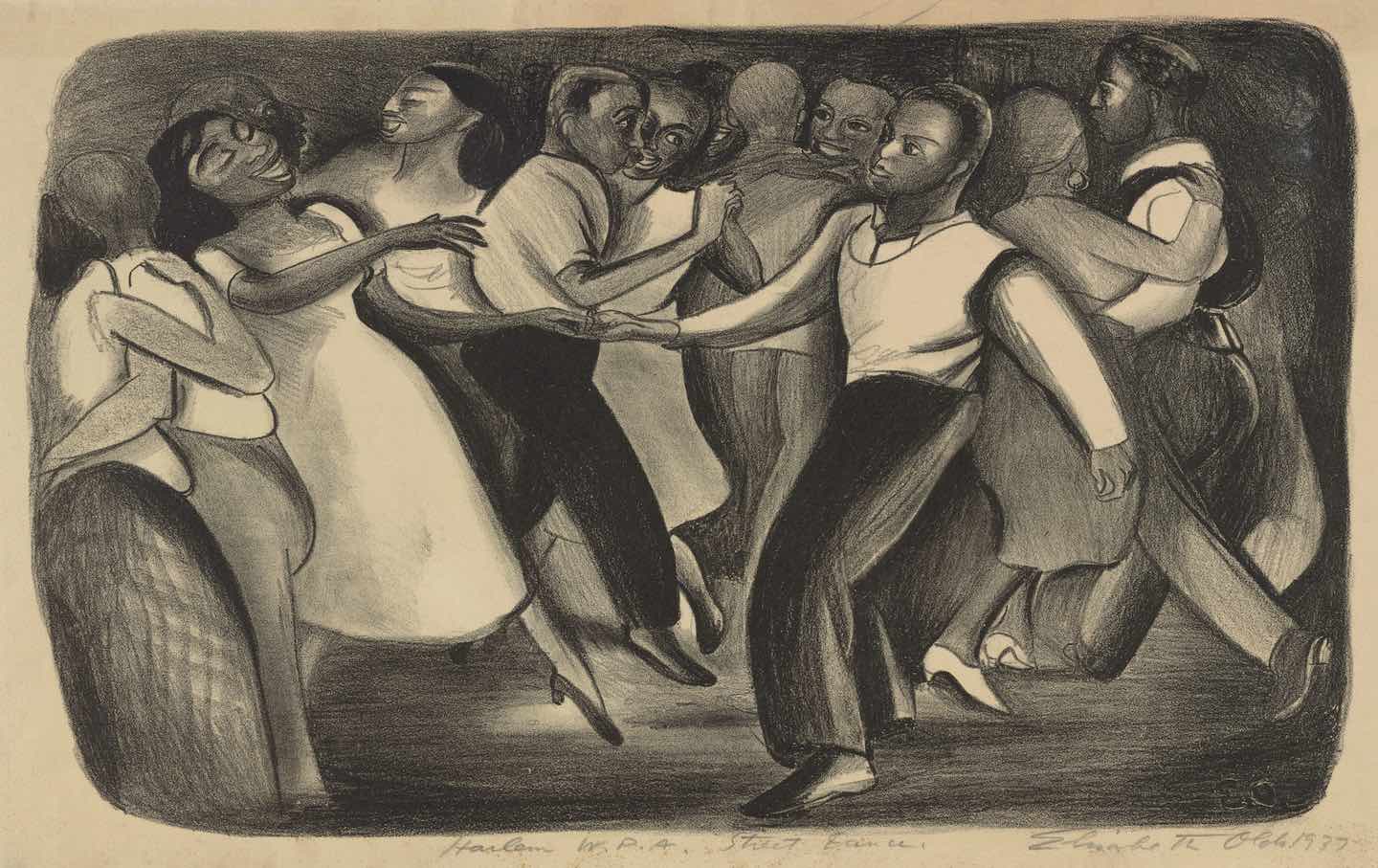

Harlem WPA Street Dance, by Elizabeth Olds, ca.1935–43.

(Photo by Heritage Art / Heritage Images via Getty Images)The first cases were reported in New Orleans sometime in the 1920s. Young people’s bodies were reportedly shaking out of control, and it was very clear that some foreign contagion was responsible. The city’s elders took notice, and soon the alarm sped up the ladder to the Wallflower Order, a group of concerned citizens who kept in touch with officials at all levels of government. The contagion had been previously seen in Haiti, and the Order had advised the United States to send some representatives there to stop the spread. But when the disease broke out stateside, it became clear that more drastic measures needed to be taken.

And so, in Ishmael Reed’s Mumbo Jumbo, the government pulls out all the stops to defeat this fearsome illness, known as Jes Grew. The primary symptoms are dancing and a sense of heightened revelry; presidential candidate Warren Harding is drafted to help bring the infected back to their senses. (Part of his platform is for America to be “done with Wiggle and Wobble.”) Soon Jes Grew appears in Kansas City and Chicago and starts creeping toward New York, where its taking hold would have dire consequences for the prospects of eradication. The Wallflower Order, a group whose power Reed defines as “those to whom no 1 ever asked, ‘May I have this 1?,’” is upset that things aren’t working, so they bring in Hinckle Von Vampton, a dormant member of the Knights Templar. After a bit of persuasion, he takes on the task of containing the illness; he spends much of the book in Harlem desperately searching for the proper inoculation against Jes Grew to spare Harlem’s Black population, a group especially vulnerable to infection.

In real life, the US government’s pandemic response, as we all know, was both fulsome and a failure. And as Mumbo Jumbo turned 50 last year, President Joe Biden declared the very much ongoing Covid-19 pandemic “over.” Even with a surge predicted in the coming months, Covid-19, we are told, isn’t a real problem any more as inflation, too-early campaign poll numbers, and other metrics have overtaken our fixation on how much coronavirus swirls among us. The government has often found itself seized with indecision as its various arms and levels argued over whether to pursue different measures designed to slow the disease’s spread, such as wearing face masks and—when the time came—inoculation against its worst effects. Yet in Reed’s universe, when the Wallflower Order realize that Harding isn’t doing enough to stop the spread of Jes Grew, they bring all their persuasion to bear to have him removed from power. (He’s assassinated.)

Ling Ma’s 2017 novel Severance became an oft-cited work during the pandemic for the way it portrayed the whimpering dissolution of civil society under prolonged, uncontrolled disease and a government that ceases to function in the face of a black-swan event. The opposite is true in Reed’s world, one where the powers-that-be are obsessed with ridding their world of the sickness that threatens it.

Of course, the Wallflower Order isn’t doing this public health work out of the goodness of its heart. Jes Grew doesn’t show up in the body as any sort of malady or pain, but as a libratory spirit—hence the sick moves. For the Order, the stakes of this pandemic gaining ground means that Western civilization itself will soon be under threat. And if they don’t get the Black populace under control by snuffing out this contagion, they might lose control of everything they’ve built up through centuries of violent domination. What makes Mumbo Jumbo so potent, in our supposedly post-pandemic era, is the picture it paints of the way the powerful jump into action to protect their interests. Whereas, in our world, neglect was the operative force, in Reed’s novel, public health becomes urgent if what’s at stake is hierarchy itself.

Mumbo Jumbo’s B-plot emphasizes just how pernicious this entrenched hierarchy is. It involves a merry band of multicultural art thieves called the Mu’tafikah—featuring Berbelang, who bristles at the idea that American Blacks aren’t sufficiently militant; Yellow Jack, who recalls fondly the glory of the Boxer Rebellion; and José Fuentes, who decries gringo exploitation—whose imperative is to repatriate pilfered art from Western museums. While everyone else in New York City is dancing or chasing a cure for Jes Grew, the Mu’tafikah are plotting a heist of the Art Storage Facility, which is guarded by a brutal, corrupt ex-cop. The danger of Jes Grew’s spread is paralleled by the Mu’tafikah’s recruitment of Thor Wintergreen, a rich white boy with a “swine Robber Baron of a father,” whose joining the group gives it the resources and connections it needs to finish the job. When a Mu’tafikah leader takes Thor aside for a rap session at a greasy spoon, the brute manning the counter threatens to make trouble; Thor notes that his father owns the diner, and suddenly the counterman begins offering top-tier service.

Meanwhile, Hinckle Von Vampton starts a tabloid magazine that he hopes will aid in the effort to mind-control Harlem’s populace into keeping themselves free of Jes Grew. His main rival in the quest to understand the virus is Papa Labas, a voodoo man who is far more tolerant of spirits loosening and altering human behavior. “In 1920 Jes Grew swept through this country and whether they liked it or not Americans were confronted with the choices of whether to Eagle Rock or Buzzard Swoop, whether to join the contagion or quarantine it,” he says at one point during a lecture on Jes Grew’s spread. As the scholar Michael Chaney has argued, although the symptoms of Reed’s fictional disease are physical, “Jes Grew conflates virological associations with information, transmissions of black culture, blackness itself, and Hoodoo possession.”

The name “Jes Grew” itself calls back to James Weldon Johnson’s research on Black music and how its well-traveled classics “jes’ grew” into their full forms as bits and pieces of them traveled throughout the country. Madeleine Monson-Rosen reminds us that Mumbo Jumbo fits within a literary tradition stretching from Charles Dickens’s Bleak House to Richard Preston’s The Hot Zone, all indulging in our fear of unstoppable sickness. But Reed wraps into this fear other (white) worries of what happens when Black people get too itchy in their oppression, as in jazz music, cakewalk dances, or slave rebellions.

Jes Grew, a biological and informational virus, takes hold of its hosts and changes their tune about the way they live their lives and find their leisure. It doesn’t have to be this way, they realize. (Early on, Reed describes Jes Grew as an “anti-plague.”) These are the expressions that the Wallflower Order can’t stand, so it attacks the illness in order to rid society of the symptoms. Last year, the writers Beatrice Adler-Bolton and Artie Vierkant published an essay called “The Beyblade Strategy,” which tracked the slow degradation of anti-Covid infrastructure since the start of the pandemic and argued that the US government began caring less and less about curbing infections as soon as it realized that the novel coronavirus was merely an endemic threat instead of an existential one—which meant getting back to “normal” as soon as possible. In order to get people back to work, back to spending money, the government has slowly given up a program of stopping the spread and shifted the burden from its immense shoulders onto our tiny ones. There will be no urgent emissaries dispatched to put an end to what is no longer deemed a problem. Since the Biden administration ended its emergency pandemic declaration, it has become harder and more expensive to protect oneself from getting sick, even as the quality and quantity of information available to understand the full picture of mass infection has been steadily reduced.

The US government, in its approach to Covid, took the exact opposite direction from the Wallflower Order. Through its killing and disabling, the Covid pandemic created the conditions for people to realize the shortcomings of the lives they had been living. They began to seek ways to care for one another; they joined unions; they rioted. But because the United States’ ruling crust has always been fine with throwing wide swaths of its charges onto the pyre of order, it only cared to stamp out the new expressions of spiritual and political health that Covid had created. It decided that we could live with a disease that debilitates the body politic as long as the head retains its function and place.