Freedom Furniture

How did Americans come to love “mid-century modern”?

How Did Americans Come to Love “Mid-Century Modern”?

Solving the riddle of America’s obsession with postwar design and furniture.

Type the words “mid-century modern” or “Danish Modern” into the search bar on Facebook Marketplace, and you’re just as likely to see a fat floral sofa as you are a sleek credenza. A search for “MCM” on Craigslist in the New York City area returns listings for, among other things, a lamp whose base is composed of chrome-plated spheres; a set of two oak chairs with square backs; and a painting most likely made by someone at a class where they were drinking wine as they wielded their brush. We all know what actual mid-century modern furniture looks like: expanses of teak, tables resting on hairpin legs, brass hardware, and natural finishes, as well as wool upholstery in shades of olive, ocher, and orange. The items for sale online are not any of that, but the term proliferates anyway—MCM furniture is what people want to buy.

Books in review

The Chieftain and the Chair: The Rise of Danish Design in Postwar America

Buy this bookFor some 15 years, mid-century modern has been a staple at vintage shops, at estate sales, and in the online stores that sell similarly styled pieces. The take-off of the trend is hard to pinpoint precisely, but it coincides with two disparate phenomena: the premiere of AMC’s Mad Men in July of 2007 and the Great Recession, which arguably started only five months later. While the latter spurred in Americans a nostalgia for the booming economy of the postwar era, the former showed them exactly what that era looked like. Every Sunday night, there it was: the clothes, the hairstyles, the accessories, and, crucially, the interiors—apartments on the Upper East Side, houses in Ossining, and brand-new offices in Midtown.

Soon, companies jumped on the mid-century bandwagon. Banana Republic launched a 1960s collection: slim-fitting suits with skinny ties and sheath dresses with white piping. So did Estée Lauder: lipsticks and nail polishes and powders in various saturations of rosy pink, all in gold packaging. The furniture giant West Elm looked to cash in too, producing dozens of MCM-inspired pieces. (A search for “mid-century” right now on the West Elm website yields some 400 results.) Most notoriously, in 2014, the Williams Sonoma–owned company started producing a splayed-legged, square-cushioned sofa called “the Peggy,” after Mad Men’s most popular female character. The Peggy, which retailed for around $1,200, was a veritable disaster of furniture design. After an essay by Anna Hezel in The Awl (titled “Why Does This One Couch From West Elm Suck So Much?”) went viral in early 2017, the company started offering full refunds to anyone who’d purchased it. But West Elm’s other MCM items continued to sell by the container load.

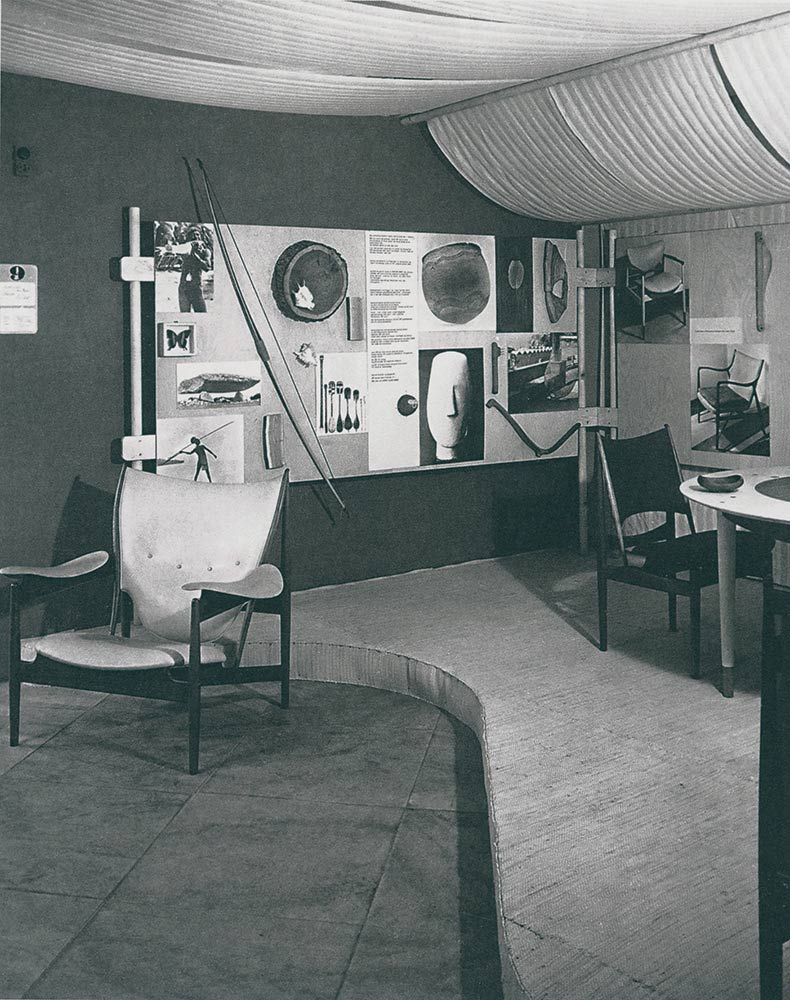

Maggie Taft’s new book, The Chieftain and the Chair: The Rise of Danish Design in Postwar America, ends where the above story begins. Her aim is to examine where those teak expanses and hairpin legs came from in the first place. Taft explores the history of Danish modern design through two pieces of furniture: Hans Wegner’s Round Chair, better known as simply “the Chair,” and Finn Juhl’s Chieftain reading chair. The former is a basic dining chair, designed as part of a set, whose defining element is a single, semicircular wooden form that serves as both back and armrests—hence the “Round” in its moniker. The latter is a cushioned chair upholstered in leather, with wide armrests and a high, regal back rising above its seat. Their differences—the Chair’s slight size and the Chieftain’s heftiness; the Chair’s huge popularity in America and the Chieftain’s relative lack thereof; Juhl’s architectural education and Wegner’s training in cabinetmaking—allow Taft to develop a succinct but multilayered history of Danish Modernism.

During and after the Second World War, Taft tells her readers, a pair of schools in Copenhagen—one training architects and the other cabinetmakers—formed the center of gravity for Danish design. Juhl had attended the demanding and prestigious Kongelige Danske Kunstakademi, Arkitektskole (Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, School of Architecture), graduating in 1934. Around that same year, Wegner moved to Copenhagen from his hometown of Tønder, where he had worked for three years as a journeyman in a cabinetmaking shop run by Hermann Friedrich Nicolaus Stahlberg. As people moved from the countryside to the cities (and thus from houses to apartments) during and after the war, a new generation of Danish designers focused on creating pieces of furniture that could fit easily into small spaces and were adapted to the realities of postwar urban life. By the early 1950s, designers and furniture makers in all of the Nordic countries—not just Denmark—had ventured forth in search of new markets. Pooling their resources, they first targeted consumers in the rest of Europe. Eventually they found in the United States a growing base of customers with deepening pockets who, thanks to government assistance, were purchasing larger homes that they needed to furnish.

In order to fill all those homes with Danish furniture, however, the makers and producers had to find ways to get people in the US to buy it. So they employed what Taft calls “tastemakers”—magazine editors, architects, and curators, among others—to help sell the style. Danish Modern furniture, according to the story these tastemakers told, was simple and long-lasting, humble yet refined. It was built for urban and urbane living, but it could also be purchased by the masses—thoughtful, tasteful, and perfect for those with small apartments. “Even the poorest Dane” could afford it, reported a Cincinnati Post article quoted by Taft. Yet none of that was close to the truth: From the outset, mid-century modern furniture was not for anyone but the well-off. The designs were delicate and often mannered, and the pieces were out of the financial reach of the vast majority of Danes—most of whom still outfitted their homes in the bulkier neoclassical styles—as well as most consumers elsewhere in Europe and the United States. But the idea that this furniture was long-lasting and already hugely popular took hold regardless, helping to boost its reputation among American tastemakers and consumers alike.

Despite the gap between marketing and reality, Wegner’s Chair eventually became so ubiquitous in the US that the demand far exceeded the capabilities of the workshop, owned by cabinetmaker Johannes Hansen, that produced it. As Taft explains:

When the Chicagoans called, they didn’t want just four chairs. They wanted four hundred. [But] Hansen couldn’t fill the order. Like most cabinetmakers, his operation was small. He had only five craftsmen in his workshop, too few to make so many chairs in any reasonable time frame. And then there was the matter of credit: Hansen would need a down payment to secure the materials and labor needed for so large an order, while Americans were accustomed to a forty-day grace period between placing an order and the first payment coming due.

A new program of mass production had to be introduced. Eventually, American manufacturers moved in to fill the production gap. The furniture manufacturer Baker hired Finn Juhl to design its Baker Modern line, and he made changes to his earlier classic designs (such as the Chieftain) to make them easier to manufacture on a large scale and to distinguish from their Danish counterparts. Instead of teak—widely used in Denmark because of that country’s colonial relationship with Thailand, where it grows natively—Baker chose American walnut. The Chieftain’s horned vertical back supports—originally produced by the cabinetmaker Niels Vodder with a step joint, a sophisticated move that allows two pieces of wood to meet at an acute angle—were elongated to maintain the overall shape while simplifying the joinery process. It was at this point that Danish Modern started to become all-American, leading to the eventual conflation of the terms “Danish Modern” and “mid-century modern.”

By the late 1950s, almost every American furniture company had a Danish line. “Advertised as ‘Copenhagen Danish Modern’ (Lane), ‘Danish-inspired’ and ‘Royal Dane’ (Bassett), and ‘truly Danish-Modern’ (Stakmore), these American furniture sets borrowed certain features common among Danish imports—for example, all were made of wood—and codified them, helping to create a popular sense of Danish design and what it looked like,” Taft writes. In this way, Danish Modern became a hallmark of the American century and American power.

At the first televised US presidential debate in 1960, John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon sat in Round Chairs. Danish Modern was presented as a symbol of the luxury, freedom, and stylishness afforded by the capitalist development with which America had become politically synonymous; it was now as American as democracy itself. This association, however questionable, became an important element of the furniture’s appeal—and of the marketing campaigns to sell it. Danish Modern was, in ad copy and in the words of the era’s tastemakers, furniture for all Americans. “It is a significant part of the Wegner story,” wrote House Beautiful editor Marion Gough (as quoted by Taft), “that people were ‘discovering’ this beauty even before the experts stamped it with their approval.” Wegner’s Chair belonged, at least in theory, to anyone and everyone.

Danish cabinetmakers, American manufacturers, and tastemakers like Doris Scherbak—an American whose husband was stationed in Paris to work on the Marshall Plan—popularized not just the specific pieces of Danish Modern furniture but the very idea of it. Curved lines, splayed legs, rich wood: These became emblematic of the idealized, placid mid-century American lifestyle made possible by the outrageous growth of capitalism. Since the high cost of producing those emblems kept them out of reach of a number of Americans, capitalist ingenuity saw an opportunity to satisfy its profit motive: Copies and knock-offs proliferated in the United States, where copyright rules were lax to the point of nonexistence. Even Scherbak, who had outfitted her apartment in Paris entirely with furniture and fabrics from the Danish store Den Permanente, bought a pair of knock-off chairs in Mexico and proudly wrote to Fischer that she was “happy to have” them, because they were “really good copies and were so very cheap.”

As these copies and knock-offs filled the market, design integrity and quality suffered. Take, for example, a collapsible chair designed by Wegner, with two notches on its underside for hanging when folded. Numerous manufacturers reproduced it as a fixed chair but retained the notches, turning them into a purely decorative element. Or consider the proliferation of curved chairbacks that emulated the Chair’s back and armrests. Designed to enable the joining of two rectangular blocks of wood, the Chair’s unique curve was a crucial part of its engineering, not an aesthetic decision but a structural one. The makers of the Chair’s many knock-offs kept the curve not because they were reproducing the Chair itself as a crafted, engineered object, but because they were reproducing the Chair as an idea, embodied by an image. If we subscribe to the adage that form follows function, then the reason that copycat designs looked the way they did is because the look made them salable.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →I am tempted here to return not to Mad Men but to another piece of prestige television from an earlier era: Sex and the City. In the middle of the show’s run, when Carrie’s column is being optioned for a film in which Matthew McConaughey is apparently set to play Mr. Big, Carrie and the girls end up on a trip to Los Angeles. Once there, Samantha takes Carrie to a backyard in the Valley, where a man opens a trunk to reveal a mass of fake Fendis encased in thin, off-gassing, transparent plastic. Carrie purses her lips into a “no”—they’re very nice, but she doesn’t want them because they are fake. The originals conferred the appearance of something: status, good taste, and, above all, wealth. The fakes would communicate the same thing to everyone but their owners, who’d know they were a sham. That wasn’t good enough for Carrie.

Things have certainly changed. In the world of purses and bags, the market is saturated with fakes to such an extent that there are now prestige fakes more highly sought after than other run-of-the-mill fakes, and perhaps even more than the originals themselves. “Authenticity” is increasingly elusive at a time when replicas of the Chair far outnumber the originals. In the furniture world, the mainstream public is so removed from the fact that pieces are designed by specific people that, outside of specialist circles, there might as well be no such thing as an original.

Taft’s story culminates in a hall of mirrors: Once American manufacturers started producing their own Danish-style designs, Danish furniture makers started copying them. Danish originals gave way to American copies, which gave way to American originals, which gave way to Danish copies of the American originals, and so on and so forth. The furniture objects became a representation of the marketing and advertising slogans that the originals had inspired. And so we’re back to where we started. The 21st-century popularity of MCM-style furniture surely has to do with Mad Men’s aesthetic appeal and a recession-fueled nostalgia for the years of the postwar boom, but it might have even more to do with the very thorough and very successful decades-long marketing campaign for Danish Modern design. During a time of scarcity and strife—and yet another war—rich wood tones, hairpin legs, and wool upholstery could serve as a respite without veering into ostentation. The narrative had been long established, and the evidence for it could be found not just on TV but also in catalogs, photographs, and advertisements: MCM furniture was luxurious yet restrained, beautiful yet sober, unique yet egalitarian. It promised, through the simple act of buying, the image of a better life. In this way, it has never been a symbol of freedom or democracy, but rather of the way capitalism pushes people to treat consumption as the only way to achieve a different reality.

More from The Nation

The Agony of Aaron Rodgers The Agony of Aaron Rodgers

Is he the world’s most interesting athlete or is he just a washed-up crackpot?

Can You Understand Ireland Through One Family’s Terrible Secret? Can You Understand Ireland Through One Family’s Terrible Secret?

In Missing Persons, Clair Wills's intimate story of institutionalized Irish women and children, shows how a family's history and a nation’s history run in parallel.

Peter Schjeldahl’s Pleasure Principle Peter Schjeldahl’s Pleasure Principle

His art criticism fixated on the narcissism of the entire enterprise. But over six decades, his work proved that a critic could be an artist too.

How the Western Literary Canon Made the World Worse How the Western Literary Canon Made the World Worse

A talk with Dionne Brand about her recent book, Salvage, which looks at how the classic texts of Anglo-American fiction helped abet the crimes of capitalism, colonialism, and more...

Along the Roads That Built Modern Brazil Along the Roads That Built Modern Brazil

José Henrique Bortoluci's What Is Mine tells the story of his country’s laborers, like his father, who built its infrastructure, and in turn its fractious politics.

The Long History of the "Elsewhere Museum" The Long History of the "Elsewhere Museum"

Can the ethnographic museum be reinvented?