The Grand Delusions of “Marty Supreme”

Josh Safdie’s first solo effort, an antic sports movie, revels in a darker side of the American dream.

One of the great animating forces in the American psyche is self-delusion. Maybe it’s something we pick up because others wear it well, like slang or fashion; maybe it’s an adaptation that emerged to handle cognitive dissonance, to reconcile the American subject’s promise of liberty with their immediate experience of lack. Our scammer tales are as rich and delicious as folklore, populated with as many stock characters: cult leaders, con men, pyramid schemers, reality-TV stars, hustlers, grifters, Anna Delveys, and Bernie Madoffs. Perhaps we care about these figures out of reverence for the golden few who are vindicated—those who at first seem delusional, then bend reality to conform to their self-image.

Filmmakers and brothers Josh and Bennie Safdie work within this rich history, with a particular specialty in neurotic, twitchy, down bad men who are clinging to a desperate hope that they’re one stunt away from changing their luck. This study reached its apotheosis in Uncut Gems (2019), starring Adam Sandler as a diamond dealer’s pursuit of the biggest gambling win of his life. Uncut Gems was a boon for the brothers; it put them on the map, leading to a TV series with Nathan Fielder and acting roles for Benny (in Oppenheimer and Licorice Pizza) and greater notoriety for Josh. Last year, the brothers confirmed that they are no longer codirecting films, and Marty Supreme is Josh’s first solo project since.

Marty Supreme starts off like a standard sports drama: Marty, played by Timothée Chalamet, is megalomaniacally devoted to table tennis and chafes at his responsibilities to his sick mother (Fran Drescher); his uncle Murray (music journalist Larry “Ratso” Sloman), who employs him at his shoe store; and his pregnant, married lover Rachel (Odessa A’Zion). (Like Adrian in Rocky, Rachel works at a pet shop.) Everything comes second to his dream of taking ping-pong mainstream, with himself as its figurehead. An unexpected loss to Japanese star Koto Endo (Koto Kawaguchi) sets back his plans—and Marty’s unsanctioned stay at a five-star hotel on the International Table Tennis Association tab incurs a $1,500 fine, which Marty needs to pay before he can challenge Endo again at the next world championship in Tokyo. At that match, he hopes to cement his place as the best table tennis player in the world.

Marty can find that much money quickly only through semilegal means, and we’re off on the frenetic ride the Safdies are known for. Marty hauls ass out of windows as he flees the police, masterminds a dog-ransom scheme, and gets shot at in rural New Jersey; at one point, he steals a necklace off the neck of rich, bored retired actress Kay Stone (Gwenyth Paltrow) while they’re having sex in the shower and drops it down the drain to retrieve later. The film’s real core, the sequence depicts hustling as Marty’s real talent: the art of never-ending arbitrage, leveraging each small lucky break toward a bigger and bigger payday. That this produces a cascade of escalating disasters doesn’t dissuade him—it’s all in pursuit of greatness, and if he achieves greatness, it was all worth it.

It goes without saying that Marty is an asshole. But at a certain point, he’s moving from scheme to scheme too quickly for the consequences to register—he becomes, by the climax of his effort to get the money for Tokyo, almost a mythological figure, like a maenad or minor nature spirit: gleeful, morbid, and invulnerable, pulling from some esoteric well of energy and governed by a set of physical and psychological limitations different from everyone else’s. No real person could take this many hits and keep going, but then you realize that rolling from one humiliation to the next is precisely what makes him invincible.

Although Marty is megalomaniacal, he doesn’t work alone. To achieve his aims, he strip-mines the goodwill of anyone who shows affection toward him: In addition to his family, he ropes in his friend and fellow ping-pong hustler Wally (Tyler Okonma, aka Tyler, the Creator), and ping-pong fan Dion, whom he had previously involved in a scheme to produce Marty Mauser–branded orange balls. Nearly everyone turns out the worse for it—Marty never borrows a car without crashing it—but it doesn’t imperil his ties to his friends and family, which define him as much as he strains against them. At one point, Murray hires a cop to scare Marty as payback for taking $700 from a safe, and as the intimidation tactic wraps up, uncle and nephew exchange a quick “I love you” to gloss things over.

Harder to charm are Kay and her husband, pen magnate Milton Rockwell (Kevin O’Leary of Shark Tank fame); Rockwell will settle Marty’s debts and get him to Tokyo, but only if he throws an exhibition match and loses to Endo. Marty and Kay are holed up in a hotel room when she interrogates his plans for table tennis stardom: What will he do if things don’t work out? “That doesn’t even enter my consciousness,” he responds. What better avatar for our time? You too can live this way if you jam certain frequencies from beaming contradictory information to your brain. Marty Supreme shows that there’s great freedom in not just aspiring to wealth or fame or power but believing in a future in which you’ve already achieved it. If you seem severely overleveraged in the present, it’s simply because you’re borrowing against the riches that are sure to come.

Whether this is detestable or heroic depends on the teller. Marty bets the house on himself again and again, and there’s something romantic and compelling in believing in a dream so deeply that you’d allow it to destroy you. But belief and destruction are promiscuous; even if you summon them for a narrow purpose, they tend to breach their circumscribed bounds. Marty is willing to destroy more than himself, and infinite belief is a powerful fuel that avails itself to so many projects. The belief itself becomes essential, because if it wanes, everything that has come before needs to find a new justification. If you’re going to fuck someone over anyway, why not believe in it?

Early in the film, Marty’s tennis table rival, Endo, is presented as his mirror image: as coolheaded and disciplined as Marty is mercurial. His victory at the British Open and Marty’s ensuing meltdown helps cement Endo as a star in Japan: no better foil than a raging, entitled American. Getting himself to Japan to challenge Endo again motivates Marty for much of the film—it inspires the car chases, stolen dogs, and miscellaneous ping-pong-related violence—but Tokyo is rendered with so much less specificity and color than Marty’s New York that it feels like we’ve traveled from the real world to a painted set. Marty is there to “entertain the Japanese people so they buy more of my pens,” per Rockwell, which is exactly as anticlimactic as it sounds.

The Japanese crowd and Japanese characters are rendered in only the broadest strokes—we learn nothing about what motivates Endo, whether he feels a similarly all-consuming passion for table tennis, what he’s sacrificed to get to the top, how he feels about the swaggering vulnerability of his rival. Both Endo and the actor who plays him, Koto Kawaguchi, are hearing-impaired, a detail you could miss for how superficially it figures in the narrative. As for the Japanese audience, they really love table tennis and want Endo to win; that’s about it. It’s a waste to create a character who so memorably expresses an essentially American mode of charismatic self-justification, then send him to Japan in 1952 and have nothing happen.

While touring the world as a halftime act for the Harlem Globetrotters, Marty visits Egypt and chips off a piece of the pyramids to bring back to his mother. “We built this,” he says, pressing it into her hand. He has an acute awareness of his history as the subject of genocidal violence, both historical and so recent that the wounds are still raw. In his compulsive pursuit of the next big break, you also sense the reflexes of someone traumatized by American capitalism—the fact that it enthralls him only reinforces the point. In the close focus of the Lower East Side, Marty is an underdog, David going up against Goliath and refusing to be shaken.

But Marty’s goal is world domination—that’s what motivates him, why he fought so hard to get to Tokyo. Who he becomes when the structures that limited him fall away is the natural question—but at the moment when we would have most to gain from seeing the ramifications of his worldview, the film stays firmly within his perspective. In going abroad, he learns nothing more than how good it feels to stand up for himself. The foreign stage is the backdrop for his self-actualization, and when things go wrong, he simply catches a ride back home on a military plane. That’s the American dream.

More from The Nation

Has Contemporary Fiction Ignored the Working Class? Has Contemporary Fiction Ignored the Working Class?

Claire Baglin’s bracing On the Clock gives its readers a close look at work behind the fry station, and in the process asks what experiences are missing from mainstream letters.

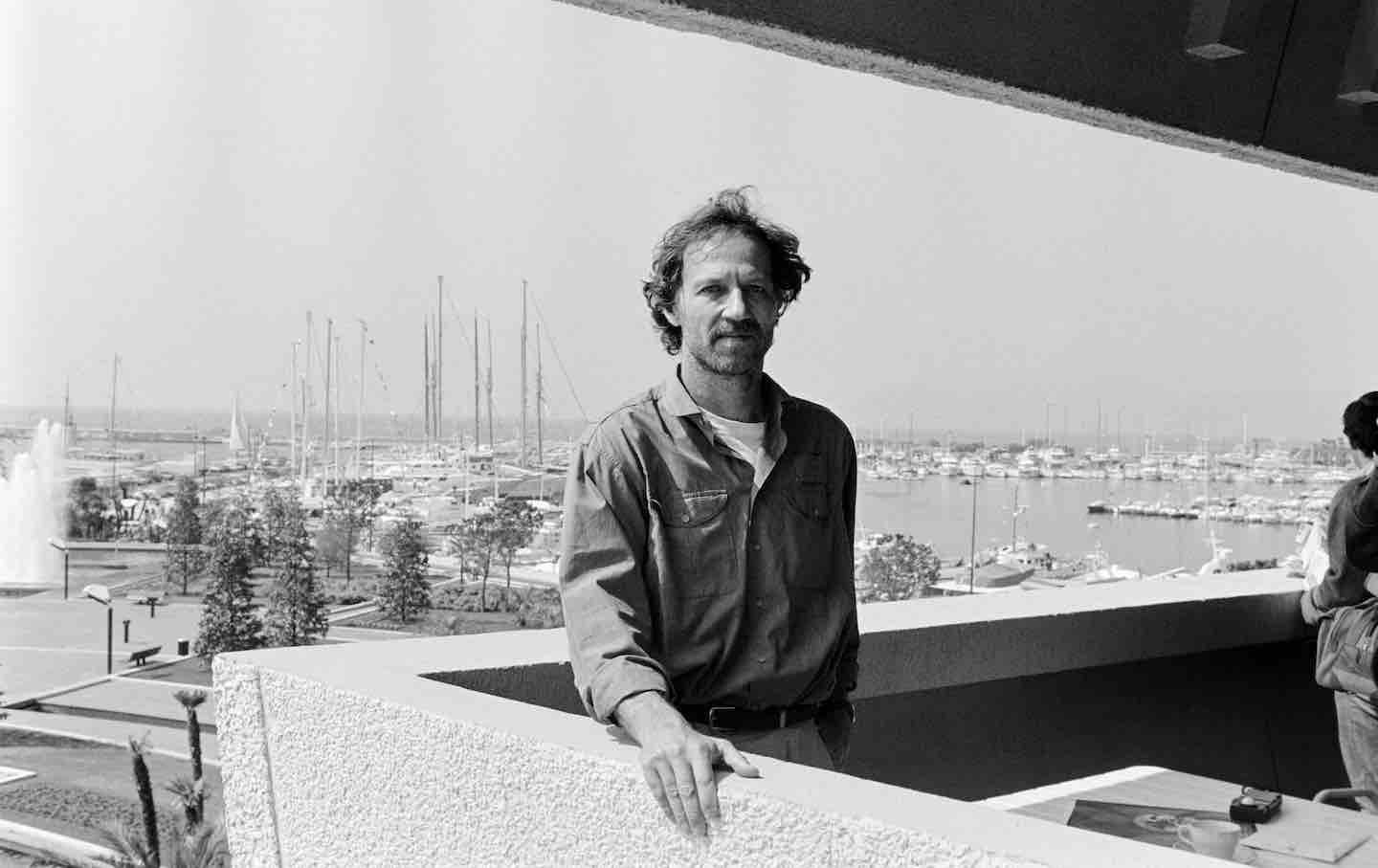

Werner Herzog Between Fact and Fiction Werner Herzog Between Fact and Fiction

The German auteur’s recent book presents a strange, idiosyncratic vision of the concept of “truth,” one that defines how he sees the world and his art.

Do Humans Really Understand the World’s Disorderly Rivers? Do Humans Really Understand the World’s Disorderly Rivers?

In James C. Scott’s last book, In Praise of Floods, he questions the limits of human hegemony and our misplaced sense that we have any control over the Earth’s depleted watershed....

The Scramble for Lithium The Scramble for Lithium

Thea Riofrancos’s Extraction tells the story of how a critical mineral became the focus of a worldwide battle over the future of green energy and, by extension, capitalism.

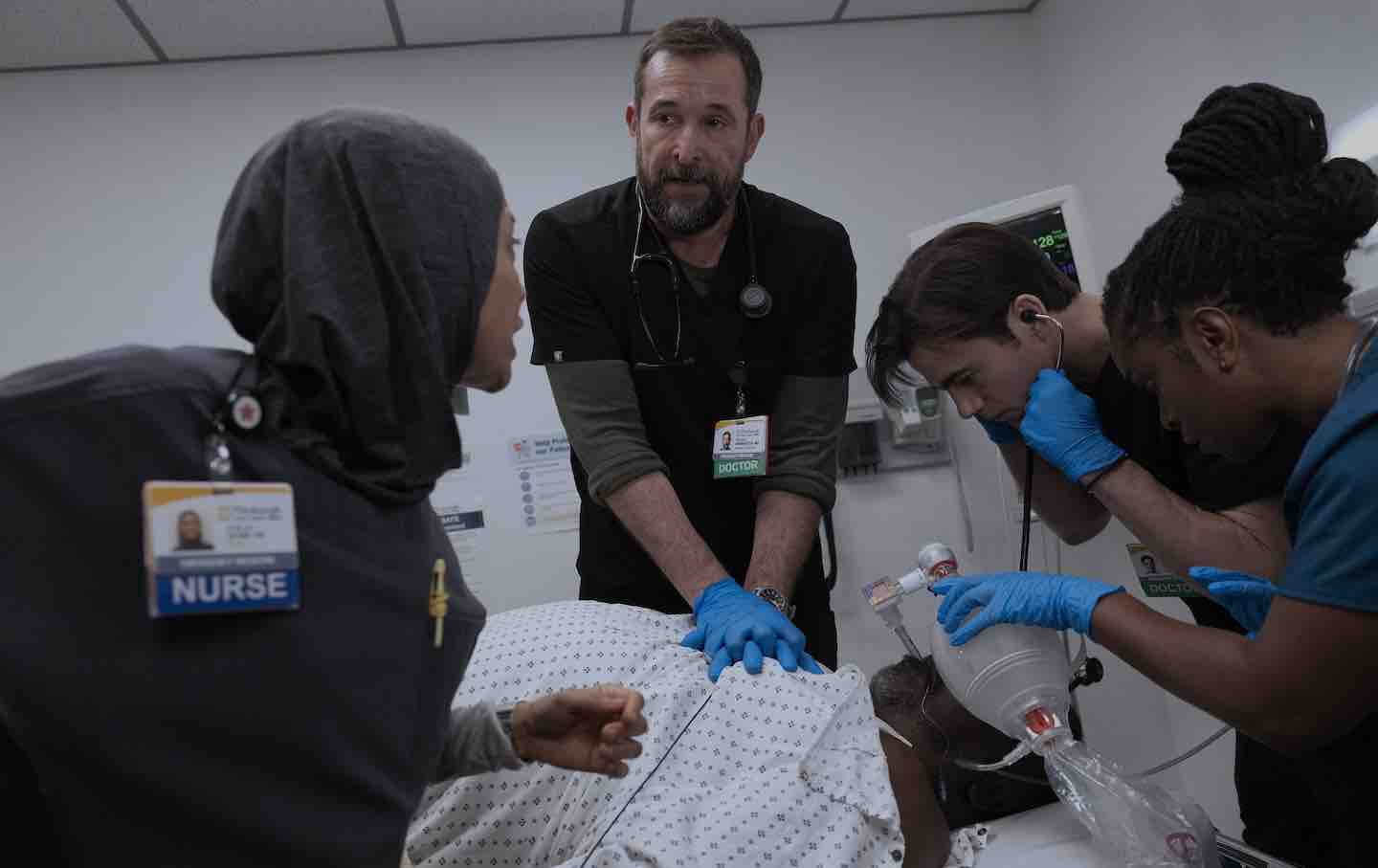

“The Pitt” Shows Doctoring Uncensored “The Pitt” Shows Doctoring Uncensored

The second season tackles everything from the role of AI in medicine to Medicaid cuts. But above all, it is about burnout.