I think Lucinda Williams came into my life through an act of fate: My dad had picked up a CD of her 2003 album, World Without Tears, at a garage sale, and it soon became one of the few that lived in the glove compartment of the family minivan. For years, that CD played on repeat, and Williams’s doleful, sultry wail would carry us through high mountains and low deserts, through tired silences and back-seat brawls.

It took recovering from my preteen antagonism to fully admit the sheer prowess and sonic versatility of those songs, as well as those that appear on Williams’s 13 other albums, for that matter. Because her music blends the ambience of blues with the candid narratives of country and the cool fervor of rock, it can accommodate any mood, any landscape.

The chameleonic ease of Williams’s discography is an indirect outcome of her itinerant childhood. She was born in 1953 in Lake Charles, La., to Lucille Fern Day and the late, lauded poet Miller Williams, whose search for an ever-elusive professorship meant that the family moved almost yearly. While Williams speaks, in her new memoir, Don’t Tell Anybody the Secrets I Told You, to the influence that living in places like Mexico City and Santiago, Chile, had on her intellectual sensibilities, she maintains that she’s still Southern to the core. Both of her grandfathers were Methodist ministers — one in Louisiana and the other in Arkansas — and she writes fondly of her paternal grandparents’ efforts to forge racial equity, despite the tyranny of Jim Crow, within their church.

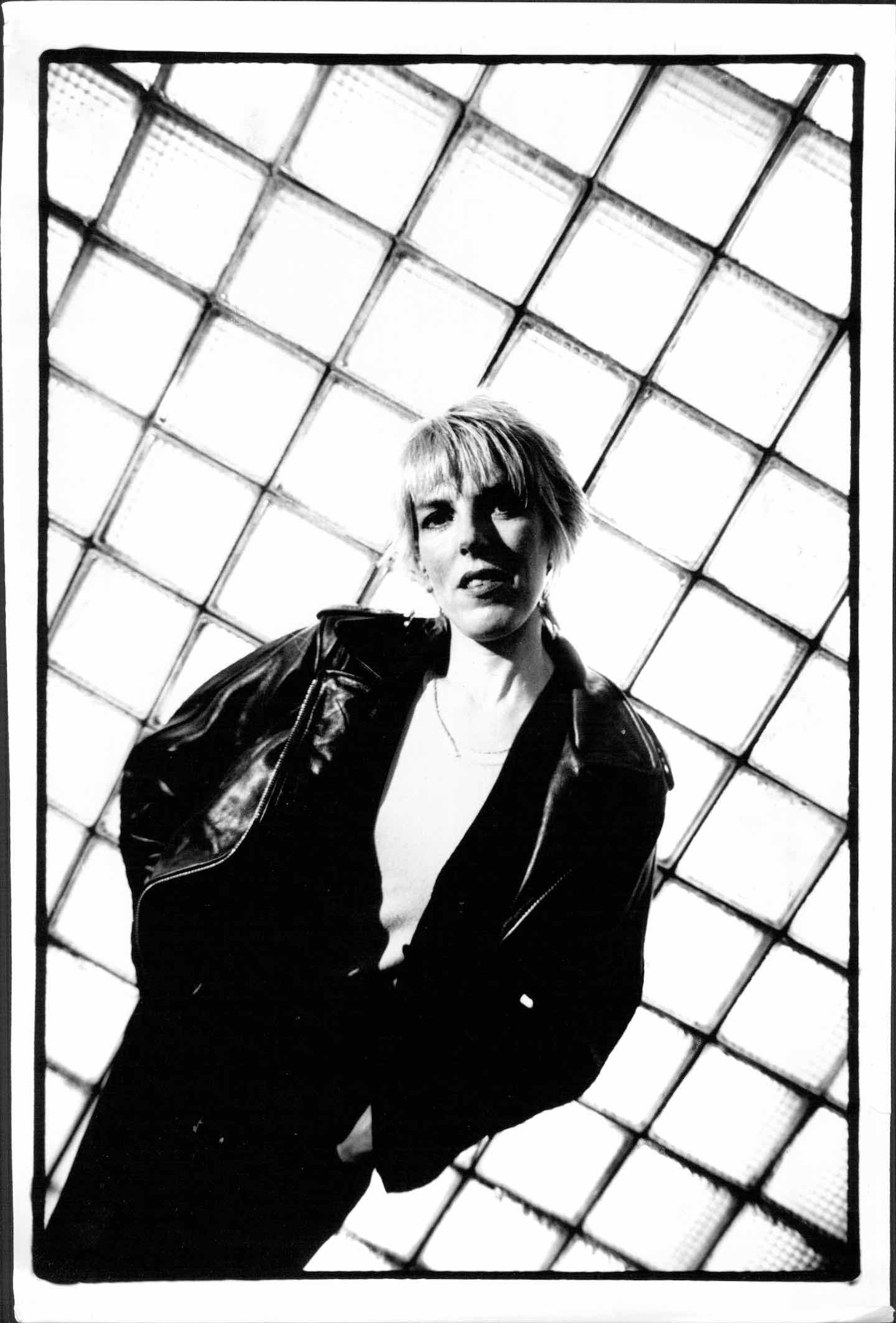

Williams’s memoir, like the sum of her songs, offers enough richness and breadth to afford multiple focal points. Read one way, the book is an intellectual history: Starting at a young age, Williams had frequent brushes with many great writers, musicians, and activists of the day. Read another, it’s the sobering confession of a woman whose mother’s battle with mental illness and substance abuse took an emotional toll — and, later, of the prolonged difficulties she faced in a ruthlessly commercialized music industry that sought to pigeonhole her. Still, Williams is as compassionate as she is honest. In our recent conversation, she spoke openly about her personal struggles and political convictions, as well as her commitment to making music that doesn’t shy away from darkness. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

—Emma Hager

Emma Hager: What was it like to put your life to paper in such an extended, detailed way when you were writing the memoir?

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

Lucinda Williams: It was difficult. I’d never written a book before. One of the problems that I ran into was, after the fact, remembering things that I forgot to put in there. I kept finding things that I wanted to change, or amend, or correct. I guess that impulse is in my blood, because that’s what my dad would do.

When I was learning how to write, my father taught me about the economics of writing. He also told me not to fall back on too many clichés, like “the moon in June” or “the stars in your eyes”—that kind of thing. He would say, “Try to find a better way to say it, instead of falling back on the same old tired, clichéd phrases.”

EH: I knew something about your background and how you were often surrounded by writers, but I was still so surprised upon reading the book, because it functions in part like a Rolodex of all the great 20th-century writers. You had brushes with all of those people!

LW: Oh, yeah, all those writers came through town!

EH: There’s one anecdote that I think perfectly captures the literary climate at your family home during those days: Charles Bukowski attended a party there and then ended up writing about it later on. Do you remember which book of his that gathering makes a cameo in?

LW: Yeah, Bukowski wrote a book called Women, and in it he talks about going to a professor’s house for a party after a reading. And then my dad told me about Charles Bukowski being at one of the parties one time, after a reading, and I put the two things together and realized, “Wow, he’s talking about a party at our house!”

EH: You rely heavily on references to the Southern Gothic literary mode to tell your story. I’m wondering how these qualities—eerie relations to place; a general sense of unease, angst, isolation—help frame or clarify your early childhood experiences for you?

LW: Well, when I first read some of the Southern Gothic writers, like Flannery O’Conner and Eudora Welty, I just loved their work and identified with it immediately. It felt very recognizable—I think I felt like some of my own family members and people I’d encountered growing up were mirrored in their characters. My vision of the world was similar to what those writers were talking about. I just understood it.

You know, I asked my dad one time to define his understanding of “Southern Gothic” for me, and he did. I wish I remembered what he’d said, because it was perfect, of course, and the term is so hard to define.

EH: Being a Southerner seems a complicated but generative identity for you, and the book covers much of your own work as an activist, in addition to your family’s contributions to the civil rights movement.

LW: I think my need to fight for what’s right runs in the family. My grandfather—my father’s father—was a Methodist minister, and he was a Christian in the true sense of the word: He talked the talk and walked the walk. He and my grandmother were very much vocal about the racism they’d run up against in his church. They advocated for racial integration within the church. He was also involved in the Southern Tenant Farmers Union. You’d have these sharecroppers, and they’d work this farmland, but then the money they’d made would go to the owner of the land, so it was almost like slavery. And then they finally unionized, and my grandfather got involved in supporting that union and helping the farmers unionize. He considered himself a democratic socialist.

We forget how bad things were back then, just socially, in the towns across the country. But anyway, I think I inherited some of that fortitude and resilience from them. And my dad was like that, too. He became best friends with George Haley—the brother of Alex Haley—in college, and when I was born, George became my godfather. But my dad used to tell stories about when he and George Haley were friends, back in the 1950s and 1960s, walking around campus together, and they would get bags of urine thrown at them, and racial slurs would be used as they walked by—all that stuff.

And I can remember, when I was in high school in New Orleans in the 1960s, seeing “Whites Only” signs. One time, my boyfriend at the time and I got on our bicycles, rode to one of those signs that somebody had written, and we spray-painted over it.

At an early age, I got involved in civil disobedience, and demonstrations and marches and all of that. I loved the feeling of being with others of like mind, of knowing that it was us against them, and that we’re marching onward and doing something to change things… or at least it felt like we were doing something to change things! Nothing feels as good as singing “We Shall Overcome” with a bunch of strangers; even though you don’t know the others personally, you have this strong common ground.

I also got drawn into all the music of the movement, too—the protest songs, Bob Dylan and Joan Baez. I would learn those songs, and I would go play my guitar and sing those songs at different demonstrations. When I was in high school, I would stand out in front of the grocery store and hand out “Boycott Grapes” leaflets in support of the farm workers in California who were being led by Cesar Chavez. It was either when we lived in Mexico or when we lived in Santiago, Chile, that I had posters of Che Guevara all over the walls of my bedroom. I was drawn to the rebels and the fighters.

EH: Which came first, your awareness of racial and class conflict, or your interest in the popular protest songs surrounding civil rights movements?

LW: I think my awareness of those issues came first, and then the protest songs. But that’s a good question. I mean, I was reading a lot—like, for example, when I was in high school, I read The Autobiography of Malcolm X, as well as Eldridge Cleaver’s Soul on Ice. And also, just talking with people in our family’s circle… I learned a lot that way.

EH: Correct me if you disagree, but I feel like your 2020 album, Good Souls Better Angels, is your most overtly political album thus far. Those songs spoke directly to the aftermath of Trump’s election and the cultural atmosphere of the country more generally. Were you hesitant to make potentially polarizing statements before that, or was there something about the moment that called for it? How did that album come about?

LW: Pretty much every day there was something in the news on TV, or in the newspaper, that would be shocking, disturbing, and make you so angry. It was a daily occurrence. Dealing with Trump’s antics was enough right there! So I had to get all that anger out, I had to deal with it—and that’s why I write to begin with, to sort through things and get it out of my system. The writing process is therapeutic. I was writing about all those feelings because they came up so much, and there were too many upsetting events. Plus for years I’d been wanting to write more songs like those—topical songs, the way Bob Dylan had, and also Pete Seeger, Woody Guthrie. Bob Dylan was the best at it, I think. It’s actually hard to write those kinds of songs without sounding too maudlin or mushy or something. But there were so many great topical songs being written when I first started playing guitar and singing. Bob Dylan’s “Masters of War” is the ultimate anti-war song, and I learned that one.

EH: What is it about Dylan’s version of the protest or the anti-war song that makes it the best to you?

LW: For me, it’s because he’s able to write his mind without being overly romantic or overly flowery. He doesn’t do all the “Let’s all hold hands and dance in a circle” stuff; he keeps it interesting, and he’s obviously read a lot and appreciates history. He’ll put lines in his songs that make biblical references or cite some piece of historical information. This all comes through in his songwriting. When you go back and look at his songs, they’re just really so well-written—even his early ones! Take “Blowin’ in the Wind”—at first, you might think, “Well, that’s a sort of simple song,” or “It has this almost childlike image about it.” But it’s a great song when you really sit there and start taking it apart and looking at the lyrics individually—it’s brilliant! That was one of the first songs I ever learned how to sing. It’s hard to write songs like that, ones with great lyrics and great melodies.

EH: Let’s switch gears a bit and talk about your long and sometimes fraught relationship to genre—or, more so, the labels that others have pinned to you. As you point out, guys like Bob Dylan and Neil Young were basically permitted to experiment—to make music that flirted with all genres—without being implored to pick a lane. But you had a very different experience with those classifications.

LW: By the time I was at that stage and was looking for a record deal and everything, the music business had changed somewhat from the time when Dylan and Young had started recording. It really had become more of a business, I think, by the time I rolled around. And, just like in any business, record labels have marketing departments, and the proper marketing of the product becomes the most important thing. As in: How are we going to get this out to people? How are we going to advertise it, get the message across, and get people to buy the product? So, right from the get-go, they were confused about what my style was, and they all asked: “What is this? We’re not sure what to do with this!” In the mid-1980s, I made this demo tape, and it fell into the hands of Columbia Records in Los Angeles, and they said it was “too country for rock,” so they ended up sending the tape to Columbia Records in Nashville, and those folks said it was “too rock for country.” Literally! I mean, I quite literally fell in the cracks between country and rock. That made my chances of getting a record deal a lot slimmer.

Eventually, someone came up with the idea of “Americana” music, which I think was really just another marketing ploy for the record labels to be able to put music somewhere. This way, it was easier for them to deal with the radio stations and all that, since many of them began to open up slots to play songs in that new genre.

EH: But you really resist the labels of “Americana” and also “alt-country,” even though people credit the existence of your music with shaping those categories. Does your opposition stem from a skepticism of the industry’s marketing apparatus writ large, or is there something else at play there?

LW: Yeah, I probably just got tired of all the marketing stuff that could affect every aspect of music-making. Like, here’s an example: I was asked to go to this radio music convention in Boulder, Colo., to perform. It was mostly radio-station people who would be there, so it was to capture their attention, and maybe a few record-label people as well. And some guy—probably a marketing guy—at my record label at the time said, “We’d rather you not wear the cowboy hat.” Sometimes I’d wear a cowboy hat… big deal! It wasn’t to create an image, even; it was just that I liked to wear cowboy hats—

EH: Well, cowboy hats are sexy. It’s very simple!

LW: Exactly, yes, they are sexy—thank you! Basically, this marketing guy told me that since my music is between country and rock, if I wore a cowboy hat, all the radio-station jockeys would think I was a country artist, which would mess everything up. That’s how far it went.

EH: Do you think that any of the excessively vigilant marketing of you and your image was related to being a woman, or do you think that artists of all genders were experiencing a similar level of scrutiny?

LW: I didn’t look at that as a gender thing, really; I think it was probably affecting all artists. When I was living in Los Angeles, I ran into a friend of mine who’d just gotten a really good record deal. I congratulated him, and he said, “Yeah, but Lucinda, they want me to fix my teeth! They don’t like my teeth, and they want me to get them fixed.” I think I said something like, “Fuck them!” What I’ll say is, I didn’t have perfect teeth, either, but they never asked me to fix them!

EH: In November of 2020, you suffered a stroke that has impacted aspects of your daily life, but I noticed that there was no mention of it in your memoir. The whole of it is so raw, so I’m curious about that omission.

LW: That’s an interesting question, especially since I do write about my whole life in the book. I did think, when I was writing, that I needed to cover my stroke; that’s part of what I’ve been through. But during crunch time, when I was supposed to meet one of my writing deadlines, the editors told me not to worry about writing about the stroke. Beyond that, I’m not really sure, but they seemed to think that since there was enough stuff in the book as is, it didn’t have to be in there. To some extent, they were trying to trim the book down, since it had gotten too long. We talked about that from the very beginning and even looked at other artist memoirs to see how long mine should be.

EH: Has your stroke, either on the physical or the emotional level, changed your relationship to any of your songs? Is there anything in your discography that feels harder or better to play, for any reason?

LW: That’s the million-dollar question—I can’t play guitar right now, you see. I’m having to relearn the guitar. For whatever reason, I’ve got some pain in my left hand when I try to press down on the strings, and so that presents a whole other hurdle that I’ll have to attack from some other place. My husband, Tom, keeps telling me that I have to try to play through the pain and that kind of thing, but that’s easier said than done. I’ve tried everything to get rid of the pain, but nothing’s really worked. The sensation is probably akin to having a little arthritis. I can still write, though, so during this time I’ve worked on a lot of lyrics. And if I’m working on a song, I can make out enough of the new chords to get by and come up with some kind of melody, which I then have to try to record so I don’t forget it.

EH: Lots of your songs are about loss in its various forms, but there seems to be a particular weight attributed to loss as it relates to substance abuse. The losses you cite can be literal—as in death—or more figurative, in the sense that someone might lose a part of themselves to, say, drugs or alcohol. What is it about this type of loss that carries such gravity with you?

LW: Simple answer is, I’m in the music world, and there are a lot of people like that. They’re gonna have more dramatic lives, more dramatic things happening… and, you know, create drama, which then feeds on itself, and that all feeds into the song. I think it can make for some interesting stories.

I guess I try to write about things that might be a little upsetting, or at least a little difficult to talk about—that’s always just been my MO. I write also about suicide, and death, and lust. I guess I enjoy writing about things that have maybe historically been considered taboo, especially for women.