Shortly after the spectacular collapse of Lehman Brothers in 2008 and the global recession that came tumbling after it, an Italian playwright named Stefano Massini began working on a fictionalized account of the men who’d founded the eponymous firm a century and a half earlier. I Capitoli del Crollo, or Chapters of the Fall, saw its first productions in 2010 on Italian stages, followed by performances on national radio. And then the play took off in various translations across Europe, drawing acclaim throughout the 2010s in France, Germany, Spain, and elsewhere. Despite its title, the play is mostly about the rise of Lehman Brothers; it follows three generations of Lehman men to tell a giddy tale about the growth of their bank and, by extension, rapacious American capitalism. In 2016, Massini published a 760-page expanded version, Qualcosa sui Lehman (Something About the Lehmans), which was billed as a novel and, like the playscript, was written in a sort of Homeric free verse befitting the epic ambitions of the project.

No doubt, part of the appeal of Massini’s work for directors was the open-ended nature of the play. Written in the third person, with no lines assigned to particular characters, it left theater artists free to shape their productions as they wished, even as they hewed to Massini’s script. Some European stagings used seven actors to play the Lehman men across the 164-year saga, as well as the dozens of other people they encountered; others used four or as many as 12.

The English adaptation by Ben Power—now called The Lehman Trilogy—uses three actors. Under the direction of Sam Mendes, it was a smash hit at London’s National Theater in 2018 and then in the West End. When it moved to the Park Avenue Armory in New York City the following year, tickets drew as much as $2,000 on the resale market—an almost too on-the-nose replication of the Lehmans’ own gleeful discovery in the play of the profitable manipulations of supply and demand.

The show was slated to move to Broadway in the spring of 2020. With the reopening of Broadway theaters after an 18-month shutdown, The Lehman Trilogy finally began performances this past October at the Nederlander, where it ran until January 2; it will begin a series of performances at the Center Theatre Group in Los Angeles in March. Meanwhile, an English translation of the novel (by Richard Dixon) came out last fall.

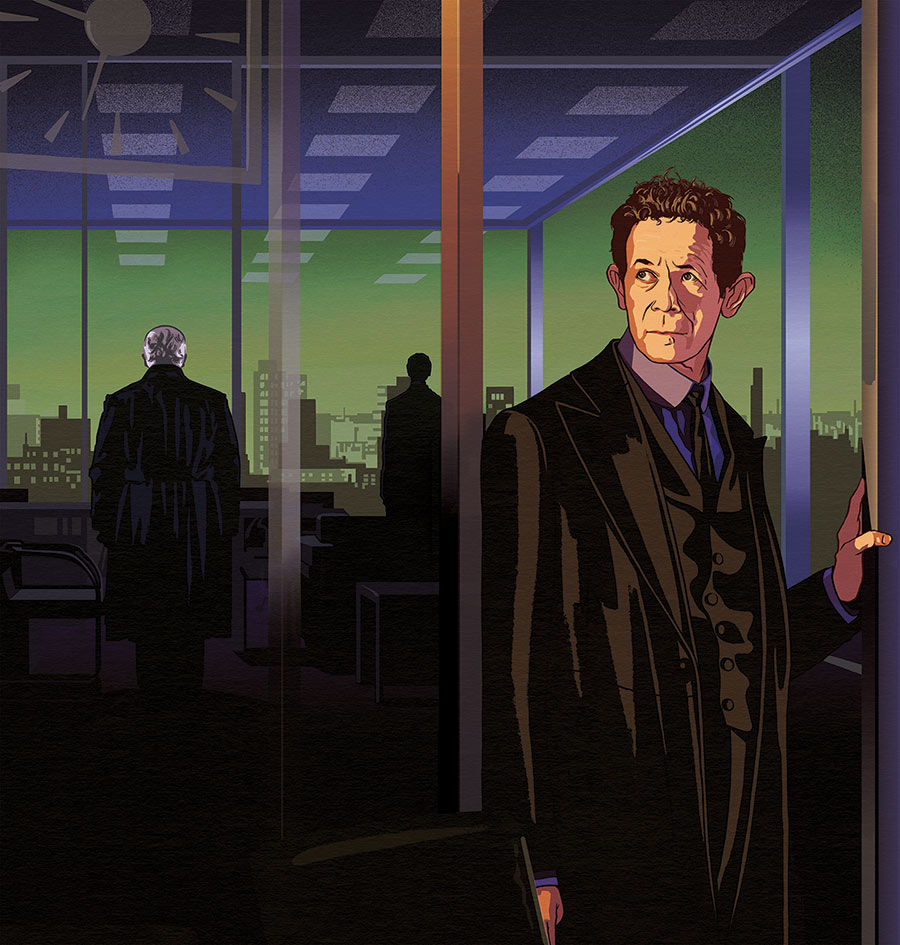

The terrific success of the show thus far makes sense on the level of glossy spectacle. Running about three and a quarter hours, the Mendes production zips along with surprising alacrity as three stellar actors—Simon Russell Beale, Adam Godley, and Adrian Lester—metamorphose into infants, elderly men, and everyone in between through shifts in stance, vocal pitch, cadence, and expression, without the aid of costume changes or props. The actors play within a rotating glass box, scrawling on its walls from time to time when, for example, they adjust the sign for their business to reflect its evolution from Alabama dry goods store to plantation cotton brokerage to international finance organ. Behind them, gorgeous photographic projections of New York Harbor, Southern cotton fields, the Manhattan skyline, and a chilling cascade of stock market numbers help set time, place, and mood.

The plot of The Lehman Trilogy runs on twin engines. One is an archetypal immigrant story: The forebears arrive, make good, and bestow fortune on the ever more assimilated generations who come after them. The other is a grand historical narrative about American wealth: Enterprising individuals earn riches, thereby nourishing a national economy based on private ownership. Both hackneyed story lines, of course, are myths, but it is in their interlinking that The Lehman Trilogy enters troubling territory. By tracing presumed economic progress—and destruction—through one family, the play suggests that broad political institutions and interests, as well as myriad other actors, have had little role in shaping American capitalism. What’s more, that Massini’s text dwells on the fact that this particular family is Jewish drives the work headlong into virulent stereotypes. Like a subprime mortgage, the play’s shiny seductions obscure the dangers within.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

The story starts (after a brief tableau set in 2008, as the firm is about to collapse) with Hayum Lehmann arriving from Bavaria in 1844. “He had been dreaming of America,” Hayum tells us of himself. (Because the text remains mostly in the third person, the action is narrated in cloying story-theater fashion rather than truly dramatized.) “The son of a cattle merchant, a circumcised Jew, with only one piece of luggage, stood as still as a telegraph pole, on Dock No. 4 in the port of New York. Thank God he’d arrived. Baruch HaShem!”

Soon a clueless immigration clerk changes “Hayum” to “Henry” and drops an “n” from his last name. Never mind that this cliché of customs agents rather than the immigrants themselves adjusting their names is historically unlikely (as the scholar Kirsten Fermaglich has demonstrated in A Rosenberg by Any Other Name), this opening does important work to set the audience’s attitude toward the three heroes—Henry is soon joined in America by brothers Emanuel and Mayer—establishing the Lehman clan as sympathetic, plucky newcomers who rise from pushcart to luxury through diligence, ingenuity, and model-immigrant perseverance.

As the play advances through the generations, it draws a parallel between two processes of deracination. The first relates to American capitalism. The brothers settle in Montgomery, Ala.; first they sell dry goods, then they deal in cotton, buying the raw material from local plantations and selling it to manufacturers up north. In 1858, they set up their own commodities firm on Wall Street. The second generation expands into coffee, petroleum, and other goods and then into selling securities to finance retail stores and railroads; the grandsons trade in the entertainment industry. Money becomes increasingly detached from tangible merchandise or infrastructure, and eventually, after the company falls out of family hands, Lehman Brothers deals in the thoroughly fantastical realm of credit default swaps.

Analogously, the play suggests, as money becomes more abstract through the years, the Lehmans’ ties to Judaism become more attenuated. When Henry succumbs to yellow fever in 1855, his two brothers close up shop for a week, rend their suits, and observe the prescribed month of mourning rituals. Decades later, when Emanuel dies in New York, the bank is closed for three days; 50 years later, when his son Philip dies, the firm observes just a couple of quick minutes of tribute. If the early Lehmans were pious and principled, the play suggests, Bobbie, a third-gen, art-collecting bon vivant and the last Lehman to head the firm (he died in 1969), has left such faith behind, his Jewishness now appallingly defined through his lust for lucre and domination. When he learns how marketing can persuade customers to “give us money they do not have for things they do not need,” he proclaims that the firm “will become all-powerful.”

The play labors to draw this arc of moral decline: The Lehmans’ admirable ambition, which underwrites the building of America, turns malignant when they abandon Judaism and begin to worship profit, going so far as to compare Wall Street to a divine miracle and the stock exchange to a synagogue. But that would-be moral arc is twisted, mangled, and bent. First, the Lehmans’ enterprise was malignant from the start: Its profits—like the national economy the Lehmans helped develop—depended on slavery. As Sven Beckert argues in Empire of Cotton, slavery was the “beating heart” of the burgeoning global economy that cotton spawned. Some cursory lines in the play make mention of this fact. After the Civil War—the two surviving Lehman brothers both supported the Confederacy—a local doctor tells Mayer that the South was bound to lose because “Everything that was built here was built on a crime. The roots run so deep you cannot see them, but the ground beneath our feet is poisoned.” But did Mayer really need to have this pointed out to him?

The play fails to mention that the Lehman shop stood opposite Montgomery’s central slave-auction block, and that Mayer himself had seven enslaved people in his household. That’s merely a fraction of the 1,250 enslaved people that J.P. Morgan acquired as capital, or the 13,000 that Morgan’s firm accepted as collateral while this ballyhooed hero of Wall Street was also forging monopolies, eating up small businesses, fixing prices, raking in millions, and wielding more power than the Lehmans ever caught scent of. Nonetheless, there is no J.P. Morgan in the play. There is no George Peabody either, and no Anthony Drexel, the Philadelphia financier and early mentor to Morgan. It’s as if the Lehmans alone created and perverted capital speculation and American investment banking. Massini narrows the world of Gilded Age capitalism and all that it wrought to the daring and avarice of a single Jewish dynasty.

Some reviewers have decried the play’s egregious neglect of the role of slavery in the Lehmans’ fortunes, but its constant harping on the family’s Jewishness has gone almost entirely unremarked on by the critical establishment, likely because the Jewish immigrant motifs it invokes are so ingrained as to be taken for granted. But the play gets many of them wrong. True, the members of the third generation were less religiously observant than their immigrant grandfathers, but assimilation moves along more jagged lines than the play recognizes. Perhaps Henry did affix a mezuzah to his doorpost in Montgomery and kiss it each time he entered his store. But at the same time, according to Stephen Birmingham’s 1967 book Our Crowd, the Lehmans of Montgomery quickly blended in, becoming “slave-owning, Southern-accented, and devotees of Southern cooking, even of…pork.”

Massini’s text and Mendes’s production mischaracterize what kind of Jews the Lehmans were as well. Whether this is out of ignorance or laziness or is a deliberate play for sentimental association is hard to say, but again and again The Lehman Trilogy aligns the Lehmans, who came from Germany, with the Eastern European Jews who migrated en masse to the United States between 1880 and 1920 by linking them to Eastern European Yiddish culture.

One can even hear this dubious connection in the music: A piano set just below the stage provides a soundtrack (composed by Nick Powell) throughout the production, silent-movie-style. A motif tinkles up when Henry disembarks in New York and returns whenever we are meant to recall the Lehmans’ origins: the melody of “Rozhinkes mit Mandlen,” a lullaby from a 19th-century Yiddish operetta that has assumed the status of folk song. It has nothing to do with German Jews, for whom Yiddish was not a primary language. What’s more, many of the German Jews who ran in the Lehmans’ circles deplored the “Ostjuden” and did everything they could to dissociate themselves from them. (In his novel, Massini goes even further, liberally sprinkling in Yiddish phrases.)

All this misplaced mishegoss underlines how the Lehmans’ Jewishness in the play is, at best, an instrument, a gauge for marking a disintegration of values and the disintegration of America itself. The play wants to critique the cruel intemperance of American finance that made Lehman Brothers implode, but the vast human consequences of that failure—the millions of Americans who lost their homes to foreclosure, for starters—aren’t considered here. So the tragedy we are presented with is one family’s tragedy, a family we are supposed to care about by dint of fond feelings for old bootstrap-yanking tropes and Yiddish lullabies, as well as the considerable charm of the actors.

One wonders why so many fine theater artists went to such elaborate ends to tell what amounts to a slender and dodgy story. The theater can certainly accommodate a trenchant and highly entertaining take on the finance industry amid the mayhem of deregulation, as Caryl Churchill showed in her great 1987 satire Serious Money, and it can also accommodate more complex and situated tales of entrepreneurial Jewish families amid an industrializing world, as in I.J. Singer’s The Brothers Ashkenazi, adapted for the Yiddish stage in 1937. The American theater has long been a space that welcomes a more textured exploration of Jewish assimilation—from Clifford Odets and Arthur Miller to Wendy Wasserstein, Donald Margulies, Deb Margolin, Tony Kushner, Lisa Kron, David Adjmi, Dan Fishback, and on and on and on.

The Lehman Trilogy, however, is not seriously interested in its own themes. It remains so narrowly concerned with the transactional lives of its protagonists that it can’t place them in history in any meaningful way. For the Lehmans, the Civil War is primarily an impediment to cotton sales (to thwart the Union blockade, they send goods to Europe); they survive the 1929 crash by keeping their heads down and refusing to help other banks, reasoning that if those take the fall, they might hang on. Not even the rise of Hitler in their ancestral homeland makes much of an impression, though they do note that war is good for business. Violence, chaos, disaster, and even genocide may swirl outside, but the Lehmans remain unperturbed, encased in that gleaming glass cube. What are we to make of this money-obsessed clan, so detached from the world that they pay no heed to the lives of others? The Lehman Trilogy offers no answer beyond one based on toxic derivatives.