Man’s Best Friend

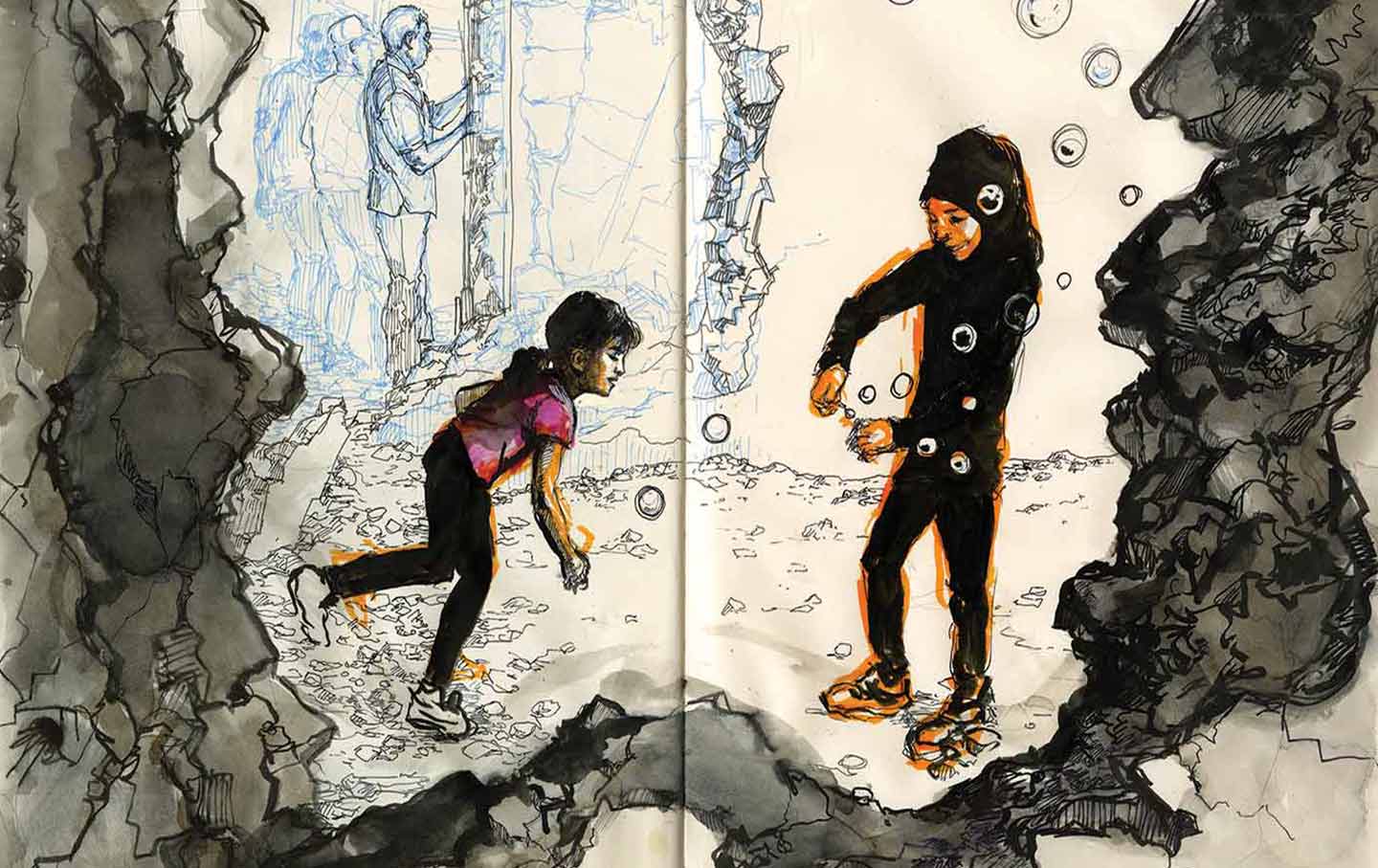

Franz Kafka and his dog.

Franz Kafka’s Best Friend

Kafka’s late story about a philosopher dog, like most of his stories about animals, is really about our lost humanity.

Slavoj Žižek had me at the title of his 1992 book Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Lacan (But Were Afraid to Ask Hitchcock). The words were a siren call to those of us who fear that vast essential insight lies locked in texts with which we simply don’t play well. It’s not that I’m not interested in Lacan’s writings, but rather that pleasure, of some variety, is always at the wheel of how I read. Books need to contain, ideally, at least some combination of the things I enjoy: narrative, imagery, gossip, puns, the whisper of the vicarious. I can persist with prose that restricts or denies me these pleasures, and often do, in pursuit of other rewards. Yet there are times when I feel truly helpless with theoretical concepts that have been left ungrounded in tangible example or evocative metaphor. Even if I forgo pleasure and fight my way through such material, there’s scant uptake.

Books in review

How to Research Like a Dog: Kafka’s New Science

Buy this bookIn such cases, I’m reliant instead on paraphrase or analogy—in the case of Žižek’s book, an introduction to Lacanian theory by way of The Birds and Vertigo. It’s a win-win-win: I’m refreshed in my fascination with films I’ve known for 50 years; I’m vitaminized with Lacanian epiphany; and I discover a nutty new friend in the provocateur Žižek, whose own thoughts are accessible to me only about half the time (elsewhere I may find myself hunting for an accessible paraphrase of Žižek). All my life, I’ve known that certain strains of inquiry—philosophy and political theory and psychoanalysis—had the potential to give names to my inchoate feelings and courage to my efforts to live honorably in the human herd. But how to unlock the treasure? For every thinker in whom I found readerly oxygen (Nietzsche is truly a gas), there were others (hello, Heidegger) whose abstractions were, for me, like meeting a concrete wall: impenetrable at any speed.

So, over the years, I’ve become something of a connoisseur of books like Žižek’s, or others like David Rothenberg’s The Possibility of Reddish Green, which explores Ludwig Wittgenstein’s philosophy through works to which I already relate, such as Thomas Bernhard novels and Chris Marker films. These bring me as close as I’ll probably ever get. I can hear Wittgensteinians screaming at me now that their boy is wonderful to read; to them I say simply, “For you.” In a life where, at 60, I haven’t tackled Nabokov’s Ada and still want to reread Christina Stead’s The Man Who Loved Children, I probably won’t be climbing over that wall.

This embarrassing disclosure of my reliance on paraphrase reminds me that Pierre Bayard recommends it as a positive intellectual program in his book How to Talk About Books You Haven’t Read. At least I think he does; Bayard’s book, alas and ironically, is itself one I haven’t read. (I think he’d forgive me.) When I’m in the right mood, I can ponder Freud with genuine pleasure; Marx, not so much, though I have persevered. Yet it is forever the case that I’ve familiarized myself with both Freud and Marx more through inference and interpretation, through Adam Phillips and Mari Ruti and David Graeber and T.J. Clark, than directly. Perhaps this is natural: English literature begins with Chaucer appropriating The Oresteia. It’s all paraphrase anyway.

When it comes to Kafka, Deborah Eisenberg observed earlier this year in The New York Review of Books, “there seem to be a lot of people who approach (or avoid) Kafka’s fiction in anticipation of something somber, cryptic, too abstruse to enjoy.” This is “unfortunate,” she continues, “because the fiction is mesmerizing, unendingly rewarding, and often wildly funny.” In this case, unlike with Wittgenstein, I endorse this advocacy for the original. Ever since I discovered Kafka as a teenage prose-omnivore who mistakenly thought The Trial was a dystopian thriller (or maybe I wasn’t mistaken?), I have read him, mimicked him, and assigned him in classrooms. To Eisenberg’s perfect adjective—“mesmerizing”—I would add that Kafka is also surprisingly, extensively earthy. His work, though often top-heavy with paradox and conceptual brio, is rooted in the squishy, itchy, sleepy, flirty, flighty feelings in the body, and never more so than when he is writing about animals. And he is often writing about animals. We all know the cockroach, but there is also the ape, the mouse, the mole, the leopards, and “Investigations of a Dog.”

Loving Kafka, one would think, is enough: no need for paraphrase, merely dive in. But for me, Kafka is the paradigmatic example of a writer we read, even devour, and return to with joy, yet still hunger to see interpreted by others. And luckily (for me, anyway), Kafka is one of the most interpreted, annotated, and biographed writers, or possibly even humans, who ever came down the pike.

Aaron Schuster’s How to Research Like a Dog: Kafka’s New Science, a book squarely in the charismatic-paraphrase tradition of Žižek, is a lengthy investigation of Kafka’s dog story. A terrifically erudite and accessible ramble through Kafka, Lacan, Freud, and Beckett, among others, the book may also persuade you, as it did me, that “Investigations of a Dog”—which was written near the end of Kafka’s life, just as he was abandoning The Castle, and is a somewhat sidelined text (Walter Benjamin admitted that it baffled him)—is as rewarding an object of devotion as anything Kafka ever wrote. Beyond all this, Schuster’s book, along with Kafka’s story, may deepen one’s fascination with and delight in dogs themselves—partly by helping us notice how much Kafka was also noticing dogs themselves, rather than merely the idea of them.

In Marlen Haushofer’s novel The Wall, a woman who has been removed from all human companionship muses on her central surviving relationship, with a dog named Lynx:

It was almost shaming that being with me made him so happy. I don’t think that grown animals living wild are happy or even content. Living with people must have awoken this capacity in the dog. I’d like to know why we have this narcotic effect on dogs…. Of course there was never anything special about me; Lynx was, like all dogs, simply addicted to people.

Philosophers, such as Thomas Nagel in his famous essay “What Is It Like to Be a Bat?” and Giorgio Agamben in The Open, have tended to fasten on the animal as an emblem of the unknowable—the proximate “other” whose ineluctable difference unnerves us, throwing us into an awareness of our existential condition. But the domesticated dog, as Haushofer reminds us, offers us another kind of conundrum: It is a creature entwined in human life to such a degree that it has become estranged from its own kind, even while remaining in touch, helplessly, with its past nature.

Unsurprisingly, these are the qualities that fascinated Kafka in his “Investigations”; his dog, like his characters in general, suffers a sense of cosmic displacement from some right manner of being. Kafka’s unnamed dog narrator studies his own kind, who present a panoply of accommodations to this alienated condition, while never managing any accommodation of his own.

The failure to reach an accord with his reality makes the dog much like Kafka’s paradigmatic protagonists—think of K., the Hunger Artist, and Gregor Samsa. Yet what sets the dog apart from these others, and sets Schuster off on his own remarkable avenue of research, is the canine’s tendency not to center his own suffering and complaint, or his moral or emotional crisis, but instead to cast himself in a deliberate and positive role as a searcher—a quixotic knight of ignorance. “The nascent philosopher,” Schuster writes, “finds his spark of enjoyment in asking questions and not getting responses—this failed interrogation is where he really comes alive, where his innermost nature gets activated, energized. His subsequent life will be organized around the posing of questions and the nonreception of answers.”

Spoiler alert: Kafka’s story turns on a joke, one hiding in plain sight. It’s an easy joke once you get it, but Kafka being Kafka, and with his reputation for being abstruse, it often takes several readings to believe in its simplicity (I wonder if Walter Benjamin missed it). The joke is that Kafka’s philosopher dog, due to some unexplained anthropomorphic blind spot, can’t see the human beings who dominate the world that dogs inhabit. Lapdogs therefore appear to him as floating dogs; dogs in a circus appear enchanted by the desire to perform. Most crucially, food seems to appear out of nowhere, according to ritual actions on the part of the dogs that the narrator can index but never decipher.

Of course, this couldn’t be more “Kafkaesque.” As in The Castle and The Trial, every character’s life is distorted by the presence of an omnipresent and gnomic form of power that also possibly doesn’t exist. Yet since we readers are humans—living examples of the puzzle piece that could explain (well, partly) the behavior of the dogs whose priorities and outlook the narrator dog finds so mysterious—the story makes a gentler allegory of the comedy of inquiry than perhaps anything else in Kafka. What if our lives turned on the same joke? What if the great mystery always turned out to be our own obtuseness, the blot in our sight that we just can’t see around? This—I know this from paraphrase—is a strongly Lacanian suggestion.

Schuster’s book is thrilling for its fleetness of reference and insight, as well as its readiness with biographical anecdotes. These can range far afield as well as close to home and concern not only the legendarily quirky Kafka but also the severest of psychoanalytic theorists (and their pets). In one fascinating section, Schuster reminds us that “like Freud, Lacan also had a pet dog, a boxer he named Justine as a tongue-in-cheek homage to the novel by the Divine Marquis—a Sadeian dog for the French psychoanalyst,” and one who, in Lacan’s account, “can talk…she has the gift of speech, but ‘this does not mean that she possesses language totally.’”

Justine’s partial possession of language, Schuster notes, is in some ways linked to Kafka’s dog and is characterized by two traits. First, unlike “many human beings,” she speaks “only in those moments when she needs to speak”—to convey her emotional states or respond to environmental stimuli, such as, for example, the presence of Lacan. Second, when she speaks, “she identifies [Lacan] accurately—unlike his patients in analysis, for whom Lacan may very well be someone else…. The dog relates to others as little others, partners in dialogue and communication, but the other is never taken for an Other.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Ah, the capitalized Other: If you’ve heard the first thing about Lacan (which I have, thanks to Žižek!), you know that the “big Other” isn’t someone we can meet, but precisely the omnipresent power of social injunction that intervenes between us and direct experience. How perfectly does all this lead us back to Kafka’s fictional investigating dog, for he too is a creature to whom the big Other—in this case, actual humans—is invisible, despite their influence being traceable everywhere.

In another particularly arresting sequence of interpretation and extrapolation, Schuster moves deftly between the notion of “office comedy,” Foucault, Duras, and the suggestion that Flaubert’s notoriously wearisome comic epic of ignorant scholarship, Bouvard and Pécuchet, anticipates Google and ChatGTP:

If Flaubert heroically, and madly, realizes the Tower of Babel of science with his universal encyclopedia, Kafka, in a no less rigorous way, short-circuits the whole edifice in a stroke. We are no longer dealing with the dispersion of languages, the seemingly endless babbling of discourse, but with a hole in language. Hence the need for a new myth, or a subversive twist on the old one: the pit of Babel.

For me, the Flaubert reference in particular happened to light up a dormant piece of circuitry in my brain. Bouvard and Pécuchet has sat unread on my shelf for more than 30 years. Now, thanks to Schuster, I suddenly considered that book as an ironic talisman of the way our tiny shares of understanding are swarmed on every side by the millions of books we’ve never even begun to attempt to read—by their opacity, their implication, their promise.

My life’s own most deliberate and proud expedition—that as a reader—makes me, in the end, only very much like Kafka’s dog. Yet, high on borrowed confidence from Schuster’s book, drunk on the delirium of his foray, I find myself vowing to finally read the Flaubert. Should I succeed, who knows what might happen next? I must read Lacan. I can’t read Lacan. I’ll read Lacan.

More from The Nation

The Riotous Worlds of Thomas Pynchon The Riotous Worlds of Thomas Pynchon

From “The Crying Lot of 49” to his latest noirs, the American novelist has always proceeded along a track strangely parallel to our own.

Letters From the March 2026 Issue Letters From the March 2026 Issue

Basement books… Kate Wagner replies… Reading Pirandello (online only)… Gus O’Connor replies…

Molly Crabapple's Time Capsule of Resistance Molly Crabapple's Time Capsule of Resistance

A new set of note cards by the artist and writer documents scenes of protest in the 21st century.

The Exposure Therapy of “A Private Life” The Exposure Therapy of “A Private Life”

In her new film, Jodie Foster transforms into a therapist-detective.

How to Build a Moon Garden When the News Is All Horror How to Build a Moon Garden When the News Is All Horror