Helen Garner’s Alienating Domesticity

In her novel The Children’s Bach, the Australian writer conjures a relentless portrait of the comforts and restrictions of family life.

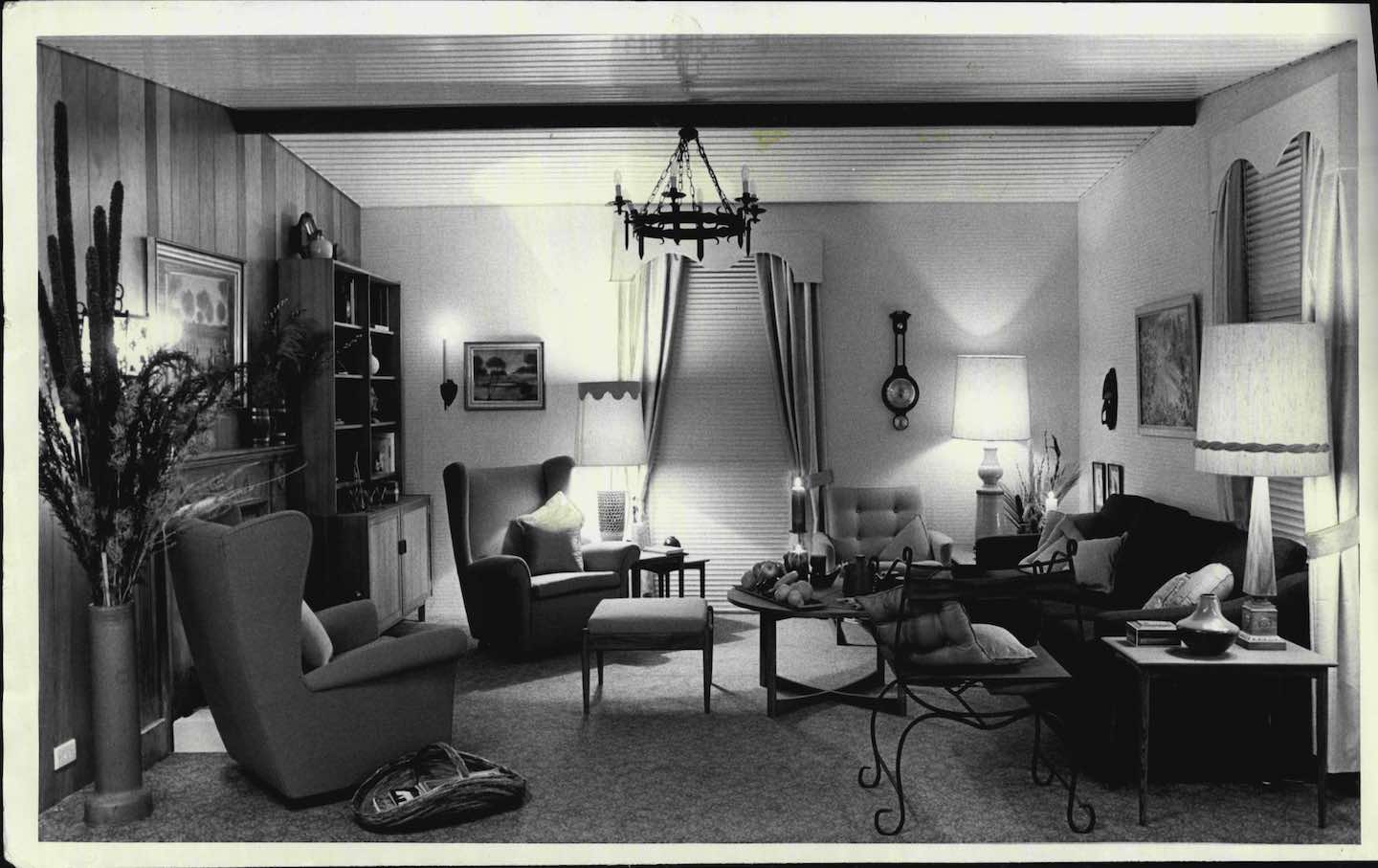

A model home in Sydney, 1968.

(Photo by Ronald Leslie Stewart/Fairfax Media via Getty Images).The houses were full of what she described as “disciplined hippies.” There were single mothers with small kids, cooperative men, and boyfriends who’d overstayed their welcome. The tasks were divvied up equally. In the summertime, they would bundle up their towels and goggles and bike to the local pool. Under these communal arrangements, separated from her first husband and caring for their young child, the Australian writer Helen Garner wrote her debut novel, Monkey Grip. For a year, she sat at Melbourne’s State Library, moving around bits of her diary to produce what would become the book—a slanted vision of inner-city bohemia, about a young mother living in a Melbourne sharehouse, desperately in love with a scrawny heroin addict.

Books in review

The Children’s Bach

Buy this bookExperiments in caregiving and living with others (as well as the single mother’s support benefit she received from the government) made Garner’s early writing possible. They would also become the pervasive subjects of nearly all of her work, a mass of novels, journalism, screenplays, diaries, and essays. Seclusion rarely registers in Garner’s books: She is invested in the muck of collective life, with all of its brutalities, ironies, and ambivalences. In her fiction, these relations play out in the home, a place elastic and unstable, where people are constantly being brought in or shoved out. A couple is never just a couple; there are kids and sisters and friends and former partners to look after. Even when she stopped writing about the interchangeable intimacies of the sharehouse, Garner examined relationships and obligations in flux, the strange new clusters that could form under such mercurial circumstances.

It’s as if the sticky fingerprints of the era’s unrealized promises of freedom, sex, and reconfigured families could never fully be scrubbed off. They are all over The Children’s Bach, Garner’s second and best novel, in which the sedate joys and monotonous order of family life are shaken and, eventually, fall to pieces. With its slippery form and flickering perspectives, the novel offers its own kind of disturbance to the conventions of the domestic drama. The Children’s Bach inverts Goethe’s famous description of chamber music as “rational people conversing”: In Garner’s hands, it becomes a clamor of voices, images, and instruments that prove to be unreliable and full of doubt. Love and understanding are fought for anyway.

First published in Australia in 1984, The Children’s Bach opens with a photograph of Alfred Lord Tennyson and his family, plastered up on a kitchen wall, blotted in grease and in constant threat of falling down. The kitchen is presided over by Dexter and Athena Fox, who live in a ramshackle but sweet suburban Melbourne home with their two young sons: the booming and chatty Arthur, and Billy, an autistic boy prone to fits, who sings but does not speak.

The couple love each other, but their lives are airless and unvarying, passion smothered under the snug embrace of domesticity. Dexter is relentlessly joyful, roaring arias from Don Giovanni at the top of his lungs and offering old-fashioned polemics (“I hate modern life…. Modern American manners”). Athena is more searching, and a little sad. Her free time is spent at home, teaching herself the piano. She is not good, and her fumblings at the keyboard mostly fill her with shame—but then, on rare occasions, a glimmer of musicality appears: “Even under her ignorant fingers those simple chords rang like a shout of triumph, and she would run to stick her hot face out the window.”

The couple’s shared, sealed-off existence is pierced when Dexter runs into an old college friend at the airport: Elizabeth, a cynic and occasional klepto. Unlike Dexter, who worships the past (“he used it to knit meaning into the mess of everything”), Elizabeth would prefer to shed its humiliating residues and forgo nostalgia. Her mother has just died, and now she must care for Vicki, her 17-year-old sister, who has abandoned her schooling overseas.

The sisters, bound together by duty, infiltrate the Foxes’ lives, where responsibility to one another takes a different shape: compact but crumpled, triviality lost in the folds of endless labor. Then another pair edges in. There is Philip, Elizabeth’s boyfriend, a charming, faithless musician, and his daughter, a tween cellist named Poppy. The tenuous divide between the nuclear family and the “rough sexual world that lies outside” begins to cave in.

At 160 pages, this slender novel has been whittled down to a point, with edges that are sharp and wounding. Garner envelops her characters in secrecy, only to swerve into startling disclosure, the lashings of inner ugliness. What astonishes, even now, is her nonjudgmental attitude. Her characters are given free rein to think and act viciously, without getting caught in the net of pithy moralism. Abraded compassion and empathy’s coarse limits bristle on the page. In one scene, Vicki takes Billy for a walk, and in a “rapture of disgust” she imagines pushing him under a truck. Dragging the boy back to the Foxes’ home, she asks Athena if she has ever had the same sudden flare of violent fantasy. “Of course,” Athena says, “hundreds of times.” This is quintessential Garner: a renunciation of the belief in love and caretaking’s innate benevolence, and an attempt to expel shame’s stultifying effects.

Her characters cast enough judgment on one another anyway. Athena suffers the most: Her status as a mother caring for a child with a disability makes her ripe for others’ misperceptions; she is held up, with a kind of fetishistic fascination, as a paragon of humility. “Contained, without needs, never restless,” thinks Vicki, who is completely enamored with the Foxes’ household. In the eyes of her observers, Athena cooks and cleans with a type of easy grace, filling her home with the meek sounds of her elemental music.

No one wonders if this gracious nature might be the product of necessity. When Athena begins to stray from the home and take extended walks with Phillip, Garner provides one of the novel’s most crushing passages, pinning down what women must surrender in order to make even the most casual affair viable:

Like most women she possessed, for good or ill, a limitless faculty for adjustment. She felt him give; she let herself melt, drift, take the measure of his new position, and harden again into an appropriate configuration. There was something to be got here, if only she could…

Helen Garner was born in 1942. She is an omnipresent figure in Australian letters, widely adored but also marginally despised (some have never forgiven her for The First Stone, her defensive—but ultimately prescient—examination of a sexual harassment case at a Melbourne university, published in 1995). She is often thought of as a gritty realist, someone who lays things out as they truly are, hideous and unadorned. Monkey Grip was a revelation partly because it refused to dress up or explain Australian urban life in the hope of courting overseas acclaim.

Garner’s reputation for a certain starkness grew when she turned from fiction to nonfiction, writing primarily about the pragmatism of the law in buffering against the confounding, cruel depths of human behavior. But this mantle has often obscured the psychoanalytic bent of her writing. The domestic novel, in modern Australian literature, often coincides with a prose style that is direct and spare, in opposition to the serpentine or meandering. While Garner is fond of tight sentences and a compression of form, she is not austere. In The Children’s Bach, she cuts a path to the truth of experience through abstraction: her willful omissions, her nonlinearity, her ambivalence toward introductions or context or clear motives. Dreams and fantasies periodically crash into the novel’s everyday action and subsume its sentences. Apart from Philip’s artistic toils, we learn nothing of the characters’ day jobs (thank God). These gaps and opacities do not fog up her narrative but manage to engender the opposite—a quivering lucidity.

For The Children’s Bach is not a novel of destinations. With its stream of images, reading it feels like looping around a city on a train, looking out the window: There is distance between yourself and what you see outside. The scenes are small and mostly contained—some that come into focus, others that whip past and blur. In this way, Garner makes visible the rough assemblage of existence, the stitches that fasten together the seemingly disparate moments of a day.

But what an assemblage! There is the noise of off-key, communal singing and of soup being sloppily served out of a pot. In the stinking heat, mattresses are thrown outside and slept on during the night. There is a back door, left ajar, open to practically anyone. Underneath these pleasures rumble the novel’s central questions: How is the comfort of a family sustained without mutating into captivity? Does true intimacy mean that individual sovereignty must always be mangled? In this novel, Garner doesn’t try to imagine a solution (her recently published diaries and essays, meanwhile, come to a more certain conclusion: that romantic cohabitation, full of transient bliss and emotional terror, is unbearable). Rather, her attention turns to those who show up to plug a hole, understudies in a role they are ill-prepared for. Then again, when is mastery over devotion and care ever attainable? Like Athena plonking her fingers on the piano, a certain sloppiness is a given, and amateurism is forever.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →When the moment of fracture comes, it comes quietly. Philip has work in Sydney, so Athena follows, hopping into a cab while a wordless Dexter watches. She’s a tourist in the city, but also a guest in the world of the frivolous and sexually free. She was “half-dead” in the family home, but in this new formation, she is also a kind of ghost, being led by her new lover’s whims. “Everything was his idea: things he proposed they did, and he paid. He knew where places were and how to get there. He showed her: taxis, a rented Commodore to the ocean in the early evening.” The solitary agency of her daydreams has yet to put in an appearance.

As Athena waits around for Phillip, Garner describes the traps that are laid even in the most liberatory of romances, how new alienations and obligations sprout in the absence of old ones. Athena is still bending herself to meet the terms of others. As Garner reminds us, all types of love—and even lust, for that matter—arrive with their own set of losses and dislocations.

But this dislocation does not last. Swiftly, Athena leaves Philip and returns home. She scrubs the filthy house and waits for her family to show up. But The Children’s Bach does not end so much as it imagines an ongoingness beyond the narrative’s confines. The fragments loosen and the already-present gaps widen. Instead of a conclusion, or a rupture, we are offered fleeting images, thought up by Athena, flung across the page:

and the clothes on the line will dry into stiff shapes which loosen when touched,

and someone will put the kettle on,

and from one day to the next Poppy will stop holding Philip’s hand: he will drop his right hand to her left so she can take it, but nothing will happen, and when he looks down she will be standing there beside him, watching for a gap in the traffic, and she will not hold his hand any more, and she never will again,

and Dexter will sit on the edge of the bed to do up his sandals, and Athena will creep over to him and put her head on his knee, and he will take her head in his hands and stroke it with a firm touch,

and the tea will go purling into the cup,

When the novel was originally published, some thought Garner had lapsed into conservatism by reuniting Athena with her family. But her refusal to consolidate an ending suggests something more fluid and true. This free-form torrent, eluding full stops, better reflects the complicated trajectory of desire: how it explodes and disturbs narrative, consumes and then retreats, and just when we think it’s all over, drifts back into our consciousness in scraps. As Garner wrote in her diary while in the midst of working on The Children’s Bach, “I like to leave the reader with one leg hanging over the edge—like E.M. Forster: ‘but her voice floated out, to swell the night’s uneasiness.’”

Thank you for reading The Nation

We hope you enjoyed the story you just read, just one of the many incisive, deeply-reported articles we publish daily. Now more than ever, we need fearless journalism that shifts the needle on important issues, uncovers malfeasance and corruption, and uplifts voices and perspectives that often go unheard in mainstream media.

Throughout this critical election year and a time of media austerity and renewed campus activism and rising labor organizing, independent journalism that gets to the heart of the matter is more critical than ever before. Donate right now and help us hold the powerful accountable, shine a light on issues that would otherwise be swept under the rug, and build a more just and equitable future.

For nearly 160 years, The Nation has stood for truth, justice, and moral clarity. As a reader-supported publication, we are not beholden to the whims of advertisers or a corporate owner. But it does take financial resources to report on stories that may take weeks or months to properly investigate, thoroughly edit and fact-check articles, and get our stories into the hands of readers.

Donate today and stand with us for a better future. Thank you for being a supporter of independent journalism.

More from The Nation

The Rolling Stones Haven’t Missed a Beat The Rolling Stones Haven’t Missed a Beat

The world's greatest rock and roll band is on the road again. This time, they’ve got a new drummer.

Venita Blackburn’s Stages of Grief Venita Blackburn’s Stages of Grief

In Dead in Long Beach, California, the novelist looks at how integral lying is to any story we tell about death.

Clarice Lispector’s Cosmology Clarice Lispector’s Cosmology

To understand the philosophical dimensions of her fiction you must read her 1961 novel The Apple in the Dark.

The Cruel Genius of Robert Plunket’s Gay Satires The Cruel Genius of Robert Plunket’s Gay Satires

His 1992 novel Love Junkie might be one of the tragicomic classics of the AIDS era.

The Peculiar Legacy of E.E. Cummings The Peculiar Legacy of E.E. Cummings

Revisiting his first book, The Enormous Room, a reader can get a sense of everything appealing and appalling in his work.

The World’s Problems Explained in One Issue: Electricity The World’s Problems Explained in One Issue: Electricity

Brett Christophers’s account of the market-induced failure to transition to renewables is his latest entry in a series of books demystifying a multi-pronged global crisis.