Capitalism’s Toxic Nature

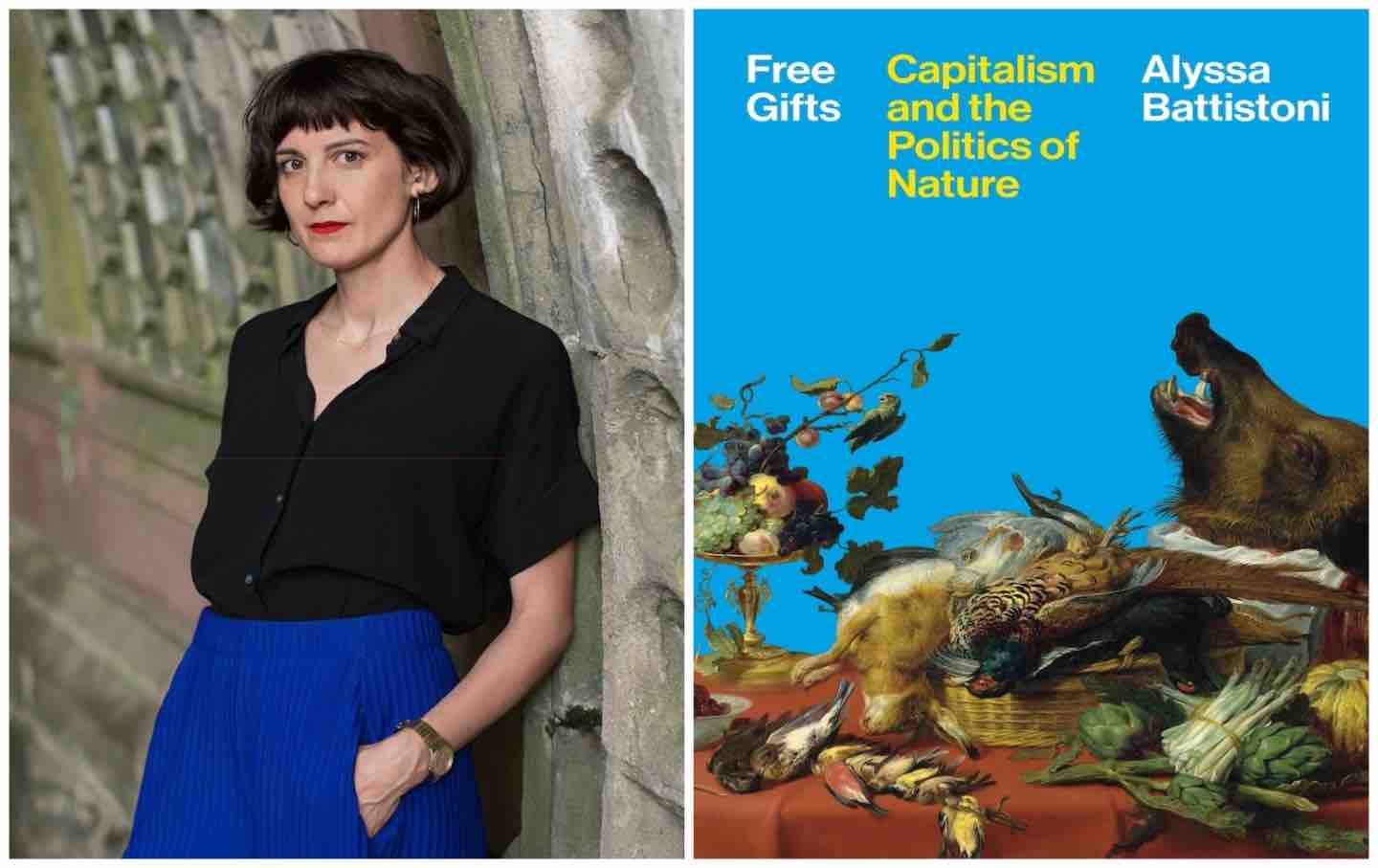

A conversation with Alyssa Battistoni about the essential and contradictory nature of capitalism to the environment and her new book Free Gifts: Capitalism and the Politics of Nature.

The voluminous literature devoted to examining the relationship between capitalism and environmental degradation makes it rather difficult to have something original to say. But in her new book, Free Gifts: Capitalism and the Politics of Nature, the political theorist Alyssa Battistoni does exactly this by pinpointing the exact reasons for capitalism’s persistent failure to value nonhuman nature, and what this means for politics as well as for our collective future on this planet.

Inspired by Marxist thought, Battisoni argues that the problem of climate change is rooted in the manner in which capitalism systematically treats nature as a “free gift.” By this she means that in a capitalist society nature is materially useful but is “something that can be taken without payment or replenishing” and therefore tends not to appear in exchange. How, for instance, do we make sense of the contradiction that exists between how brutal and violent human beings treat the natural world despite the fact that doing so endangers their everyday lives? In other words, why does capitalism fail to value nature’s free gifts?

The Nation spoke with Battisoni about this very contradiction, why it’s inherent to capitalism, and what can be done about it. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

—Daniel Steinmetz-Jenkins

Daniel Steinmetz-Jenkins: Your book proposes what you call a “politics of nature” Can you give us a fuller definition of this politics? How do you conceive of the relationship between politics and the natural world?

Alyssa Battistoni: In colloquial political life, nature is usually associated with what we think of as environmentalism, and treated as an issue area that you can care about or not. In political thought more broadly, though, nature has often been understood as something that exists beyond politics altogether. Political theorists, for instance, often write about the “state of nature” and human nature, but they rarely address nonhuman nature, which is taken for granted as the passive, seemingly unchangeable backdrop against which the drama of human action takes place. But climate change has really challenged this way of thinking about nature: It’s clear that human activity has transformed our planet itself at an atmospheric and even geological level, and that those transformations will have major effects on social and political life. Some have argued that we need to rethink our most basic political concepts, from freedom to democracy to responsibility, to account for the force of the natural world.

In my view, what climate change reveals is not a drastic change in the relationship between nature and politics, but rather that nature has always been part of politics and vice versa. The decisions we make about how to organize our lives together always have implications for how we organize the more-than-human world in which we live. In other words, we can’t just treat “environmental politics” as a separate set of issues or ideas; instead we need to think about how nature pertains to all kinds of political questions. The warming of the planet will have implications for all kinds of politics: conflict, migration, diplomacy, trade.

DSJ: You state the following: “Nature is a free gift by default.” What do you mean by this?

AB: The idea of the free gift isn’t mine: it comes from classical political economy and Marx’s critique of it. Classical political economists writing in the 18th and 19th centuries, from David Ricardo to Jean-Baptiste Say, described nature’s contributions to production—everything from the fertility of the soil to the power of the wind—as free gifts. Marx in turn criticized them for failing to recognize that in a capitalist society, nature gives only to capital: It’s those who own the means of production who benefit from the productivity of nature and capture the wealth it creates. The concept of the free gift itself, however, is stranger and more significant than has typically been recognized.

It’s common in Western and non-Western philosophy to think of nature as a gift, often from God or some kind of Creator. The idea that nature is a free gift, though, is different—and peculiar. It’s odd, after all, to describe a gift as free: Gifts are, by definition, not bought and sold in the manner of commodities, so on the one hand it seems redundant to even describe them as free. Yet on the other hand, gifts are often understood to incur obligations and create ongoing relationships: In many societies they are fundamentally reciprocal, such that the idea of a free gift negates the basic premise. In both cases, the gift is usually understood as a kind of relationship that’s radically different to the commodity, and often as something that stands outside of capitalism altogether.

But the free gift of nature isn’t outside of capitalism at all. To the contrary, to say that nature is a free gift is to define it in terms of price, or its absence: In other words, to locate nature’s gifts within a system that’s generally organized by the exchange of commodities on the market, where most things—including human labor—must be acquired through monetary payment, and in which production is organized not simply for use but for the accumulation of abstract value. So the book’s core argument is that capitalism fundamentally and systematically treats nature as a free gift: as a source of useful things that we don’t have to pay for or reciprocate.

I argue that capitalism’s system of value constitutes nature in opposition to waged human labor: The instigation of the wage relation as a core relation between human beings renders all of nonhuman nature constitutively wageless, and thus as other-than human labor. Whereas human labor has to be acquired via the payment of a wage, in other words, nonhuman nature is available without payment—at least by default. I say by default, because in practice, many kinds of nature are bought and sold. Property is important because it is the only way that nature can be represented in such a system—though of course the payments aren’t made to nature itself but to their human owners. To say that the free gift is a capitalist social form doesn’t mean that all kinds of nature are literally free; instead, it describes how nature typically appears within capitalist societies.

DSJ: What would you say to those critics who see Marx as touting a disastrous form of humanism, which embodied the anthropocentric spirit of the modern age obsessed with the mastery of nature?

AB: Ecological thinkers have often been very critical of Marx, claiming that he wanted to dominate nature for human flourishing. And there certainly are places where Marx does seem to endorse such a view: The Communist Manifesto, for instance, describes the bourgeoisie’s “subjection of nature’s forces to Man” with awe. On the other hand, eco-Marxists like John Bellamy Foster and Kohei Saito have shown that Marx actually was concerned with what we’d now think of as ecological questions: for instance, with the erosion of soil fertility by capitalist agriculture. But I think that whether or not Marx himself celebrated the domination of nature is beside the point. Capital is a critique of political economy, and a critique of capitalism, not a positive program. So the book argues that it’s actually capitalism that is a humanism: that it’s capitalism that draws a sharp distinction between human labor and nonhuman nature.

Similarly, Marx is often thought to celebrate labor as a way that human consciousness extends itself into the world. And again, there is evidence for this, especially in his early writings. But as I argue, what’s more important is the way that certain human qualities take on inordinate significance within capitalism—which does not mean that they reflect the exceptional or superior quality of human beings per se. Human consciousness makes possible the basic social relation of class within capitalism: It enables the separation of individual beings from their means of subsistence, and the direction of some people’s labor by others. Human beings are also radically underdetermined by nature: We have a set of basic capacities given by biology, but those capacities can be utilized in radically different ways. In capitalist societies, one group of people instructs another in how to use those capacities. The exchange of labor for a wage is also rooted in distinctively human capacities for symbolic reasoning and abstract thought; nonhumans can be put to work, but they can’t, as far as we know, separate out their time. That means that capitalism is organized around a form of value from which nonhumans are fundamentally excluded. Marx is diagnosing this, in my view—not necessarily endorsing it.

Marx himself famously said very little about what a post-capitalist society would look like, but I don’t think there’s any reason to think that his tools of analysis preclude us from envisioning and enacting a more ecologically conscious and sustainable form of society, whether we call it eco-socialism or “degrowth communism,” per Saito. The key point is that a post-capitalist society would be organized around use value rather than exchange value, and around meeting concrete needs—which could include nonhuman as well as human needs—rather than around the criteria of profitability and value accumulation which dominate capitalist societies.

DSJ: You write that the “freedom to choose is worth defending” while acknowledging that such rhetoric is associated with the neoliberal Milton Friedman’s full-throated defense of capitalism. Indeed, you even say that his fellow neoliberal traveller, Friedrich Hayek articulated a conception of freedom that is “particularly challenging…to refute.” More generally, you state that these proponents of the freedom to choose are not wrong to “emphasize the importance of deciding what we think is most important.” You are a leftist thinker. What is to be gleaned from engaging with these neoliberals?

AB: The book engages a great deal with thinkers I disagree with, including many economists we’d usually describe as neoliberal. This is in part because the ideas that economists working in those traditions have developed—like carbon markets or natural capital—have been at the center of climate and environmental politics for a long time, and it’s important to understand those ideas in order to develop a rigorous critique of and response to them. But it’s also because I think their theories usually do describe something about how capitalism works, even if their analyses tend to stay at a surface level. This is why Marx reads the classical political economists he critiques, after all.

I engage with Hayek and Friedman in particular for a few reasons. One is simply that the idea of the freedom to choose in the market that they’ve advanced has been extremely influential in the late 20th century, and has come to quite significantly inform quotidian ideas of both freedom and choice—both of which are frequently equated with consumer choice. Yet as influential as this idea has been, it has received surprisingly little attention from the left. The freedom to choose is derided as empty or misguided—but it is too quickly dismissed rather than truly engaged. Although many critics of capitalism have sought to reclaim freedom in recent years, meanwhile, they’ve typically criticized the domination of labor by capital or the unfreedom of class society than targeting market freedom per se. But in my view, we need to have a stronger response to the likes of Hayek and Friedman on these points, and a more granular account of why the market makes us unfree. That’s what I try to develop.

What’s more, I do find something compelling in Hayek’s account of the freedom to choose our values. Hayek writes quite powerfully sometimes about the freedom to build one’s life and the responsibility that comes with that. He is, of course, extremely critical of the assumption that states are beneficent agents serving a known common good—but while I don’t share his anti-statism, I do think we should be skeptical of appeals to absolute values handed down by God, derived from nature, or even embedded in existing social practices. We do need to reflect on the values we’ve inherited and decide what matters to us, and we have to commit ourselves to those values in action in a finite world.… The problem with Hayek, I argue, is not that he defends the freedom to choose our values, or even that he holds us responsible for those choices, but that he identifies the market as the site in which we can and in fact must exercise this freedom. In fact, I show, markets within capitalist societies ultimately thwart this pursuit.

DSJ: When putting forward your own constructive view of freedom you interestingly find inspiration in the thoughts of French existential thinkers Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre. What is it regarding their thinking about value that you find valuable for a politics of nature?

AB: The existentialism of Beauvoir and Sartre is admittedly a counterintuitive choice for a politics of nature, because as Sartre himself famously put it, existentialism is a humanism. One of its key premises is that human beings make our own lives. ButI find existentialism’s anti-foundational view of value very useful in thinking about the politics of nature. Ecological critiques of capitalism have often been deeply moralistic, and are frequently founded on claims about the inherent value of nature. But I think we need to approach nature with more skepticism: Nature is a tricky category, and appeals to nature are never liberatory. Sartre and Beauvoir insist that nature doesn’t give us values; we have to define them for ourselves. This may sound anthropocentric—but I think it’s true.

Here, too, I think it’s crucial to separate out anthropocentrism or humanism from charges of Prometheanism and the “mastery of nature.” Human beings do have distinctive qualities and abilities, and political decision-making is one of them—but that doesn’t mean the content of our decisions always has to center or prioritize human interests above all else. In other words, we can recognize that we, as human beings, have a distinctive ability to make conscious choices about how we live in the world, and thus a distinctive responsibility to reflect on how we do so, without thereby saying that we can remake the world entirely as we please or should remake it to satisfy human interests alone. Value is an unavoidably human concept—which doesn’t mean that only human beings are valuable or have value. We absolutely can choose to value forms of life that are not useful to us, because we think they deserve to exist in their own right—and I personally think we should! But we should recognize that we are ultimately responsible for doing so.

Existentialism also insists that we also have to take concrete actions that reflect the values we profess to hold. Simply saying that nonhumans have intrinsic value beyond human judgment, as many thinkers of ecological ethics have claimed, doesn’t get us very far. We have to realize our values in the world. And this raises difficult questions, since it’s obviously not possible to live without making use of other beings, including living beings, in ways that may be destructive to them. If we say that all of nature has intrinsic value but we still cut down a tree to make a table, or plow a field to grow crops, it’s not clear to me what work the concept of intrinsic value is doing. Intrinsic and instrumental value don’t have to be totally counterposed, of course: We can recognize that things have value beyond their usefulness to us. But again, what exactly follows from such declarations of value isn’t clear; it’s in deciding how to act on them that things get really interesting.

DSJ: Given the Trump presidency and, more generally, the current right-wing state of the world, it is hard to be optimistic—indeed, a kind of political pessimism, if not fatalism, marks the rhetoric of much of the Democratic Party. Is it correct to read your book as a rejection of such fatalism, especially given its defense of a material existentialism which seems to hint at a different future for earthly life?

AB: I certainly think the book is a rejection of fatalism—which is not to say that it’s optimistic! No one who knows much about climate change would be optimistic about our prospects. And yet as pessimistic as we may be, we still have to keep trying to stop emissions and keep temperatures down, since we are going to have to live on this planet one way or another. That’s why I generally don’t find the framing of climate politics in terms of optimism and pessimism very helpful. By contrast, I find Simone de Beauvoir’s concept of ambiguity much more compelling: It seems to me like the only honest way to approach our uncertain future. Ambiguity is central to Beauvoir’s concept of freedom: It describes the condition of being both a material, embodied creature and a conscious mind. Most philosophers, Beauvoir thinks, have tried to resolve this in the direction of material determinism or idealism; instead, she argues, we should embrace our ambiguity. That, in turn, means embracing the challenge of getting individual people, each with their own goals and subjectivities and material situations, to act collectively.

Freedom, then, is not a panacea for Beauvoir. To the contrary, she emphasizes that freedom does not guarantee any kind of solution to the problems we face. Freedom is a process, not a destination: It means that we have to continuously reevaluate our projects and values in light of what we learn about the world, and reassess how we might realize them in action with others who are also, always, free to choose something different. Freedom, in other words, is resolutely open-ended: As Beauvoir puts it in her short book The Ethics of Ambiguity, “if it could be defined by the final point for which it aims, it would no longer be freedom.” This perspective may not be particularly reassuring, but I think that’s precisely why it’s important: Rather than pretending that there is a “solution” to the climate crisis, or that we can get back on track to the future of abundance and stability long imagined by the left, we have to recognize that we have changed the planet irrevocably and that we will have to keep making our way in an uncertain and volatile future.

In my view, it also means that there’s never a point where it’s “too late” to do something about climate change—no point when we can succumb to fatalism and give up—because we will always have choices about what we’ll do and how we’ll act, even if those choices are between bad options. And I think they often will be! We will undoubtedly face many difficult decisions as planetary temperatures rise and biospheric conditions deteriorate, but we are in bad faith if we say that we have no choice but to take certain actions—for instance, to harden borders against climate migrants, as the right will no doubt argue we must do.

DSJ: You coauthored in 2019 the manifesto, A Planet to Win: Why We Need a Green New Deal. Talk of a Green New Deal has fallen by the wayside a bit, perhaps due to how far away it seems in light of the Trump presidency. How, though, do some of the ideas of your new book connect to your earlier call for a Green New Deal?

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →AB: Free Gifts is much more theoretical than A Planet to Win; it admittedly doesn’t have much in the way of a political program or policy suggestions. But there are important resonances and through lines between the two.

One of the most basic is the attempt to show how the politics of climate and nature are much more expansive than they are typically taken to be, and look at both from fresh angles. In particular, it’s vital to think about climate politics in relation to political economy. Market solutions have dominated climate politics for decades, but they have failed. It’s crucial to understand why market solutions won’t address the more foundational problem of the free gift of nature—and for that matter, to ask why “market failure” has been the way we think about climate change in the first place. We need to bring more overtly political forms of decision-making and planning to bear on ecosystems rather than leaving them to the whims of capitalist investment and individual consumer choices.

We also need new kinds of climate politics. Climate politics, and environmental politics more generally, have often been seen as distinct from class-based or “material” politics: They are said to be concerned with “post-material” issues like moral values or ways of life rather than “economic” questions like the organization of labor or the distribution of goods. Environmental issues are often thought of as niche rather than mass concerns, and environmental activism is associated with small groups of radicals engaged in direct action—blowing up a pipeline, for instance. But climate and environmental politics are fundamentally rooted in decisions about production and consumption that are relevant to everyone. They demand a genuinely mass form of politics, and require new forms of class struggle.

Finally, freedom is an animating concept in both. We’re often told that addressing climate change will limit our freedom: We won’t be able to drive as much or eat as many burgers. But this wrongly equates freedom to consumption. Freedom, I argue, is really about the ability to determine how to live in ways we find meaningful—which doesn’t mean there are no material constraints at all. In other words, driving a car isn’t freedom; rather, freedom comes in being able to move, to get from one place to another in order to achieve one’s aims, whether that means going to school or visiting a friend or going to the park. So even though the Green New Deal is less of a presence in thenational political conversation, it is very much alive in ideas like Zohran Mamdani’s call for fast and free buses, which would be a way of expanding rather than limiting freedom. Fast and free buses—and better yet, fast and free electric buses—would make it possible for people to go about their lives and do the things that matter to them while generating less traffic and carbon emissions and air pollution and pedestrian deaths, all of which limit freedom in their own right.

Support independent journalism that does not fall in line

Even before February 28, the reasons for Donald Trump’s imploding approval rating were abundantly clear: untrammeled corruption and personal enrichment to the tune of billions of dollars during an affordability crisis, a foreign policy guided only by his own derelict sense of morality, and the deployment of a murderous campaign of occupation, detention, and deportation on American streets.

Now an undeclared, unauthorized, unpopular, and unconstitutional war of aggression against Iran has spread like wildfire through the region and into Europe. A new “forever war”—with an ever-increasing likelihood of American troops on the ground—may very well be upon us.

As we’ve seen over and over, this administration uses lies, misdirection, and attempts to flood the zone to justify its abuses of power at home and abroad. Just as Trump, Marco Rubio, and Pete Hegseth offer erratic and contradictory rationales for the attacks on Iran, the administration is also spreading the lie that the upcoming midterm elections are under threat from noncitizens on voter rolls. When these lies go unchecked, they become the basis for further authoritarian encroachment and war.

In these dark times, independent journalism is uniquely able to uncover the falsehoods that threaten our republic—and civilians around the world—and shine a bright light on the truth.

The Nation’s experienced team of writers, editors, and fact-checkers understands the scale of what we’re up against and the urgency with which we have to act. That’s why we’re publishing critical reporting and analysis of the war on Iran, ICE violence at home, new forms of voter suppression emerging in the courts, and much more.

But this journalism is possible only with your support.

This March, The Nation needs to raise $50,000 to ensure that we have the resources for reporting and analysis that sets the record straight and empowers people of conscience to organize. Will you donate today?

More from The Nation

The Fictitious Capital of HBO’s Industry The Fictitious Capital of HBO’s "Industry"

In the show’s fourth season, everyone has a story to sell and very few are true.

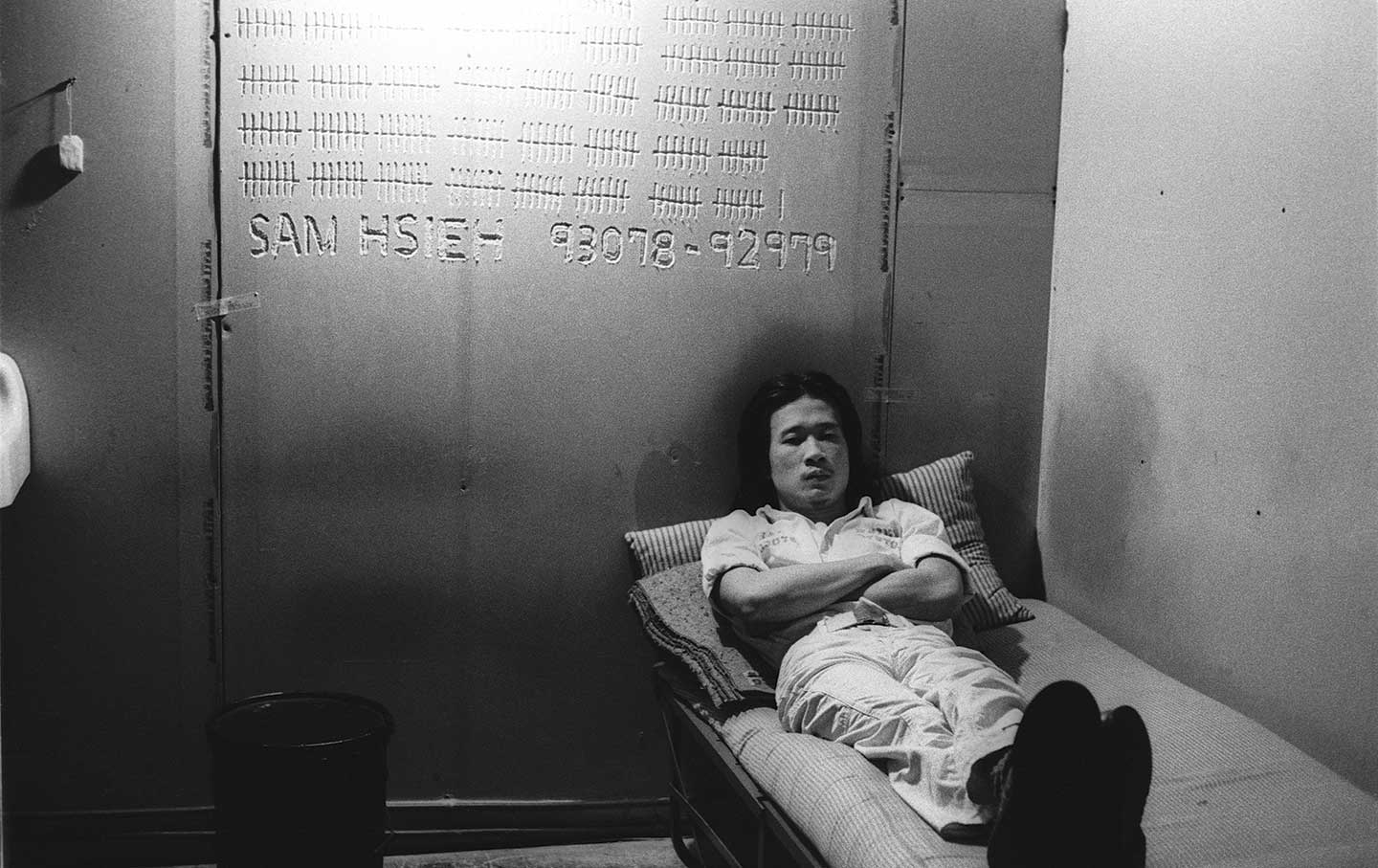

Tehching Hsieh—an “Artist Without Art” Tehching Hsieh—an “Artist Without Art”

In his performances, he questioned whether or not an artwork needed to supply a specific meaning in order to generate a feeling.

George Packer’s Liberal Imagination George Packer’s Liberal Imagination

What happens when liberalism’s crisis is made into a fable?