Seeing Japanese American Heritage Through Ansel Adams’s Lens

A photographer excavates personal history through reconstruction of Adams’s World War II photographs of Japanese Americans interned at the Manzanar Relocation Center.

My great aunt Katherine, a nisei Japanese American from Hawai‘i, and my great uncle Joe, a southern Italian immigrant from Satriano, Calabria, met at the height of World War II in Philadelphia, where they applied for a marriage license on August 22, 1945, shortly after the war ended.

If this story sounds like the American Dream, in certain ways, it was. Their mother tongues were Japanese and Italian—or, more specifically, regional dialects of these languages that their parents spoke—and they fell in love in English, their shared second language, as they acclimated to the local culture of South Philadelphia in the 1940s. At the time of their union, however, interracial marriage was still illegal in more than half of the nation, and they both faced discrimination that was underscored by federal legislation based on ethnic origin, such as the Immigration Act of 1924, which targeted people from East Asia and southern Europe. As newlyweds, they relocated for about a year to the island of O‘ahu to be near my great aunt’s mother and siblings.

On my way to Japan, I arrived to New Year’s Eve fireworks in Honolulu. I had not been to Hawai‘i since 1991 with Katherine and Joe, yet the place continued to feel familiar. As quickly as I had checked into my room, I put on my “rubbah slippahs,” which my aunt had reminded me to bring, and which I wore for my entire stay. The following week, upon arriving in Japan, I learned from my parents that Katherine had passed away. Two weeks earlier I had been at her bedside in Philadelphia, one week ago I had been in Honolulu, and now I was in Japan. Time and place were interconnected and cyclical—something my great aunt always seemed to demonstrate, even in her passing. This approach to life, which she and I shared, and she encouraged, has continued to inform all my work, setting the stage for Born Free and Equal: The Story of Loyal _______-Americans.

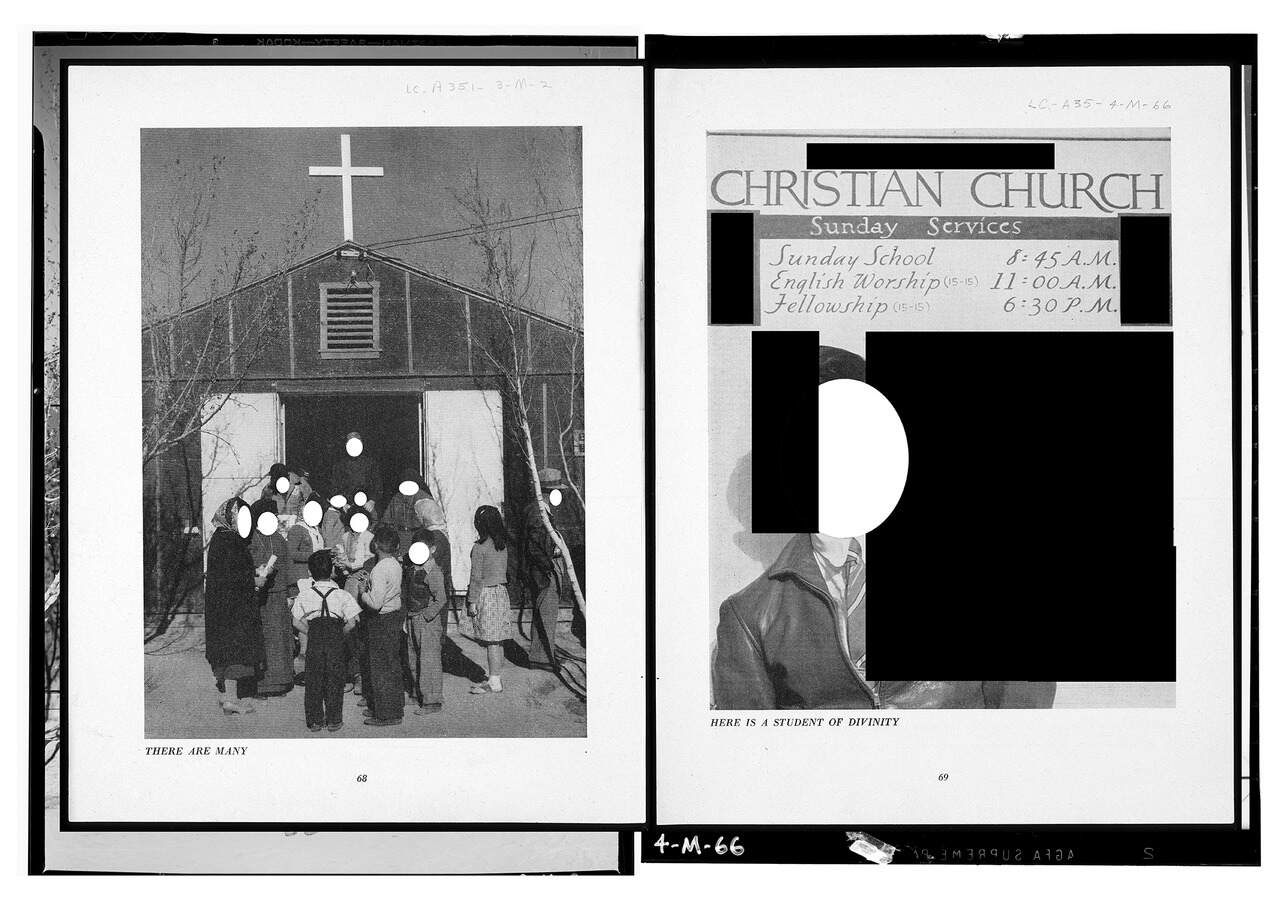

In the summer of 2017, a few years after Joe had also passed away, I traveled to the remote hill town of Satriano, Calabria, in southern Italy, where he and my grandfather were born, intending to make a series of photographic portraits about my paternal ancestry. Earlier that year, President Trump had passed Executive Order 13769, commonly referred to as the Muslim Ban, an action challenging entry to the United States by nationals from predominantly Muslim countries. As I traveled through the Calabrian countryside, I remember seeing the sign for the town of Maida, my surname, which coincidentally is also a Japanese name (毎田). Pronouncing the name in my head, MAI-DA, I drew a parallel between the Immigration Exclusion Act of 1924, passed the year my great uncle was born in Satriano; the incarceration of Japanese Americans in the United States during World War II, which targeted citizens like Katherine’s extended family; and the bias against Muslims, as embodied by Trump’s legislation from earlier that year.

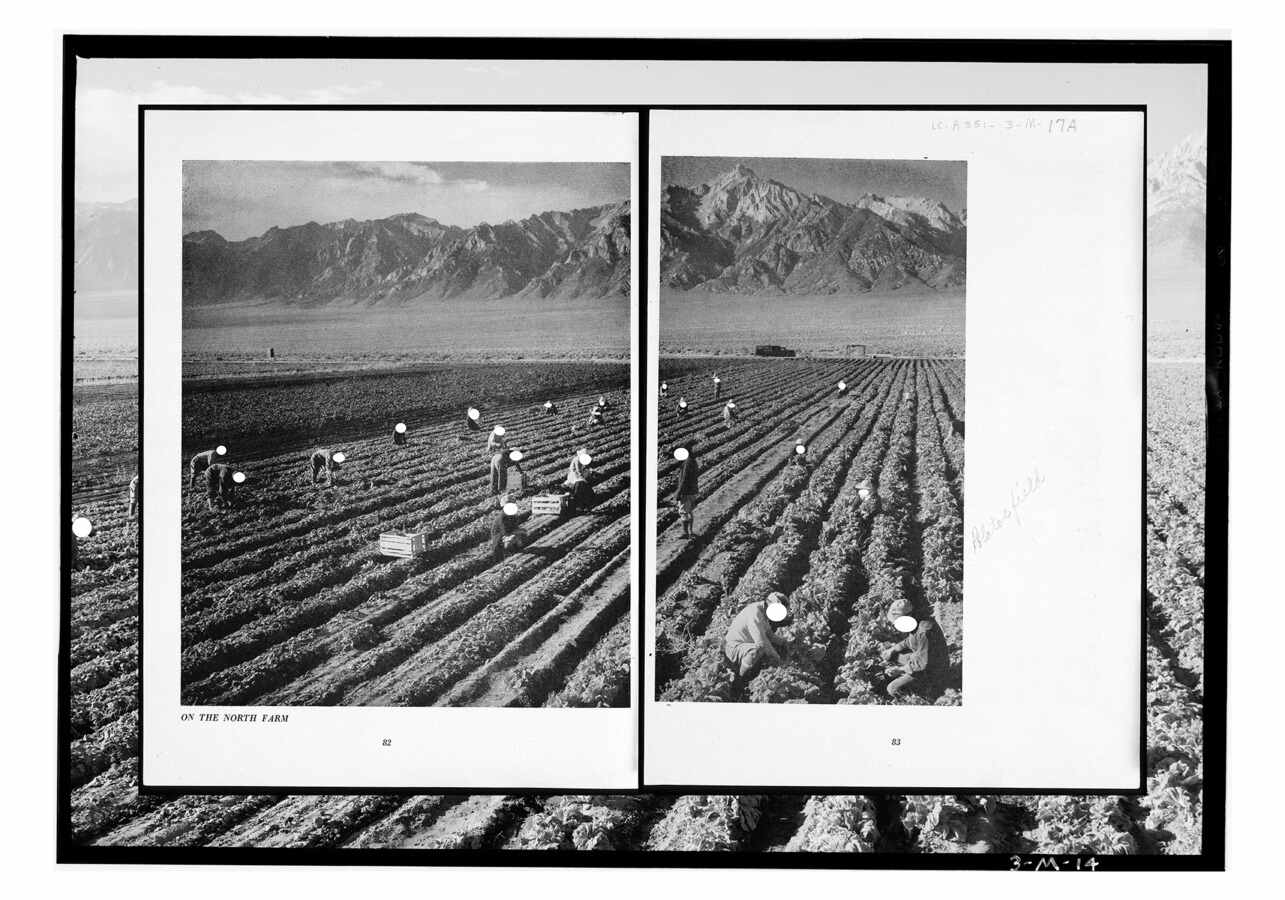

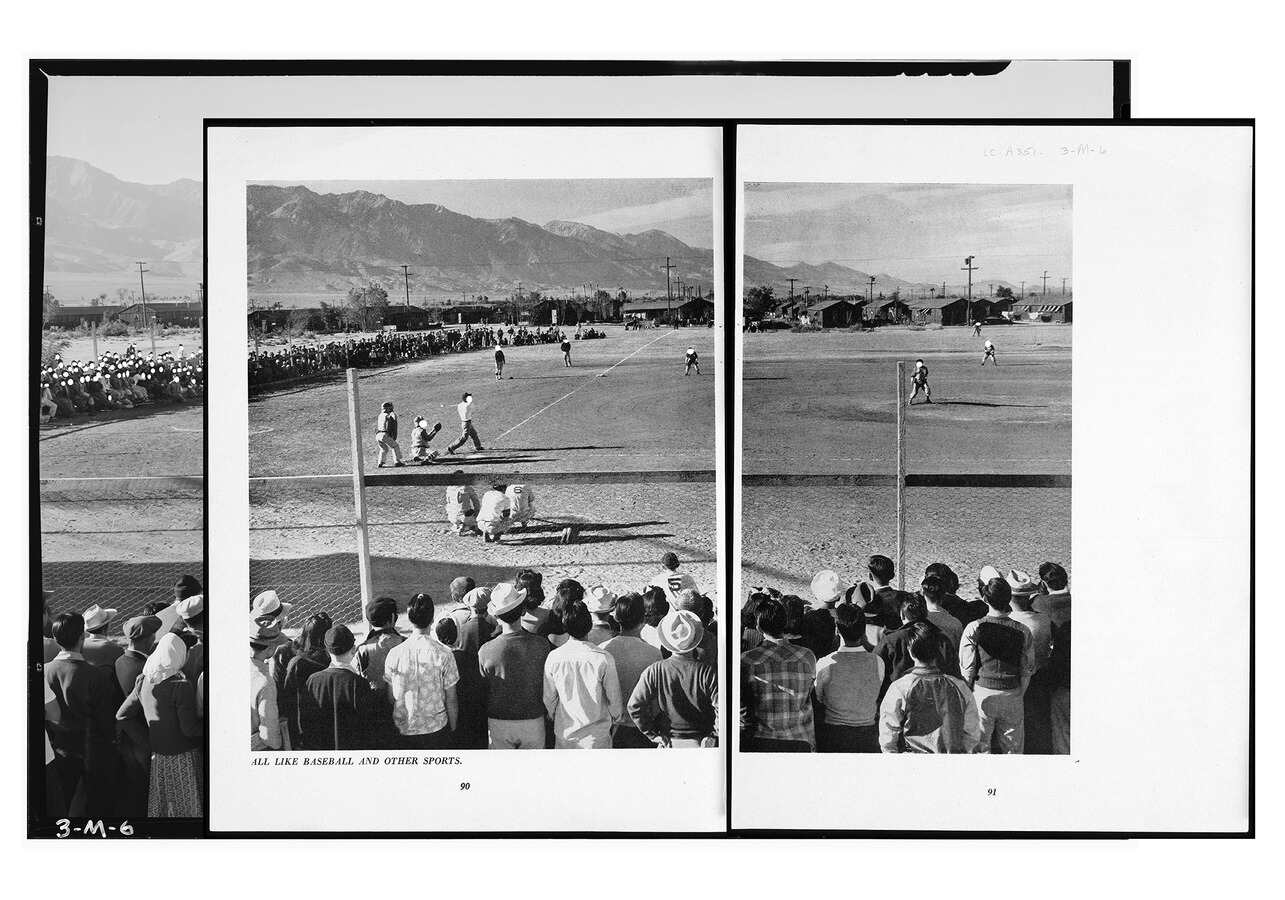

On my hard drive, I had previously downloaded from the Library of Congress all of Ansel Adams’s 1943 photographs from Manzanar, in which he documented wrongfully incarcerated American citizens of Japanese ancestry. As I considered this set of images in Italy, on my great uncle’s native soil, Adams’s archive seemed as relevant as ever.

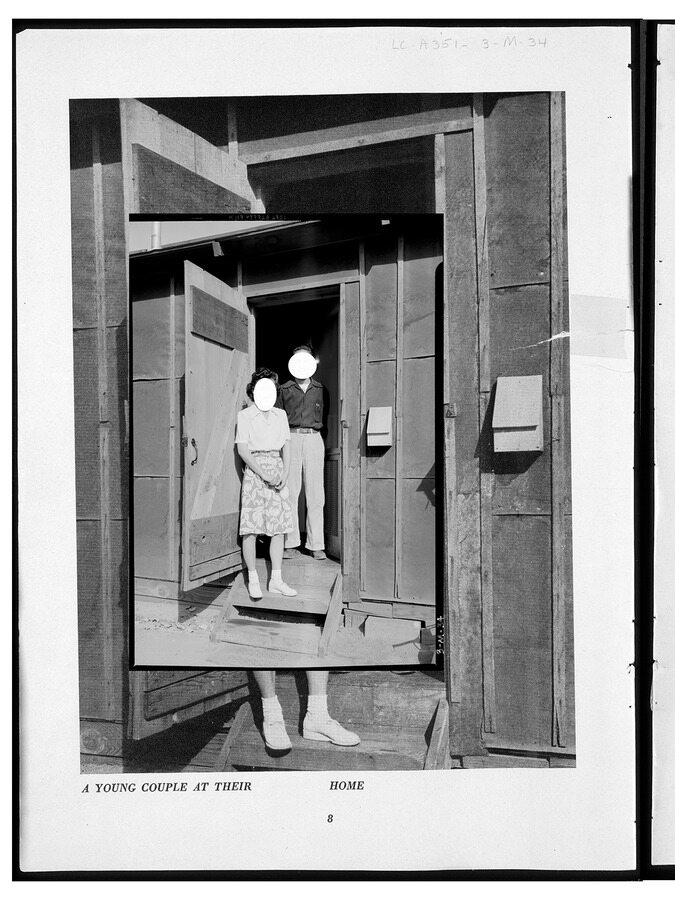

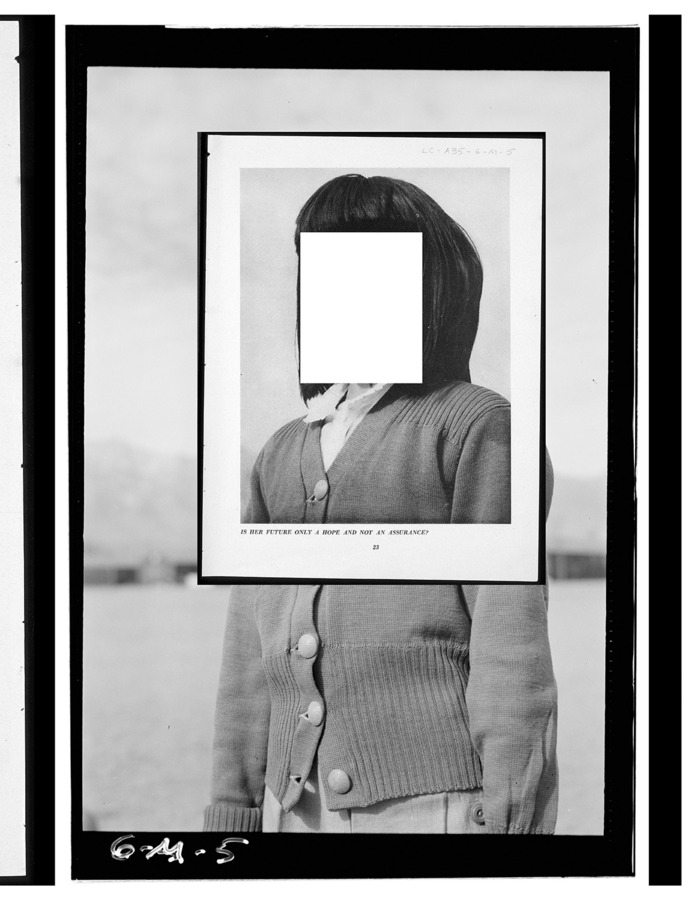

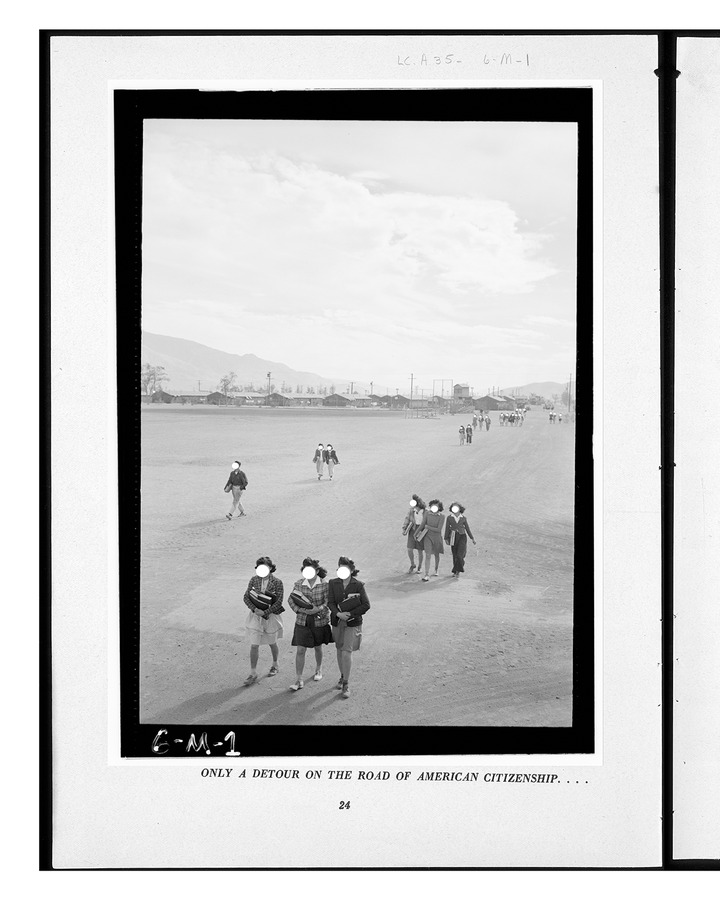

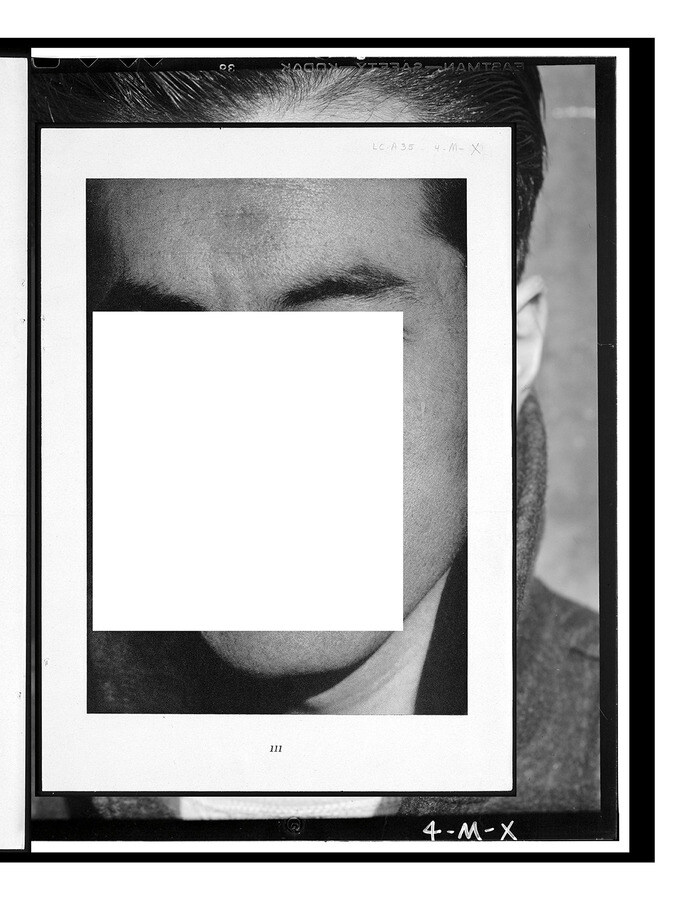

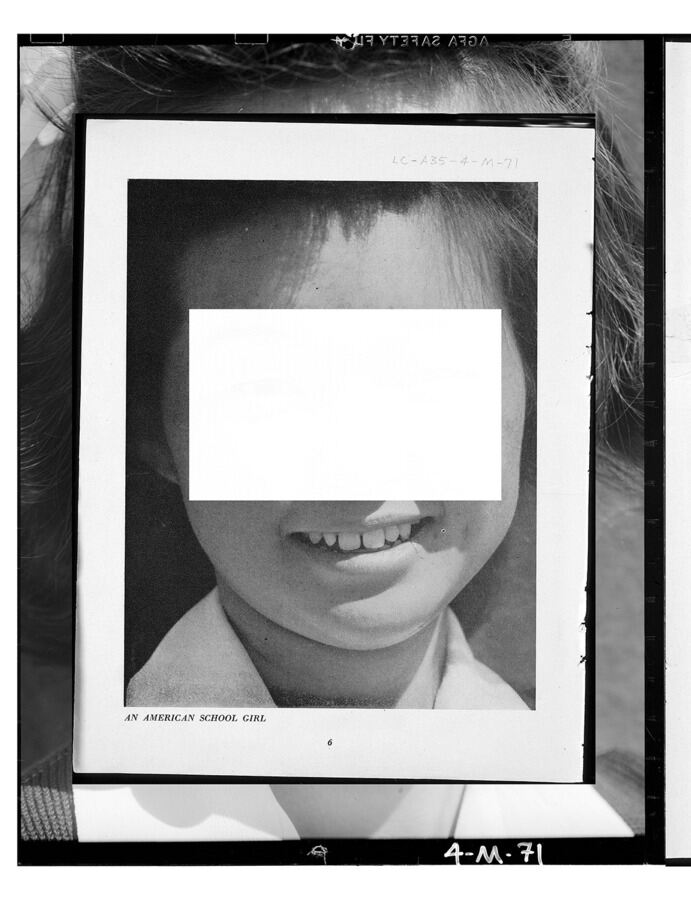

In 1965, when Adams donated his World War II photographs of Japanese Americans interned at the Manzanar Relocation Center in California to the Library of Congress, he wrote, “I think this Manzanar Collection is an important historical document and I trust it can be put to good use.” Although the photography department at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, exhibited this work in 1944, under Nancy Newhall’s leadership, and the work was published in an accompanying monograph, the project was poorly received, perhaps contributing to Adams’s decision to donate the archive and to let its copyright eventually expire. In response to Adams’s prompt to put his work “to good use,” I spent that summer in Calabria reconstructing his Manzanar archive and his 1944 publication, Born Free and Equal: The Story of Loyal Japanese-Americans to create my own book, Born Free and Equal: The Story of Loyal ______-Americans.

This essay originally appeared as a foreword to Joseph Maida’s monograph, Born Free, Born Equal.