Alice Notley’s Roving “I”

In Being Reflected Upon, a memoir in verse, the poet moves through the moments of her life with an almost cosmic sense of knowingness.

Alice Notley.

(Photo by David Barnes)

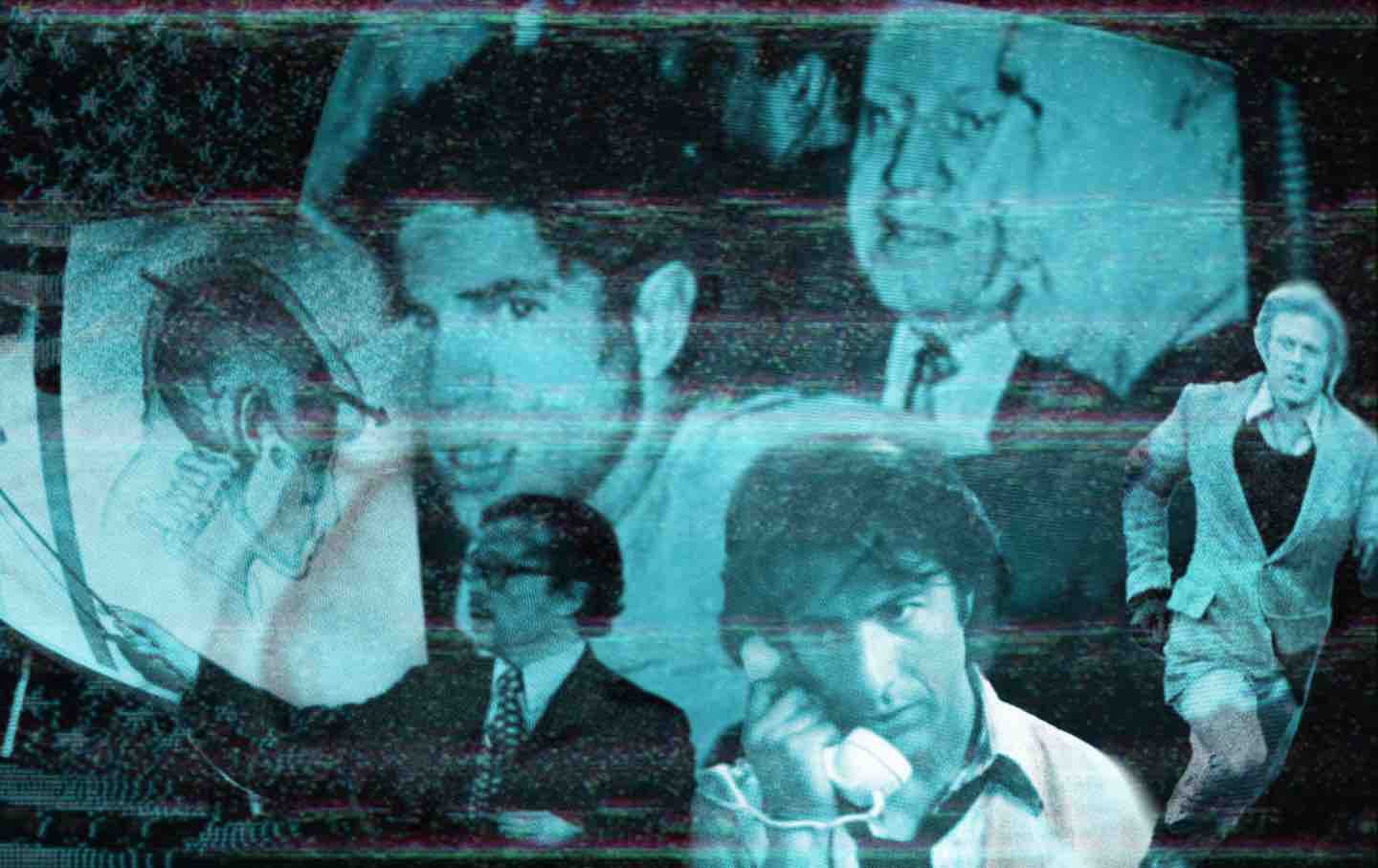

When I was a kid, TV came from Phoenix or Las Vegas, and it was always going in and out. I liked having a gritty screen you couldn’t see very well. I liked not being able to see the story. I can’t stand the big clear image.

—Alice Notley, interviewed by Janique Vigier in Harper’s, April 2024

In the preface to her new book Being Reflected Upon, a “memoir in verse,” Alice Notley says she “was trying to find out if anything had happened” between 2000 and 2017, a period in her life bookended by the death of her second husband, the poet Doug Oliver, in 2000 and the conclusion of her treatment for breast cancer in 2017. During these years, Notley published 17 books, including Disobedience (2001), a long-form poem with fictional elements, including an ongoing dialogue with a noir detective alternately named Hardwood, Hardware, and Mitch-ham; Alma, or the Dead Women (2006), “an epic narrative poem written mostly in prose,” about a god who shoots heroin and takes the form of an owl; and Culture of One (2011), a “verse novel” about Notley’s “hero” Marie, a woman who lived at the dump near where Notley grew up in Needles, California. She also edited two posthumously published works by Oliver and coedited, annotated, and introduced The Collected Poems of Ted Berrigan (her first husband) while undergoing the “legendarily grueling” treatment for hepatitis C, the disease responsible for Berrigan’s death, which Notley contracted in the 1970s from injecting amphetamines (“I did it for about a year,” she says about her drug use in “Trying to Get to Desert Hole,” “but it wasn’t very im- / portant to me not as much as owls these short ones / rather long-legged living anywhere”).

Books in review

Being Reflected Upon

Buy this bookThe almost comical juxtaposition of Notley’s query (“what had been going on?”) with this list of significant life events might point to what she’s after in Being Reflected Upon: She skims and glides over what is typically considered noteworthy in a biographical sense—what one “should” put in one’s memoir—because she’s searching for other answers. Notley’s defiant interpretation of the memoir form is not surprising, since her oeuvre is built on a stance of disobedience; and because the idea of genre is most interesting as a constraint to be questioned, troubled, or resisted, her unruly treatment of it is gratifying to read. “There’s so much I don’t need to tell you / the detail is what you say it is I hate that,” she writes in “Le Mâitre du Désordre,” which could be read as a rebuttal of autobiography at large.

Notley is 78 years old; she’s lived a long and interesting life among poets, artists, and musicians; but any reference she makes about her proximity to cultural and literary celebrity (and, of course, Notley is a literary celebrity herself) serves another purpose, as in “Polluted,” when she writes:

I just crossed out lines about watching a film with Eddie

ancient Village folksingers remembering Dylan

I remember Mississippi John Hurt at the Bitter End

I could say or who got rich and famous what was that

all about I am the crossroads what’s happening

I’m what’s happening porous and permeated with scorching light.

This passage is an example of an insistent refrain that runs throughout the book: the idea that the “newsworthy” events of Notley’s life are never as important as the “I,” the speaker of the poems, a godlike figure who creates the only reality that matters. According to Notley, a poem is “basic and ongoing creation / of the universe in terms of its particles as I speak / it.” In opposition to the traditional idea of the memoir, in which an “I” builds a credible self-portrait for the reader with anecdotes, explanations, and recollected experiences, Notley’s memoir argues for an “I” who transcends the limitations of personality and earthly circumstance: “the voice is always stronger than I am,” she says, “coming from / somewhere other than the physical equipment.”

The “I” of Being Reflected Upon is mercurial, alternately expansive (“I am universal I am re-creating / love, time, and all conditions”), nonhuman (“I am beautiful existence roadrunner, scorpion / I am the swooping-down owl of what will come”), and molecule-sized (“I say ‘I’ so you can understand me / but only I know what I am / at this micropoint in the wind that I am also”). This “I” is inherently antagonistic to the solidification of identity via biographical detail: “I have no character I am a mind / I play at having a personality investing nothing / in it and Care for this body which we have all / dreamed up together,” Notley writes in a poem ostensibly “about” the death of her second husband. Notably, this rejection of a bodily self seems, among other things, to be a vigorous effort to reclaim narrative and spiritual power from the grief and destruction of physical life (and the mindset, beset and potentially victimized, that might result from it): “why would / Anyone want to be trapped in a body on earth”.

In “The Fortune Teller,” her memorial to the poet Joanne Kyger, Notley bristles at the male poets who said that Kyger was “becoming more autobiographical” in her work: “no she wasn’t,” Notley insists, “she was doing mind/nature/voice partic- / ular to person/life finds expression as ‘that flicker.’” Here, the flicker—like Notley’s sense that the writing of a poem is “basic and ongoing creation”—alludes to how elemental forces of life and spirit move through the individual (poet) who is willing to receive them (and put them to paper). Notley’s “I” is an unfixed point, an omniscient position, a seer with access to “The Old Language,” her conception of the original and universal speech of the living and the dead, which she “translates” from to write her poems. “[I]n The Old Language,” she says, “you don’t have to explain.”

At the conclusion to the book’s short preface, Notley arrives at something like an answer to her own question (“what had been going on?”): “I discovered I was an unabashed location of unreported events of the Spirit, or Timelessness, the real name of Consciousness,” she writes, gesturing toward an “I” that, due to its fixed nature on the physical plane (a “location”), serves as site and host to a range of visions and visitations. She imagines the people and events of her life stacked together as “one thing all together”—“an expanse of timelessness” rather than a chronological procession—which allows her to change “the past the present and future by blending them.” This, indeed, is how the book’s poems work or express themselves, and how time functions in our lives as we age (if it can be said to function): Everything is hitched to everything else; in any particular “memory” are the layers of other “memories”; the child we were can be found in the adult we become; and a kind of circular logic emerges wherein “all history’s happening at the same time.”

The book takes its title from “Essay on Style,” a poem by Frank O’Hara that playfully weaves the details (“someone else’s Leica sitting on the table”) and irruptions (“wouldn’t you know my mother would call / up / and complain?”) of the writer’s life with ideas about language and form. While “sitting in JACK / DELANEY’S looking out the big race-track window / on the wet / drinking a cognac while Edwin [Denby, presumably] / read my new poem,” the speaker recounts, “I was reflecting the other night meaning / I was being reflected upon that Sheridan Square / is remarkably beautiful.” In this reversal, the act of reflection—to think deeply and carefully—converts the thinker into a reflective surface: both subject and object, active and passive. In Notley’s vision, she “became the one who held things together as they, the things, kept their motions going, being reflected upon me.” The notion of the poet—the multifarious “I”—as a still, hard surface calls to mind another recurring image in the book: that of the “stele or slab large dark or bronze / that the poems were already written on but with an / ongoing change of individual letters like an old- / fashioned railroad time of departures board.” The stele—typically an ancient monument, signpost, marker of graves and battlefields—as envisioned by Notley exists in a “vast green room” without boundaries, where some part of her continually resides. We might think of the stele—strong, vertical, taller than it is wide—as yet another version of the “I,” another version of the poet upon whose surface the restless events of life continue to move and evolve, even as she writes them down.