What the Photoshop Panic Should Have Taught Us About AI

In 2004, a doctored political image caused outrage and confusion. Twenty years later, why hasn’t visual literacy improved?

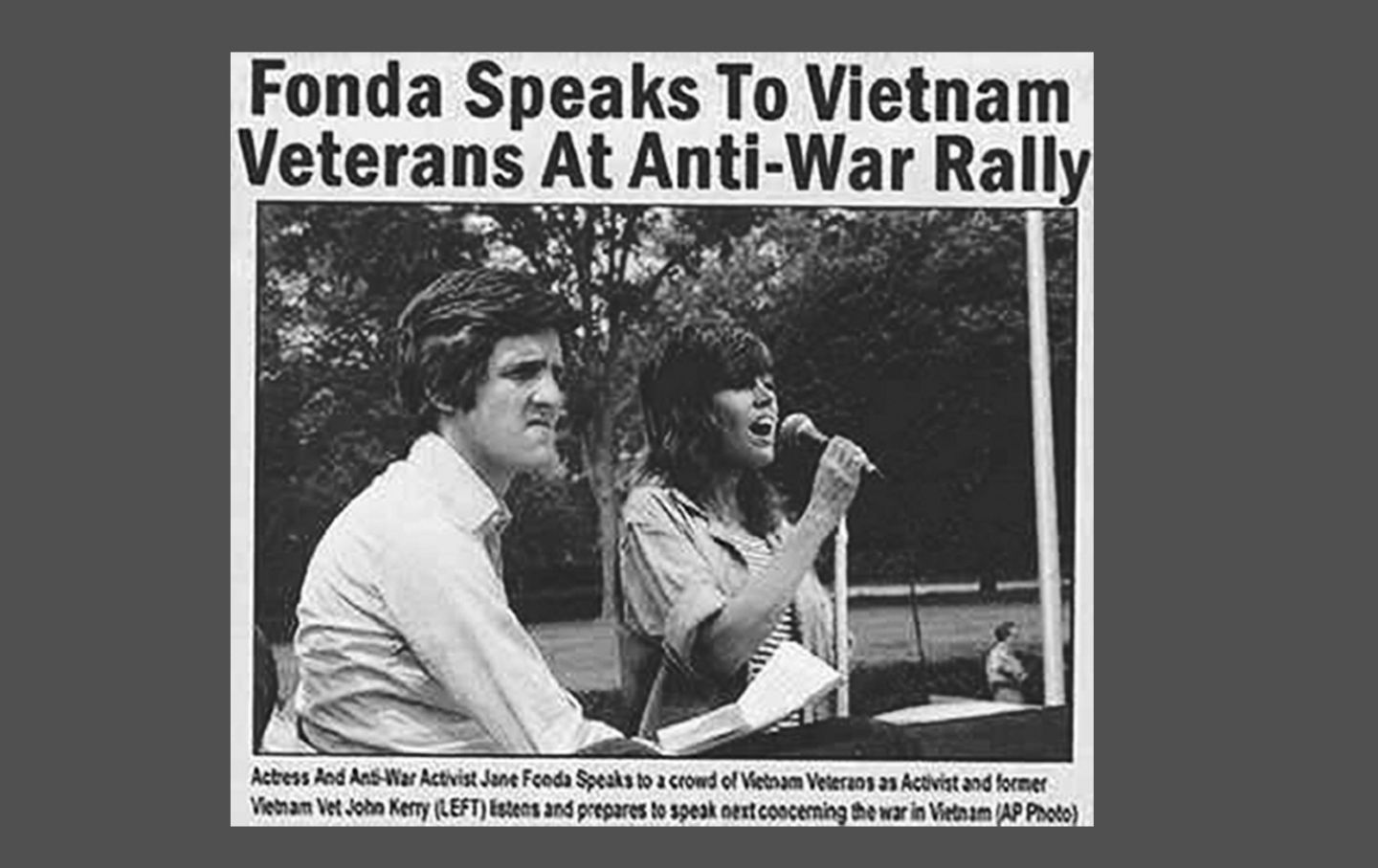

Image created by merging two photographs, showing presidential candidate John Kerry and actress Jane Fonda, who campaigned against the Vietnam War in the 1970s.

(Public Domain)In 2004, an image of John Kerry and Jane Fonda circulated online, in newspapers, and on cable TV. The two seemed to be sharing an outdoor stage sometime during the late 1960s or early ’70s. Conservative pundits like Rush Limbaugh and Sean Hannity went crazy over the image: It seemed to suggest that the centrist Vietnam vet Kerry had aligned himself with “Hanoi Jane” and the “traitorous” far left. The New York Times published a piece about the picture, outlining conservatives’ search for a connection between Kerry and Fonda, and then a week later, the photo and its credit from AP News were debunked as fakes. What was at work here was not evidence of comrades in arms, but rather really good Photoshop.

If I introduced this image with that description to a classroom of my college students, they might immediately fall asleep: After all, only the oldest among them are capable of dreaming about the former Democratic presidential candidate made of ketchup and wood. And by now, they’re also inured to fake images made by AI, which they see all over their Instagram and TikTok feeds. But in 2004, this altered photo was news, an election-year flashpoint that seemed to show Kerry’s radical roots as he tried to appeal to the country’s center.

Last year, after the attempted assassination of Donald Trump, images instantly circulated online of the president raising a defiant fist, flanked by Secret Service agents. In slightly different versions of this photo, the agents are smiling, prompting speculation on both sides of the political spectrum that the assassination attempt might have been faked to bolster Trump’s platform. Soon after, the smiling image too was deemed a fake. The happy-agents version had been altered by someone on the Internet using AI.

These two image snafus occurred 20 years apart. In that span of time, we have seen a technological revolution: the rise of smartphones, social media platforms, self-driving cars, drones, VR headsets, 3D printers, hoverboards (but not the kind we all actually wanted), and more. But what, shockingly, hasn’t seemed to change, is our visual literacy. Just as in 2004, the prospective voting public in 2024 was still duped by a picture roaming around the Web. How come we didn’t learn our lesson?

Concern over what the digital revolution might mean for photography, and how the cultural relevance of the photograph would change, had been mounting for at least two decades by the time the Kerry/Fonda image first appeared on a conservative website called “vietnamveteransagainstjohnkerry.

com.” (But don’t go there looking for evidence… it’s currently a parked hub for what appears to be an Indonesian gambling site).

The first time we really started talking about the possibility of digitally manipulating photographs was in 1982, when a National Geographic cover showed camel riders in front of the pyramids at Giza and, shortly after publication, it came to light that the magazine had used new digital editing software to move the pyramids closer together, without the photographer’s permission. Former Nat Geo editor in chief Susan Goldberg discussed this incident a generation later in a 2016 piece for the magazine and claimed that “a deserved firestorm ensued,” in the ’80s, including from within the publication itself, which caused the magazine to quickly reverse its stance on altering photographs. This unease about the possibility that our own eyes could fool us continued as the millennium approached. There was widespread concern among scientists and government agencies that medical and scientific results could be faked through digital images. In a 1994 issue of Science Magazine, the authors of a piece on “easy-to-alter digital images” claimed that “digital image fraud can be accomplished without a trace.” Shocker of shockers, manipulated photos began darkening the hallowed halls of tabloid magazine culture. In 1997, the Daily Mail published photos of Princess Diana weeks before her death, artificially rotating Dodi Al Fayed’s head to make it look like the two were about to kiss—a preview of all the Putin deepfakes and Studio Ghibli deportation memes to come.

By 2003, digital camera sales would outpace those of film cameras for the first time, mostly the kind of point-and-shoot models that you could pick up at a Best Buy or Radio Shack for a few hundred bucks. Around this time, the concerns around digital imagery seemed to shift from existential to more specific, and generally the public furor around the deceptive capabilities of these images subsided. There were so many ethical discussions around the airbrushing of celebrities on magazine covers, but less, for some reason, about the complete collapse of photographic truth.

One possible explanation for why this conversation died down in the aughts is that, as more people used digital cameras and messed around with early versions of Photoshop, there was a collective realization that “faking” reality with those tools was still relatively challenging, at least to do well, and therefore, fakes wouldn’t run rampant. Gawking at Photoshop fails remains a fun way to kill time: The eerily stretched necks? The missing arms that created a sleeker profile? These images also prove how even professionals, when rushed, could warp the supposed “truth” beyond believability. Still, somehow the joyful hunt to find these occasional errors in Photoshopping failed to translate to the media literacy required for the new age of AI.

Of course, the barrier to entry into photo manipulation has steadily lowered over the last two decades. Smartphone cameras made photography more accessible, causing a spike in the number of images made and consumed. Throughout the 2010s, when people started using Instagram and Snapchat, simple AI filters were introduced that made minor adjustments like blurring backgrounds, removing figures, or adding animal ears to a human head a cinch. Since then, software like Midjourney, which allows for the creation of photographic-looking images never captured by a camera, has made headlines, but use of AI has been woven into the programs we use for much longer.

In a perfect world, as children began spending more time online consuming images, introductory arts education would have allowed for lively classroom discussions of what it means for a photograph to “tell the truth” as kids’ worlds became increasingly image-saturated.

Of course, the 2000s didn’t see an explosion of funding for arts education, with the No Child Left Behind act prioritizing subjects that could be covered on a standardized test. Even as kids were expected to live in an increasingly image-saturated world, classes where images were discussed critically were treated as extra. Even for students who went on to four-year colleges, general education requirements often only allowed for one or two arts classes if students wanted to graduate in four years.

Making sure most young people received a crash course in media literacy didn’t need to mean more photography majors (although, as a photo professor, I don’t hate that idea). But another good solution would’ve been to acknowledge visual literacy issues across curricula: in civics classes, in arts classes, hell, even in homeroom. There was such an unaddressed need, generally, to contend with the fact that students are bombarded by visual information and could benefit from learning to analyze it more critically.

Educating kids should have been the easy part. A huge gap in visual literacy exists among those who were full-blown adults during the digital revolution, and who are now among the least prepared to analyze AI images. I recently scrolled past a group of images on my social media feed, shared by a friend in her 70s, showing Bruce Springsteen and Bob Dylan standing side by side. Three images looked to be photographs taken during concerts, but in a fourth image, Springsteen is pressing a normally stoic old Bob’s weeping face to his breast. The post’s clearly AI-generated caption weaved a tale of what the viewer was supposedly witnessing: “Later, backstage, Dylan looked at him and said, ‘If there’s ever anything I can do for you…’ Springsteen, nearly speechless, replied, ‘You already did.’”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →While this text reads like the kind of sparkly fan fiction that would ignite most people’s intrinsic suspicions, there was debate in the comments section over the image’s veracity—or if the truth here even mattered. “I totally buy Dylan crying and Bruce comforting him,” one commenter wrote. “And even if it is AI, so what? It’s a good message.”

It is now possible to type a short sentence, hit that you’d like the image to appear “photographic,” and create a scene that never happened. Sometimes, the images show errors that hint at their AI origins, but more and more, the images read as perfect, stock-photo quality renderings of the prompt. The one giveaway is that AI images are often too perfect, too on-the-nose. Over the last few years, many Pinterest users have complained that, instead of the real-world inspiration that drew them to the platform, they are now bombarded by fictional slop of gardens, garments, and other “handmade” pieces created completely by AI. An unfathomable number of photographic images were already being created each day, and now, new generation technology has multiplied beyond comprehension.

One important lesson that we all should have learned over the last generation of rapid image production, manipulation, and consumption is that photographs, and images in general, never exactly show “the truth.” As Susan Sontag wrote in her essay “In Plato’s Cave,” “Although there is a sense in which the camera does indeed capture reality, not just interpret it, photographs are as much an interpretation of the world as paintings and drawings are.”

Even the most straight documentary photograph needs to be viewed with the knowledge that, just out of frame, something lingers that could change the entire narrative. Today, we are forced to contend with AI models that were trained on a bank of images, most of them photographs, and a new constellation of pictures swallowed and then reconstituted into new forms that we should have been more prepared to interpret.

The question raised by the Bruce-caressing-Bob supporter’s comment is a question worth asking. Does it matter if the image was made by AI? And what should we bring to the table as viewers who must confront thousands of images each day? While the answers are important, it is more crucial that we all reckon with the questions, and that includes the kids that we’re throwing into this confusing pictorial ocean. The goal shouldn’t be to avoid ever being “duped.” Anyone who consistently aces those “AI or photo” quizzes should be very proud of themselves, but there also is no such thing as an infallible viewer. What’s most important is that we are always questioning images, thinking deeply about them, and understanding how what they communicate could be transformative. The most dangerous thing a person can be is a casual, uncritical viewer.

Your support makes stories like this possible

From Minneapolis to Venezuela, from Gaza to Washington, DC, this is a time of staggering chaos, cruelty, and violence.

Unlike other publications that parrot the views of authoritarians, billionaires, and corporations, The Nation publishes stories that hold the powerful to account and center the communities too often denied a voice in the national media—stories like the one you’ve just read.

Each day, our journalism cuts through lies and distortions, contextualizes the developments reshaping politics around the globe, and advances progressive ideas that oxygenate our movements and instigate change in the halls of power.

This independent journalism is only possible with the support of our readers. If you want to see more urgent coverage like this, please donate to The Nation today.

More from The Nation

Is it Too Late to Save Hollywood? Is it Too Late to Save Hollywood?

A conversation with A.S. Hamrah about the dispiriting state of the movie business in the post-Covid era.

The Melania in “Melania” Likes Her Gilded Cage Just Fine The Melania in “Melania” Likes Her Gilded Cage Just Fine

The $45 million advertorial abounds in unintended ironies.

Nobody Knows “The Bluest Eye” Nobody Knows “The Bluest Eye”

Toni Morrison’s debut novel might be her most misunderstood.

Melania at the Multiplex Melania at the Multiplex

Packaging a $75 million bribe from Jeff Bezos as a vapid, content-challenged biopic.

Ishmael Reed on His Diverse Inspirations Ishmael Reed on His Diverse Inspirations

The origins of the Before Columbus Foundation.

How Was Sociology Invented? How Was Sociology Invented?

A conversation with Kwame Anthony Appiah about the religious origins of social theory and his recent book Captive Gods.