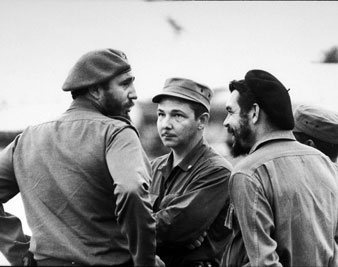

Mary Evans Picture Library/SALAS COLLECTION/Everett CollectionFidel Castro with Che Guevara and Castro’s brother Raul (center) in Havana, Cuba. 1959

Mary Evans Picture Library/SALAS COLLECTION/Everett CollectionFidel Castro with Che Guevara and Castro’s brother Raul (center) in Havana, Cuba. 1959

Fidel Castro says his country is in desperate shape and can only be rescued by a revolutionary government.

Oriente Province, Cuba

Cuba’s land situation, the problems of industrialization, living standards, unemployment, education and public health: these are the problems—along with the attainment of civil liberty and political democracy—to the solution of which the revolutionary 26th of July Movement directs its efforts.

This presentation may seem cold and theoretical to the reader, unless he is familiar with the fearful tragedy which our country is living through.

At least 85 percent of Cuba’s small-scale farmers rent their land, and face the constant threat of eviction. More than half of our best arable land is in foreign hands; in Oriente, the broadest province of Cuba, the lands of The United Fruit Company and of the West Indies Fruit Company unite our northern and southern shores. Throughout the country, 200,000 rural families are without a square foot of land on which they can support themselves; yet almost ten million acres of untouched arable land remain in the hands of powerful interests. Cuba is primarily an agricultural country. The rural areas were the cradle of our independence; the prosperity and greatness of our nation depend on a healthy and vigorous rural population, willing and able to till the soil, and on a state which protects and guides that population. If this is so, how can the present situation be allowed to continue?

Except for a few food-producing industries and some woodworking and textile plants, Cuba is essentially a producer of raw materials. She exports sugar and imports candy; she exports leather and imports shoes; she exports iron and imports plows. Everyone agrees that there is a great need to industrialize: that we lack metal, paper and chemical industries; that the techniques of agriculture and animal husbandry must be improved; that our food-producing industries must be expanded to meet the ruinous competition of European cheese, condensed milk, liquors and cooking oil, and of American canned foods; that we need a merchant fleet; that the tourist trade is a potential source of great income. But the possessors of capital keep the people bowed under ox-yokes, the state folds its arms, and industrialization will wait for kingdom come.

As bad, or worse, is the tragedy of our housing situation. There are about 200,000 huts and shacks in Cuba; 400,000 rural and urban families live crowded in slums without the barest necessities of sanitation. Some 2,200,000 Cubans pay rents which absorb from one-fifth to one-third of their incomes, and 2,800,000 of our rural and suburban population are without electricity. In this matter we are blocked in the same way: if the state proposes a reduction in rent, the proprietors threaten to paralyze construction; if the state does nothing, the owners build only so long as they can foresee high rents. The electric-power monopoly acts the same way: it extends its lines only so far as it can visualize a good profit; beyond that point, what matters if the people live in the dark? The state folds its arms and the public remains without adequate housing or light.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

Our educational system is a perfect complement to the situations just described. In a country in which the farmer is not master of his land, who wants agricultural schools? In our non-industrialized cities, who needs technical and industrial schools? All this follows the same absurd logic: since we have none of one thing, there is no need for the other. Any typical small European country boasts more than 200 technical and industrial-arts schools; in Cuba there are only six—and graduates go forth with their degrees only to find that there is no work for them. Less than half of our rural children of school age can attend school; and they go barefoot, ill-clothed and ill-fed. Often the teacher must buy the necessary school supplies out of his own salary.

Only death frees people from such poverty, and in this solution the state cooperates. More than 90 percent of the children in our rural areas are infested with parasites which enter the body through bare feet. Society is greatly moved by the kidnapping or murder of a single child, but it remains criminally indifferent to the mass murder of our children through lack of proper care.

And when a father works only four months a year, as do some 500,000 sugar-workers, how can he afford medicine and proper clothing for his children? They will grow up with rickets; at thirty, will not have a sound tooth in their mouths; and having heard a million speeches, will die in poverty and disillusionment. Access to our always-crowded state hospitals is almost impossible without the recommendation of some politician, whose price is the vote of the sufferer and his family—a vote that insures the continuation of this evil.

In such conditions, is it surprising that from May to December we have more than a million unemployed, and that Cuba, with a population of 5,500,000, has more people unemployed than either France or Italy, whose populations exceed 40,000,000?

The future of the country and the solution of its problems cannot continue to depend on the selfish desires of a dozen financiers, on the cold profit-and-loss calculations of a few magnates in air-conditioned offices. The country cannot continue to beg, on bended knee, for miracles from a few “golden calves.” Cuba’s problems will only be solved if we Cubans dedicate ourselves to fight for their solution with the same energy, integrity and patriotism our liberators invested in the country’s foundation. They will not be solved by politicians who jabber unceasingly of “absolute freedom of enterprise,” the sacred “lady of supply and demand” and “guarantees of investment capital.”

A revolutionary government, with the endorsement of the nation, would rid our institutions of corrupt and mercenary bureaucrats, and proceed immediately to the industrialization of the country—mobilizing all our idle capital, which amounts to more than 1.5 billion pesos, through the National Bank and the Bank for the Promotion of Agriculture and Industry. This great task of planning and administration must be put in the hands of men of absolute competence, who are completely outside the sphere of politics.

A revolutionary government, after installing as owners of their plots the 100,000 small farmers who now rent their land, would proceed to a final settlement of the land problem. First, it would establish—as the constitution requires—a maximum size for each type of agricultural holding, expropriating the excess acreage. Thus public lands stolen from the state would be recovered, marshes and swamplands drained, areas set aside for reforestation. Second, the revolutionary government would distribute the remainder of the expropriated lands to our rural families (giving preference to the largest), sponsor the formation of agricultural cooperatives for the joint use of expensive farm machinery and refrigerated storage facilities, and provide guidance, technical knowledge and equipment for the farmer.

A revolutionary government would resolve the housing problem by resolutely lowering rents by 50 percent, exempting from taxation all houses occupied by their owners, tripling taxes on rented buildings, demolishing slums to make way for modern, many-storied buildings, and financing construction of dwellings throughout the island on an unprecedented scale. If the ideal in the country is that every family should own its parcel, the ideal in the city must be that every family lives in its own house or apartment.

We have sufficient stones and more than enough hands to create a decent residence for every family in Cuba. But if we continue to wait for miracles from “the golden calves,” a thousand years will pass and nothing will change.

Finally, a revolutionary government would proceed to the integral reform of our educational system.

Cuba can easily support a population three times what it is now. There is no reason, then, why misery should exist among its present inhabitants. The markets should be full of produce; the pantries of our homes should be well-stocked; every hand should be industriously at work. No, this is not inconceivable. What is inconceivable is that there should be men who will accept hunger while there is a square foot of land not sowed; what is inconceivable is that 30 percent of our rural folk cannot sign their names and that 90 percent know nothing of Cuban history; what is inconceivable is that the majority of our rural families live in conditions worse than those of the Indians whom Columbus found when he discovered “the most beautiful land that human eyes have seen.”