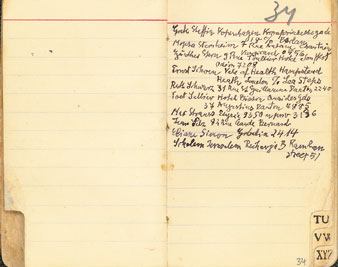

Benjamin ArchiveWalter Benjamin’s Paris address book, 1930s

Benjamin ArchiveWalter Benjamin’s Paris address book, 1930s

Among the many writers and intellectuals whose posthumous fame far outshines that of when they were alive–Kafka, say, or Emily Dickinson or even Machiavelli–Walter Benjamin is the object of a particular kind of obsession. In Germany, even his address book from his years of exile has been deemed worthy of publication in a facsimile edition. And in the English-speaking world, within the past decade Harvard University Press has released the complete four-volume edition of Benjamin’s Selected Writings; his massive, essentially unfinished and previously unpublished magnum opus, The Arcades Project; and a series of separately issued mass-market paperback editions of his posthumously published memoir (Berlin Childhood Around 1900), his ruminations on the hashish experiments he conducted in the late 1920s and early ’30s (On Hashish) and his various writings on Charles Baudelaire (The Writer of Modern Life). All of these books are today in wide circulation and enjoy the kind of visibility and sales otherwise common to trade publications. Such notoriety would have been unfathomable in Benjamin’s lifetime, especially during his final years, when what little prominence he attained in the second half of the Weimar Republic was on the wane. In a way, every posthumous edition of Benjamin’s work, be it a collection of writings (finished or unfinished) or a facsimile edition of personal ephemera, is an address book, a volume that his admirers can consult in their quest for reliable coordinates about a writer who led a restless intellectual and personal life that came to a mysterious end.

The most recent addition to this ever expanding Benjamin list is The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility, a collection of some forty-five pieces–most of them unpublished while he was alive, many of them little more than fragments–on art, film, photography and other media. The volume takes its name from the much heralded title essay of the collection, a highly demanding exercise in cultural criticism that offers at once a sustained analysis of aesthetics, politics and society in the age of late capitalism and a subtle elaboration of the ever changing modes of sensory experience. The essay was composed during a particularly difficult period of Benjamin’s Parisian exile, in the autumn of 1935, and was later subjected to a series of stringent revisions: in a detailed letter sent from London, Theodor Adorno expressed his reservations concerning a putative strain of romanticism in the piece and a regrettable lack of dialectical rigor. It finally appeared, in abbreviated form and in French translation, in 1936 in Max Horkheimer’s Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung. The version selected for the new Harvard edition includes seven manuscript pages that were lopped off in the first published edition; it is what Benjamin considered the Urtext, or “master version,” and best represents what he had hoped to see in print.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

Despite its theoretical complexity and elusive terminology, not to mention the clunkiness of the English title, the so-called “Work of Art” essay has become one of Benjamin’s best-known pieces of writing, a staple of media studies courses and artist statements. (When it first appeared in English in the collection Illuminations, published in 1968, its title was the more fluid, if less literal, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.”) In addition to the “Work of Art” essay, the Harvard edition includes an assortment of pieces, transplanted from Benjamin’s Selected Writings, that might together form a kind of media archaeology: his reflections on painting, children’s books, folk art, photography, radio, the telephone and the allure of cinema, from Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin to Chaplin’s The Circus. Long before Marshall McLuhan, Benjamin sought to make sense of the impact of technology on artistic and political expression. Given Benjamin’s penchant for decoding “the unapparent and the everyday,” it’s clear enough what drew him to his subjects of analysis, even if the relatively agnostic position he took often cut against the grain of the more damning critique of the culture industry advanced by his Frankfurt School colleagues. “All Mickey Mouse films are founded on the motif of leaving home in order to learn what fear is,” he wrote in an unpublished fragment of 1931. A shrewd observer of pop culture, who showed by turns sympathy and suspicion, Benjamin could see in Mickey Mouse what others would be more apt to attribute to Homer or the Bible.

The editors and publisher of this volume deserve credit for organizing its contents thematically rather than chronologically. Such a format encourages readers to approach Benjamin’s work discursively, thereby fostering a superior sense of the recurrent ideas, themes, motifs and concepts that Benjamin employed time and again. One odd yet also somehow fitting feature in this protracted moment of cultural adulation is the book’s cover illustration–a caricature of the brilliant, seemingly crazed German thinker, his body formed by the spokes of a printing press, crafted by Ralph Steadman, the British cartoonist otherwise associated with the “gonzo” journalist Hunter S. Thompson. Of course, apart from their respective experiments with hallucinogenic drugs, Thompson and Benjamin have little in common. But they do share a cultish devotion among their readers, who are drawn not only to the writers’ ideas but also to their quirky, ostensibly revolutionary life paths, each of which is shrouded in its own fog of conjecture and mystery.

Esther Leslie’s biography of Benjamin comes at a good time, when the mythologizing of a cultural critic is in need of some sober re-evaluation. Making full use of newly available archival sources and Benjamin’s voluminous correspondence, Leslie insists that her study “holds rigorously to the facts of a life much fictionalized.” While she revisits much of the ground combed over in the two previous full-scale biographies available in English–Bernd Witte’s Walter Benjamin: An Intellectual Biography (1991) and Momme Brodersen’s Walter Benjamin: A Biography (1996)–she does so with more personal insight and also by devoting greater attention to the drama of Benjamin’s private life than solely to the rhythms of his literary, philosophical and scholarly output. Writing for neither specialists nor acolytes, she tactfully avoids the excesses of revisionism and hagiography. She also manages in large part to sidestep the ideological turf wars that defined the early disputes over Benjamin’s status as a thinker and critic, with Gershom Scholem making his case for Benjamin as a Zionist who never quite realized his dream of Zion–in fact, he flirted with the idea of migrating to Palestine throughout the late 1920s–and Adorno playing up Benjamin’s allegiance to the Institute for Social Research, and with both of them separately rejecting Benjamin’s ties to Brecht.

Leslie begins with an account of the assimilated, upwardly mobile German-Jewish milieu into which Benjamin was born in 1892, the bourgeois “ghetto” that was for him Berlin’s West End at the fin de siècle. Benjamin commenced his formal education in 1902 at the Kaiser Friedrich Gymnasium, a thoroughly rigid Prussian institution whose “narrow-chested, high-shouldered impression” he never forgot. As a teenager he was sent to a progressive boarding school in the countryside where, under the aegis of Gustav Wyneken, a charismatic educational reformer, he became active in the youth movement. (Leslie’s book includes a reproduction of a striking postcard titled “Our Swimming Pond” of nude swimming at the school.) Benjamin published his first works of prose and poetry under the pseudonym Ardor in the Wyneken-inspired journal Der Anfang (The Beginning); around the same time he debated the merits of cultural Zionism and immersed himself in the writings of Kant, Kierkegaard and Schiller. Benjamin would ultimately sever his ties to Wyneken, who in 1914 came out as a war enthusiast. For his part, Benjamin did all that he could–feign palsy or, under hypnosis, induce sciatica–to avoid military service in a war he found morally indefensible.

In 1912 Benjamin began his university studies in Freiburg, where he encountered some of Wilhelmine Germany’s most distinguished faculty. He attended history lectures by Friedrich Meinecke and took courses in philosophy with Heinrich Rickert. Generally bored by academia, however, he likened his experience with the professoriate to “a mooing cow to which students were compelled to listen”; in his later essay “The Life of Students,” he asserted, “scholarship, far from leading inexorably to a profession, may in fact preclude it.” Benjamin would maintain a deep skepticism toward academia throughout his life. Though he managed to earn his doctorate (The Concept of Art Criticism in German Romanticism), summa cum laude, in 1919, he complained to Scholem that he had to “hack through” his courses, and the two friends, both based in Switzerland at the time, joked incessantly about establishing their own parody institution, the University of Muri. In the mid-1920s Benjamin confided to Scholem that the theoretical introduction to his postdoctoral thesis, on the origin of German tragic drama (his halfhearted attempt to launch an academic career), was an act of “unmitigated chutzpah.” Benjamin never warmed up to the idea of being attached to a single institution, academic or otherwise, and scholarly specialization was generally anathema to an intellect as omnivorous as his.

The remainder of Benjamin’s life was an intellectual odyssey, and Leslie does a fine job of charting it, from the competing currents of thought running from Marxism to Messianism, the pressures of Brecht, Adorno and Scholem, and the perennial difficulties of eking out a living as a freelancer. Leslie is equally adept at examining Benjamin’s many loves (the youth activist Grete Radt; the already married Dora Pollack, née Kellner, whom he would go on to marry, have a child with and later divorce; the Latvian Bolshevik Asja Lacis; and the Dutch painter Anna Maria Blaupot ten Cate) and at showing his enormous range of creative interests and ambitions–he once expressed his firm hope to ennoble his profession, to “create criticism as a genre” unto itself–and his far less impressive ability to support himself and his family. Leslie lays bare the vast extent of Benjamin’s agonizing dependence on the largesse of his parents, his in-laws, friends and colleagues.

In the second half of Leslie’s book, the story of Benjamin’s life takes something of a plunge. After his messy divorce from Dora, Benjamin sells off his prized collection of children’s books. He bounces around, living as a frequent houseguest of friends and taking on assignments, in addition to his more high-minded pursuits, merely for a commission. His health begins to decline, he fears that his ideas are being filched by his friends Ernst Bloch and Siegfried Kracauer, and he frets that his chances of fleeing occupied France, whether to Palestine or to the United States, are becoming increasingly slim. “With no way out,” he would ultimately go on to explain in his last communiqué, “I have no other choice but to end it. It is in a little village in the Pyrenees where no one knows me that my life reaches its conclusion.”

Leslie’s biography concludes with a provocative discussion of Benjamin’s afterlife–the ways he has been remembered since his tragic death in late September 1940. Benjamin, who had secured a US visa through the aid of his friend Max Horkheimer, died in the border town of Port Bou after the group of refugees with whom he had crossed the Pyrenees was denied entry into Spain. In addition to several highly inventive conspiracy theories–that Stalinist agents might have been responsible for Benjamin’s death, as one critic has it; or, as David Mauas’s 2005 documentary Who Killed Walter Benjamin? suggests, perhaps it was a group of local Falangists–there have been countless works of homage, from novels and plays to paintings and films, and other, more monumental forms of memorialization. Israeli sculptor Dani Karavan’s Passagen, erected just outside the Port Bou cemetery in 1994, stands as arguably the most poignant testament to Benjamin. Built of steel and glass, the enclosed structure stretches from the jagged cliffs to the surf below. This passageway has a vertiginous effect on the viewer, who is led down a long flight of stairs to a sheet of glass etched with words taken from among Benjamin’s last lines: “It is more arduous to honor the memory of the nameless than that of the renowned. Historical construction is devoted to the memory of the nameless.”

Benjamin is no longer nameless. In fact, not unlike other precious reliquaries, his writings have in recent years become the celebrated subject of public art exhibitions in their own right. This past summer, from May through the end of August, the Museum of Modern Literature in Marbach, Germany, organized a show around the original manuscript of Benjamin’s Berlin Childhood Around 1900, and in the autumn of 2006 the Berlin Academy of the Arts hosted a large-scale exhibition of the Benjamin archive–culled from some 12,000 pages of text it has in its holdings. The exhibition catalog was published that same year, and thanks to Leslie’s work as translator, the book is now available in English as Walter Benjamin’s Archive. In certain respects, the volume is a fitting tribute to a thinker who was very much an archivist himself: a man who preserved his correspondence, kept copies of manuscripts (his own and those written by friends), diaries, notebooks, drafts, drawings, outlines and other miscellany, and who offered unremitting reflections, theoretical and personal, on the significance of collecting. The book’s thirteen chapters–more “convolutes,” in the spirit of his Arcades Project, than discrete, entirely independent sections–encompass sketches and marginalia, poems and bons mots, postcards and snapshots, and many, many brown-tinted facsimiles of Benjamin’s compressed, diminutive, almost illegible handwriting; Benjamin once told Scholem of his wish to fit “a hundred lines onto an ordinary sheet of notepaper.” In another respect, Walter Benjamin’s Archive is the most recent incarnation of the trend among Benjaminiacs of publishing facsimile editions that treat their idol’s original manuscripts as repositories of some talismanic quality. Yet in his “Work of Art” essay, Benjamin himself states rather unambiguously, “There is no facsimile of the aura.”

Among the more revealing items reproduced in Walter Benjamin’s Archive is a scrap of paper–probably a restaurant bill–with the S. Pellegrino mineral water trademark stamped on it. Below the Pellegrino bottle icon, Benjamin wrote, “What is Aura?” In the right-hand corner he has scribbled a note, the beginning of a poem, perhaps, or maybe just a few stray thoughts that came to him in an intoxicated state: “Eyes staring at one’s back/Meeting of glances/Glance up, answering a glance.” This may not be the key to unlocking the secrets of Benjamin’s concept of aura (in the body of the text, jotted on the Pellegrino paper, he avers, equally cryptically: “Aura is the appearance of a distance however close it might be”), but it does offer insight into the Verschachtelung, or interlocking nature, of his thought, as if all his ideas emerged from a pile of scrap paper.

As a graduate student in the early 1990s, I remember seeing what I took to be unmoored philosophy students from the late 1960s and ’70s still toiling away on their dissertations at Berkeley’s Café Mediterranean on Telegraph Avenue, with bundles of dog-eared file cards bound with thick rubber bands and stacks of yellowed paperbacks lined up on their tables. Had Benjamin ever made his way to Lisbon and on to New York City–and maybe to the West Coast, where his friends Brecht, Adorno and Horkheimer had all taken up residence by the early 1940s–perhaps he would have become one of these cafe dwellers. In a letter of April 1934 to his friend the critic and theologian Karl Thieme, Benjamin wrote with a sense of despair regarding the chances of ever having his work published or reaching an audience of any size.

For someone whose writings are as dispersed as mine, and for whom the conditions of the day no longer allow the illusion that they will be gathered together again one day, it is a genuine acknowledgement to hear of a reader here and there, who has been able to make himself at home in my scraps of writings, in one way or another.

During his final years, when forced to write under a pseudonym, one of the names Benjamin chose was O.E. Tal, an inversion of the Latin lateo, “I am hidden.” Some seven decades and countless editions later, he is hidden no more.