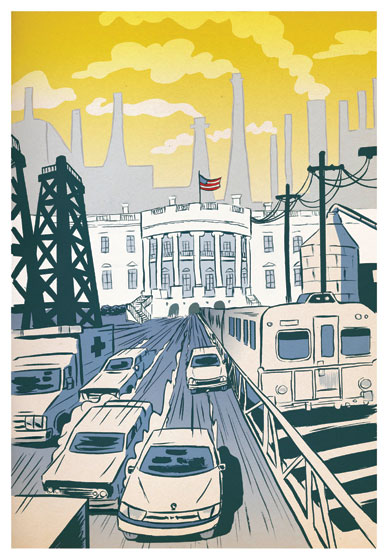

RYAN INZANA

RYAN INZANA

John McCain’s desperate attempts to smear Obama as a socialist during the last weeks of the campaign because of his defense of progressive income taxes are well behind us. Now that Obama’s economic team has been named, primarily from the center-right, the question is more likely to be whether he is still a left-wing Democrat. But the attacks were a sign of how far right the Republicans had gone in questioning a policy long accepted by most Americans. We have forgotten that under that notorious left-winger Dwight D. Eisenhower, the tax on the highest bracket was 90 percent. In recent years tax cuts have been used, very effectively, to redistribute income upward. But “socialist” seemed to work as an epithet, replacing “communist,” no longer useful now that Russia and China have become capitalist, and “liberal,” now overused.

While Socialist parties still play an important role in Western Europe and, increasingly, in Latin America, they have long disappeared from the American scene. Since the death of Michael Harrington, there has been no acknowledged spokesman. Though Bernie Sanders was elected as a socialist, he has not chosen to forward any socialist alternatives. There is no one around to explain what socialist approaches to the present economic crisis might be, what a platform different from Obama’s very careful centrist arguments would be like.

In 1942 a quarter of the population thought that socialism, of the kind that would be elected in nearly all of Western Europe, would be a “good thing.” Socialist ideas were so popular that Harry Truman, old-style Democratic machine politician that he was, ran on a platform well to the left of Obama’s–or of any of his Democratic successors. He faced important competitors to his left, not only the Socialist Party’s Norman Thomas but also the more popular Progressive Party candidate, Henry Wallace. Truman thus argued for a socialized national health insurance plan, for more TVAs as well as more public housing, hospitals and the like. Full employment, not tax cuts, was then the American priority.

To be sure, socialists, like the Democrats, have long argued for greater equality, economic as well as social. One can still see the effects of their policies in the Scandinavian countries and in France, where, despite having elected the conservative Nicolas Sarkozy, the top fifth of the population earns around four times what the bottom fifth does (as opposed to the United States, where the top 1 percent notoriously gets 20 percent of the national income). The French, along with the pre-Blair British and others, use their tax dollars in part to guarantee every citizen full medical care as well as an effective and free educational system through the university level. These extensive social payments, which all Socialist parties have implemented throughout Western Europe, give their citizens a far higher overall standard of living than we can hope to have.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

But socialists have traditionally argued for more than the welfare state. In order to guarantee equitable distribution, they have urged public ownership of crucial parts of the economy. Natural resources have been a major argument here, with oil and gas being obvious candidates for public ownership, since no individual capitalist has been responsible for their creation. Ironically, this is the case in Alaska, where those resources are publicly owned, as Governor Sarah Palin has boasted, allowing her to send substantial annual checks to each of her constituents. The checks would be larger if the oil companies were also publicly owned, as they are in many countries.

Public ownership is not an all-inclusive dogma but one that has been applied pragmatically. In postwar Britain, the coal mines, the steel mills and the railways were nationalized, in part to provide the necessary funding to keep them running (as, in effect, happened here with Amtrak). When Margaret Thatcher’s government began to privatize some of these industries, the results were shocking even to conservatives. Rail prices skyrocketed and accidents became so common that the British have begun to rue their decisions. When water was privatized, prices rose to incredible heights while the heads of the new companies paid themselves millions, showing how easily the private sector can redistribute wealth from the many to the lucky few.

France nationalized its banks after the war and again under the Socialist François Mitterrand, to allow it to direct loans into socially useful areas. We have seen, in recent weeks, the international success of Gordon Brown’s approach to a true nationalization of British banks. Remembering his socialist background, Brown opted for true control, rather than giving the bigger banks vast amounts with which to buy their competitors and continue to pay dividends, as has happened with Henry Paulson’s “socialization” of the banks. Reversing those decisions should be on Obama’s agenda. Using Brown’s approach, the $20 billion just paid to Citigroup would have sufficed to buy the whole company, at the price the stock had fallen to, instead of settling for a symbolic 7.8 percent share of the equity. It might have been interesting to see what could be done with a bank that was committed to lending rather than gambling.

Over the years, European automobile companies have also been nationalized, like Renault in France and Volkswagen in Germany, allowing them to compete, for decades, with the private sector and giving their workers a share in the management, as is still the case in many of Germany’s industries. (To my amazement, Hardball host Chris Matthews discussed the possibility of nationalizing the Big Three auto firms the other night. When questioned about this, GM’s president and chief operating officer Frederick Henderson gave a one-sentence lie, saying he was familiar with the European experiments and that they had failed.) The European auto companies were so successful that conservatives argued they should be privatized, which put them at greater risk competing against the cheaper car makers of Eastern Europe and Asia. An autoworker in Slovakia, for example, makes a quarter as much as his French or German counterpart, which has caused an increasing movement of jobs to the countries paying lower wages. Were these companies and others still publicly owned, they could choose lower profits over sending their work overseas. France recently imposed large fines on profitable private firms that chose to close their factories in France to increase their profits even more. Most of the French agree that keeping jobs and decent wages going is a basic responsibility of industry, private or public. With the growing protectionist sentiment in the United States, such an approach might prove very popular. Obama has talked about renegotiating NAFTA, but these constraints on the private sector might also be considered.

In addition to such measures, a strong case could be made for the public ownership of industries that depend overwhelmingly on American government purchases and on subsidized research. The military is clearly in that category, as is the pharmaceutical industry. The ever increasing cost of Medicare is clearly linked to the outrageous markups by pharmaceutical firms that have often received government money to develop their products while refusing to seek cures for illnesses that are insufficiently profitable. In addition to capping prices, the government could buy a controlling interest in shares. Once it became clear that the government as stockholder would give priority to the rights of consumers, the price of shares would diminish considerably. This would probably save us all a great deal of money in the long run. Such a case for public ownership might even win popular support.

Socialists have long realized that if government is unable to control big business, businesses will control the government and its regulators, as has happened so flagrantly in recent years. In difficult times, it is all the more important, as we have seen in the banking crisis, that those controlling the financial industry not use the government simply to bail themselves out but to help the overall economy. Those arguing for unregulated private ownership, with ever increasing profits as their only goal, have come close to ruining the very economy they had so long controlled. The Friedmanite myth of the perfect market lies in ruins. It is clear that more and more people, here and abroad, are looking for new alternatives. As the global crisis continues, more of us, not just Obama, may want to begin to consider some of these socialist solutions. Everyone now remembers that Franklin Roosevelt initially ran on a very cautious, even conservative, platform. As he discovered, changing events may demand ideas that, until recently, seemed unthinkable.