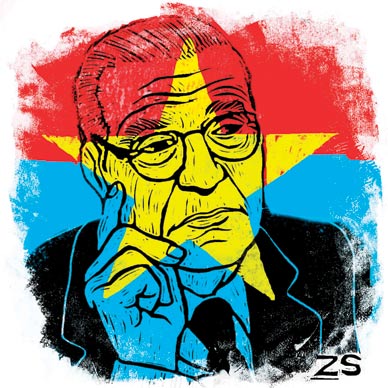

ZINA SAUNDERS

ZINA SAUNDERS

I first met Robert McNamara in the summer of 1967.

The meeting had been arranged by Jerome Weisner, then the provost of MIT. I had just returned from a trip to South Vietnam, where, as a reporter for The New Yorker, I had witnessed the substantial destruction by American air power of two provinces, Quang Ngai and Quang Tinh. Flying in the back seat of Forward Air Control planes–small Cessnas that coordinated the bombing and strafing runs by radio contact with ground forces and the bomber pilots–I measured the destruction that had already occurred and witnessed at first hand the destruction of villages as it transpired. The policies were clear. Leaflets dropped on villages had announced, “The Vietcong hide among innocent women and children in your villages…. If the Vietcong in this area use you or your village for this purpose, you can expect death from the sky.” Death from the sky came. After it had, more leaflets were dropped, saying, “Your village was bombed because you harbored Vietcong…. Your village will be bombed again if you harbor the Vietcong in any way.”

The results were also clear. As I could see from the air, in Quang Ngai province some 70 percent of the villages had been destroyed. All this, in one of the euphemisms that were the lingua franca of the Vietnam War, was called “the air war.” Actually, it was one-sided air slaughter, mostly of civilians. I was 23 years old at the time and had no notion what a war crime was; but it became clear to me later that that was what I had been witnessing, day after day. (Six months after I left, in March 1968, American troops committed the massacre at My Lai, in which some 350 people were killed.)

Weisner, a friend of McNamara’s, thought he should know what I had seen. The purpose of my meeting McNamara, which by agreement was to be held confidential, was to tell him. I didn’t know it, but his loss of faith in the war was already well under way, and that November he announced his departure from office to take up the presidency of the World Bank. The familiar figure with the glinting rimless glasses and the rigid hair forced back, as if it were spun glass, greeted me at the door of his seemingly tennis-court-size office overlooking the River Entrance of the Pentagon and, across the Potomac, the Washington Monument.

In the man I met, I felt a prodigious, ceaseless, restless energy that I suspected he could not turn off if he wanted to. Doing one thing, he seemed already to be thinking about the next, or the thing after that. At rest, he seemed to be moving more quickly than most people when running. As I began to recount my observations, he pinned me with a stare. My feeling was that he was not precisely a good listener but might, in his self-directed way, be a good absorber of information. He took me to a map of Vietnam on an easel at the back of his office and asked me to locate the areas of destruction. I felt that the request was a test–one I happened to be excellently prepared to take, as I had carried maps with me in the Forward Air Control planes and had measured levels of destruction in the entire province of Quang Ngai.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

McNamara seemed deeply engaged, but made no comment, asking me only if I had anything in writing. I said I did, but that it was in longhand. He suggested that I produce a typed copy, and provided me with the office just down the hall of a general who was away, if memory serves, in Africa. What McNamara did not know was that the article was book-length. It turned out to take three days to dictate the piece into the general’s Dictaphone, with chapter after chapter emerging handsomely typed from the bowels of the Pentagon.

I then handed the finished project to McNamara, who thanked me but said nothing further about the matter, either then or at any time thereafter.

Yet there was a sequel. Fifteen years later, in 1982, when Neil Sheehan was researching his classic book about the war, A Bright Shining Lie, he came across several documents concerning my Pentagon-assisted manuscript, and brought me copies. It appears from the documents that McNamara had promptly sent the manuscript to the US ambassador in South Vietnam, Ellsworth Bunker, who in turn ordered a certain Hataway to retrace my steps in Quang Ngai and Quang Tinh, and also requested a Bob Kelly to write an overall report, with a view to discrediting my reporting and arranging to get The Atlantic (where Bunker mistakenly thought it was scheduled to appear) to “withhold publication.” He circulated a memo recommending these things to McNamara, Under Secretary of State Nicholas Katzenbach and Assistant Secretary of State William Bundy. The “action” officer was Secretary of State Dean Rusk. Those I had interviewed, including the Forward Air Control pilots, were reinterviewed, and affidavits were taken from them. Two civilian pilots were dispatched to fly over the provinces and check my calculations of the damage. Plans were considered to publicly rebut my findings. However, the resulting report inconveniently found that “Mr. Schell’s estimates are substantially correct.” It appears that no further action was taken. In any case, McNamara announced his resignation as defense secretary around this time.

Perhaps frustrated by his failure to find factual errors in my reporting, the author of the report offered some editorial comments that inadvertently epitomized the flawed thinking on which the entire war rested. I had been unaware, he thought, of some extenuating factors regarding the destruction I had witnessed. I had not known, he thought, that “the population is totally hostile.” Indeed, in the eyes of the Vietcong, “the Viet Cong are the people.” Thus did one of the main reasons for not fighting the war in the first place–namely, the perfectly obvious hatred the majority of the population felt for the American invasion and occupation–become, in this calculation, a reason for continuing the war.

When I next spoke at length with McNamara, in 1998, it was not about Vietnam but about nuclear arms, on which we were agreed as much as we had disagreed about Vietnam: we both believed that the only decent and sensible thing to do with the bomb was to get rid of it. McNamara’s turnabout on the nuclear matter was dramatic. More than any other government official, he had been responsible for institutionalizing the prime strategic doctrine of the nuclear age, deterrence, otherwise known as mutual assured destruction. Now he wanted to dispense with it. He was table-poundingly intense in his conviction.

In fact, by then we were closer on Vietnam as well, for McNamara had, after two decades of silence regarding the war, published his book In Retrospect, in which he repudiated his former justifications for the war, famously writing of the Kennedy and Johnson administrations, “We were wrong, terribly wrong.” He had also revealed an emotional side under the titanium exterior. We know now that at his farewell meeting as defense secretary, McNamara wept as he acknowledged the uselessness of the bombing. Was he thinking of the devastated villages of Quang Ngai? I don’t know. On many occasions when confessing his errors regarding the war, his voice shook or cracked and tears came. Like a certain kind of man common in his generation, he was emotional without being introspective. The book was “retrospective,” not introspective–it was a public reflection on a public matter and contained almost nothing in the way of soul-searching. In its tone and style, the book, though it had to have been written out of a profound reservoir of feeling, reached for the stable ground of objective analysis.

Many critics have asserted–rightly, I think–that he stopped short of full understanding, that he sought to hold fast to claims of noble intentions that the record cannot sustain. The issue is how noble intentions really can be when when the facts that show their results turning to horror are readily at hand yet overlooked. Should McNamara have been more forthcoming in his regrets? He should. Should he have expressed them earlier? Certainly. Should he have resigned in protest once he understood that the war was futile and wrong? Yes. Should he never have recommended the war or presided over it in the first place, and should there never have been an American war in Vietnam? Oh, Lord, yes! Recent American history with that war subtracted? What a vision of a better country that was attainable but lost! Certainly, if one puts McNamara’s tears on one side of the scales and the deaths of some 3 million Vietnamese and 58,000 Americans on the other, there is no doubt which way the scales would tip.

On the other hand, how many public figures of his importance have ever expressed any regret for their mistakes and follies and crimes? As the decades of the twentieth century rolled by, the heaps of corpses towered, ever higher, up to the skies, and now they pile up again in the new century. But how many of those in high office who have made these things happen have ever said, “I made a mistake,” or “I was terribly wrong,” or shed a tear over their actions? I come up with one, Robert McNamara. I deduce that such acts of repentance are very hard to perform.

If a statue is ever made to him, as probably there will not be, let it show him weeping. It was the best of him.