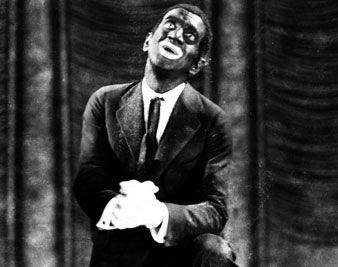

AP ImagesAl Jolson performs in blackface makeup in The Jazz Singer, 1927.

AP ImagesAl Jolson performs in blackface makeup in The Jazz Singer, 1927.

Hollywood’s first talking film marked the beginning of the end for some of cinema’s biggest stars with either squeaky voices or strong Brooklyn accents, but The Jazz Singer did preserve on celluloid the talent of Al Jolson and the remarkable voice of Judaism’s most famous cantor, Joseff Rosenblatt.

It is only a year since The Jazz Singer broke upon us, but the revolution occasioned by this sudden appearance of a talking movie-play has been as thorough as could possibly be imagined. The one regrettable result of the revolution has been the virtual disappearance of the silent picture from the bigger houses on Broadway. Thus the week beginning June 9 witnessed, among the Broadway first runs, fourteen talking pictures and only three silent ones. One need not share the sophomoric enthusiasm which has recently developed for the silent picture, or pay much attention to the confused and often ignorant theories with which this enthusiasm is usually buttressed, to feel distressed at the sight of this wholesale slaughter. It looks as if the silent picture as an entertainment for the masses were definitely facing extinction. A year or so until the picture houses are “wired” for sound in this country, a little longer perhaps in other parts of the world, and the only silent pictures left will be those especially intended for the small ranks of admirers of cinematic art. But, deploring this fact as we may, let us also remember that among the films made during the past twenty-five years one would be hard put to it to count an equal number of cinematic masterpieces (outside of Chaplin’s work, most, though by no means all, of which is certain to survive, thanks to Chaplin’s own genius as a performer). In a sense, therefore, one may welcome the present commercial eclipse of the silent picture as a means of its emancipation from Hollywood with the possibility of its renaissance on an entirely new aesthetic foundation. The technical improvements forecast by the talkies, such as the enlarged projection and effects of color and depth, are also sure to redound to the benefit of the silent picture whose means will thus be enriched for the conquest of forms of expression which are no less fascinating than the flat monochrome of the film of today. And now we may ask what progress has been made during the year of talkies. Judging by the opinions voiced in the press the progress must have been enormous. On closer examination, however, one finds that it is usually the fickle critic’s conversion to the talking picture that is announced as improvement of the pictures themselves.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

So far it is in the most important direction that one finds the least advancement. An absolutely faultless reproduction of human speech is obviously the first consideration in a talking picture. And yet today, as a year ago, we are still treated to hollow and squawking and lisping voices, and even to imperfect synchronization. To quote a few instances, in Coquette Mary Pickford’s voice was too painful to listen to (it would seem, women’s voices generally suffer more than men’s), and in Broadway one saw the flapping lips of the characters while the sound seemed to come from an entirely different direction. It is not for a layman to discuss frequencies, acoustics, and other technical matters, but it is clear that far from sufficient care is being taken to insure perfect reproduction in the theaters which is the only part of the process of direct and paramount interest to the audience. The very fact that in some pictures shown on Broadway the reproduction sounded wellnigh perfect (as in The Rainbow Man, for instance, which the present writer heard from a seat very close to the screen), while in other pictures it was almost unbearable, is proof positive that producers are too much in a hurry to display their product. In these mechanical matters, even at the present stage of their progress, there should be no such thing as taking potluck when one goes to a talking movie.

And how have the talkies fared as dramatic entertainment? When they appeared first those who were able to cast off old prejudices instantly saw that the thing worked—that it got its dramatic effects over as easily as the stage, and more easily than the silent picture—and this in spite of its obvious crudity. Today we still say that the thing works, though the crudity is only a little less obvious than it used to be. Unquestionably, there has been a noticeable advance in the general treatment of plays. Scenes run more smoothly into one another, acting is less stiff, and effects are increasingly more cinematic. The action in Bulldog Drummond is as swift and continuous as in any old Hollywood mystery drama. In Madame X Ruth Chatterton is the acme of naturalness. In The Trial of Mary Dugan the district attorney’s finger pointing at the accused, with his voice off-stage, and similar instances in other pictures, separating the voice from the image of its owner, provide examples of distinctively cinematic technique. Another instance of such technique is Broadway’s attempt to introduce a “fade-out” of sound. And yet stage models still govern the screen versions in their major parts. And for reasons which it is difficult to discern, the total effect of the talking picture is generally thin, lacking in substance. Strange as it may appear, a silent picture seems to be freighted with sensory appeal. A picture like The Last Laugh is a veritable “eye-full.” In the talkies, much as you may be moved by the drama, you feel it is a drama in a world of ghosts. Perhaps, the introduction of stereoscopic projection coupled with color will solve this problem.