What should be done if the Supreme Court strikes down the Affordable Care Act’s individual mandate?

If the Court does anything—which, of course, it should not—it would likely only remove the mandate and possibly the associated insurance company regulations and subsidies for purchasing insurance. Striking down the entire law would be a dramatic and unlikely step, even for this conservative bench.

So where would the law stand if the mandate disappears, and what could be done to patch it?

Many Democrats and their political allies have been publicly and privately talking up the benefits of the Affordable Care Act outside the mandate—like the Medicaid expansion, the ongoing creation of state exchanges for buying health insurance, the various cost-control measures in the bill—and downplaying the severity of losing it.

“There’s been entirely too much attention paid to the mandate, and not enough attention paid to what the law will do and the ways that it’s already benefiting millions and millions of Americans,” Ethan Rome, executive director of the progressive coalition Health Care for America Now, which was instrumental in getting the law passed, told me in a phone interview. “The sport of speculation about what the Court will do is in overdrive, and as part of that, people are overthinking how to make the law work if one thing or another about it is changed.”

Indeed, two studies—by the Rand Corporation and the Urban Institute—predict minimal disturbances in overall coverage and premium prices without a mandate.

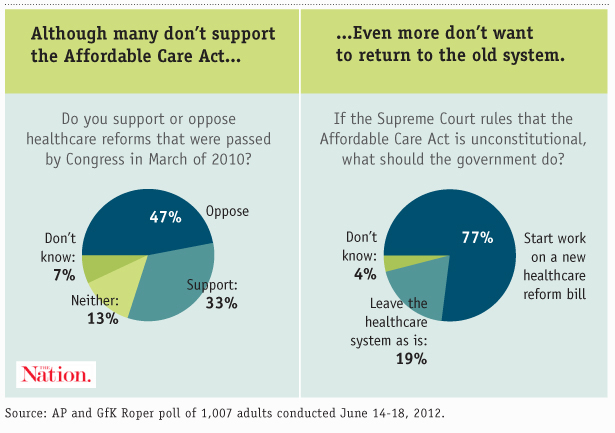

But there’s no doubt that if the Supreme Court indeed guts the mandate, it would create a political opportunity for more reform of the healthcare system. Seventy-seven percent of Americans want another reform attempt even if part of the law is struck down, and President Obama has been privately telling donors his administration would probably make another run at improving it. House minority leader Nancy Pelosi is on board too. And who really thinks that, even if it remains untouched, the Affordable Care Act represents the pinnacle of health reform?

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

Here’s a quick look at some policy options to move the ball forward on healthcare reform if the mandate is struck down:

Helping the uninsured to buy coverage. The idea behind a mandate was that by increasing the number of people buying insurance, it would lower the costs for everyone else—both by broadening the base of premium payments, and reducing the external costs of the uninsured seeking treatment in emergency rooms. More urgently, since the ACA required insurance companies to provide coverage to people with pre-existing conditions, it had to have a mechanism to ensure that people wouldn’t just wait until they got sick and then purchase insurance.

But if the mandate is gone and you can’t force people to buy coverage, there are several ways you might be able to entice them to do so:

Subsidies. In the House version of the Affordable Care Act, a surcharge on the wealthy would help fund subsidization of health insurance for people who couldn’t afford it. Annual household income in excess of $350,000 but less than $500,000 would be have a 1 percent surcharge attached; annual household income in excess of $500,000 and less than $1 million would have a 1.5 percent surcharge; and annual household income in excess of $1 million would have a 5.4 percent surcharge. Thursday on Capitol Hill, House minority leader Nancy Pelosi said that in the event the mandate is struck down, “there could be something passed in the Congress, similar to what we had originally in the House bill, which was a surcharge on the wealthy to pay for aspects of [coverage].”

Employer auto-enrollment. Under the ACA as it stands now, large employers (with 200 or more employees) must automatically enroll workers in a health insurance plan, though the workers can opt out if they want to. By making enrollment the default position, we can catch more young and healthy people who might decline to select a plan in the name of a bigger paycheck. One idea for further expanding coverage without a mandate is to extend auto-enrollment to smaller employers, and possibly even ones that don’t offer health insurance. In the words of the Government Accountability Office, this might further “overcome individuals’ inertia in choosing a plan.” If an employer doesn’t offer coverage, it would be forced to help an employee enroll in a plan through the state exchange markets. While it would no doubt help patch some holes left by the absence of a mandate, there’s an obvious problem to this solution—it affects only people with a job, and most people without health insurance are unemployed.

Age rating. The government could entice young and healthy people to buy coverage by allowing health insurers to charge them less, which is known as age rating. The ACA allows insurance companies to charge the elderly only a maximum of three times more than the young, but if that ratio were revised upward, it could make health insurance more attractive to the healthy. But the flipside is that it would necessarily make coverage for the elderly even more expensive, and as Ezra Klein notes, age rating hasn’t done much for affordability of coverage in New Jersey, where it’s been in place since 2008.

Penalties for not buying coverage. Aside from helping people buy coverage, you can penalize them for not doing so. That’s what the individual mandate does, instituting penalties ranging from $695 for poor Americans to $12,500 for wealthy ones for not obtaining health insurance. You can create penalties in other, smaller ways without a mandate—though we should note that these aren’t particularly progressive options. If you think of the uninsured as being all free-riders, then penalties make sense. But again, a majority of the uninsured are either too poor to afford insurance or don’t have a job that offers it, and are often both. So penalizing them further isn’t terribly helpful.

State-level mandates. If the Supreme Court rules that the federal government cannot mandate health insurance coverage, it doesn’t mean that individual states can’t do it. Many probably would, especially if the pre-existing condition regulations remain in place. Even Governor Scott Walker—a rabid opponent of “Obamacare”—said recently that he would explore “guaranteed issue” of health insurance in Wisconsin. “Certainly not a federal mandate,” Walker. “[But] I think those are debates people can have at the state level.”

Tax penalties for uncompensated care. If the federal government wasn’t allowed to institute a broad set of penalties for not buying coverage, it could create new taxes for going to an emergency room and receiving charity coverage without insurance. The GAO outlines a few ways to do this: by instituting the tax on everyone, but waiving it when an individual presents proof of insurance, or by taxing the uncompensated care directly. This would indeed make free-riders more likely to buy insurance, to avoid heavy tax penalties, but if you consider someone who lost their job and thus their health insurance, laying extra taxes on them after a heart attack really isn’t a wonderful policy.

Open enrollment periods. If you receive coverage through your employer, you’re probably familiar with these. Health insurance companies and employers will join together to offer periodic and finite enrollment periods for insurance of varying cost and coverage—the idea is to prevent people from picking the cheapest plan and then bumping up their coverage if they get sick. One approach to creating a soft mandate is to expand open enrollment periods—the ACA already institutes annual open enrollment, but some proposals advocate making open enrollment happen only every two years or even every five years to create even stronger incentives to get insurance. One could still buy coverage after open enrollment, but would face financial penalties for doing so. (Such proposals have exemptions for people with “qualifying life events,” i.e., becoming an adult, giving birth, changing jobs or getting a divorce).

Making health coverage part of your credit rating. This is contained in a GAO report outlining several post-mandate policy options dreamed up by a variety of experts, academics and industry officials. I’m only including it here to point out what an awful idea it is. The proposal is to essentially lower your credit score if you don’t have health insurance. Yes, it would probably bring some free riders into the insurance pools, but destroying the credit of unemployed people with no health insurance is terrible public policy. Another idea in the GAO report is to make possession of health insurance a condition for receiving certain government benefits, such as a federal college loan. This is terrible for the same reason.

Thinking progressively and outside the box. After considering how regressive penalties for not buying insurance can be, you might realize a dirty little Democratic secret, if you haven’t already: the individual mandate isn’t all that progressive. Yes, it makes the Affordable Care Act work better, and should be preserved. Yes, the Supreme Court would unmistakably enter into a new period of activist overreach if it strikes it down. But remember this was originally a Republican idea.

So what are some truly progressive alternatives to the mandate?

An obvious answer is single-payer health insurance. Former Labor Secretary Robert Reich wrote in March that if the Supreme Court strikes down the individual mandate but leaves the pre-existing condition requirement in place, “Obama and the Democrats should say they’re willing to remove that requirement—but only if Medicare is available to all, financed by payroll taxes.”

The political will for a single-payer system almost certainly doesn’t exist right now, however. (Though Democrats could start nudging towards it, for example by lowering the Medicare eligibility rate to 55).

In the meantime, the public option might be the best viable option for a progressive improvement of the healthcare system—and one that would seem much more attractive if the Supreme Court guts all or part of the ACA. More so than any of the aforementioned incentives, and more so than a punitive individual mandate, the public option would be extremely compelling for the uninsured, offering a lower cost and more protections than most private insurance plans.

In 2010, when it was clear the public option was dead in the Senate, President Obama promised progressives he would return to fight for it later on down the road. He should be held to that promise, particularly if a key part of his bill is struck down—and frankly, even if it isn’t.