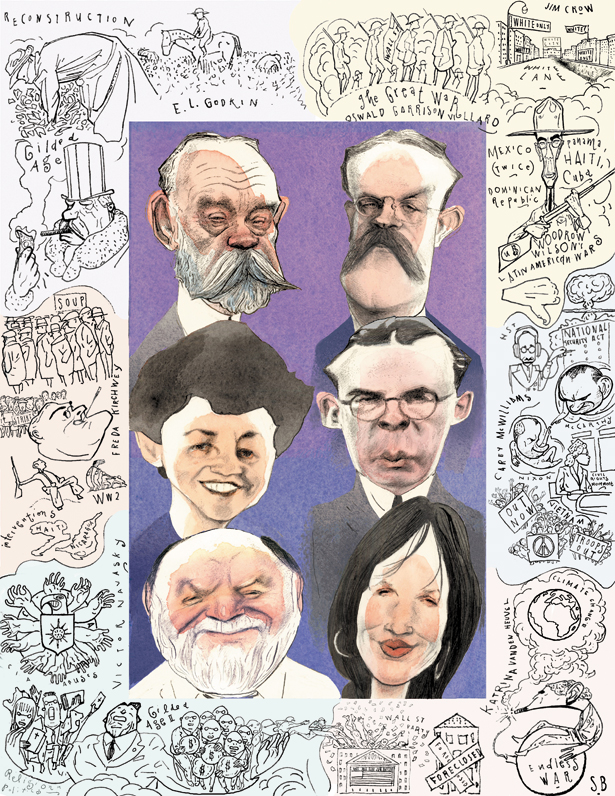

(Steve Brodner)

This article is part of The Nation’s 150th Anniversary Special Issue. Download a free PDF of the issue, with articles by James Baldwin, Barbara Ehrenreich, Toni Morrison, Howard Zinn and many more, here.

This article is part of The Nation’s 150th Anniversary Special Issue. Download a free PDF of the issue, with articles by James Baldwin, Barbara Ehrenreich, Toni Morrison, Howard Zinn and many more, here.

From The Nation’s very inception, the idea of freedom has been fundamental to its political outlook. Of course, freedom (along with its twin, liberty) has long occupied a central place in Americans’ political vocabulary. Yet despite—or perhaps because of—its ubiquity, freedom is an idea whose meaning is always contested, always in flux. The Nation’s 150-year history exemplifies how successive generations of reformers and radicals (themselves ever-changing categories) have thought about freedom and how the concept has expanded over time to include more and more Americans and more and more realms of life. Ideas central to The Nation’s understanding of freedom today—economic justice, civil liberties, anti-imperialism, political democracy, racial equality and personal autonomy—are deeply rooted in one or another era of the magazine’s past.

The Nation was born in July 1865, shortly after the end of the Civil War, a conflict that transformed the meaning of American freedom. The journal’s founders included prominent Northern abolitionists. In a country rhetorically dedicated to freedom but substantially grounded in slavery, the abolitionist movement pioneered the notion of freedom as a universal birthright, a truly human ideal. Principles such as birthright citizenship and equal protection under the law without regard to race, which would later become cornerstones of American freedom, were products of the antislavery crusade. Soon after The Nation came into existence, they were written into the Constitution. The magazine’s very name reflected a new identification, spawned by the war, of the American nation-state with the progress of freedom. Thanks to the abolition of slavery, a powerful federal government, once widely feared as a danger to individual liberty, now appeared, in the words of the abolitionist Senator Charles Sumner, as the “custodian of freedom.”

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

The Nation’s primary audience was the reform-minded Northern middle class, solidly committed to the classic principles of nineteenth-century Anglo-American liberalism—not only antislavery, but also free trade, free public education, civil-service reform and an absence of governmental restraints on individual liberty. The editor, the Anglo-Irish journalist E.L. Godkin, who determined the magazine’s course until the turn of the century, never wavered from these beliefs. Increasingly, however, as American society changed, these views made him more and more conservative. The Nation’s first issue proclaimed that the Civil War marked a momentous turning point in “the great strife between the few and the many, between privilege and equality, between law and power.” But as time went on, Godkin positioned the magazine on the side of the few, of privilege and of power.

The first indication of this transition was The Nation’s abandonment of the cause of the former slaves. The Nation’s prospectus listed among its priorities the “removal of all artificial distinctions” between blacks and the rest of society. Yet while Godkin initially supported granting the right to vote to male former slaves, he quickly succumbed to white-supremacist propaganda that depicted biracial Reconstruction governments in the South as travesties of democracy. He became persuaded that the former slaves were unfit for political participation. By the 1880s and 1890s, all semblance of compassion for African-Americans had disappeared from The Nation’s pages. Godkin expressed sympathy for Southern efforts to disenfranchise black voters, supporting poll taxes and literacy tests for voting “if honestly enforced” in a nonracial manner, which, of course, they were not.

Godkin was equally alarmed by the rise of a militant labor movement in the North and its demand for laws limiting the hours of labor. Increasingly, The Nation saw the democratic state itself as a threat to individual liberty. Godkin insisted that the market, not politics, was the true realm of freedom, which he defined as “the liberty to buy and sell…where, when, and how we please,” without government interference. Efforts to use the state to uplift the less fortunate were doomed to failure. Those at the top of society deserved to be there, since they were, by definition, the fittest. This was the language of Social Darwinism, whose leading American proponent, William Graham Sumner, became a Nation contributor.

By the 1890s, The Nation, created by one generation of reformers, was out of touch with the next—social thinkers critical of laissez-faire dogma and sympathetic to organized labor. As the economist Henry Carter Adams observed in 1894, “The New York Nation is a decided Bourbon. Its editors have learned nothing during the last twenty-five years.” Adams spoke for the “new liberalism” that emerged on both sides of the Atlantic in the late nineteenth century and flourished during the Progressive era, when reformers demanded greater governmental regulation of the economy and a more positive and collective definition of freedom. The Nation had little to say on these subjects. In the early twentieth century, its editor, Paul Elmer More, an erudite literary critic who had studied Sanskrit, Greek and Latin at Harvard, offered cautious support to some progressive legislation, such as the income tax (which Godkin had vehemently opposed), but focused the magazine on literary commentary rather than politics.

In the Progressive era, the revitalized labor movement insisted that in an age of corporate capitalism and widespread inequality, the concept of economic freedom needed redefinition. Progressive reformers argued that in a modern economy, “industrial freedom” for ordinary Americans meant not so much property ownership as economic security. To achieve this, laissez-faire was inadequate. Freedom required the ability of workers to organize collectively to advance their interests, and government action to create an economic floor beneath which no citizen would be allowed to sink. Such thinking remained alien to The Nation, which insisted in 1910 that “Any scheme of regulation which would prevent poverty would be equally subversive of liberty.” It was left to The New Republic, founded in 1914, to become Progressivism’s leading journalistic voice.

* * *

In one realm, The Nation under More did break with Godkin’s legacy. The latter had been skeptical of the ability of immigrants to take part in American democracy. In keeping with enlightened Progressive thought, however, The Nation repudiated the nativist upsurge sparked by the era’s immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe. In 1915, it carried Horace Kallen’s essay “Democracy Versus the Melting-Pot,” which rejected the idea of forced assimilation in favor of cultural pluralism.

The real break with The Nation’s past, however, came in 1918, when Oswald Garrison Villard—who had inherited ownership of the magazine in 1900 from his father, the railroad magnate Henry Villard—took over as editor, a position he occupied until 1932. He made The Nation livelier, more controversial and more radical. It quickly became what it has remained ever since: a voice demanding far-reaching social change in the name of greater freedom. Villard emphatically rejected the magazine’s traditional commitment to government nonintervention as the essence of liberty. The “widest possible freedom,” he wrote, required “social control in the common interest.” The Nation called on the “friends of freedom” to embrace the revolutions that swept Europe in the wake of World War I, defended labor’s right to organize, and advocated the “democratization of industry.”

If Villard brought The Nation to a belated embrace of Progressivism in economic policy, the magazine also embraced two stances, neglected by most Progressive reformers, that would become central to liberalism later in the twentieth century. One was racial equality. A grandson of the abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison and a founder of the NAACP, Villard viewed racial justice as essential to the fulfillment of the promise of American democracy. He revived The Nation’s original commitment to eradicating inequality for blacks. Villard voted for Woodrow Wilson in 1912 but quickly denounced Wilson’s segregationist racial policies. The Nation consistently spoke out against lynching and supported efforts to secure a federal law criminalizing the practice.

Villard’s other preoccupation was civil liberties. Most Progressives, entranced by the ways the democratic state could promote the public good, had evinced little interest in the rights of dissenters; the battle for free speech had been led by marginal groups like “free love” advocates and the Industrial Workers of the World. But massive repression during World War I gave birth to a new recognition of the importance of civil liberties. In 1918, The Nation itself saw an issue banned from the mails, for the curious reason that it criticized the government’s choice of Samuel Gompers to represent American labor at a conference in Europe (Gompers being far too close to the Wilson administration for Villard’s taste). The following year, an editorial on freedom of speech proclaimed that “it is the men who are denying that right, and not the Socialists and I. W. W.’s, who are the most dangerous enemies of the social order to-day.”

In 1923, under the heading “Sweet Land of Liberty,” The Nation detailed the degradation of American freedom: the refusal to allow two socialists to speak in Pennsylvania, the arrest of 400 IWW members in California, the beating by Columbia University students of a graduate student who had written a letter to the university’s daily newspaper defending freedom of speech and the press. From World War I to the present, The Nation has identified freedom of expression as an essential hallmark of American freedom, and has highlighted and condemned violations of this principle.

In addition, thanks to Freda Kirchwey, who joined the staff in 1918, the magazine during the 1920s published pioneering articles on sexual freedom, birth control, divorce laws and the sexual double standard. It thus anticipated the more recent extension of the claims of freedom from a set of public entitlements into the arenas of family life, social and sexual relations, and gender roles. Overall, wrote the journalist Heywood Broun, “a curious piece of casting” had made Villard, the son of a robber baron, “head…of the most effective rebel periodical in America.”

* * *

In 1932, Villard retired as editor; Kirchwey soon succeeded him. The Nation quickly emerged as a strong supporter of the New Deal; if it criticized FDR, it was because it felt his response to the Depression was inadequate, not least in the area of racial justice. But it continued to insist that government power was crucial to the enjoyment of individual freedom. During World War II, The Nation enthusiastically embraced the idea of national economic planning to guarantee a “high-income, full-employment economy,” the only way to enable Americans to enjoy “the way of life of free men.”

Throughout Roosevelt’s presidency, The Nation was a combatant in the struggle over the idea of freedom. When opponents of the New Deal in 1934 created the American Liberty League, The Nation editorialized: “we are, of course, under no illusion as to what these eminent men have in mind when they use the word ‘liberty.’… [Their] conception of liberty is the right to maintain the old discredited order…the liberty of some men through special privilege and government favoritism, or by the absence of government control, to build up large fortunes.”

In international affairs, Kirchwey broke decisively with a tradition shared by all her predecessors—opposition to American military interventions overseas. Godkin strongly opposed the Spanish-American War on the grounds that an imperial state would inevitably trample on individual liberty, and that the peoples of Cuba and the Philippines were unfit for participation in American democracy. Unlike most Progressives, who managed to find a way to support American entry into World War I, Villard, a committed pacifist, never became reconciled to it. In the 1920s, The Nation strongly criticized the American occupations of Haiti and Nicaragua. During the following decade, however, Kirchwey increasingly viewed the rise of fascism as the major threat to freedom in the world and called for collective action to combat it. In 1941, she joined the Free World Association, which urged the United States to enter the war against Hitler.

The World War II discourse of a world divided into free and unfree sectors, which originated in the antifascist crusade, took on a new meaning during the Cold War. Under Kirchwey, who remained editor until 1955, and her successor Carey McWilliams, The Nation became perhaps the leading journalistic voice opposing American foreign policy and defending the right of dissenters against the onslaught of McCarthyism. In 1952, the magazine devoted an entire issue to the question “How Free Is Free?” The articles outlined the depredations of the “American witch hunt,” with its blacklisting, censorship, government loyalty programs and violations of academic freedom. The magazine published writings by Edgar Snow, Owen Lattimore and other targets of “Tail-Gunner Joe” McCarthy.

McWilliams had witnessed the impact of anticommunism firsthand in California, where he began his journalistic career. California, he wrote, “has probably had more witch hunts and more free-speech fights than any state in the union.” The experience left him with “an abiding contempt for professional ‘anti-Communists.’” While the “back” of the magazine contained literary and cultural pieces severely critical of Stalin’s Russia, both Kirchwey and McWilliams felt that to couple a critique of McCarthyism with accounts of the situation in the Soviet Union would deflect attention from the threat to freedom at home. The Nation insisted that communists deserved precisely the same civil liberties as other Americans, and when the ACLU refused to defend their rights, McWilliams helped form the Emergency Civil Liberties Committee to do so. His stance led to angry rebuttals from many liberals who coupled aggressive anticommunism with their criticisms of McCarthy. Magazines such as Commentary (which had not yet embarked on the path to extreme conservatism) and The New Leader carried on a vendetta against The Nation, charging it with “Stalinism.” Despite this, at a time when many journalists enlisted in the anticommunist crusade, The Nation remained the most outspoken champion of the right to dissent.

McWilliams continued to criticize American foreign policy. He published prescient articles by Bernard Fall about Vietnam and, in 1965, a piece by the historian Eric Hobsbawm on how the United States could not possibly win the war there. But McWilliams lacked Kirchwey’s preoccupation with world affairs and focused more on domestic concerns. He published exposés on the link between cigarette smoking and cancer, automobile safety (by a young law student, Ralph Nader), the rise of the military-industrial complex, and the illegal activities of the FBI and CIA.

As McWilliams later wrote, however, his “special interests” were civil liberties, organized labor and race relations. Beginning in the mid-1950s, the magazine devoted increasing attention to the civil-rights revolution, then gathering momentum. In 1956, nearly a century after The Nation’s founding, the magazine returned to its roots with a special report on race that began with a call for the federal government to “Enforce the Constitution.” The Nation fully embraced the militant phase of the civil-rights movement unleashed by the sit-ins of 1960. In 1962, it published an article by the civil-rights attorney Loren Miller that castigated white liberals for preferring incremental gains and ignoring the urgency of change. Blacks “don’t want progress,” Miller wrote, “they demand Freedom…Freedom Now.”

Here was the insistent voice of the ’60s, soon to be adopted in a host of campaigns by other groups that felt they did not enjoy full American freedom. Under McWilliams, The Nation viewed these new movements with a kind of sympathetic detachment. Most of its employees were over 40, and the cool, aloof McWilliams could not have been more different in demeanor from the decade’s insurgent youth. But almost in spite of itself, as a result of what the journalist Jack Newfield called McWilliams’s “intransigent radicalism” on civil rights, civil liberties and the Vietnam War, The Nation became a voice of ’60s protest. And McWilliams’s own longstanding example helped to inspire practitioners of the decade’s engaged, radical journalism.

* * *

McWilliams left the editorship in 1975. Victor Navasky and, subsequently, Katrina vanden Heuvel succeeded him. Their leadership has coincided with the triumph in American political discourse of a definition of freedom reminiscent in many ways of E.L. Godkin’s. Propagated most effectively by Ronald Reagan, it emphasizes limits on government as the essence of liberty; equates economic freedom with “free enterprise,” not economic security; and sees the unregulated economic marketplace as the true realm of freedom. (Unlike Godkin’s outlook, however, it is coupled with an imperial foreign policy.)

But The Nation has refused to cede the idea of freedom to the right. Drawing upon its complex history, it has articulated a different understanding of freedom, still grounded in a powerful commitment to personal liberty, and wary of overseas military interventions, but also fully engaged with the strivings for equality of disadvantaged groups of Americans—and rooted in a belief in the vitality of political democracy. Under Navasky, a First Amendment absolutist, The Nation maintained a commitment to freedom of speech and the press as cornerstones of American liberty, while extending the principle more than ever before to its own pages, which now included candid appraisals of past failures of the left. All sorts of competing viewpoints within the worlds of liberalism and radicalism clashed in the magazine’s pages (sometimes it seemed that columnists were most energized by criticizing one another). And The Nation now fully embraced the “liberation” movements spawned by the 1960s—the second wave of feminism and demands for equality by Latinos, Native Americans, gays and others—as well as issues the left had traditionally ignored, such as environmentalism.

In the twenty-first century, with vanden Heuvel as editor, The Nation has displayed considerable courage by standing virtually alone among significant media outlets in opposing the rush to war in Iraq (and, more recently, Syria). Especially since the terrorist attacks of 2001, moreover, The Nation has been at the forefront of protests against the curtailment, in the name of fighting “terrorism,” of legal protections such as habeas corpus, trial by an impartial jury, and limits on the government’s power to spy on individuals. It has challenged the invocation of freedom as an excuse for war overseas (George W. Bush’s Operation Iraqi Freedom, for example), and as a justification for the increasing dominance of big money in politics. And since the financial crisis of 2008, it has insistently raised the question of whether rising economic inequality and insecurity are compatible with genuine freedom.

History never really repeats itself. But the questions that preoccupied The Nation over the course of its history remain eerily relevant today. Will the onward march of capitalism produce a shared abundance—or a continued widening of the gap between the social classes? Will democratic self-government survive the assault of money and the transfer of economic decision-making to institutions such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, which lack any semblance of democratic legitimacy? Will the growing racial and ethnic diversity of American society promote greater tolerance, or fragmentation and bitterness? Will the ongoing revolution in the status of women, which propelled the idea of freedom into the most intimate realms of life, survive a powerful backlash? Can civil liberties co-exist with a “war on terror” that has no discernible ending point? These are the questions that will shape the life of the nation, and The Nation, in the years to come. In the twenty-first century, the need for a positive, expansive, socially responsible understanding of freedom is as great as at any time in The Nation’s history.

Eric Foner, Dewitt Clinton Professor of History at Columbia University, has been a contributor to The Nation since 1977—his first article was about Sacco and Vanzetti—and on the editorial board since 1996. His latest book is Gateway to Freedom: The Hidden History of the Underground Railroad, published in January.