In April 2003, Boris Johnson stood, awestruck, in Baghdad, staring into the remnants of a house blown apart by an American bomb. He was in Iraq on a fact-finding mission: He had voted for the invasion in his capacity as a Conservative Party lawmaker and was there to check out the aftermath. He was also working there as a journalist, documenting his experience in the British weekly The Spectator.

“Crumbs,” he recalls thinking as he surveyed the scene. “Crumbs” is an affected British expression meaning “gosh.” It also referred to the fragments left of the house; Johnson explained the wordplay, in case we didn’t get it. The ruins, he went on, were a neat metaphor for what the United States had done to the Iraqi regime, as well as the broader “range and irresistibility of America.” The “liberated” Iraqis he saw in Baghdad “were skinny and dark, badly dressed and fed.” The Americans “were taller and squarer than the indigenous people, with heavier chins and better dentition,” resembling “a master race from outer space, or something from the pages of Judge Dredd.”

These days, Johnson has made himself known as an opportunistic charlatan who campaigned for Brexit in order to become prime minister, became prime minister, then embarked on a reckless bid to throw the United Kingdom out of the European Union. Because of his bald careerism, his critics characterize him as a vacuum of beliefs—a black hole into which principles disappear. But one narrative has come up consistently in his writings and public statements over the years: Johnson is in genuine awe of the raw global power of the United States.

America, he has said, is the “greatest country on earth” and the United Kingdom’s “closest ally.” The United States’ rise he sees as the great story of the past century, upholding the idea that “government of the people, by the people, for the people should not perish from the earth.” For Johnson, American culture is a unifying, binding force that other pretenders to superpower status (China, Europe) lack. He has written of the thrill of flying in an American fighter jet, of strolling the Santa Monica Pier in California at sunset, and of the consummate Americanism of the film Avatar. Johnson also seems to believe the United Kingdom is in America’s league and should be treated that way. That view may well complicate efforts to negotiate a post-Brexit trade deal, but it doesn’t undermine his clear belief in a strong US-UK relationship.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

“Boris does, from time to time, fly by the seat of his pants, as we all know. He also contradicts himself quite frequently,” Robin Renwick, a former British ambassador to the United States, told me recently. “But he is a true believer in the specially close relationship with the US and the need to reinforce it.”

Johnson’s views on the United States are newly relevant. Whatever the outcome of his Brexit, he will need America to buoy his country’s economy and help the United Kingdom maintain political relevance on the world stage. But particularly with Trump in charge, that means taking orders from the Americans, and for all the surface comparisons between Johnson and Trump—the hair, the lying, the hair again—Trump does not fit Johnson’s stated views of what a president should be.

In the past, Johnson was harshly critical of Trump and his politics. In 2015 he called Trump “out of his mind” and “frankly unfit to hold the office of president of the United States.” Publicly, at least, Trump seems to have forgiven him, but Johnson already lacks leverage, and the power imbalance between the two countries will only grow in the likely chance of a messy Brexit. In such circumstances, will Johnson resist Trump’s bullying in order to protect his waning dignity and in the process threaten to sink the UK further into an economic hole? Or will he muster the humility to negotiate what he has always seemed to want—an even closer US-UK relationship—but accept whatever unpalatable conditions Trump insists should be part of the deal?

Historically, many Brits (including Johnson) have reacted poorly to the idea of the United Kingdom as a vassal or 51st US state. The Iraq-era epithet that stuck so ruinously to Tony Blair—that he was America’s poodle—will no doubt loom in Johnson’s mind.

As Johnson frequently reminds us, Brexit is about reclaiming sovereignty. Perhaps the question now should be, “From whom?”

Johnson’s love affair with the United States began early. He is a natural-born American and a native of New York City, where his father, Stanley Johnson, was a student in 1964. In a radio program later that year, Stanley Johnson said that friends of his then-wife, Charlotte Johnson, implored her not to have Boris in America, fearing the medical costs and the possibility of his conscription to serve in the military. The first of her fears, at least, was well founded, but it did not materialize. Boris was born at a pay-what-you-can clinic that “respectable” New Yorkers did not frequent, his father said. “We were neither respectable nor New Yorkers.”

Boris spent the first months of his life in a loft opposite the Chelsea Hotel. After an interlude back in the UK, Stanley Johnson got a job with the World Bank in Washington, DC, and was fired after he submitted a prank funding application to build pyramids and a sphinx in Egypt.

In 1969, when Boris was four, the Johnsons left the States again for England. Although Boris continued to have a cosmopolitan, itinerant upbringing—his family was based in Brussels for a time—he never again lived in America. “He did have important early years in America, though how much he remembers about them I can’t possibly tell you,” Stanley Johnson told me.

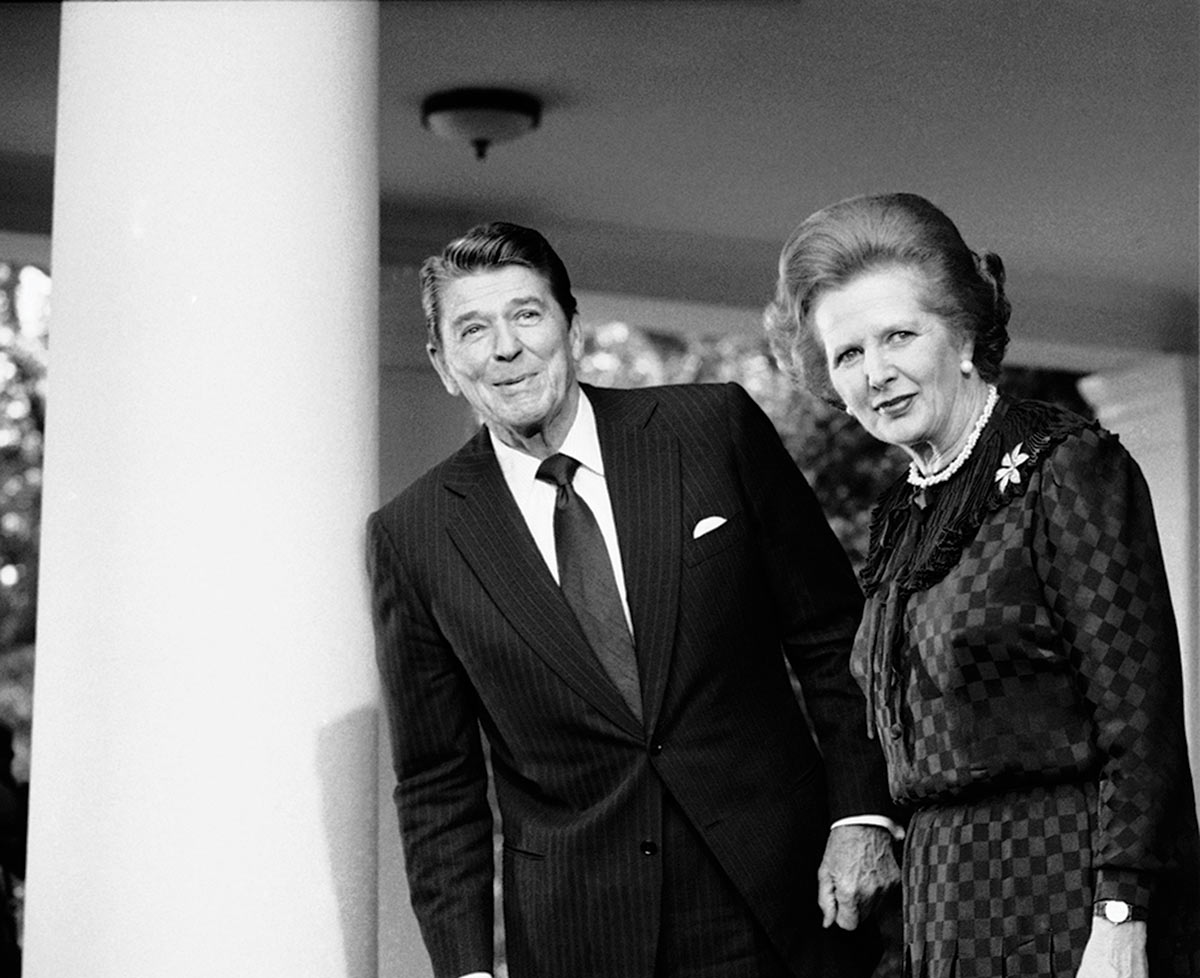

Records suggest how much America appears to have held his interest and significantly influenced the development of his thought. As a student at Eton, Britain’s most prestigious prep school, Boris Johnson reportedly tried to invite Ronald Reagan to lecture there. In interviews, Johnson has traced his childhood love of classics, still an ostentatious facet of his public persona, to his “skin crawling” realization, at age 12 or so, “that Athens was like America—open, generous, democratic—and Sparta was like the Soviet Union—nasty, closed, militaristic, totalitarian.” Later, when he served as mayor of London, he put a bust of Pericles in his office, and the hat of what he said was “some American mayor” atop it. (I asked a couple of Johnson’s teachers from Oxford, where he studied classics, if the America-Athens comparison had influenced his work there. One of them, Oswyn Murray, replied, “I came to the conclusion that he was the idlest buffoon of his generation…. His knowledge of Pericles has not improved since the age of 12 and reminds me of Hitler’s.”)

Johnson was elected president of the Oxford Union, a prestigious debate society, largely thanks to a sophisticated poll conducted by Frank Luntz, an American fellow student and a future GOP pollster. Since the early days of Johnson’s career, many of his political instincts have borne the supersize imprimatur of Americanism. His political convictions have always been secondary to the force of his personality, and since he became prime minister in July of this year, he has adopted a US president’s adversarial style when dealing with lawmakers rather than the more genteel, consensual approach traditionally associated with the UK’s parliamentary system. The allure of supreme personal power has always been strong for Johnson. As a child, he told a family friend that it was his ambition to be “world king.” Stanley Johnson recently said of his son, “He could have been president of America, but he opted to be prime minister of England.”

America looms over another aspect of Boris Johnson’s self-created mythology: his spiritual closeness to his hero Winston Churchill, whose mother was American. In his 2014 book, The Churchill Factor—a transparent exercise in parallelism—Johnson hails the wartime leader for his visionary “transatlantic plucking.” Churchill foresaw the new US-centric world order and got the United Kingdom special status within it, “with his Anglo-American self (naturally) as the incarnation of this union.”

And yet since the very beginnings of Johnson’s political career, he has also personified the bumbling British gentleman—not an archetype typically associated with the Oval Office. His exaggerated Britishness has come in handy during his push for Brexit, which has been couched, in large part, as an appeal to unthinking patriotism. (Disclosure: I worked for the campaign to keep the UK in the EU in 2016.)

There have been bumps in Johnson’s romance with the United States, of course. In a 2006 article headlined “That’s It Uncle Sam,” he threatened to renounce his US citizenship. He said it “used vaguely to tinge my sense of identity” but didn’t anymore. (Andrew Gimson, Johnson’s biographer and a former Spectator colleague, told me Johnson “used to make quite a thing of having an American passport…. I think he generally seemed to have a tremendous relish for visiting America.”)

Around that time, Johnson publicly changed his position on the United States and the Iraq War. Gone was the paean to American triumph from his visit to Baghdad, replaced by a tone that modulated between ass-covering (yes, the weapons of mass destruction were a lie, but Saddam had to go) and explicit personal regret for his support of the invasion. If this seems contradictory or at least an epic flip-flop, consider the egotism of Boris Johnson. He sees Britain as great because America is great—and vice versa.

It would be 2016 before Johnson formally severed legal allegiances to the States—not because he felt too “jolly British” to have dual citizenship but, in all likelihood, to avoid paying US taxes after a crackdown on foreign bank accounts. (What could be more American?) The same year—the year of the Brexit referendum—Johnson railed publicly against Barack Obama’s criticism of the Leave effort. Brexit was none of America’s business, Johnson said.

Besides, the United States would never accept similar interference with its own affairs.

In the Conservative Party, pro-Americanism is not unusual. America stands for democracy and capitalism; liberty and small government; consumerism and entrepreneurialism; low taxes and cheap gas; pride in the flag, the troops, and obscene wealth (all of which are considered gauche in Britain); and an anything-is-possible ethos. In his final Telegraph column before taking office as prime minister, Johnson even invoked the moon landing and “the ‘can do’ spirit of 1960s America” as inspiration for tackling the technical challenges posed by Brexit.

But his fellow feeling with the States verges on the libidinal. In a 2003 profile of Italy’s then–Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi, Johnson twice uses the word “American” as a synonym for explosive, virile energy. Johnson wrote the next year that in a Las Vegas hotel, he feels “surges of enthusiasm for America and her energy” as he looks out over the city’s “colossal neon representations of rhinestone-covered buttocks.”

Such machismo invokes a nostalgia for colonial power, which America, in Johnson’s view, inherited from Britain. The United States, he said, is “one of the finest ideological and cultural creations” of the UK. It’s as if he wants to bask in America’s glory without sharing responsibility for its failures. Now as ever, when it comes to the special relationship, Johnson wants to have his cake and eat it, too. “Whoever comes to power in Britain…will continue to try to have it both ways,” he writes in 2003’s Lend Me Your Ears. That involves “pretending a unique allegiance to both Europe and America, not because we are especially duplicitous, but because it is the sensible thing to do. We will stick with America while contriving to remain on the European ‘train.’”

The United Kingdom has gone off the European rails, steered in no small part by Johnson. The country’s relationship with America, under his leadership, will now logically assume added importance. Already, British and US officials have made enthusiastic noises about the prospect of a quick trade deal the minute the UK is out of the EU. Sitting next to Johnson on the sidelines of the United Nations General Assembly in September, Trump said, “We can quadruple our trade with the UK.” Trump has even paid Johnson the highest compliment imaginable: that he is “Britain Trump.”

“He’s happy to pose as Trump’s best buddy now,” Jonathan Freedland, a columnist for The Guardian who wrote a book about the UK and America, told me. “I think to flatter him by calling him an Atlanticist…would be a mistake, because it would imply a kind of worldview. I don’t think there is one.”

In 2004, a year and a half after his trip to Baghdad, Johnson published Seventy-Two Virgins, his first and so far (thankfully) only novel. The book is a kind of Socratic dialogue about the goodness of America in the context of the Iraq War. Its narrative features jihadists taking the US president hostage while he’s giving a speech in Parliament, then forcing the assembled dignitaries to debate whether the United States should be forced to release prisoners from Guantánamo Bay. The world, watching on TV, is invited to weigh in on the matter in a telephone referendum. The US wins by a Brexit-thin margin.

In the novel, Johnson portrays anti-Americanism, then on the rise in the UK, as a childish agenda pushed by dope-smoking hippies and effete snobs. At the same time, he channels his ambivalence through thinly veiled alter egos like Roger Barlow, a fictional Conservative lawmaker who expresses irritation as American soldiers push him around.

Barlow serves as a useful proxy for Johnson, revealing a rare deep truth about him: that for all his love of America, he desperately wants the United Kingdom to be—and be seen as—its peer. In real life, Johnson has complained about America’s lies and the UK’s supine naïveté over the Iraq invasion. In Seventy-Two Virgins, the narrator asks, “Britain wasn’t a colony of America, was she? She could hardly be called a vassal state, could she?”

Iraq was the clearest manifestation yet that this was wishful thinking, but there were, are, and certainly will be others. In 2004, Johnson wrote about an extradition case that the US-UK relationship had become “give, give, give.” In 2009 he called another US extradition request “a comment on American bullying and British spinelessness.” As the United Kingdom’s foreign minister under Theresa May, he banned the phrase “special relationship” in his office. It made Britain sound “needy,” he said. “As in so many romantic relationships, there’s an asymmetry.”

With the US-UK relationship about to enter a new phase, Johnson’s resentment of American pushiness could override his Atlanticist values. He could just as easily be backed into a corner by Britain’s economic needs and capitulate to the States completely. Politically, at least, this might be less of a problem for him than vassalage to the EU. “A peculiarity of English nativism is to see continental Europe as foreign and yet to see Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and the United States as somehow less foreign,” Freedland said. This decidedly colonial view may help Johnson rationalize difficult decisions.

Nonetheless, many Brits worry the Trump administration’s promise of a post-Brexit trade deal will make the UK adopt looser, US-style regulations and support Trump’s foreign policy priorities, notably on Iran and the Chinese multinational Huawei. In particular, many Brits fear that a trade deal would lead to further privatization of the country’s free-to-use National Health Service and the introduction to the British market of chlorinated chicken, which is common in the US but banned under European health standards. (According to a poll conducted by the consumer-advocacy organization Which? last year, nearly three-quarters of respondents oppose weakening food safety standards.)

Johnson has stressed that he will fight hard for the NHS and other interests, and Gimson, his biographer, said he sees “no evidence that Boris is a feeble negotiator.” (Johnson has apparently been practicing his golf swing, perhaps to that end.) But critics have already started labeling Johnson as Trump’s poodle.

It’s hard to predict anything about Johnson’s strategy, let alone in regard to the Brexit he is overseeing. For now, Parliament has frustrated the possibility of Britain leaving Europe without a deal (though at the time of this writing, the Johnson government was reportedly exploring workarounds). What’s more, the public could vote him out of office.

What he can be relied on is to do what he has always done: keep pandering to different audiences to advance the one true cause of Boris Johnson. Given his affinity for and appreciation of America, he—if he can get away with it—might like very much to go down as the leader who decisively steered UK foreign policy out of Europe’s thrall and back in a transatlantic direction.

Toward the end of Seventy-Two Virgins, Barlow—the character who is obviously Johnson—has the final say in the debate on America’s goodness. Held hostage by jihadists in Parliament with the US president and other dignitaries, Barlow, after some prevarication, stands up to speak. “I say vote for America!” he cries. Boris Johnson will soon find himself in a strangely similar position.