Chris Lampen-Crowell started to feel the undertow four years ago. Gazelle Sports, the running-shoe and apparel business he founded in downtown Kalamazoo, Michigan, in 1985, had grown steadily for decades, adding locations in Grand Rapids and Detroit and swelling to some 170 employees. But then, in 2014, sales took a downward turn. From the outside, at least, it was hard to see why. Gazelle Sports was as beloved as ever by local runners. People continued to flock to its free clinics and community runs. And scores of enthusiastic reviews on Google and Yelp, along with an industry ranking as one of the best running-shoe retailers in the country, gave Gazelle Sports and its e-commerce website plenty of prominence in online searches.

The problem wasn’t so much that customers had made a conscious decision to buy their running gear elsewhere, Lampen-Crowell says. Rather, a number were doing more of their overall shopping on Amazon—and as the online giant became a pervasive, almost unconscious habit in their lives, they had started dropping into their Amazon shopping carts some of the items they used to buy from Gazelle Sports. Lampen-Crowell’s initial response was to double down on marketing his company’s own website. But while that helped, there were many potential customers who still had little chance of landing on it. That was because, by 2014, nearly 40 percent of people looking to buy something online were skipping search engines like Google altogether and instead starting their product searches directly on Amazon.

By the fall of 2016, the share of online shoppers bypassing search engines and heading straight to Amazon had grown to 55 percent. With sales flagging and staff reductions under way, Lampen-Crowell made what seemed like a necessary decision: Gazelle Sports would join Amazon Marketplace, becoming a third-party seller on the digital giant’s platform. “If the customer is on Amazon, as a small business you have to say, ‘That is where I have to go,’” Lampen-Crowell explains. “Otherwise, we are going to close our doors.”

Gazelle Sports isn’t alone. Faced with Amazon’s overwhelming gravitational pull on the Internet’s shopping traffic, thousands of Amazon’s competitors—from small independent retailers to major chains and manufacturing brands—have felt compelled to join its orbit.

Setting up shop on Amazon’s platform has helped Gazelle Sports stabilize its sales. But it’s also put the company on a treacherous footing. Amazon, which did not respond to an interview request, touts its platform as a place where entrepreneurs can “pursue their dreams.” Yet studies indicate that the relationship is often predatory. Harvard Business School researchers found that when third-party sellers post new products, Amazon tracks the transactions and then starts selling many of their most popular items itself. And when it’s not using the information that it gleans from sellers to compete against them, Amazon uses it to extract an ever larger cut of their revenue.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

To succeed, sellers need to “win the buy-box”—that is, be chosen by Amazon’s algorithms as the default seller for a product. But according to ProPublica, “about three-quarters of the time, Amazon placed its own products and those of companies that pay for its [warehousing and shipping] services in that position even when there were substantially cheaper offers available from others.” As more third-party sellers have agreed to sign up for these services, Amazon has repeatedly raised its fees, with fulfillment fees rising this year by as much as 14 percent for standard-size items (and more for oversize goods), on top of similar increases in 2017.

For now, Lampen-Crowell’s primary suppliers have chosen not to sell directly to Amazon, giving Gazelle Sports and other independent retailers exclusive access to their products and, with it, a measure of insulation from Amazon’s predatory tactics. That could change, however. In 2016, Amazon backed Birkenstock into a corner, threatening to allow a deluge of counterfeit Birkenstocks onto its site—many from overseas sellers—unless the shoe company agreed to sell directly to Amazon the niche products it had previously reserved for specialty retailers. Birkenstock pushed back, but other companies, including Nike, appear to have caved to a similar demand.

Lampen-Crowell tries not to spend time worrying about whether his suppliers will one day be pressured to do the same. An entrepreneur at heart, he keeps his focus on finding ways to succeed and doesn’t let his attention stray too far into questions of Amazon’s market power. “Whether this is monopolization…” he says, and then pauses. “If you take this to the end, Amazon controls the rules.”

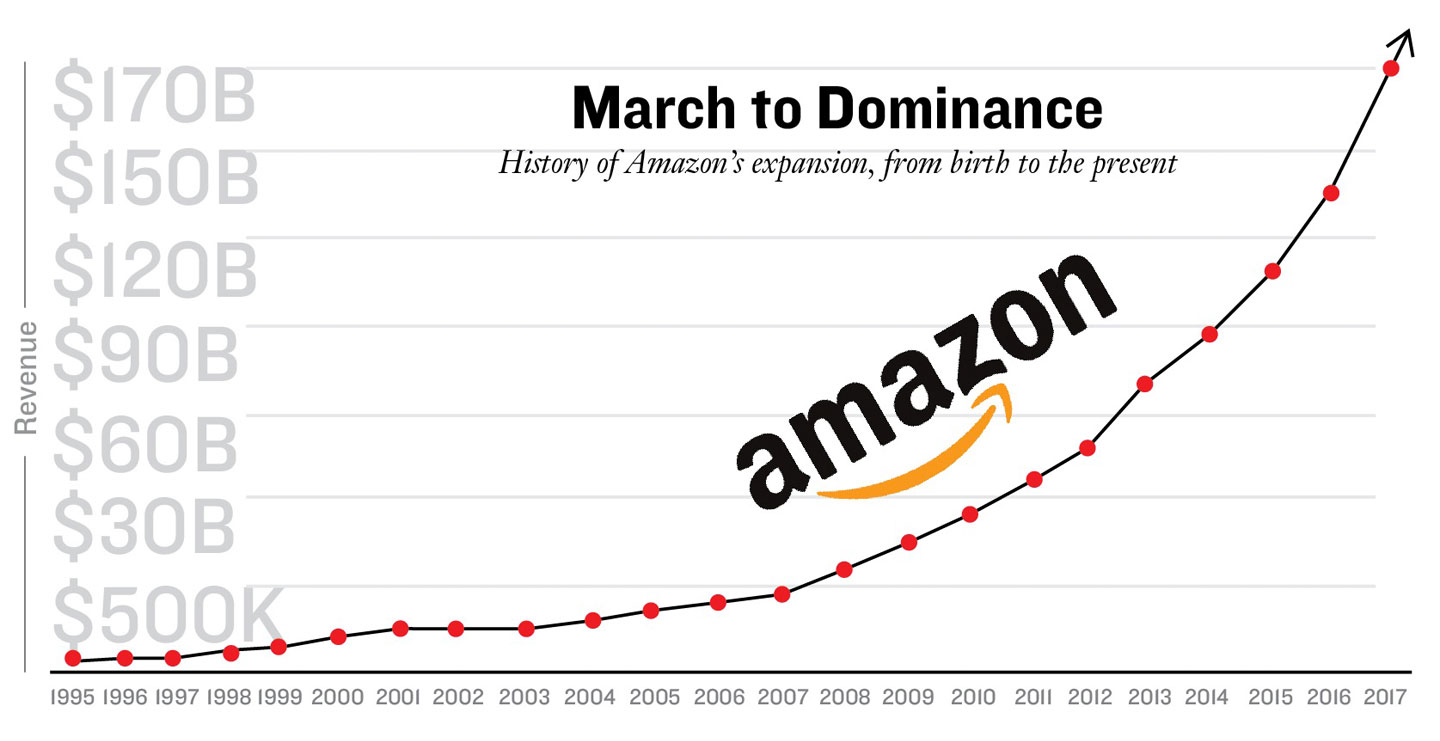

It’s easy to mistake Amazon for a retailer. After all, the company, which was founded in 1995, sells more books and toys than any other retailer, and is projected soon to become the top seller of clothing and electronics. It now captures nearly $1 of every $2 that Americans spend online.

To think of Amazon as a retailer, though, is to profoundly misjudge the scope of what its founder and chief executive, Jeff Bezos, has set out to do. It’s not simply that Amazon does so much more than sell stuff—that it also produces hit television shows and movies; publishes books; designs digital devices; underwrites loans; delivers restaurant orders; sells a growing share of the Web’s advertising; manages the data of US intelligence agencies; operates the world’s largest streaming video-game platform; manufactures a growing array of products, from blouses to batteries; and is even venturing into health care.

Instead, it’s that Bezos has designed his company for a far more radical goal than merely dominating markets; he’s built Amazon to replace them. His vision is for Amazon to become the underlying infrastructure that commerce runs on. Already, Amazon’s website is the dominant platform for online retail sales, attracting half of all online US shopping traffic and hosting thousands of third-party sellers. Its Amazon Web Services division provides 34 percent of the world’s cloud-computing capacity, handling the data of a long list of entities, from Netflix to Nordstrom, Comcast to Condé Nast to the CIA. Now, in a challenge to UPS and FedEx, Amazon is building out a vast shipping and delivery operation with the aim of handling both its own packages and those of other companies.

By controlling these essential pieces of infrastructure, Amazon can privilege its own products and services as they move through these pipelines, siphoning off the most lucrative currents of consumer demand for itself. And it can set the terms by which other companies have access to these pipelines, while also levying, through the fees it charges, a tax on their trade. In other words, it’s moving us away from a democratic political economy, in which commerce takes place in open markets governed by public rules, and toward a future in which the exchange of goods occurs in a private arena governed by Amazon. It’s a setup that inevitably transfers wealth to the few—and with it, the power over such crucial questions as which books and ideas get published and promoted, who may ply a trade and on what terms, and whether given communities will succeed or fail.

Amazon is “something radically new in the history of American business,” New Yorker writer George Packer has observed. But it’s not without antecedents. In the 19th century, men like Cornelius Vanderbilt and John D. Rockefeller harnessed a disruptive new technology—the railroad—and used the control that it gave them over market access to weaken their industrial competitors and extort money from farmers and small businesses. Their actions sparked a broad movement against monopolies, which led, over the following decades, to the passage of a robust body of antitrust laws. The central purpose of these laws was to protect liberty and democracy from concentrated economic power, or what Franklin Roosevelt called “industrial dictatorship.”

By the time Bezos set up his bookselling operation on the Internet, however, these laws were no longer being enforced in accordance with their original purpose. In the 1970s, an ideological revolution swept through the fields of law and economics. Led by the conservative legal scholar and former Nixon solicitor general Robert Bork, among others, this new school of thought dismissed concerns about the impact of monopolies on the rights of citizens and even on competition. Its proponents argued that antitrust law should be reduced to a single, narrow goal: maximizing efficiency. And efficiency, they insisted, was something that big, consolidated corporations could deliver better. These ideas were codified under Ronald Reagan, whose administration left the antitrust laws intact but altered the way that regulators interpreted and enforced them. These changes won support from an ascendant faction of liberals, who made efficiency more appealing by recasting it as the source of lower prices for consumers.

“Antitrust laws have been largely reduced to a technical tool to keep prices low,” notes Lina Khan, director of legal policy at the Open Markets Institute. As a consequence, so long as Amazon has appeared to benefit consumers, it’s been allowed to grow using tactics that would once have drawn antitrust scrutiny. Amazon has an extensive history, for example, of selling goods at a loss in order to wrest market share from competitors that lack the financial backing to sustain similar losses. Bezos, a former hedge-fund executive who has an unparalleled gift for selling his vision to Wall Street, has always been candid with investors about this strategy. In a letter to shareholders after the company went public in 1997, he wrote that he would prioritize “long-term market leadership considerations rather than short-term profitability.” Over the next six years, investors barely winced as Amazon lost $3 billion selling books and other items below cost. The investment paid off: Bookstores shut down in droves, and today nearly half of all books, both print and digital, are sold by Amazon.

Amazon has also used below-cost selling to crush and absorb upstart competitors. In 2009, it acquired the popular shoe retailer Zappos after reportedly losing $150 million selling shoes below cost in order to force the rival company to the altar. Likewise, when Quidsi, the firm behind Diapers.com, emerged as a vigorous competitor, Amazon offered to buy it; when Quidsi’s founders refused, Amazon slashed its diaper prices below cost. Bleeding red ink, Quidsi eventually agreed to Amazon’s offer. Over time, this behavior has had a restraining effect: Start-ups intent on challenging Amazon are unlikely to find investors and so never get off the ground. “When you are small, someone else that is bigger can always come along and take away what you have,” Bezos has said.

Amazon’s many tentacles provide it with novel ways to strong-arm suppliers. By leveraging the interplay between the different parts of its business—retail, e-commerce, manufacturing—it can amplify its market power over them. For instance, when Amazon began producing its own apparel two years ago, one aim was to erase the only real bargaining chip that fashion brands have: their ability to decline to sell to Amazon. Speaking at a fashion-industry event, Jeff Yurcisin, a vice president of Amazon Fashion, explained that uncooperative designers would now face knockoffs: “When we see gaps, when certain brands have actually decided for their own reasons not to sell with us, our customer still wants a product like that.”

Amazon’s dominance has been aided by Bezos’s prescient grasp of how the seemingly wide-open Web could be turned into a winner-take-all environment. In 2005, Amazon launched Prime, a membership program that provides free two-day shipping and other perks for $99 a year. As a stand-alone service, Prime is a money-loser; Forrester Research estimates that Amazon loses $1 billion a year on the shipping alone. The point of getting people to fork over $99 has never been about the money, though—it’s about the psychology. When people pay for Prime, they naturally want to maximize the value in free shipping they derive from it by doing more of their shopping on Amazon. Already, some 80 million Americans, accounting for more than half of the country’s households, are Prime members. Studies show they are less likely to comparison-shop, and they spend almost twice as much with Amazon as non-Prime customers.

With Alexa, Bezos has found a way to lure people even deeper into Amazon’s ecosystem. Alexa is the voice assistant that powers the company’s Echo speaker, and it makes buying from Amazon as effortless as a passing thought. “The fact that it’s always on, you never have to charge it, and it’s there ready in your kitchen or your bedroom or wherever you put it, the fact that you can talk to it in a natural way—removes a lot of barriers, a lot of friction,” Bezos has said of the speaker. One such friction is choice: If you ask Alexa for batteries, you won’t get to choose Duracell or Energizer; Amazon’s brand is the only option. With Alexa, Amazon will “slowly but surely take control of your preferences,” predicts Scott Galloway, a professor of marketing at New York University. The digital giant has already sold at least 20 million of these devices.

Although Amazon continues to earn relatively meager profits compared with rivals like Walmart and Apple, its stock price has soared, almost doubling in value over the past 18 months and making Bezos the wealthiest person in the world. Investors see where this is heading. In 2016, Chamath Palihapitiya, a venture capitalist and owner of the Golden State Warriors, put a name to it: Amazon, he told an audience of fellow investors, “is a multitrillion-dollar monopoly hiding in plain sight.”

What Amazon’s giddy investors already understand, however, regulators have so far failed to grasp. Last June, Amazon announced its intention to buy Whole Foods. The deal gives Amazon a prominent foothold in the pivotal grocery industry and much else besides. With Whole Foods, Amazon gains new ways to cement its dominance online, including by extending its package-delivery infrastructure to 470 stores nestled among millions of urban consumers. And it allows the company to blur the distinction between online and offline retail, accelerating the spread of digitally driven commerce and, with it, Amazon’s power. Yet, just two months after the deal was announced, the Federal Trade Commission gave it the green light, concluding that the merger did not warrant an in-depth review.

As it grows, Amazon is exposing the deficiencies of the Reagan-era changes in how we think about corporate concentration. By collapsing antitrust enforcement to consider only prices, we have lost sight of what earlier generations knew about monopolies: that they can harm us as producers of value, not merely as consumers of it. And their control over our livelihoods and the fate of our communities is inherently political: It’s a threat to liberty and democracy.

Economists have recently begun to document a link between corporate concentration and rising inequality. Dominant companies, they’re finding, are funneling the spoils to a small number of people at the top. And by reducing the number of their competitors, these companies are also making it harder for workers to get a fair wage and for producers to get a fair price. A particularly troubling data point in this research is the loss of a long-standing pathway to a middle-class life: starting a business. The number of new firms launched each year has fallen by nearly two-thirds since 1980, and many economists believe that corporate power is to blame. This lack of start-ups is fueling a broader decline in the ranks of small business: Between 2005 and 2015, the number of small retailers fell by 85,000, a drop of 21 percent relative to population.

In this story of concentrated power and wealth, Amazon is a central character. In a 2016 survey, independent retailers ranked competition from Internet retailers like Amazon as the biggest threat to their businesses, more worrisome than big-box stores or rising health-insurance costs. And their decline is having ripple effects up the supply chain. As more of the market shifts to a single gatekeeper, manufacturers say they are having a harder time introducing new products. Local businesses “are in a much better position as small retailers to do that boot-strapping,” says Michael Levins, the founder of Innovative Kids, a book and puzzle producer that’s been in business for 29 years.

At the same time that many communities are seeing local businesses disappear, they’re also losing retail jobs. This past year, more people lost jobs in general-merchandise stores than the total number of workers in the coal industry. Even as Amazon expands its network of warehouses, it isn’t creating enough jobs to make up for the losses it’s causing. The basic math of what’s under way is startling: Retail accounts for about one in 10 American jobs, and Amazon needs only half as many workers to distribute the same volume of goods as traditional stores require. Plus it’s likely to need even fewer workers in the future: Since 2015, Amazon has invited elite engineering teams to compete in an annual robotics challenge. Their mission is to design a robot that can select and grasp assorted items, a task that, for now, only humans can do.

This kind of wholesale upending of an industry happens periodically, and, as a rule, we don’t run out of jobs. But today, in the absence of a flush of new businesses creating new opportunities, work for many people has become increasingly precarious—and, in the case of Amazon workers, punishing. People who work inside the company’s warehouses describe the pace as grueling, with “unit-per-hour” rates set so high that failure and exhaustion are routine. Amazon’s approach to work is at once futuristic and a throwback to labor’s distant past. Robots zip around, laden with products, while many of the people they interface with are temporary employees. Amazon calls these workers “seasonal,” but, in fact, it relies on them year-round.

As it moves into package delivery, Amazon is bringing its labor model along, relying in part on Amazon Flex drivers, who use their own vehicles, take directions from an app, and are paid a piece rate for each batch of boxes they deliver. The impacts are already being felt at the US Postal Service and UPS, whose hundreds of thousands of unionized employees constitute one of the last surviving corners of the working middle class. A few months ago, over the objections of the Teamsters union, UPS began placing ads for drivers who will use their own vehicles.

As a result of the economic shifts that Amazon is helping to propel, the country is being divided into a starkly unequal geography. Only a handful of metro areas are gaining significant numbers of good jobs from Big Tech. And as the formation of new businesses declines, they’re also being consolidated into fewer places: In contrast with previous recoveries, when new firms were widely dispersed, half of all businesses started between 2010 and 2014 were located in just five metro areas. Even winning cities are marked by disparity: In Seattle, where Amazon is headquartered, the median home value now exceeds $700,000, while the unsheltered homeless population doubled over 10 years. It’s not hard to imagine a future in which Amazon’s cashier-less supermarkets and nondescript bookstores populate better-off neighborhoods, while other communities become increasingly barren of commercial activity.

In the left-behind towns and neighborhoods, the despair that has set in stems from more than just economic hardship. There is a pervasive sense of powerlessness that is toxic to democracy. In 1946, the sociologist C. Wright Mills and the economist Melville J. Ulmer published a detailed study of several matched pairs of cities. The cities in each pair were similar in all respects except for one main difference: One city’s economy was composed of many locally owned firms, while the other’s was largely controlled by absentee corporations. The cities that possessed a degree of local economic power had a bigger middle class and a greater variety of jobs, Mills and Ulmer found. But their most important findings had to do with civic health. The cities with a robust local economy invested more in public infrastructure and services, and their residents were involved in community affairs in greater numbers.

Today, using large-scale statistical techniques, sociologists have confirmed Mills and Ulmer’s broad conclusions, finding, for example, that communities that possess more local economic power are better able to solve problems. But these ideas are no longer reflected in policy. Now, instead of actively seeking to disperse economic power, policy-makers encourage its concentration. Many elected officials are as enthralled with Bezos as his investors are, and they’ve been equally willing to fund Amazon’s growth. Congress has repeatedly declined to pass legislation that would allow states to require out-of-state retailers to collect sales taxes. This allowed Amazon to largely avoid collecting sales taxes for nearly two decades, giving it a price advantage that research shows helped drive shoppers to its site. Then, as Amazon’s warehouse expansion began to compel its compliance with sales taxes, the company started angling for local development incentives. It’s raked in more than $1.1 billion through these deals, according to Good Jobs First, and more than half of the warehouses that Amazon built between 2005 and 2015 received public subsidies.

Then, last fall, Amazon set off a frenzied bidding war to land its second headquarters. In the ensuing months, as the leaders of more than 200 cities groveled to attract the company’s eye, they sent a clear message to their constituents: Amazon’s widening reach is something to be wished for fervently. For Amazon, this public-relations windfall—coming at the very moment when some are beginning to question its power, and propelled, in many cases, by leading progressive mayors—may prove even more valuable than the subsidies that elected officials are offering. And those offers have been astonishingly large: Maryland is dangling $5 billion, along with close proximity to Congress. In New Jersey, meanwhile, Senator Cory Booker, former governor Chris Christie, and Newark Mayor Ras Baraka put together an offer worth $7 billion. That’s $2 billion more than Amazon says its new headquarters will cost.

In June of 2016, Senator Elizabeth Warren gave a headline-grabbing speech calling for action to check monopoly power. She singled out several dominant companies, including Amazon, noting that “the platform can become a tool to snuff out competition.” And she argued that we should use antitrust policy to break up concentrations of power and broaden opportunity, presenting a progressive economic vision that has more to offer people than simply an enhanced social safety net.

In recent months, a growing number of political leaders have started to make the case for restoring antitrust policy to its former strength and purpose. The US House of Representatives now hosts the newly formed Antitrust Caucus. Its founders include Congressman Ro Khanna (D-CA), who, interestingly, hails from Silicon Valley, and who urged antitrust enforcers last summer to undertake a much more thorough review of the Amazon–Whole Foods merger than they did. Another member is Congressman David Cicilline (D-RI), who’s been outspoken about the destructive power of dominant tech platforms to manipulate consumers and impede start-ups. The caucus’s first piece of legislation, which would require the antitrust agencies to retrospectively review the effects of mergers they have approved, has been introduced by Congressman Keith Ellison (D-MN), who believes that “massive monopolies are threatening our democracy.”

Democrats aren’t the only ones pushing for a more muscular approach to monopolies. Missouri Attorney General Josh Hawley, a Republican and candidate for the US Senate, has launched an antitrust investigation of Google.

How might we use the tools of antitrust law to check Amazon’s power? One approach would break the company into two pieces by spinning off its e-commerce platform from its retail operation, thereby eliminating the conflict inherent in controlling market access for one’s competitors. We could then designate the resulting platform company as a common carrier, obligating it to offer all sellers access on equal terms, just as we did with the railroads. Alongside this, we need to once again police predatory pricing, the practice of selling goods below cost to drive out competition. Antitrust enforcers and the courts dismissed predatory pricing as a concern in the 1980s on the grounds that the tactic rarely succeeds. Amazon has shown otherwise.

Amazon will undoubtedly respond to any effort to rein it in by making its dominance seem like the inevitable outcome of technological progress. When Bezos was asked several years ago about his company’s effect on publishers and booksellers, he responded: “Amazon is not happening to bookselling; the future is happening to bookselling.” Bezos would like us to believe that we shouldn’t expect to enjoy the benefits of the digital revolution without surrendering our markets to Amazon’s control. But history tells a different story: Federal antitrust cases against AT&T, IBM, and Microsoft all produced a surge of innovation and start-up activity in their wake.

Back in Michigan, Lampen-Crowell is eager to compete. He’s added a series of injury-prevention workshops to the calendar, along with a schedule of weekly runs with various goals, from improving speed to helping residents stay active during the state’s long winters. The question now is whether we as citizens will insist that this business, and many others like it, have a fair chance to succeed.