A Shower of Sparks

The year Europe revolted.

The Year Europe Revolted

A new history by Christopher Clark on the 1848 revolutions.

In the final pages of Revolutionary Spring, the historian Christopher Clark writes that “the revolutions of 1848 seemed as old as ancient Egypt when I learned about them at school.” Now, however, he sees important parallels with the present. Just as revolutionary flames seemed to leap from country to country in 1848, so they have done in recent decades, notably in the Arab Spring of the early 2010s, which spread from

Books in review

Revolutionary Spring: Europe Aflame and the Fight for a New World, 1848–1849

Buy this bookTunisia to Libya, Egypt, Syria, and beyond. Just as politics today often involves “a blend of carnivalesque style and insurrectionary logic,” so it did 175 years ago (the January 6 attack on the Capitol, Clark writes, “was thick with echoes” of 1848). Then, as now, ideologies were in flux: Self-identified “liberals” and “radicals” oscillated between uneasy alliance and open conflict, while populist nationalism proved to be the enemy of progressive social change. “As I wrote this book,” Clark concludes, “I was struck by the feeling that the people of 1848 could see themselves in us.”

But is Clark right to emphasize these connections? One certainly cannot criticize his command of the material: Revolutionary Spring’s 74 pages of tightly packed small-font endnotes—nearly 2,000 of them, in at least 10 languages—testify to the vast extent of his research. Although the events he surveys, each with its own chronology and cast of characters, took place across a score of separate locales, he manages to distill everything into a clear and compelling narrative, aided by his knack for the striking phrase. And Clark also has an eye for wonderful details, as in his description of observers climbing the highest buildings in Milan to observe the enemy outside the city’s walls. “To save time,” he tells his readers, “they attached their reports to a metal ring and sent them whizzing down ziplines to the ground, where they were picked up and taken to headquarters by the boys of a college of orphans.”

Yet despite having written a book that emphatically deserves the term “magisterial,” Clark ends up straining in his attempts to connect 1848 to the present moment. Sometimes, the differences between earlier times and our own are more instructive than the similarities. And the similarities that Clark points to are overshadowed by one very great difference: the almost unlimited faith that the people of 1848 put in the idea of revolution itself. That faith died in the ashes of the 20th century.

The very first revolution of 1848 testified to that faith. In Palermo, Sicily, printed notices appeared at the start of the year announcing that an uprising—and an era of “universal regeneration”—would begin on January 12. As Clark notes, it might have seemed a silly idea for the conspirators to announce their plans ahead of time—but there was no conspiracy. The author of the notices, a veteran of radical politics named Francesco Bagnasco, thought “the announcement of a revolt would suffice to bring one about,” and he was right. Long-standing resentment of the king of Naples’s heavy-handed rule, exacerbated by severe economic inequality, led crowds to pour into the streets on the appointed day to fulfill—if only for a short time—the dream of Sicilian independence.

Revolution soon spread to mainland Europe, driven by social conflict. Europeans were not, in the aggregate, poorer than they had been in the past, but the economic disruptions of the industrial revolution had created a newly mobile labor force living a starkly precarious existence, especially in the cities. Nor were reform-minded Europeans as ready as they once had been to accept social misery as inevitable. As emerging socialist movements insisted, impoverishment was a human phenomenon, and human action—political action—could relieve it. In region after region, precarity and the hope for a more secure life fueled popular support for political movements struggling against corrupt, despotic, and foreign rulers (the working classes generally did not start the revolutions, but revolutions could not succeed without them). And in region after region, the news of uprisings elsewhere fell on the dry timber of troubled societies like a shower of sparks.

In February, the French overthrew King Louis-Philippe and proclaimed the Second Republic (Napoleon Bonaparte had overthrown the first one 49 years earlier). The next month, revolution spread to the German states, with many rulers, notably in Austria and Prussia, compelled to promise liberal reforms. They granted constitutions and guaranteed rights. Delegates from the German territories assembled in Frankfurt to start planning for German unification. And from there, uprisings spread across Central Europe and Italy. National minorities throughout the Austrian, Ottoman, and Russian empires called for autonomy or independence. The 1848 revolutions extended as far east as the Balkans and the Ionian Islands and led rulers in many places to make anxious, preemptive concessions to the reformers.

The 1848 revolutions also had consequences beyond Europe, notably in France’s overseas colonies, where enslaved people seized freedom for themselves in anticipation of legal emancipation—which the Second Republic duly enacted. Clark gives far more attention to 1848’s global ramifications than earlier historians, and also to the role of women—although feminists who hoped the revolutions would bring women expanded rights were everywhere met with bitter disappointment. France’s Jeanne Deroin, who called for female suffrage, tried to run for a seat in Parliament herself, and campaigned for the creation of workers’ cooperatives, ended up in prison during a wave of postrevolutionary repression.

Surprisingly, Clark writes, self-conscious revolutionaries like Deroin “tended to play a very marginal role in the events of 1848.” Instead, most often, uncoordinated spontaneous uprisings led to a sudden and unexpected collapse of authority, followed by frantic efforts to cobble together a new political order. The pattern repeated itself in place after place, with a virtually identical vocabulary. “The same words rang out everywhere: constitution, liberty, freedom of the press, association and assembly, civil (or national) guard, franchise reform.” Clark also points to a similar “euphoria” that gripped revolutionary crowds throughout Europe, especially in the cities. He writes of “the sense of immersion in a collective self, the presence of an emotion so intense that it is almost painful.”

In writing these words, Clark clearly has more recent scenes in mind as well: Tiananmen Square in Beijing in 1989; Tahrir Square in Cairo in 2011; the Maidan in Kyiv in 2014—history not exactly repeating itself but rhyming, as Mark Twain once put it. The parallels are clear. But they are also, in an important sense, deceptive.

For what did the euphoric crowds of 1848 think they could accomplish, beyond the immediate goals of obtaining a constitution and national rights? In this very long and detailed book, this is one of the few questions to which Clark does not devote sufficient attention. In his conclusion, he refers to “a mythical ideal of revolution as the generative moment when actors in pursuit of a new order of things smash the world and make it anew in the image of their vision.” But to the men and women of 1848, the idea that a revolution could create a whole new social order, perhaps even change human nature itself, was not simply a myth: It was a burning faith they had inherited from their own recent past, and it is to that past, not our own present, that 1848 is most closely linked.

As Clark himself notes, very late in the book, “The revolutions of 1848 broke out in a world that remembered an earlier epoch of transformation.” He then briefly cites some of the “rhymes and echoes” of that earlier epoch: Phrygian liberty caps, the slogan “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity,” and the name “Committee of Public Safety,” all from the French Revolution of 1789. He might have added the concept of the republic itself. France not only proclaimed itself a republic soon after 1789 but subsequently sponsored (often at bayonet point) the founding of more than two dozen other republics throughout Europe. But at the start of the year 1848, every significant state in Europe, with the sole exception of Switzerland, again had a hereditary ruler. In other words, the 1848ers were following a sort of script.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →And the script was not limited to words and slogans. The 1848ers still remembered—and many still believed in—the wild hopes of that earlier epoch for the radical transformation of humankind: the imminent end to all forms of oppression and the arrival of an era of equality and justice. The French revolutionaries had not only held those hopes but also did more than any other group to invent the modern idea of “revolution” as a means for realizing them. Before the era of the French Revolution, the word had denoted a sudden, unpredictable, and most likely violent change of regime, but little more. Many political philosophers and political actors, as the historian Dan Edelstein noted in a recent article for the Journal of the History of Ideas, tended to see “revolutions” as something to avoid. They designed political systems with the goal of preventing revolutions. But in the late 18th century, for millions of Europeans, “revolution” ceased to be a problem and became a solution. It ceased to be a sudden and unpredictable event and became a conscious program driven by human will that could continue indefinitely into the future. It became a means of repairing injustice, of relieving misery, of building new nations, and of regenerating the spirit. It was liberation, not merely from oppression but from unhappiness. “Happiness is a new idea in Europe,” Saint-Just declared in 1794.

After the Revolution of 1789 had given way to the Terror of 1793–94 and then Napoleon Bonaparte’s dictatorship and empire, many Europeans muted those exalted hopes. Many subsequent revolutionary movements, including those in Spain and Italy in 1820 and France in 1830, had more modest goals than their great predecessor. Like the protesters in 21st-century Cairo and Kyiv, they fought principally for a liberal constitution, the rule of law, and a guarantee of human rights. But the old dreams of changing human nature and bringing about an era of equality and peace remained potent. In Palermo, Francesco Bagnasco spoke of “universal regeneration,” of relieving popular misery, and he promised the blessings of heaven itself on the Sicilian Revolution. The men who took power in France the next month named a common worker as a member of the provisional government and promised sweeping social reforms, beginning with a series of national workshops for the unemployed. Throughout Central and Eastern Europe, the nationalists among the revolutionaries of 1848 spoke of reviving ancient nations, freeing them from imperial oppression, cleansing them of troublesome minorities, and forging them anew.

If the 1848 revolutionaries achieved less than their 18th-century predecessors had, it was not because of any lack of ambition, but because of the strength of the opposition. Europe’s ruling elites in 1848, unlike those in 1789, knew exactly what revolution meant, and they saw the threat to their power with limpid clarity from the start. More than a few regimes (notably in Britain, Scandinavia, and Spain) in fact managed to avoid revolution thanks to an adroit combination of strategic concessions and targeted repression.

In France, Louis-Philippe lost his throne, but the social elites soon regrouped and dominated the election of the new republic’s Parliament: Two-thirds of its members had held office under or had otherwise sworn an oath of loyalty to the monarchy. The elites also recognized, as Parisian radicals did not, that France was still a heavily rural society and that the peasantry had little sympathy for social programs aimed largely at urban workers. Parisian radicals in turn denounced the elections for what the novelist George Sand called the “perversion” of the public will and a “false national representation.” There followed, with sad inevitability, the bloody confrontation of the June Days of 1848, in which the French Army put down a Parisian insurrection with thousands of casualties and decisively ended the revolution’s radical phase.

The same pattern emerged elsewhere. Clark notes the shrewd maneuvering of Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm IV, who strategically withdrew his army from Berlin only to reimpose his authority later. Faced with Hungarian calls for complete autonomy, the Austrian emperor exploited the resentment of other national minorities who would then have to live under Hungarian rule. As his troops fought the Hungarian revolutionaries, Croats joined the emperor’s cause.

Ruling elites also cooperated across borders, notably in the suppression of the last great revolution of the period, in Rome, by a France now presided over by Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte, soon to be Emperor Napoleon III. Clark insists that we should not think of the 1848 revolutions in terms of success or failure, and he notes their many long-term effects, including the spread of constitutionalism and the consolidation of recognizably socialist programs on the left. Still, almost everywhere in Europe, the actual forces of revolution were defeated.

It is no accident that the most vivid character in Revolutionary Spring is also 1848’s greatest martyr: Robert Blum, the German “former bronzeworker, lantern-seller, theater-administrator and autodidact publisher of radical essays and lexicons,” who opposed the ethnocentric nationalism of many of his comrades. In October 1848, Blum traveled to revolutionary Vienna to help defend it against the approaching armies of the emperor. Arrested when the city fell, he died in front of a firing squad. His touching letter of farewell to his wife—“Everything I feel runs away in tears”—became a holy relic for generations of German revolutionaries.

In the conclusion to Revolutionary Spring, Clark poses a series of what-if questions about 1848. What if the liberals had not, in many cases, abandoned their radical allies? What if the radicals had muted their demands? It is tempting to play that game: Liberals and radicals love to blame each other for their collective defeats. But Clark’s own stirring narrative strongly suggests that, in 1848, the choices made by these groups mattered far less than the sheer strength of reaction and what the great historian Arno Mayer called the “persistence of the Old Regime.”

This is not the world we live in today. The men and women of 1848 had a faith in what revolutions could achieve that is far harder to sustain after seeing what that faith led to in the Soviet Union, China, and Cambodia. Likewise, many of these revolutionaries—though not all, by any means—justified violence in a way that very few radicals and liberals would be willing to do today. Yet the alternatives do not seem to offer much hope. In the West, many still echo George Sand’s frustration with the electoral system and the way it produces results so often at odds with the interests of the people. But nonviolent protest methods, from Occupy Wall Street to the French gilets jaunes and Nuit Debout, have also failed to achieve any of their desired results. Clark himself speaks of “the often shallow and incoherent politics of today’s pop-up protests,” which he compares unfavorably to the rigorous 19th-century reformism of France’s Louis Blanc.

The opposition is different as well. The Old Regime persists no more. The dominant neoliberal elites of the West enthusiastically voice their support for the rule of law, regular democratic elections, and human rights. Passionately cosmopolitan, they excoriate nationalism even as their policies help push millions into the arms of the nationalist populist right in country after country. Faced with this situation, the left is forced either to join broad liberal coalitions (à la Joe Biden’s) that are unlikely to achieve serious structural reforms of the economy or of government (such as a reining-in of the Supreme Court), or to hope that a more successful version of Bernie Sanders, Jeremy Corbyn, or Jean-Luc Mélenchon will someday lead a radical movement to victory. But revolution, in any case, is off the table. And while the instructive and engaging Revolutionary Spring is a joy to read, one should not read it in the hopes of finding, in 1848, lessons for 2023.

More from The Nation

What Luigi Mangione and Daniel Penny Are Telling Us About America What Luigi Mangione and Daniel Penny Are Telling Us About America

When social structures corrode, as they are doing now, they trigger desperate deeds like Mangione’s, and rightist vigilantes like Penny.

Donald Trump Is the Authentic American Berserk Donald Trump Is the Authentic American Berserk

Far from being an alien interloper, the incoming president draws from homegrown authoritarianism.

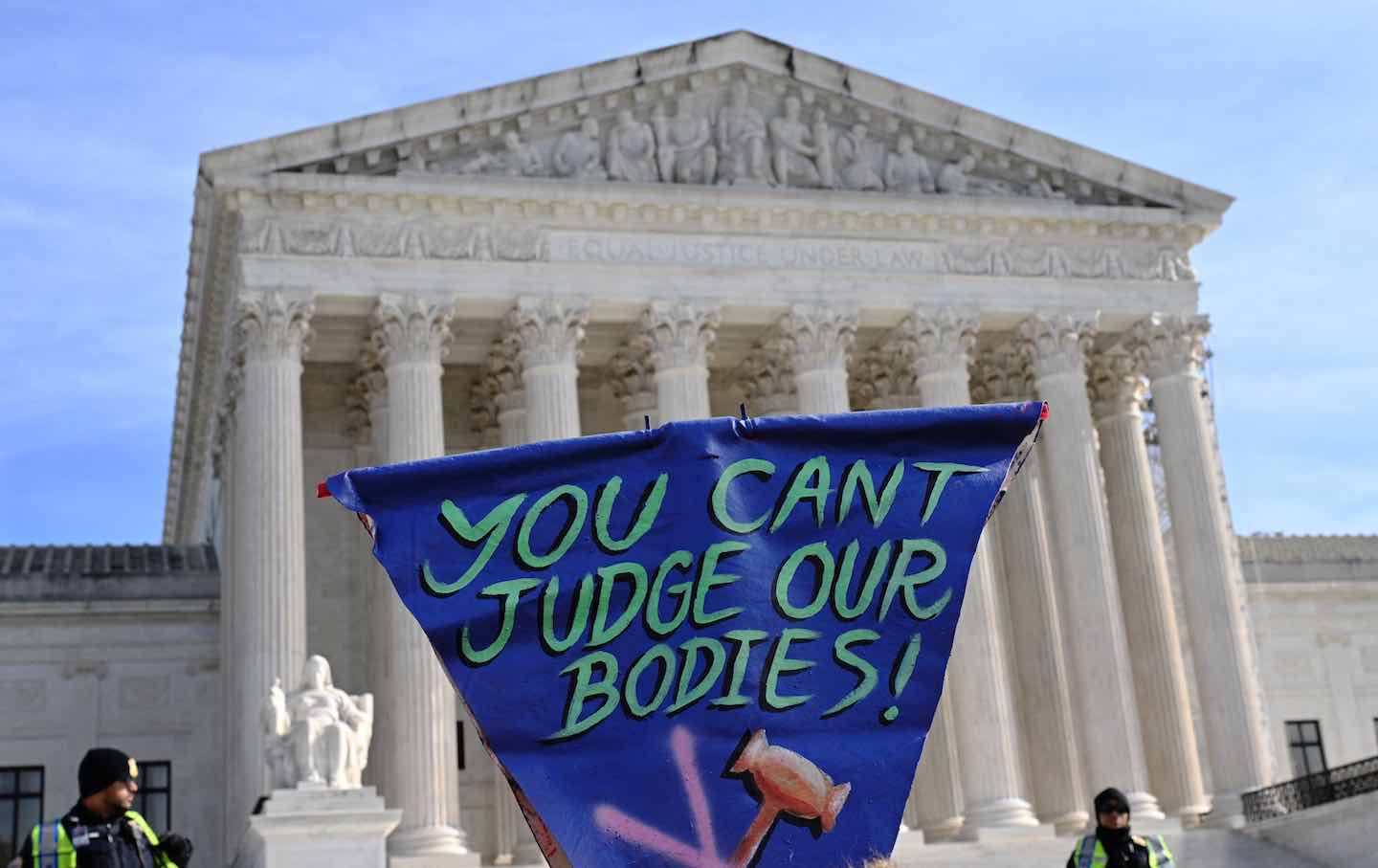

Banning Trans Health Care Puts Young People at Risk of Harm Banning Trans Health Care Puts Young People at Risk of Harm

Contrary to what conservative lawmakers argue, the Supreme Court will increase risks by upholding state bans on gender-affirming care.

If Democrats Want to Reconnect With the Working Class, They Need to Start Listening to Unions If Democrats Want to Reconnect With the Working Class, They Need to Start Listening to Unions

The Democrats blew it with non-union workers in the 2024 election. Unions have a plan to get the party on message.