I Founded Student Activists Against Sexual Assault. A New Lawsuit Could Make My Work Impossible.

A defamation suit against leaders of an anti–sexual assault campus group could allow assailants to weaponize the court system against advocates.

Students and alumni call for a third-party audit of the mishandling of sexual assault cases on Liberty University’s campus at a rally in Lynchburg, Va. on Nov. 4, 2021.

(Kendall Warner / AP)In October 2020, a University of Maryland student referred to as “Jane Roe” filed a Title IX complaint alleging that she had been sexually assaulted by two of her male classmates. In September 2021, UMD found the boys not responsible.

It’s what happened next that is unusual: One of the accused students, referred to as “John Doe,” filed a federal lawsuit alleging that two UMD graduates, who at the time occupied leadership positions in the campus student group Preventing Sexual Assault, had defamed him. Doe alleges the students “undertook a campaign” to ruin his life by calling him a rapist and stating that he was still “under investigation” after Jane Roe’s Title IX case had been dismissed.

The defamation suit is pending, and details relating to it are murky, as most of the relevant documents remain under seal. We have no way of knowing whether the student advocates actually made these statements—and, if they did, whether they accurately reflected Doe’s actions or evidence drawn from additional investigations against him. Indeed, we don’t know if any more investigations are ongoing.

What we do know, of course, is the chilling effect that the defamation claim Johnny Depp won against his former wife Amber Heard has had on sexual assault claims. Depp argued that Heard had defamed him on charges that had already been proven in a British court. Safe Horizon’s vice president of domestic violence shelters, Kelly Coyne, told MSNBC in reaction to the Depp v. Heard verdict, “We often see clients that face backlash when they come forward.… They have to choose which abuse is worse: what is happening in their relationship or what they will receive when they come forward.” Other advocates agree.

And the UMD suit is an early indication of how accused assailants could further weaponize the court system—this time against advocates.

Defamation suits targeting the accusers in cases of sexual assault are a potent weapon in the broader war against sexual assault survivors and those who seek to support them. As defamation suits from alleged perpetrators against their alleged victims multiply, victim support organizations are being forced to rethink their strategies to protect both themselves and survivors. TIME’S UP Legal Defense Fund reported to The Intercept that since 2018 it has awarded 62 grants to deal specifically with victims who fall prey to defamation suits. According to a survey by Know Your IX, a survivor justice legal advocacy group that supports students, 23 percent of student survivors said either the person they accused of assault or that person’s attorney threatened to sue them for defamation, 19 percent said they were warned by their school of the possibility of a defamation suit, and 10 percent have faced “retaliatory complaints” filed by their assailants. Earlier this year, Jezebel reported on an increasing number of successful “anti–male bias” lawsuits in response to disciplinary action related to campus sexual assaults.

Meanwhile, in June, the Connecticut Supreme Court ruled 7-0 that a former student at Yale could be sued for defamation based on the allegations of sexual assault that she made to campus administrators. The court ruled that, unlike the immunity that survivors are granted for allegations made in a criminal prosecution, a survivor’s Title IX accusations are not protected because the accused has fewer rights. This ruling, like the Depp verdict, will reinforce the message that survivors hear from the culture at large: that it’s often not worth facing the emotional distress and sexualized character assaults that await most victims of assault who come forward to name their assailants.

Combined with the impact of the Connecticut case, the pending Maryland suit may represent a new, fiercely repressive age in the struggle to report and process legitimate claims of sexual assault. Soon it may not only be the victims themselves who are legally and financially vulnerable; depending on the outcome of the Maryland suit, advocates seeking to lend support to survivors could face lawsuits too.

When educational institutions and criminal courts fail to provide meaningful protection, where can students turn? Student-run advocacy organizations are the only university-affiliated groups that prioritize the protection of survivors without the conflict of a mandate to protect the university’s reputation.

So the real question raised in cases like the one at UMD is whether such advocacy can exist at all at university campuses or whether student advocates will be too afraid of their legal exposure. What would student advocacy look like without the right to defend the victims those advocates claim to represent? Will students be deterred from campus advocacy when it could well threaten their own prospects and financial well-being? How might this case disrupt the pipeline of experienced activists who will later become lawyers and activists in this field?

I founded the student organization, Student Activists Against Sexual Assault (SAASA), at Temple University my freshman year. As a chapter of the national organization It’s On Us, my aim was simple: to support and uplift student survivors through their trauma, healing, and—should they decide to report—to lend assistance over the course of a Title IX investigation. Our organization has become a crucial forum for survivors to speak out. We host biweekly meetings for survivors to critique campus policies, share their own experiences, and plan events like the Clothesline Project, where students can write their stories on a T-shirt and hang it on a clothesline as part of a campus demonstration, or Take Back the Night, where students can approach a microphone and share their traumatic experiences in a safe, closed-door setting.

The Connecticut and Maryland cases jeopardize the ability of my group to do this work. In my time at SAASA, I have encountered scores of survivors who have experienced all sorts of institutional obstacles to getting their voices heard and their complaints taken seriously. When multiple victims stepped forward alleging that Temple’s assistant football coach was misusing the dog-sitting app Rover to spy on the women who took care of his dog with hidden cameras around his house—including ones in his bedroom and bathroom—our organization issued a statement denouncing his actions as well as our university’s lack of transparency in handling the victims’ statements. We sat in on safety roundtables with our student government and campus leadership, fought for increased transparency, and demanded that the school reprimand and discharge the coach following an appropriate investigation.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →That’s but one recent example of the critical advocacy that SAASA provides in the ongoing struggle for gender justice and equity—and to ensure that campuses no longer serve as hunting grounds for sexual predators and assailants. Now, however, we may see our viable zone of advocacy on campus disappear. If advocates and administrators are perennially looking over their shoulders for a possible defamation action in the making, groups like SAASA will find it difficult, sometimes impossible, to do their work.

We are seeing a similar insidious strategy play out as we move into a new era of restricted reproductive freedom and bodily autonomy in the wake of the 2022 reversal of Roe v. Wade. This summer, a young Nebraskan woman was sentenced to 90 days in jail for aborting her fetus. Here’s the parallel: Her mother was also charged with several felony counts based on her efforts to assist her. The mother’s sentencing date is set for mid-September, and she will almost certainly face incarceration. Those who support women as they seek autonomy and bodily integrity are being increasingly targeted.

Campus speech and advocacy on these issues are under threat at a moment when they’re urgently needed. Instead of creating a legal system that protects bodily autonomy, the courts could soon create legal repercussions for defending assailants and advocating against campus sexual assault.

More from The Nation

Facing Legal Threats, Colleges Back Off From Race-Based Programs Facing Legal Threats, Colleges Back Off From Race-Based Programs

College programs designed to give students from underrepresented groups a foothold in careers are being reframed or disappearing.

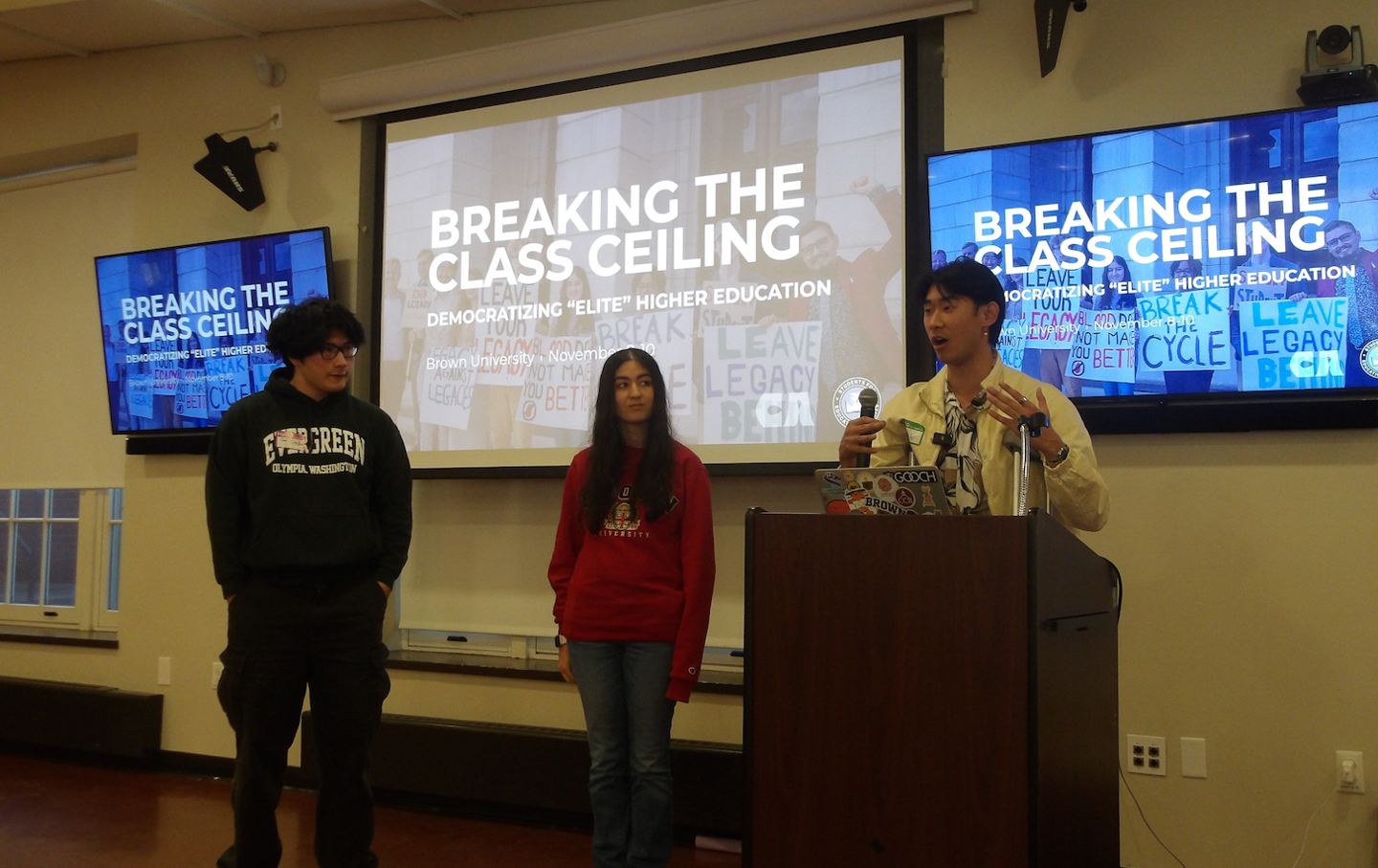

The Elite College Students Fighting to End Legacy Admissions The Elite College Students Fighting to End Legacy Admissions

In November, organizers at more than 18 universities met for a conference with Class Action to discuss how to democratize higher education.

Here in Iowa, the Fight Goes On Here in Iowa, the Fight Goes On

In Johnson County, a record-breaking 87,012 people voted on Tuesday. Democrat Christina Bohannan beat the Republican incumbent by over 35,000 votes—just 800 shy of what she needed...

How Cornell University Is Quietly Quelling Gaza Dissent on Campus How Cornell University Is Quietly Quelling Gaza Dissent on Campus

The university has emboldened its Office of Student Conduct and Community Standards to ban pro-Palestine protesters from campus “to protect the university community.”

Good Luck Finding Legal Representation if You Support Palestine Good Luck Finding Legal Representation if You Support Palestine

A law firm dumped me as a client because of my support of students’ right to protest Israel’s actions. I’m far from the only one shut out.

The Politics of Speech on the American Campus The Politics of Speech on the American Campus

Freedom of speech on campuses has long been under attack, but now more than ever.