“We Have Covered Events No Human Can Bear”

Journalists in Gaza have bartered their lives to tell a truth that much of the world still doesn’t want to hear.

Relatives and colleagues bid farewell to Palestinian journalists Abdel Raouf Shaath, Mohammed Qashta, and Anas Ghoneim, who were killed in an Israeli airstrike.

(Abed Rahim Khatib / Picture Alliance via Getty Images)

This piece is part of A Day for Gaza, an initiative in which The Nation has turned over its website exclusively to voices from the Gaza Strip. You can find all of the work in the series here.

Can you fathom what it means to be a journalist in Gaza? To go months without holding your children simply because their proximity to you may get them killed?

Before the war began, I worked as an English-language correspondent in Gaza. I sought out mostly stories of success: The ambition that glittered in the eyes of our children, the enduring cultural traditions of the Strip and its landmarks. We were a people worn down by the scarcity of choice. But we were intent on survival, willed toward a better future, souls nourished by hope and by love.

Then, overnight, in October 2023, I was pushed to become a war correspondent. Some of my first reports came from the inside of the emergency room at Al-Shifa Hospital, where I encountered an endless procession of victims. I shuddered through the sound of bombardment and fire belts, shook at the sight of a charred child, a wounded woman, a mutilated boy.

A Day for Gaza

-

A Ceasefire in Name Only

-

The Gaza Street That Refuses to Die

-

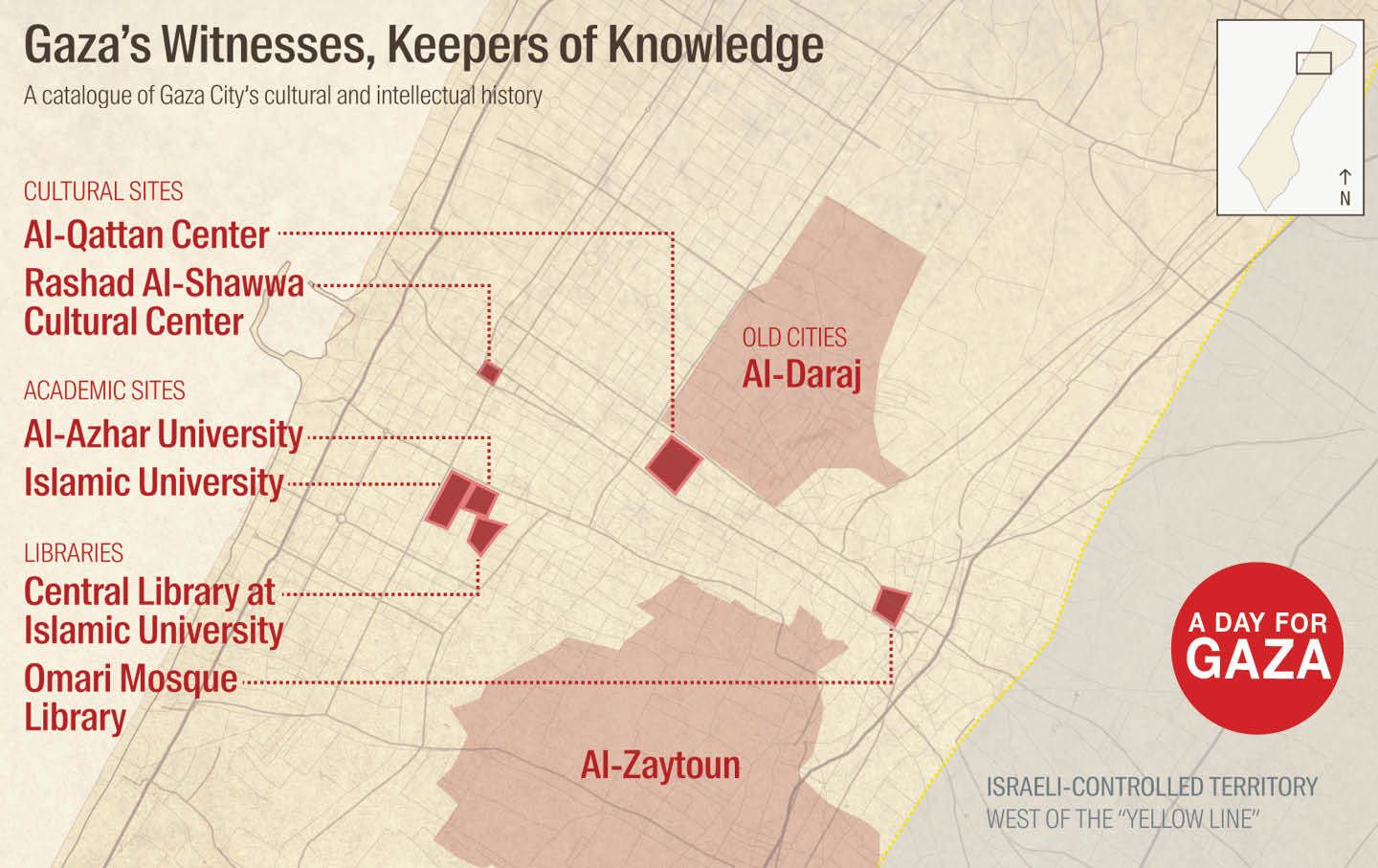

A Catalog of Gaza’s Loss

-

My Sister’s Death Still Echoes Inside Me

-

What Gaza’s Photographers Have Seen

-

How to Survive in a House Without Walls

-

What Edward Said Teaches Us About Gaza

-

What Happens to the Educators When the Schools Have Been Destroyed?

-

At the Doorstep of Tomorrow

-

“We Have Covered Events No Human Can Bear”

Not long after, the military declared that the north of Gaza had been made into a military zone—and I was forced to make a decision. A car was prepared to take me south where I could continue to report more formally, protected by the purported safety of my press vest and my profession. This would mean leaving behind my home and family indefinitely, their fate wholly unpredictable. But there was another option. I could stay, stand before a camera without any protection, and explain to the world what was happening to us. I told them I wouldn’t leave.

Let me tell you something I’ve never admitted: I knew, in that moment, that the world would betray us. I knew that everything that had come and everything that was yet to come would not be enough to move the people of the world. My heart writhes in pain over what I endured in the north. And yet here I am, after all these long months, still pleading with the world, still proclaiming my belief in your humanity.

Since the beginning of the genocide, Israel has consistently targeted journalists. It has destroyed our images, strangled our voices, and uprooted our words. These transgressions against Palestinian journalists have only one purpose: to allow Israel to carry out its plans in the darkness, granting its military free rein to commit whatever bloody atrocity it desires.

Each of the 245 journalists killed by Israel had a life, a family, a dream, ambitions. Some were waiting for the birth of their child, others were killed having barely known their newborn. My friend, Yahya Sobeih, was murdered hours after he spent an afternoon handing out sweets in celebration of his daughter’s birth. Mohammed Salameh had plans to marry his fiancée, Hala, only days after he was murdered. Death swallows us whole here. One after the other, our colleagues and friends fall like leaves in autumn.

Recall the morning of August 25, 2025: The Israeli army bombed the Nasser Medical Complex. Two strikes in sequence: a “double-tap.” The first claimed the lives of the journalists, civilians, and doctors who had sheltered in the hospital. The second strike anticipated the arrival of rescue teams and other journalists who had hurried towards the site. It was a coordinated crime that unfolded live before the eyes of the world. Twenty civilians were murdered and countless more were wounded—among them, five of my colleagues, including my friend Mohammed Salameh.

How can this world live with the reality that there exists an entire people whose hospitals are continuously bombed—hospitals that are overflowing with doctors, patients, with those who have been forced to seek refuge inside its walls? Hospitals that hold journalists who have been forced there to document, moment by moment, the realities of brutal, dirty, greedy war? Have our souls really become so cheap?

Shortly after the TV channel, Al-Ghad, liv-streamed the second strike on the Nasser Medical Complex, its Gaza correspondent, Ibrahim Qanan, went to Instagram to explain the predictability of these sort of attacks. “Israel possesses highly precise weaponry,” he wrote. “They knew, without a doubt, that members of the Civil Defense were present in the building when it was struck. But, as they see it, there is nobody standing in their way. Israel commits war crimes on a live broadcast simply because they understand that there is nobody in the international community who is willing to confront them.”

Journalism is supposed to be the fourth estate. The safety of its practitioners is considered sacred, even during times of war or conflict. But in Gaza, journalists have been offered no protection. Instead, they’ve been left to die as they broadcast their daily pleas.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Our practice has not fundamentally changed since the ceasefire. We journalists continue to report under immense pressure, enduring the psychological strain brought on by repeated military attacks. Our psyches are now more familiar with war than with peace.

Here’s how Abdullah Miqdad, Gaza’s correspondent for Al Araby TV, has described our present condition:

“The constant psychological fear for a journalist is that escalation and war could return at any moment. Journalistic life cannot go back to what it was before the war. The nature of coverage has changed. It now encompasses all the catastrophic consequences the war has left behind, expanding how daily life itself is reported and examined.”

Amid this precarity, we continue to offer our bodies as proof that the danger we face is real. So many of us have lost family members. Some of us carry those shrouds with us everyday. Others have already penned our wills, anticipating our death at any moment. At night, we forgo sleep for the company of murder and destruction; we will ourselves towards danger. Atop the rubble, we share images of charred bodies, wading through flesh and the smell of blood.

This is not heroic: We persist because there is no alternative. We have surrendered even the safety of our own families in order to protect the truth.

“Two years of war have left a permanent mark,” the journalist Ibrahim al-Khalili told me, “We have covered events no human can bear.”

How can a person return to normalcy after witnessing every intimate detail of this genocide? What might heal such a soul?

Perhaps the greatest lesson we have learned bartering with our lives is that the world is truly unconvinced by our words, unmoved by our images.

Even after all this time, many international news agencies continue to treat our work as if it were unreliable, as if we are witnesses unworthy of believing. The truth of our own murder, our own annihilation, can only be verified if told through a voice that parachutes into our desecrated Strip. Our words, drenched in blood, are insufficient; only foreign journalists can truly tell our story.

In the thrum of this hypocrisy, seeking to minimize their fiscal liability, most international news agencies have turned to another kind of exploitation. They have replaced official employees with contractors, paid monthly or per report or image, and foregone the legal responsibility that guarantees our protection. Our bodies are sacrificed to protect institutions that don’t even believe us. If these news agencies continue to find prominence without honoring our labor and blood, then surely we are entitled to decide who narrates our story—who carries our cause, who bears our words to the world.

When one of our colleagues is martyred, a cloud of grief descends on us all, and our strength falters. We have come to know this profession as a subjugation.

There is a collective understanding among journalists in Gaza that those who have perished will not be the last, that any one of us could be next. Everyday as I report, I think of my family, of my fate. I wonder if my name will be soon added to the list of martyrs simply because I insist on writing, on recording, on sharing the realities we live through. What is being done to us is a stain on a world complicit in our annihilation. But nothing can be taken from us anymore.

Aya Jouda, a field correspondent for Tasnim News, has spent years documenting the siege on Gaza. Her persistence, she said, comes from a belief that “to witness these events is a human, ethical, and national duty.”

“Gaza is not a headline, or a statistical report. It is human lives being annihilated beneath bombardment and blockade,” she said. “Yes, when the outside world shows solidarity, it gives me hope. It’s proof that our voices can reach beyond these borders. But when that solidarity is absent, our sense of betrayal deepens and with it, our determination to keep telling the truth, no matter the dangers we face.”

Like my colleagues, I can no longer be stopped. There are days when it feels as though our lives are going to waste; our efforts are pointless, our will to persist misspent. We are sustained, however, by the fragile faith that perhaps, overnight, the world may halt this ruthless war. We await that day with the hope that our lives may one day be lived as they ought to be: in love and in peace.

Your support makes stories like this possible

From Minneapolis to Venezuela, from Gaza to Washington, DC, this is a time of staggering chaos, cruelty, and violence.

Unlike other publications that parrot the views of authoritarians, billionaires, and corporations, The Nation publishes stories that hold the powerful to account and center the communities too often denied a voice in the national media—stories like the one you’ve just read.

Each day, our journalism cuts through lies and distortions, contextualizes the developments reshaping politics around the globe, and advances progressive ideas that oxygenate our movements and instigate change in the halls of power.

This independent journalism is only possible with the support of our readers. If you want to see more urgent coverage like this, please donate to The Nation today.