Riotous Company

Thomas Pynchon’s America

The Riotous Worlds of Thomas Pynchon

From “The Crying Lot of 49” to his latest noirs, the American novelist has always proceeded along a track strangely parallel to our own.

If God had a personality, what would it be like? The two most obvious answers—God is benevolent and merciful; God is wrathful and jealous—are plainly in contradiction with one another. To discuss the question further would mean entering into theology; the point here is only to take a stab at the character of the most God-like of American novelists, Thomas Pynchon.

Books in review

Shadow Ticket

Buy this bookAcross seven decades and, now, nine novels, Pynchon has exhibited so great an ability to create the world—to describe it in all its historical and geographical variety, as well as to supplement it with imaginary extras, like time travel and teleportation—that it appears the gift of some omnipotent deity. A second God-like trait is at once more mysterious and banal: We simply don’t know what Pynchon looks like, apart from a few photos of a bucktoothed student and Navy seaman of the 1950s. Otherwise, this exceptionally famous writer has refused to be photographed. It was probably with Pynchon in mind that Don DeLillo had his reclusive novelist Bill Gray, in Mao II, say: “When a writer doesn’t show his face, he becomes a local symptom of God’s famous reluctance to appear.”

In Pynchon’s case, God’s personality is split most evidently between the somber and the silly—gravity and its rainbow, as it were. His undeniably serious books take as their subjects such heavy historical matters as the Blitz and, indirectly, German colonialism (Gravity’s Rainbow itself); chattel slavery, the dispossession of Indigenous peoples, and intimations of a future civil war in prerevolutionary North America (Mason & Dixon); and the consolidation of industrial capitalism, including the bloody repression of organized labor, in the late-19th-century United States (Against the Day). At the same time, these epic works of historical fiction, the shortest of them some 700 pages long, also behave like indefatigable excursions into light opera: The for-the-most-part heartlessly two-dimensional characters all have silly names (say Scorpia Mossmoon, who hardly matters in Gravity’s Rainbow, or the Reverend Wicks Cherrycoke, who basically narrates Mason & Dixon), and when these cartoonish personages are not busy working for outfits that themselves boast risible titles (like ACHTUNG—the Allied Clearing House, Technical Units, in Northern Germany—from Gravity’s Rainbow, or SMEGMA, the Semi-Military Entity Greater Milwaukee Area, from Shadow Ticket, the new novel), they are often bursting into song and/or making bad puns. Altogether, it’s as if Our Father in Heaven were mainly interested in His creation as an occasion for Dad jokes.

Pynchon’s characteristic combination of tonal high spirits and doomward subject matter can be suggested by an offhandedly magisterial passage from Against the Day in which the Chums of Chance, a riotous company of turn-of-the-century dirigibilists, notice that the hot air and joyous songs that propel them over the Western steppe by no means forestall a less merry scene below:

From this height it was as if the Chums, who, on adventures past, had often witnessed the vast herds of cattle adrift in ever-changing cloudlike patterns across the Western plains, here saw that unshaped freedom being rationalized only into movement in straight lines and right angles and a progressive reduction of choices, until the final turn through the final gate that led to the killing floor.

It’s as if this inveterate maker of smutty jokes had also read Max Weber, or Jason Moore, on the fatal rationalization of earthly nature attendant upon capitalist modernization.

Another division bisecting Pynchon’s output has to do with genre. The sweeping magical-historical picaresques on which his reputation rests, all of them narrated from an omniscient point of view, were published between 1961 and 2006. Since then, Pynchon has published not simply lighter works, a category that would include the brief bad trip of The Crying of Lot 49, from 1966, or the great hippie fantasia Vineland from 1990. The generic difference marking out post–Great Recession Pynchon from the earlier stuff is more specific. Over the past 15 years, he has turned to the detective novel, in which events are recorded and (non-)revelations registered from the restricted POV of some put-upon private investigator. In his 2009 Inherent Vice, the hapless good-hearted gumshoe is Doc Sportello, a stoner probing the mysteries of post–Manson LA. (Speaking of theology, Doc spots a dude “wearing a T-shirt with the familiar detail from Michelangelo’s fresco The Creation of Adam, in which God is extending his hand to Adam’s and they’re just about to touch—except in this version God is passing a lit joint.”) In Bleeding Edge, from 2013, it’s the brash and kind fraud investigator Maxine Tarnow—“Tail ’Em and Nail ’Em,” she calls her agency—who gets sucked into inspecting the deadly financial irregularities of a Silicon Alley start-up run by one Gabriel Ice, roughly between the dot-com bust and 9/11.

Pynchon’s latest novel, Shadow Ticket, is another unraveling sleuth’s tale, an expedition into the dark potentialities of the 1930s undertaken by a good-natured lug and former strikebreaker by the name of Hicks McTaggart, an employee of the Unamalgamated Ops detective agency of Milwaukee, presently in search of the fugitive heiress to a cheesemonger’s empire. No spoiler alert is necessary in saying that you won’t likely read a punchier account of the rise of classical fascism. Besides, are spoilers even possible with Pynchon? Oedipa Maas, our heroine in The Crying of Lot 49, experiences “a hieroglyphic sense of concealed meaning” and, later, a sensation as though “there were revelation in progress all around her”—without these intimations ever delivering themselves into any definitive disclosure. This sets the pattern of Pynchon’s at once teasing and exhaustive novels, including Shadow Ticket. As one of McTaggart’s informants—the soda jerk and Prohibition-skirting booze-runner Hoagie Hivnak, if you must know—says: “You’re the private investigator, laughing boy. Go investigate.”

As I was reading and rereading Pynchon’s oeuvre for this review, I also took in Fredric Jameson’s brief book Raymond Chandler: The Detections of Totality and felt a pang of envy when this arch-theoretical critic dismisses the plots of Chandler’s classic detective novels as “notoriously incomprehensible.”

I would very much like to say the same of Pynchon’s plots and leave it at that, going on then, more comfortably, to discuss the unrepresentability of social totality under capitalism. After all, if you put a gun to my head and ask me what the crime syndicates hashslingrz, in Bleeding Edge, or the Golden Fang, in Inherent Vice, are up to exactly besides being, respectively, some homicidal cybersecurity firm and some consortium of crooked dentists—well, I’m afraid that’s my brains on the wall. But a book reviewer, like a PI, is a menial creature who must do his job.

The story of Shadow Ticket itself can be easily enough delineated, if not quite the spreading dimensions of its shadow. A ticket is investigative slang for a job, a gig—Maxine Tarnow in Bleeding Edge fantasizes a future day when her low-rent outfit might deal “only with class tickets”—and the ticket here, for Hicks McTaggart, is that his boss at U-Ops would like him to go and have a look-see for the vanished Daphne Airmont, legatee to the fortune of the equally absconded pater—or cheddar—familias Bruno Airmont, founder of an Upper Midwestern dairy dynasty. Keep your daughters close, dear readers, cuz it seems Daphne has taken up with a jazz clarinetist.

Little could be more Chandler-like than an unenthusiastic commission to chase an AWOL upper-class dame with questionable taste in men: “Mrs. Airmont would like her daughter back,” as a lawyer puts it, “with as little public attention as possible, and without the clarinet player.” The latter is a musician seemingly of Jewish descent (his swing band is called the Klezmopolitans, and he refuses to play “Nazi joints”) by the name of Hop Wingdale, whose European booking agent is alive—as Pynchon is too—to the political overtones of even the most joyous music: “So each number you play to what could turn out to be a houseful of violent Jew-haters, gambling on their collective tin ear, you’ll need to calibrate how klezmeratic, not to mention how Negro, you can afford to present yourself as.” As always, the lightness of Pynchon can be felt in his capering manner and the darkness in his subject matter, here the ascent of fascism in the Central Europe of 1932–33, to which, it turns out, Daphne has run away with Mr. Wingdale.

Not that the connection between Hicks and his investigatee is merely contractual. See, once upon a time, Hicks saved a wayward teenage Daphne from a mobbed-up North Shore den of iniquity and deposited her for safekeeping at a Chippewa reservation—more precisely (if also very mysteriously, because this is Pynchon), “a secret Indian reservation, mentioned only once in a rider to a phantom treaty kept in a deep vault under a distant mountain belonging to the U.S. Interior Department and unrevealed even to those guarding it.” Hicks bristles at the idea, expressed by several characters, that through having rescued Daphne, he became responsible for her life, but in the words of a hatmaker and Ojibwe sage who remonstrates with him: “Fact remains that once you put so much as a toe into the flow that is the life journey of another…” (ellipsis Pynchon’s).

Much of Pynchon’s novelistic method is to potentiate the psychedelic truisms and paranoid apprehensions of the 1960s—e.g., it’s all connected, man; or, there’s something happening here, what it is ain’t exactly clear—into complex narrative machinery, and this is also the case in Shadow Ticket.

Early on, Hicks complains about his quest for the heiress absconditus: “Lot of fun for somebody, too bad that matrimonials, as you’ll recall, were never my line.” The trouble is, as Pynchon relates, “Private eyes of the 1930s are emerging from an era of labor unrest and entering one of spousal infidelity.” Once serving capitalists as their hired guns, Depression-era detective agencies now find most of their business in chasing after unfaithful partners—a complaint in which it’s perhaps possible to detect Pynchon’s own preference for political subjects over the more usual romantic and sexual preoccupations of the American novel.

At any rate, Hicks needn’t have worried that hunting down Daphne Airmont would prove a strictly household gig. Another Pynchonian precept is that things are never what they seem, and it emerges that a second party, dubiously presenting itself as the nascent FBI, would like to supplement Hicks’s ostensible investigation with a more tenebrous affair, about which he will be told only what he needs to know. “Sounds like out-of-town work,” Hicks observes, to which comes the reply: “Oh, quite far out of town in fact.”

Next thing he knows (a favorite Pynchonian transition), Hicks finds himself aboard the ship Stupendica, crossing the Atlantic to Europe and thence to Hungary, one of the last-known whereabouts of Daphne and Hop. True to the form of Pynchon’s detective novels, the narrow remit of the initial case ultimately casts a broad geopolitical shadow. So it is that a coke-addled Viennese cop named Egon Praediger, who may be no more (or less) of a true policeman than his supposed FBI colleagues, tells Hicks that his secondary employers are more interested in Bruno Airmont than in his daughter Daphne. Bruno, the onetime American “Al Capone of cheese,” turns out to be caught up in something called the International Cheese Syndicate, or InChSyn. Cheese fraud naturally constitutes a serious problem for the belligerent turophiles of France, Italy, etc., but the political implications of cheese don’t meet their rind even there: “Cheese Fraud being a metaphor of course,” Herr Praediger explains, “a screen, a front for something more geopolitical, some grand face-off between the cheese-based or colonialist powers, basically northwest Europe, and the vast teeming cheeselessness of Asia.”

Never mind the paneer erasure—such intimations of global war and decolonization aren’t really cashed out in the antic story Pynchon unspools. Much of the political suggestiveness of Shadow Ticket depends instead upon the reader’s knowledge of the bleak world that lies on the other side of the early ’30s. As Hop Wingdale’s booking agent, Nigel Trevelyan, grimly warns him: “We’re in for some dark ages, kid. Dim at least. This could turn out to be thousands, maybe tens of thousands of lives.” Of course, the dire presentiment is off by a few orders of magnitude.

In the end, Hicks does track down, and incidentally sleep with, Daphne. In keeping with Pynchon’s countercultural orientation, their coupling has a cheerful casualness about it: Hicks refers to “some kidding around.” Much more emotionally and narratively significant is Daphne’s eventual reunion with her father, outside of Hicks’s presence, in Fiume, Italy. There, before going on the lam once again, Bruno Airmont hands over to her the number to a secret account in Geneva containing neither money nor cheese but, as he says, “information”: “Enough on the secret history of the InChSyn, and the full membership, anonymous and otherwise, to send the whole business up in one giant fondoozical cataclysm.” In other words, the conclusion of this tale of dairy-bolical conspiracy is to assert that the real solution to the mystery lies ahead of us still. As before in Pynchon, the story closes on a preliminary note.

Beneath the complex architecture of Pynchon’s plot proliferate the sort of glorious details that might keep one visiting Gothic cathedrals or ruined abbeys even without believing in God. Nearly everyone in Shadow Ticket gets to speak a more or less period patois bristling with fun slang: a $10 bill is a sawbuck; a gun is a heater; a bar is a speak; an attractive woman is a tomato; her legs are pins; and all of this and more is jake—that is, OK—with me.

Pynchon’s polymathic knowledge is also fun (we learn, for example, that Milwaukee is the birthplace of the QWERTY keyboard), as is his characters’ frequent ignorance: Hicks’s fellow detective Lew Basnight understands high-class types to savor “oat cuisine.” Nor is all the wordplay so innocent: “Der Führer is der future, Hicks,” our hero’s Reich-curious uncle assures him.

At the same time, Pynchon’s encyclopedia of the real and imaginary world also contains its blank pages. Much of the transportation in Shadow Ticket occurs, counterfactually, by way of autogyro—a sort of personal helicopter—and too often it’s as if the narrative itself, after leaving Wisconsin, is only skimming the surface of Mitteleuropa. In Budapest, Hicks sits in the sidecar of a motorcycle “speeding over cobbles and under arches, flying, it seems, above broken road surfaces and up impossible grades, through gateways, down indoor-outdoor corridors that seem too narrow for a bike let alone a combination.” Such hurried vagueness, here and elsewhere in Shadow Ticket, is very far from a Blitz-menaced London in Gravity’s Rainbow so richly detailed that it was difficult not to feel that Pynchon, born in 1937 in New York State, was not somehow himself a survivor of the German barrage.

What, then, is the nature of the Pynchonian detective novel, of which we now have at least three examples? The basic model clearly derives from Chandler. Here, too, the protagonist is a wisecracking shamus with a sarcastic wit, male or, in Bleeding Edge, female. And in Shadow Ticket, at least, our sardonic hero also sports, like Chandler’s Philip Marlowe, a sizable frame and is catnip to women; Hicks’s main squeeze thinks of him as “a big ape with a light touch.” (Maxine in Bleeding Edge is also pretty much a free-love type.)

In spite of his or her cynicism, the Pynchonian private dick is, also like Marlowe, a moral being, reluctant to mete out the sort of physical violence with which he or she is surrounded. Chandler’s indelible character kills only one heavy across five novels. And Hicks McTaggart in Shadow Ticket is even more strongly defined by his aversion to murder. Having come close to icing a “four-eyed Bolshevik” during his strikebreaker days, Hicks feels enormous “relief at not having killed somebody.” He instead conceives of his job as requiring him to “absorb any violence that might arise, as if there’s some Private Dick Oath like the one doctors take, with a no-harm clause, which there isn’t.”

Much of the distinction of Chandler’s detective novels consists in the fact that, unlike their genre predecessors, they don’t represent the restoration of social order through the solution of a mystery and the fingering of a villain. The plots are too elusive and unsatisfying for that, and villains still abound after the story ends. Chandler’s books are better understood in terms of their disavowed romanticism. A rescuer of innocents in peril adheres to a personal code of honor that he is able to conceal only by way of being a cynical guy who works for wages (in the form of expenses and a retainer) and by rescuing mostly blackmailers and other crooks, even on those occasions when the missing person doesn’t turn out to have been dead before the action begins.

In Pynchon, the detective’s disguise vocation is of a different kind. On the surface, his PIs could hardly pursue careers more different from his own. Servants to one-off missions not of their own choosing, they are people simply doing their jobs without any particular political commitments or knowledge of the world. Hicks, for example, is surprised to learn that Bolshevik is a Russian rather than Polish word—and still doesn’t know what it means. But of course Pynchon’s detectives end up stumbling into investigations that correspond to Pynchon’s own excursions across just about as much of the breadth of a given historical moment as can be covered in a novel. It’s as if, in his typical generosity, he has wanted to bestow upon a set of beleaguered hirelings the same omniscient vocation in which he himself clearly delights.

Upon the immediate advent of Shadow Ticket, articles in The New Yorker and The New York Times took up the question of whether Pynchon’s mad universe in the novel had anticipated the crazy reality of the mid-2020s or, alternatively, had now been overtaken by events that rival or exceed his books for sheer craziness. To which the literary, not just journalistic, response can only be: fair enough.

American reality in the 21st century abounds with people bearing Pynchonian names, such as the whistleblower Reality Winner or the libertarian rancher Tuna McAlpine. Not to mention that a conspiracy like Pizzagate, in which right-wing paranoiacs decided on a somewhat slender evidentiary basis that the Comet Ping Pong pizzeria in Washington, DC, must be a front for a pedophilia ring, is clearly a lurid plotline out of some aborted Pynchon composition. Never mind either that the cartoonishly corrupt big spender casually disparaged by Maxine Tarnow in Bleeding Edge—“Next invoice you can be Donald Trump or whatever, OK?”—is now the president of the United States in his second term. More importantly, as Ryan Ruby brilliantly demonstrated in New Left Review, one can make a compelling case that the deeper convergences between Pynchon’s 1930s and our own time are surely intended by the author. (I had refrained from reading Ruby’s review before writing the bulk of my own and must confess to having failed to spot half the dovetailings he does.)

At the same time, however, that Pynchon’s political or public world may coincide with the world we know, his fictions have in another and crucial way always proceeded along a track strangely parallel to that of historical reality, such that they can never truly converge with or depart from our own actually existing path. On one side of his work, that is, are dire scenes and calamitous events corresponding to the well-worn grooves of history; on another side, meanwhile, are characters, actants, personages, who appear to occupy a different, more fanciful timeline. So it is that Pynchon’s imaginary people with their improbable names almost always seem to be having a good time in spite of the horrors that envelop them, joking and singing as they do. If these madcap figures are, as is so often the case, eccentrics, like the alligator-hunting Puerto Rican buddies of V. or the banana-crazed Captain Prentice of Gravity’s Rainbow, they are not neurotically eccentric in a way that corresponds with the psychic life of our own society. Their departure from reigning norms exacts no steep price in worry and doubt. And when they experience pleasure of a more ordinary kind, such as having sex or getting high or dancing (for Hicks, a great hoofer, dancing itself is “vertical whoopee”), they are rarely punished or afflicted for their indulgences—another departure from society as we know it. As for their ludicrous names, these make Pynchon’s people appear to exist outside of history rather than to be creatures on whom the past, or the prior night’s excesses, might weigh like a nightmare.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Alex Woloch, in his great study of the “character-system” of realist fiction, The One vs. the Many, notes that the realist novel “has always been praised for two contradictory generic achievements: depth psychology and social expansiveness, depicting the interior life of a singular consciousness and casting a wide narrative gaze over a complex social universe.” But in Pynchon’s novels, the absence of depth psychology does not result, as in earlier periods of prose fiction, in a corresponding gain in persuasive social reality. Pynchon’s characters are sociologically diverse—in class, occupation, and geography—without giving an impression of sociological reality in their attitudes and obsessions. They are simply too unusual and having too much fun for that.

A couple of explanations might be offered for the ebullient unreality of Pynchon’s character world, bubbling alongside but never quite within the real historical developments portrayed in his books. Most obviously, one could argue that in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, novelists have found it difficult to represent anything like the true breadth of social reality for the simple reason that their personal experience no longer permits a broad enough experience of society for them to realistically convey it. But a second and different explanation, not incompatible with the first, seems to me to fit even better the character-system of Pynchon’s novels.

Earlier, we dwelled for a moment on the strikingly split personality of Pynchon’s work, in which the charnel house of modern history’s darkest episodes is visited by dramatis personae who seem to be having the time of their lives. How is it that such happy figures populate such unhappy scenes? A writer otherwise utterly unlike Pynchon, the poet Yeats, insisted in one of his greatest poems that Hamlet and Lear could never really be unhappy in spite of their tragic roles and terrible fates; the great lines they were given to speak made them happy: “Gaiety transfiguring all that dread.” Something of the same redemptive delight in language is also going on in Pynchon, whose characters don’t seem quite capable of misery so long as history affords them jokes to make, slang to sling, and songs to join. But Pynchon is not just a lover of language. He is also a decidedly utopian writer, as if in his old-fashioned American good nature and democratic love of fun, he couldn’t bear that his imaginary people should be realistically deformed and depressed by the painful world of capitalist history that they are condemned to inhabit. So, it would seem, he has populated his historical novels with joyous immigrants from some better future time, people who are not like us. Even when they work for wages, they never seem so unfree as that.

Your support makes stories like this possible

From Minneapolis to Venezuela, from Gaza to Washington, DC, this is a time of staggering chaos, cruelty, and violence.

Unlike other publications that parrot the views of authoritarians, billionaires, and corporations, The Nation publishes stories that hold the powerful to account and center the communities too often denied a voice in the national media—stories like the one you’ve just read.

Each day, our journalism cuts through lies and distortions, contextualizes the developments reshaping politics around the globe, and advances progressive ideas that oxygenate our movements and instigate change in the halls of power.

This independent journalism is only possible with the support of our readers. If you want to see more urgent coverage like this, please donate to The Nation today.

More from The Nation

How to Build a Moon Garden When the News Is All Horror How to Build a Moon Garden When the News Is All Horror

Letters From the March 2026 Issue Letters From the March 2026 Issue

Basement books… Kate Wagner replies… Reading Pirandello (online only)… Gus O’Connor replies…

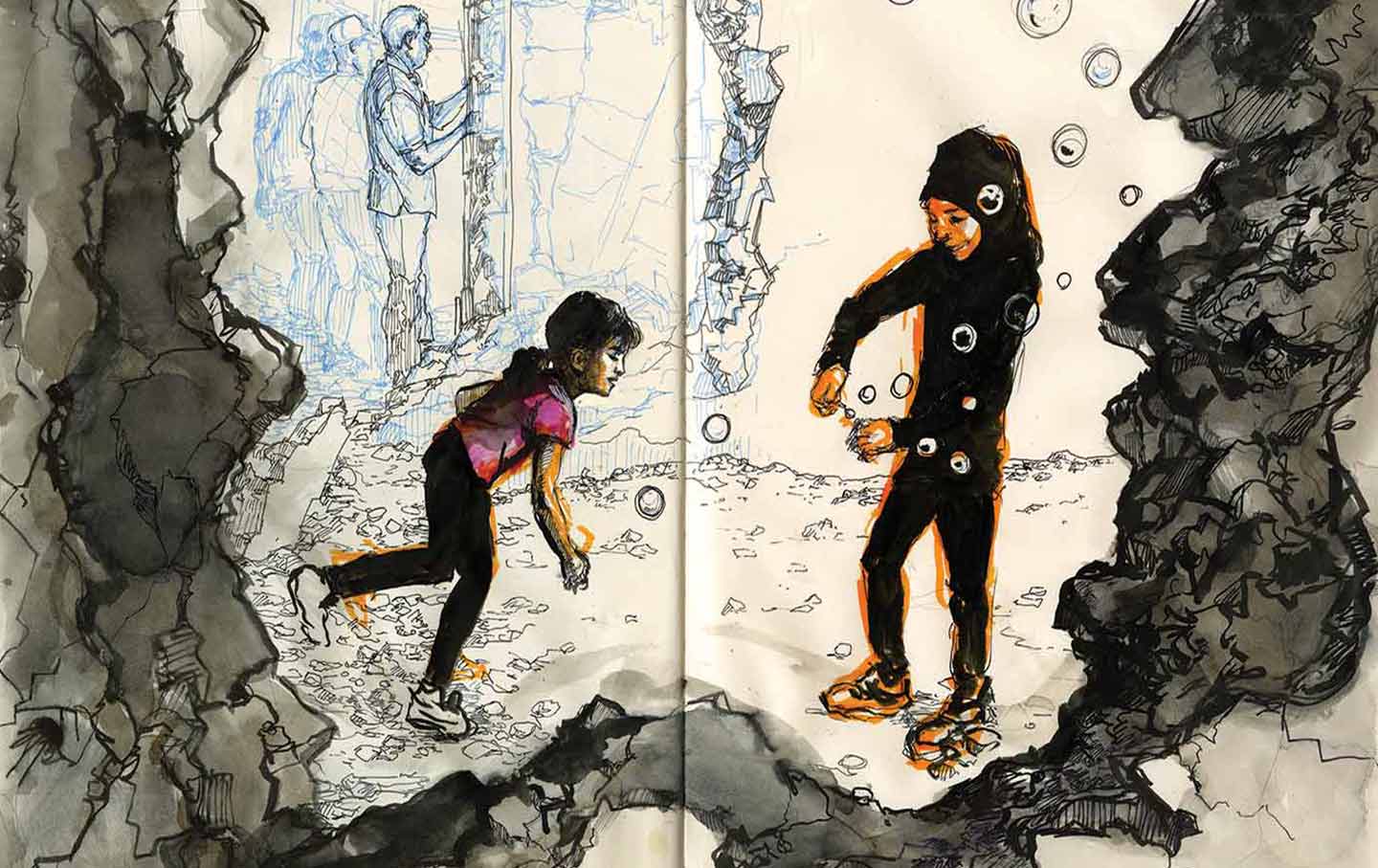

Molly Crabapple's Time Capsule of Resistance Molly Crabapple's Time Capsule of Resistance

A new set of note cards by the artist and writer documents scenes of protest in the 21st century.

The Exposure Therapy of “A Private Life” The Exposure Therapy of “A Private Life”

In her new film, Jodie Foster transforms into a therapist-detective.

Barbara Pym’s Archaic England Barbara Pym’s Archaic England

In the novelist’s work, she mocks English culture’s nostalgia, revealing what lies beneath the country’s obsession with its heritage.