The Fight for the Last Wild Salmon

In Alaska, the last stronghold for wild salmon, Native tribes and conservationists are working to save the fish from both climate change and decades of corporate greed.

Salmon swimming against the current to spawn in the streams in Alaska in August 2025.

(Hasan Akbas / Getty)On the banks of the Yukon River, after arriving by canoe only a few miles from the Canadian border, I shared some salmon with Karma Ulvi, the chief of the Native Village of Eagle in Alaska. But the fish we ate wasn’t caught locally: A plane had delivered the salmon from Bristol Bay, in the southwest corner of the state, over 1,000 miles away. For the Native tribes that have lived along the Yukon for millennia, importing is the only option. “We haven’t been able to fish for seven years,” said Ulvi.

In the last stronghold for wild salmon on earth, these tribes are fighting to save the fish. But it’s a war with many fronts, none of them simple: climate change, federal funding, competing scientific narratives, and, ultimately, corporate greed. Heat stroke during the summer has left scores of dead fish on the banks, unable to reach their spawning grounds. And over the last few decades, Alaska has seen more rain in the fall, causing floods that wash out salmon eggs. “They’re not managing for sustainability,” said Ulvi of fisheries management that allows billions of dollars of commercial fishing to take place while Native villages face malnutrition. “They’re managing for maximum profit.”

At the village’s first “culture camp,” attendees cleaned and processed fish while speaking their own language—a rare dialect of Hän Athabascan—and practiced traditional dances. First Nation tribes in Canada have been doing these camps for years, as have some Alaska villages on the Yukon, creating a place for Indigenous practices to be taught and applied.

After talking to the locals, I’d continue on to an international salmon monitoring station downriver from the village. The culture camp would last nearly a week, but similar fish camps used to last for months. During her youth, Bertha Ulvi, the chief’s mother, said that her family’s fish camp—which would have been one of a dozen in the village—could easily catch 300 salmon in a day. “All the members of the family pitched in,” said Jody Potts-Joseph, a resident of Eagle Village. “Fishing kept us busy all summer, you know.”

Potts-Joseph is a long-distance dog musher who qualified for her first Iditarod this year—the first Alaska Native woman to run the race since 1993. But instead of feeding her sled dogs a salmon a day, which she used to do, she has had to truck in extra kibble from out of town. Of course, salmon don’t just provide for humans and dogs: Hundreds of animal and plant species, depend on the salmon-driven marine nutrient cycle, including bears, conifers, and insects “It wasn’t just putting away fish for food security,” she said of the camps, “it’s also the transmission of knowledge.”

The first commercial fishery on the Yukon was set up over a century ago. When these corporations were allowed in, they harvested hundreds of thousands of salmon for export in one season, devastating the stocks. After that, commercial salmon fishing was banned for nearly a decade.

But once commercial fishing was allowed again—after airplanes became the dominant transportation in the area, alleviating some of the fishing pressure from feeding salmon to dog mushing teams—stocks faltered. In 1953, President Eisenhower declared the salmon fisheries a federal disaster.

One of the primary goals for Alaskans, achieved in 1959, was for the state to manage their own salmon stocks rather than the outside interests that were responsible for overfishing. The 1970s and ’80s saw banner years for commercial salmon fishing on the Yukon, and, while there were blips in the stocks, fisheries management was always able to recover. But when industrial trawling and climate change intensified in the ’90s, king salmon stocks began to decline once again. Since then, it has gotten much worse.

In 2024, with hopes to revive the depleting stocks, the United States and Canada signed a seven-year moratorium on fishing Yukon king salmon. But the ban wasn’t limited to commercial fishing. Though many tribes’ existence and culture rely on the fish, none of them were consulted before the full moratorium was signed.

Environmental historian Bathsheba Demuth, a professor at Brown University who is writing a biography of the Yukon River, believes we have “deep obligations” to let Indigenous people along the river make decisions for how they want to live. Yet, she explained, consulting them has not been the political norm for the last 150 years. “But that’s a choice,” Demuth said, “and not one we have to keep making.”

The health effects from a lack of local salmon have been devastating, especially in Eagle, where food is often expensive and difficult to purchase, and the absence of consistent, healthy protein is felt more acutely than it would be in other parts of the country. After the salmon collapse, Alaska Natives living along the Yukon saw a 50 percent increase in malnutrition and a 25 percent increase in diabetes, according to a report commissioned by the Tanana Chiefs Conference, a nonprofit encompassing 42 tribes from Interior Alaska, which pays more than $2 million a year to bring salmon to those that depend on it.

The report was part of a review by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, a primary managing partner of federal fisheries, that investigated the environmental impact on chum salmon—a species known for colorful stripes and big, sharp teeth that develop once they swim upriver. These reviews are required before federal management can put caps on the accidental catches from industrial fishing boats, which drag the floor of the Bering Sea for pollock with unbelievably large nets—often with an opening the size of several football fields. Other fish, like salmon, are unintentionally swept up as bycatch, left flopping, crushed, or dead.

The practice, called bottom trawling, is illegal in many fisheries around the world—and in much of Alaska too. Yet ambiguous regulations allow pollock trawlers in the Bering Sea to use these mid-water nets on the ocean floor. The trawler fleet is proud of its purported bycatch rate of 1 percent. Since each of the nets hold up to 300,000 pounds, there can be 3,000 pounds of accidental catches each time they reel the fish in. More than 100 trawlers operate in the Bering Sea fleet, and they admit to millions of pounds of bycatch each year.

By law, these boats are required to throw the bycatch overboard—which means lots of discarded salmon. In 2024, the Bering Sea trawling fleet reportedly threw 10,000 king salmon and more than 30,000 chum salmon overboard, while villages along the stretch of the Yukon River were not allowed to fish, a move seemingly at odds with the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act, which passed in 1980 and guaranteed priority fishing to rural residents over commercial interests.

In 2020, the Yukon’s chum salmon runs collapsed. That year, the chum bycatch from trawlers in the Bering Sea included more than 340,000 salmon, while those living on the Yukon caught fewer than 100,000. Federal management is expected to finally put a cap on chum bycatch early next year—aimed at trawlers in the Bering Sea—to prevent further damage to the ecosystem, a perfect example of the fisheries management’s glacial pace. In 2023, the trawl fleet accidentally caught 10 orcas. Only one was released alive.

Ulvi said that kind of waste directly conflicts with Alaska Native philosophy, which insists on respect and using all parts of a harvested animal. “It’s crazy to me. All that high-quality salmon are tossed in the ocean and we’re saving all the pollock,” said Ulvi. “We’ve been managing these rivers for thousands of years. We don’t overfish and we don’t throw back fish.”

The Yukon’s king salmon run is the longest in the world, a whopping 2,000 miles. After the salmon’s epic journey, they spawn and die—at least, when we let them. King salmon used to come in at more than 90 pounds and lived to around eight or nine years old. Now, on average, they’re closer to 30 pounds and have five-year life spans.

Though wild salmon face many problems—including warming oceans and rivers from climate change—trawling bycatch is often met with the most ire, both on the Internet and during public testimonies at management meetings. In November, federal troopers raided the offices of an Alaska trawler’s group as part of an active investigation about claims that multiple seafood processors have been illegally profiting from salmon bycatch. But it’s not just salmon affected by trawling. These ships scoop tons of halibut, crab, and herring, all of which have recently suffered stock crashes. Over the last few years, canneries across the state have closed due to uncertainty in the fisheries and widespread market price collapse.

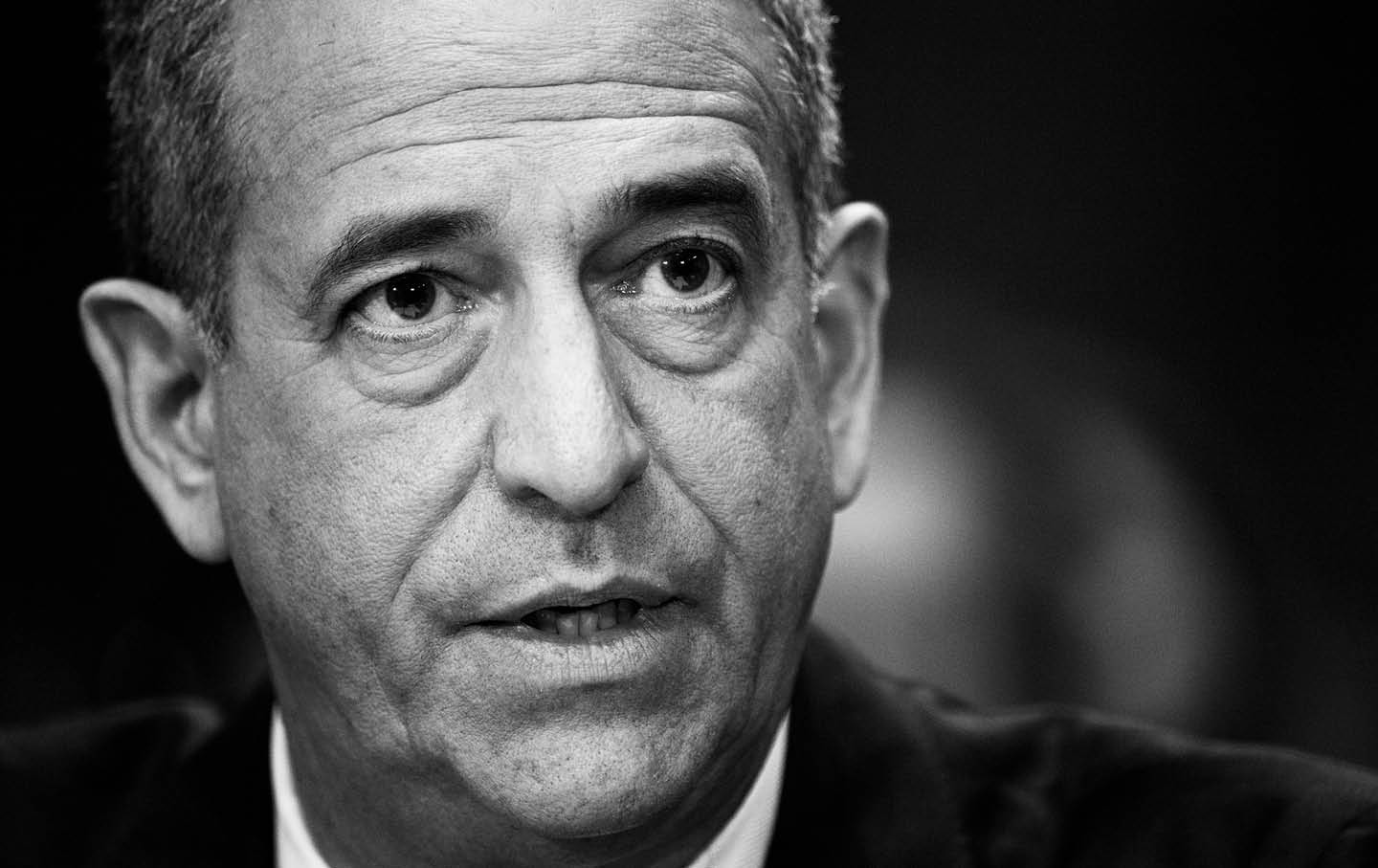

Commercial seafood hauls in Alaska make up 60 percent of the national total, and pollock—a smaller, mottled fish known for its low calories and white, flaky flesh—regularly accounts for nearly a third of the harvest. In 2023, industrial trawlers caught nearly 2.5 billion pounds of the fish, most commonly consumed in fast-food restaurants and frozen meals, typically processed in China. Pollock is the priority of the US Commerce Department, which oversees NOAA. In September, NOAA administrator Eugenio Piñeiro Soler and Alaska’s US Senators Dan Sullivan and Lisa Murkowski delivered speeches at the pollock fisherman conference in Seattle and assured them of their support. “This [year] is the second-largest USDA purchase of pollock in history, and we’re shooting for more next year,” Muskowski told the crowd.

Of course, Trump has only added more uncertainty to an already precarious salmon situation. Since taking office, Trump’s administration has cut about a quarter of the workforce from Alaska’s federal fisheries management system, and delayed funding for the North Pacific Fishery Management Council, which manages the Bering Sea trawlers. The funding came three months later than usual, according to executive director Diana Evans. “It wasn’t just that we knew it was going to be late,” said Evans. “We had no idea what amount we would actually receive.”

In early 2025, Trump signed two separate executive orders: Unleashing Alaska’s Extraordinary Resource Potential and Restoring American Seafood Competitiveness. The former paved the way for the “Ambler Road”—a proposed 211-mile passage through Native land and a national park to access deposits of copper, zinc, cobalt, and other critical minerals. The road will require thousands of culverts—circular metal tubes buried under roads to channel water—many of which salmon must pass through to arrive at their spawning grounds. The latter encourages deregulation and seeks to open up protected waters.

The administration’s cuts also included a National Science Foundation planning grant that allowed Courtney Carothers, a professor at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, to create an innovative fisheries research center informed by Indigenous knowledge, “based on respect and reciprocity between people and fish,” Dr. Carothers. She explained that a total shift in fisheries management is needed to save wild salmon, away from “the one we currently have that’s based on maximizing exploitation.”

After spending a couple days discussing fish with the Ulvis and other residents of the village, it was my turn to become part of the river. I launched a canoe into the Yukon, leaving Eagle behind. I moved swiftly downriver as golden eddies swirled and silt from the river buzzed against the hull. The river felt impossibly huge, nearly 2,000 feet wide, as I passed Bertha’s childhood fish camp, untouched for years, where brush grew thick to the shore and there were no buildings in sight.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →As I paddled onward through land gone lonesome, I spotted more fish camps going back to the woods before I came to the sonar station that the salmon treaty with Canada enabled. Quinn Davis, the station manager, stood on the shore as three Canadian women worked a net from a skiff. Bears visit there often, as several shotguns hanging around indicated. Davis gave me a tour of the camp, explaining the difference between the two sonars they used to count fish passing the station. In 2025, Davis and the other researchers tracked about 24,000 king salmon, far short of the over 70,000 aimed for in the international agreement.

Saving wild Alaska salmon isn’t just a Native endeavor; most fish conservationists in the state have been ringing the alarm. “What’s happened in the last five years is totally off the charts,” said Professor Erik Schoen of the International Arctic Research Center at University of Alaska Fairbanks, whose research on the Yukon River and its tributaries has informed state and federal fisheries management. Last summer, Schoen joined other researchers and Native advocates to publish an article specifically addressing the food security crisis on the Yukon River, with calls for better management and more use of Indigenous knowledge. “We’re used to salmon runs going up and down,” said Schoen, “but this is crazy.”

In 2024, Alaska reportedly led the world in releasing hatchery-produced salmon, topping over 2 billion fish, despite the growing evidence that hatcheries disturb the ecosystem, damaging wild stocks and increasing their likelihood of catching diseases. Though these hatcheries claim to be independent from the state, according to Virgil Umpenhour, a three-time former state Board of Fisheries member, who came to Alaska in the early 1970s after serving as a sniper in the Vietnam War. Now he sits on the local fisheries advisory board in Fairbanks. But despite the claim to independence, Umpenhour explained, hatcheries are loaned money to operate every year by the state government, which rakes in tens of millions from taxes on fish caught in Alaska waters. The state also used to provide low or no-interest loans for fishermen to buy boats that make their quota off the hatcheries’ fish.

“I have personally seen the kind of decline that never should have happened,” said Gale Vick, a fellow member of the board. They both say that state management is not following its own regulations, particularly the precautionary principle of the sustainable salmon policy, which gives priority to care for wild salmon stocks over all others. “Our collective ignorance and hubris and greed have led us here,” said Vick.

Like tributary waters gathering speed as they flow into the main river, support for Native fisheries management has moved quickly in Alaska. Last year, federal managers added three tribal seats to their board, citing their unique perspective and Alaska Native’s salmon practices as “economic, spiritual, and cultural.” Tribal organizations also signed an agreement with the federal government intending to bring more Indigenous knowledge to their Gravel to Gravel Keystone Initiative, which aims to restore Pacific salmon by rehabilitating ecosystems, improving fish passage, and conducting more collaborative research.

In May 2024, the legislature confirmed Native Village of Nenana tribal member Olivia Henaayee Irwin to the Alaska Board of Fisheries. She shows up to each meeting with stacks of color-coded, annotated regulations. Irwin intends to support Indigenous knowledge holders by connecting them with fisheries management biologists to train them in their ways, like knowing what crane migration signals for salmon runs. She also hopes to see designated seats on fisheries boards and commissions. There’s a bill working its way through the state legislature that will do just that. She also wants to further enforcement of existing regulations, like wanton waste, which align with Native values.

But merely giving Natives a seat at the table of fisheries management now, when there is a crisis, may or may not provide the requisite remedy. And, in many ways, the damage has already been done. “When my father committed suicide, I began a deeper understanding of how salmon so integrally related to our wellness as individuals,” Irwin told me. “Being unable to do what for 10,000 years our ancestors had been able to do, it’s leaving our people without purpose.”

Support independent journalism that does not fall in line

Even before February 28, the reasons for Donald Trump’s imploding approval rating were abundantly clear: untrammeled corruption and personal enrichment to the tune of billions of dollars during an affordability crisis, a foreign policy guided only by his own derelict sense of morality, and the deployment of a murderous campaign of occupation, detention, and deportation on American streets.

Now an undeclared, unauthorized, unpopular, and unconstitutional war of aggression against Iran has spread like wildfire through the region and into Europe. A new “forever war”—with an ever-increasing likelihood of American troops on the ground—may very well be upon us.

As we’ve seen over and over, this administration uses lies, misdirection, and attempts to flood the zone to justify its abuses of power at home and abroad. Just as Trump, Marco Rubio, and Pete Hegseth offer erratic and contradictory rationales for the attacks on Iran, the administration is also spreading the lie that the upcoming midterm elections are under threat from noncitizens on voter rolls. When these lies go unchecked, they become the basis for further authoritarian encroachment and war.

In these dark times, independent journalism is uniquely able to uncover the falsehoods that threaten our republic—and civilians around the world—and shine a bright light on the truth.

The Nation’s experienced team of writers, editors, and fact-checkers understands the scale of what we’re up against and the urgency with which we have to act. That’s why we’re publishing critical reporting and analysis of the war on Iran, ICE violence at home, new forms of voter suppression emerging in the courts, and much more.

But this journalism is possible only with your support.

This March, The Nation needs to raise $50,000 to ensure that we have the resources for reporting and analysis that sets the record straight and empowers people of conscience to organize. Will you donate today?

More from The Nation

Rep. Summer Lee: The Fight for Environmental Justice Is Far From Over Rep. Summer Lee: The Fight for Environmental Justice Is Far From Over

The Trump administration’s destructive environmental policies will cost us all. But we must not give up.

A World on Fire Needs More Climate Reporting—Not Less A World on Fire Needs More Climate Reporting—Not Less

War is a climate story, but billionaire media owners don’t want to tell it.

The Iran War Is Also a Climate War The Iran War Is Also a Climate War

Climate change is not a peripheral part of what we’re seeing in Iran—it’s structurally embedded in modern warfare.

The Planet-Sized Hole in Trump’s State of the Union Address The Planet-Sized Hole in Trump’s State of the Union Address

Although climate change received no attention during the president’s speech, Americans must continue to find new ways of making progress against the ongoing environmental crisis.

Japan’s New Climate Bomb—in the US Japan’s New Climate Bomb—in the US

Bloomberg Green reveals the climate costs of the US-Japan trade deal.